Major trauma

PRE-HOSPITAL ASSESSMENT AND INTERVENTION

PRELIMINARY HOSPITAL MANAGEMENT OF MULTIPLE AND SERIOUS INJURIES

Pre-hospital assessment and intervention

Assessment at the scene of a road traffic collision

Obvious injuries (e.g. traumatic amputations) are sought in the victims and their level of consciousness and mobility assessed. Trapped wounded need special treatment as they often have long extrication times and need analgesia, intravenous fluids and perhaps sedation to aid release. Trapped patients can quickly become hypothermic and hypovolaemic (see Fig. 15.1).

Pre-hospital care

Airway and breathing: The airway must be assessed and secured first, whilst ensuring the cervical spine is immobilised. If the patient can speak, assume the airway is patent, ventilation is intact and the brain adequately perfused. Agitation, however, may be a sign of hypoxia. In an unconscious or semi-conscious patient, the airway can usually be temporarily secured with a jaw thrust. If tolerated, the patient should then have two nasopharyngeal airways and a Guedel oropharyngeal airway placed to maintain airway patency. Endotracheal intubation is needed if there is inability to maintain or protect the airway or to provide adequate ventilation (Box 15.1). If this proves unattainable, a useful rescue technique is to insert a laryngeal mask (LMA), as used in general anaesthesia; this may avoid the need for a surgical airway. As a last resort, an airway can be achieved using a needle or surgical cricothyroidotomy. In all seriously injured patients, high-flow oxygen therapy (15 L/min) is mandatory.

Spine: In an unconscious patient after a high-impact collision, a cervical spine fracture should be assumed until disproved. If the patient has multiple injuries, the entire spine must be protected from secondary injury during transfer and assessment. After intubation (if needed), the spine is immobilised in a neutral position on a long spinal board. This requires a semi-rigid cervical collar, side head supports and strapping as a minimum (see Fig. 15.2).

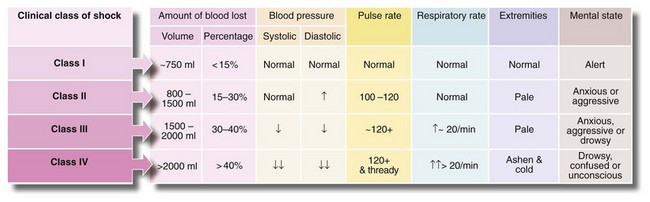

Circulation: Two large-bore intravenous cannulas should be inserted. Initial fluid resuscitation should be based upon injuries sustained and physiological parameters. More recent studies indicate that permissive hypotension is often a better strategy than the previous recommendation of rapid indiscriminate crystalloid infusion. If organ perfusion can be maintained, there are advantages in keeping the pressure low in trauma patients. Physiological compensation is effective at systolic pressures between 70 and 85 mmHg, and cerebral perfusion and urinary output are well maintained. Above this pressure, fresh clot is often dislodged (‘pop a clot’) and then bleeding recurs. A further disadvantage of unnecessary fluid resuscitation is that infusing just 750 ml of crystalloid activates cytokines and causes dilutional coagulopathy.

If a patient is unconscious without a palpable radial or pedal pulse, 250–500 ml of fluid is given immediately, followed by small boluses, repeated only until the point at which a pulse returns. This is titration by pulse and has been successfully employed in major trauma and in military campaigns. If intravenous access is unsuccessful, EZ-IO devices (Fig 15.3) are a quick way of inserting a cannula into bone marrow. Procoagulant agents such as tranexamic acid and activated factor VII are increasingly being used early to reduce blood loss following trauma. If a patient is conscious and orientated or unconscious but has a palpable radial pulse, this indicates a systolic of above 90 mmHg and fluid resuscitation is not started.

Preliminary hospital management of multiple and serious injuries

Organisation of the accident department

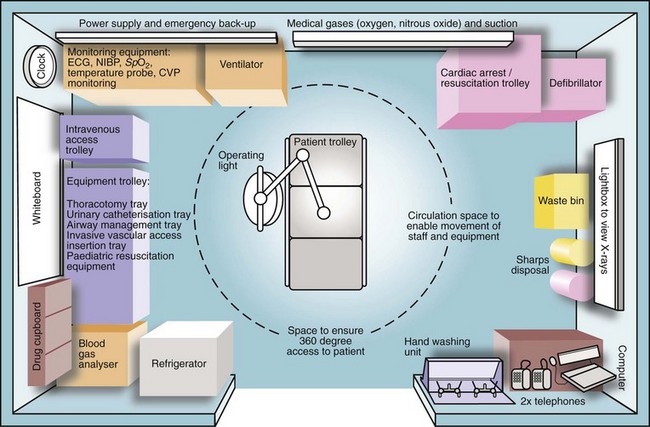

Every accident department should have a major disaster plan (Box 15.2). For any major trauma, the field team or ambulance service informs the receiving trauma unit about the impending arrival of seriously injured patients, plus an estimate of numbers and the nature and severity of injuries. This alerts the surgical and anaesthetic teams to be ready when the patients arrive (Box 15.3). Trauma units have a resuscitation room (see Fig. 15.4) with all necessary equipment so infusion sets can be prepared and drugs laid out.

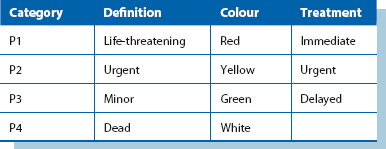

Triage is the process of sorting patients into ‘priority of treatment’ groups on arrival to enable efficient use of resources. The usual categories are shown in Table 15.1.

Initial care in the accident department

Immediate priorities after reaching hospital are:

Training has been standardised through Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) courses, originally from the American College of Surgeons and now run in many countries. ATLS principles are simple—the greatest threats to life must be treated first. Mortality at this stage following major trauma is now recognised as associated with three key pathophysiological changes termed the ‘lethal triad’ and comprising coagulopathy, hypothermia and acidosis. Damage control resuscitation has emerged as a means of directly minimising these changes, the key components of which are outlined in Box 15.4.

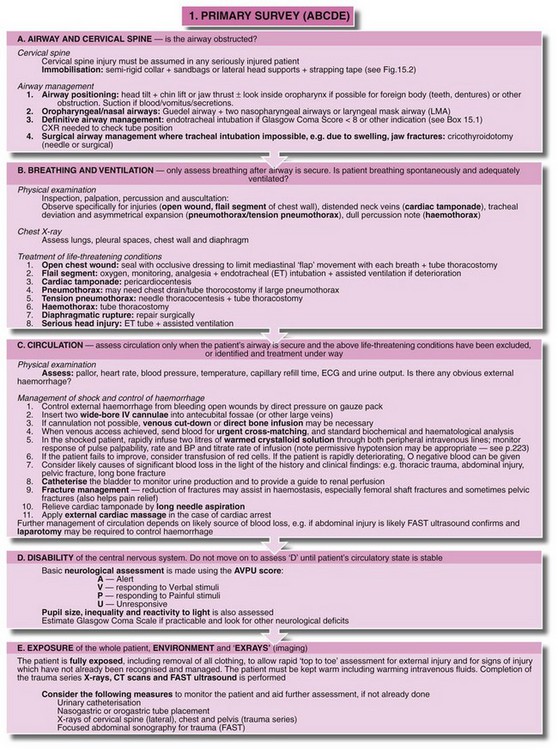

Assessment of the seriously injured patient: Despite the urgency, primary assessment must be performed systematically as soon as the patient arrives. The primary survey includes a rapid evaluation, resuscitation and crucial life-preserving treatment. Priorities are summarised in Figure 15.5. Meanwhile, regular monitoring takes place (Box 15.5).

Fig. 15.5 Primary survey and initial resuscitation

Management priorities for the patient with multiple injuries. In practice, anaesthetists usually deal with the airway and intravenous access and monitoring while surgeons evaluate the head and neck, chest, abdomen and pelvis for potential life-threatening injuries

Other elements of history come from the field team’s notes and include:

• Conscious level of patient when discovered and later changes

• Details of drugs, fluids and other treatments administered at scene

Conscious patients with suspected cervical spine injuries should be moved with extreme caution and no passive movements attempted. The patient should perform active movements; spasm or pain restricts movement in significant injury. To examine the back and perform a rectal examination, the patient should be ‘log-rolled’ by several people.

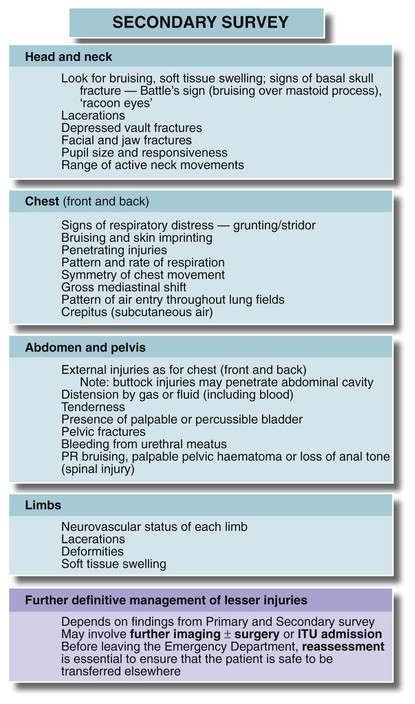

A secondary survey then assesses the potential for life-threatening problems or complications, although urgent initial treatment may delay this. The key clinical features are given in Figure 15.6; individual systems are described later. Up to 20% of multiple injury patients have injuries missed in the early stages so the secondary survey must be repeated.

Recording of events: The time of examination and the clinical findings, plus details of investigations and treatments, must be recorded in the patient’s notes, not least for medico-legal purposes.

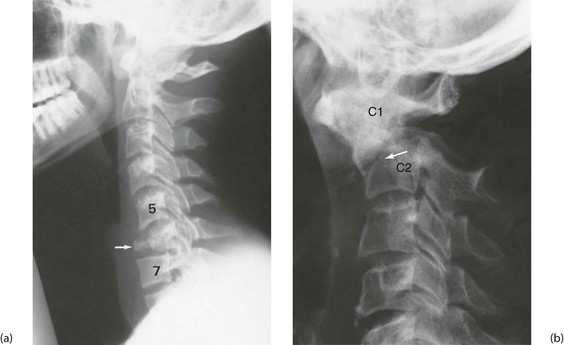

X-rays and other investigations: In major trauma, the cervical spine (see below, Fig. 15.10), chest and pelvis are X-rayed in the resuscitation room. The chest films must be good enough to exclude major chest wall, mediastinal and lung injuries and provide a baseline if the patient later deteriorates. Polytrauma patients, or patients with serious head injury should have rapid assessment and stabilisation before swift transfer for trauma CT scan. Patients should not be moved to the CT scanner until they are stable—the machine is known as the ‘donut of death’ in ATLS parlance.

Focused abdominal sonography for trauma, or FAST (see Abdominal injuries, below), is performed in the emergency department for suspected abdominal injuries and bleeding. Initial blood tests include haemoglobin and group and cross-match or antibody screen and ordering of an appropriate amount of blood. In a desperate emergency, universal donor blood (group O, Rh negative) can be transfused. Evidence from recent conflicts has demonstrated the advantages of early administration of blood products in reducing the risk of haemodilution and coagulopathy. Emergency departments are increasingly using ‘blood packs’ which include several units of packed red cells, fresh frozen plasma and platelets. These may be transfused in a 1 : 1 : 1 ratio or in a goal-directed manner, guided by coagulation testing and thromboelastography. Plasma electrolytes and glucose are measured, plus arterial blood gases if there is suspicion of respiratory failure.

Abdominal injuries

Diagnosis of abdominal injuries

Clinical observation: If surgical intervention is not needed, regular nursing observations and serial clinical examination by a doctor should be performed for signs of peritonitis or intra-abdominal bleeding. Note that significant injuries almost always become manifest within 24 hours.

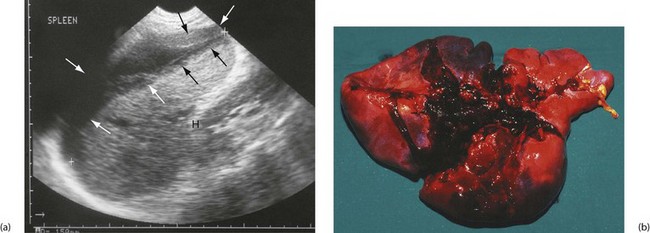

Focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST): FAST reliably detects free intra-abdominal fluid and concentrates on five areas, the ‘five Ps’—Perihepatic, Perisplenic and Pelvic in the abdomen and Pleural and Pericardial in the chest. It is, of course, user-dependent.

CT scanning for abdominal injuries: CT can identify injuries to all solid abdominal and retroperitoneal organs (liver, spleen, pancreas and kidney), bowel perforations (indirectly by detecting free gas and fluid), diaphragmatic rupture, retroperitoneal blood and pelvic and spinal fractures. This may allow conservative management of less severe splenic and liver injuries. CT is also valuable for defining the extent and configuration of complex pelvic fractures.

Penetrating abdominal wounds

Closed (blunt) abdominal injuries

Closed abdominal injuries usually result from road traffic collisions, falls, sporting contact injuries and accidents involving horses. Following substantial blunt injury, about 20% will require laparotomy. The spleen is the most vulnerable organ, especially in left-sided injuries (see Fig. 15.7). Liver injury requires greater impact force, usually from the front or right side. Pancreatic and duodenal injuries are uncommon and usually result from a heavy central abdominal impact, transsecting the pancreas or retroperitoneal duodenum across the vertebral bodies. This most commonly occurs in children falling across the handlebars of bicycles. The kidneys are vulnerable to punches or kicks in the loins.

Bowel is damaged by rapid deceleration or crushing, and is particularly vulnerable at sites where freely mobile bowel becomes attached to the retroperitoneum, i.e. at each end of the transverse colon, at the duodeno-jejunal flexure and in the ileocaecal area. A full bladder, common after a bout of heavy drinking, may rupture into the peritoneal cavity (or sometimes retroperitoneally) after abdominal impact. The bladder and urethra are also liable to be torn in displaced pelvic fractures. The clinical features and investigation of closed abdominal injuries are shown in Box 15.6.

Injuries to specific solid organs

Spleen (Fig. 15.7): The spleen is the most commonly injured organ in blunt abdominal trauma. The organ should be preserved wherever possible because of the dangers of post-splenectomy infection and sepsis. In one study, 2.4% of all post-splenectomy patients suffered sepsis and more than 50% of those were fatal.

Liver: Isolated small liver injuries may be treated by surgical repair or local resection but paradoxically, major injuries are often best treated conservatively. This is because control of deep hepatic vessels may prove impossible, particularly bleeding from hepatic veins entering the IVC. Patients with severe liver injuries should be discussed with a regional hepato-pancreatico-biliary (HPB) or liver unit. Conservative management involves large-volume blood transfusions until abdominal tamponade stops the bleeding. If operation is performed and a major liver injury is found and haemorrhage cannot be arrested, the liver should be packed with large pieces of surgical gauze, the abdomen closed and the patient stabilised. Ideally the patient should be transferred to an HPB centre as extensive liver surgery may be necessary when the packs are removed at a ‘second look’ laparotomy 24–48 hours later.

Injuries to small bowel are dealt with by simple suture or, if mesenteric vascular supply is impaired, by resection and anastomosis. Conventional treatment for right-sided colon injuries is resection and anastomosis of colon to ileum. Localised injuries to other parts of the colon without substantial faecal contamination can usually be resected and joined end to end. After knife or gunshot wounds, simple repair gives good results if there is minimal peritoneal contamination. Extensive injuries with contamination require exteriorisation of the damaged bowel ends to the abdominal wall (see Ch. 27).

Chest injuries

The types of chest injury, their clinical features and their treatment are summarised in Table 15.2.

Table 15.2

Types of chest injury and their management

| Nature of the injury | Clinical features | Treatment |

| Sternal fracture | Anterior chest pain and tenderness; ‘clicking’ on palpation; arrhythmia and ECG changes | Consider cardiac contusion or tamponade; FAST scan; 24h ECG; cardiac enzymes |

| Rib fractures | Localised pain on respiration or coughing; tenderness over fractures; usually visible on chest X-ray | Analgesia, intercostal blocks, physiotherapy, prophylactic antibiotics in chronic bronchitics |

| Flail chest, i.e. multiple rib fractures producing a mobile segment | Respiratory embarrassment; ‘paradoxical’ indrawing of the flail segment on inspiration | Intercostal block analgesia; endotracheal intubation and ventilation if hypoxic |

| Pneumothorax, i.e. air in pleural cavity causing lung collapse | Unilateral signs: loss of chest movement and breath sounds, percussion note resonant; sometimes chest wall emphysema; confirmed by chest X-ray | Intercostal drain with underwater seal |

| Sucking chest wound, i.e. open pneumothorax with mediastinum ‘flapping’ from side to side with each respiration | Gross respiratory embarrassment, audible sucking of air through chest wound | Sealing of chest wound with impermeable dressing; intercostal drainage |

| Tension pneumothorax, i.e. expanding pneumothorax causing progressive mediastinal shift to the opposite side and tracheal deviation | Signs of pneumothorax with disproportionate and increasing respiratory distress and hypoxaemia | Urgent chest drainage |

| Lung contusion | Deteriorating respiratory function; opacification of affected lung field on chest X-ray | Oxygenation, physiotherapy, mechanical ventilation if severe |

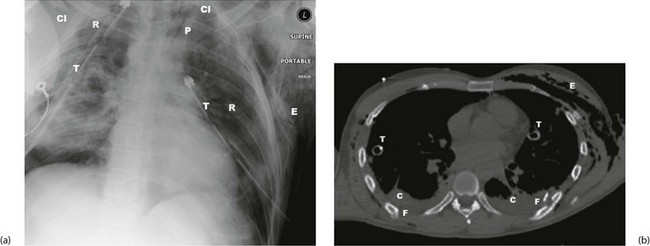

| Rupture of bronchus (uncommon) | Respiratory distress, surgical emphysema in the neck; suggested by air in mediastinum on chest X-ray (see Fig. 15.9a); confirmed by bronchoscopy | Operation by thoracic trained surgeon |

| Rupture of oesophagus (very rare) | May have surgical emphysema in neck and pneumomediastinum on CXR but diagnosis often missed until mediastinitis or empyema develops | Surgical repair if recognised early; surgical drainage and diversion if late |

| Haemothorax, i.e. blood in the pleural cavity Usually arises from chest wall injury—rib fracture, lung parenchyma or minor venous injury. Most are self-limiting. Arterial injuries less common and likely to need thoracotomy |

Dull percussion note, breath sounds absent, tachycardia and hypotension due to blood loss | Most have stopped bleeding by the time of examination and only tube drainage is required Dark, venous bleeding more likely to cease spontaneously than bright arterial bleeding Tube must be large enough to drain without clotting, ideally 32–36°F; placed in sixth intercostal space in mid-axillary line If patient haemodynamically stable, admit and observe. If continuing drainage of 200 ml+ per hour over 4 hours, should undergo thoracotomy |

| Cardiac tamponade, i.e. bleeding into pericardial cavity (usually penetrating trauma) | Hypotension, inaudible heart sounds, distended neck veins with systolic waves; enlarged, rounded heart shadow on chest X-ray; confirmed with ultrasound | Long needle aspiration via epigastric approach; operation if tamponade recurs |

| Cardiac contusion | Often arrhythmia or ECG changes similar to myocardial infarction | Conservative management |

| Rupture of aorta (usually from deceleration injury)—fatal unless false aneurysm develops in mediastinum | Back pain, hypotension; systolic murmur or signs of tamponade in some cases; characteristic widening of mediastinum on chest X-ray; diagnosis confirmed by arteriography | Urgent thoracotomy and Dacron graft or minimal-access stent graft if available |

| Rupture of diaphragm, linear split usually in left diaphragm with herniation of gut into chest (penetrating or abdominal crush injury) | Respiratory distress, bowel sounds heard in the chest; diagnosis by chest X-ray and confirmed by barium meal; many cases only discovered much later; diagnosis may be made by laparoscopy or at laparotomy | Repair of diaphragm, usually via abdominal approach |

General principles

Chest injuries are a common cause of death in patients with multiple injuries, although the death rate has fallen dramatically wherever seatbelt wearing is compulsory. Seatbelts, however, often cause typical sash pattern bruising obliquely across the chest, and minor rib and sternal fractures (Fig. 15.8). Serious chest injuries may be present without external injury, particularly tearing of mediastinal contents (aorta, bronchi and oesophagus). Diagnosis goes hand in hand with urgent resuscitation. Good-quality chest X-rays (or CT scans) are essential and usually reveal the diagnosis (see Fig. 15.9).

Thoracostomy (open and tube)

Following trauma, chest drains are usually placed in the fourth or fifth intercostal space on the mid-axillary line. The technique is shown in Figure 31.6, p. 402. Bilateral open thoracostomy is often used in pre-hospital care in ventilated patients (particularly during helicopter transfer) as a precursor to formal chest drain insertion.

Vascular trauma

Patterns of vascular injury

False aneurysm: An arterial puncture (e.g. femoral artery catheterisation or a stab wound) may cause bleeding that is enclosed by connective tissue, forming a pulsatile mass of clot known as a false aneurysm. This often presents days or weeks later. Distal flow is usually conserved and diagnosis can be confirmed by duplex Doppler ultrasound. First-line treatment is usually ultrasound-guided compression to cause thrombosis of the leak. If this fails, or for larger defects, suturing or patching may be needed.

Arteriovenous fistula: An injury to an artery and an adjacent vein can cause an arteriovenous (AV) fistula, which may eventually rupture or lead to cardiovascular compromise. These present some days or weeks after the injury. In a limb, the patient complains of a swelling with dilated superficial veins. On examination, there is a machinery-type murmur heard and diagnosis is confirmed by angiography. Treatment is by dividing the fistula and repairing the vein and artery, sometimes with a flap of fascia interposed.

Diagnosis of vascular injury

Clinical signs: Visible bleeding from a traumatic wound with signs of hypovolaemia make the diagnosis obvious. In limbs, palpable distal pulses are the most reliable sign of intact distal circulation. Hand-held Doppler probes can be misleading in detecting distal pulses and in ankle pressure measurement.

Patients with the following ‘soft’ signs of vascular injury do not require urgent investigation or exploration; they should be admitted, investigated as needed and observed over 24 hours.

Investigation: In expert hands, Duplex ultrasound can detect intimal tears, thrombosis, false aneurysms and arteriovenous fistulae, but angiography by direct puncture, CT angiography or on the operating table remains the gold standard for investigation and mapping of vascular injury. Arteriography may be needed to show the extent of injury in a stable patient with equivocal signs; to exclude injury where there are no hard signs but suspicion of vascular injury; in limb fractures with absent pulses; in injury by high-velocity missiles or multiple fragment injuries; and in blunt trauma. Angiography may be used to treat certain injuries by embolisation or stenting where expertise is available.

Management of vascular injury

Compartment syndrome: Delayed revascularisation of a limb risks compartment syndrome (see Ch. 17, p. 235). Prophylactic fasciotomy should be performed at the time of repair in these circumstances, particularly if the patient is ventilated or has an epidural, as these mask the symptoms of developing compartment syndrome.

Damage control in vascular injury

Vessel ligation: In extreme conditions, most vessels can be ligated. The common and external carotid, subclavian, axillary or internal iliac can be ligated with little consequence, but internal carotid ligation carries a 10–20% risk of stroke, and ligation of external iliac, common or superficial femoral arteries has a high risk of causing critical limb ischaemia. Coeliac axis arteries can be ligated, but not the superior mesenteric which would lead to bowel ischaemia. Almost any vein can be ligated, including the inferior vena cava (but this causes lower limb oedema).

Orthopaedic trauma

• Pain—major orthopaedic injuries are extremely painful so good analgesia and early reduction is an important part of treatment, contributing to early mobilisation and reducing the potential for deep venous thrombosis (DVT)

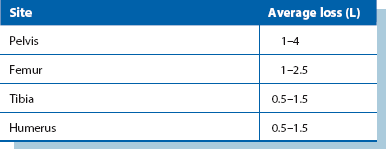

• Blood loss—internal blood loss from fractures is often substantial (see Table 15.3), particularly if there are multiple fractures, and blood volume needs to be appropriately replaced. In pelvic fractures, external fixation may reduce blood loss

• Deformity—obvious deformity should be corrected as soon as possible using temporary splinting. This treats pain and may assist vascular supply and limit blood loss

• Vascular and neurological integrity—where limbs are involved, this should be checked and appropriate investigation and intervention arranged

• Definitive fixation of fractures may be needed early or may have to be deferred until other life-threatening injuries have been dealt with

Introduction: A fracture is when there is a break in continuity of a bone. Fractures are classified so patterns of injury can be recognised, and the best treatment of any subtype agreed by consensus. Fracture patterns are linked to anatomical location, and mechanism and energy of injury. Eponymous fracture classifications are used in some countries, whereas objective systems such as the Swiss AO system (Arbeitsgemeinschaft Osteosynthesefragen) prevail elsewhere (see Box 15.7).

Fracture healing: Fractures heal by restoring bone continuity. Cancellous bone heals more quickly than cortical bone and some movement at fracture sites stimulates healing. Healing needs a good blood supply so rates of healing are more rapid in children.

Principles of fracture management: These include reduction, immobilisation and later, rehabilitation. The need for reduction depends on the fracture. Rotational, valgus or varus deformity usually needs correcting and intra-articular fractures need precise anatomical reduction. Reduction can be performed as a closed or open procedure.

Initial management of fractures: First aid minimises pain and reduces the risk of secondary damage. Broken bones are usually acutely painful and deviation causes pressure on skin and neurovascular structures. Initial treatment in the field involves assessing overlying wounds and applying dressings, reducing fractures into an immobilising splint or plaster and later, confirming the diagnosis with X-rays. These steps resuscitate the limb and soft tissues. They also reduce pain by limiting movement at the fracture site.

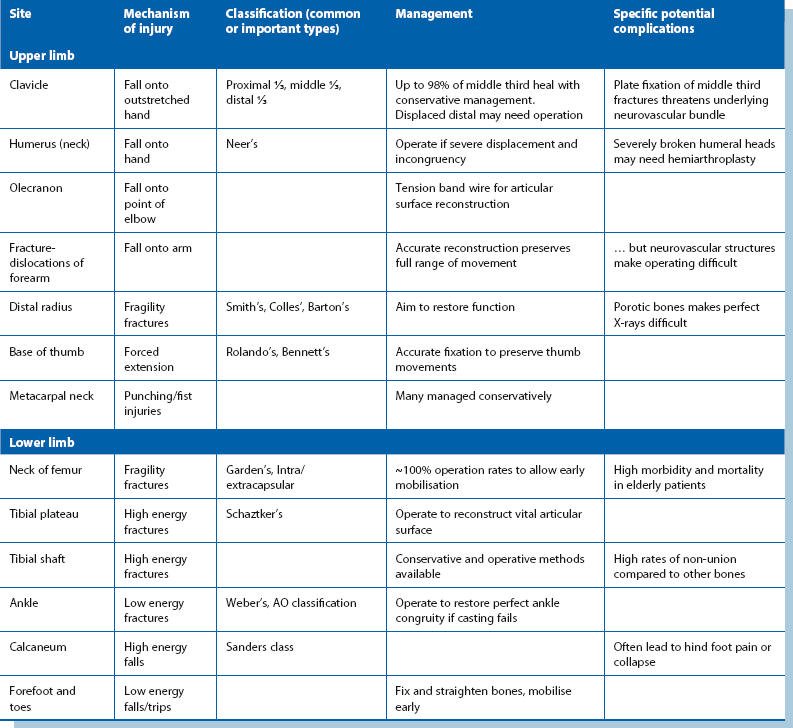

Definitive management of fractures (see Table 15.4): Fractures were able to heal long before orthopaedic surgery existed, but learning how to restore the anatomy and hold bones immobile while they healed was a major advance. Definitive management nowadays may be operative (open) or non-operative (closed). Operative treatment may not accelerate healing so the extra risks need to be justified. Complications include: infection, non-union, implant failure and refracture.

Open (compound) fractures: These must all be assumed to be contaminated. First aid treatment is the same as for closed fracture, but open fractures require early operation, ideally within 6 hours of injury. At operation the wound is cleaned, devitalised tissue is debrided and the fracture stabilised. Small clean wounds can be sutured but large or dirty wounds should be left open and closed by delayed primary suture after about 5 days.

Pathological fractures: These occur in:

• Generalised bone diseases, e.g. osteoporosis or metabolic bone diseases (osteomalacia, hyperparathyroidism, Paget’s disease)

• Localised benign bone disorders, e.g. chronic infection, solitary bone cysts, fibrous cortical defects or chondromas

• Malignant disease: metastatic cancers, myelomatosis, primary malignant bone tumours

Complications of fractures (see Box 15.8): The likelihood of complications depends on the mechanism of injury and the amount of force through the area at the moment of fracture. Sharp bone ends can perforate or crush nearby structures such as muscles, skin, blood vessels and rarely nerves; hyperextension of the knee can damage popliteal nerves. Prompt recognition and fracture reduction is crucial as fracture deformity continues to provoke inflammation and damage.

Malunion can lead later to disordered mechanical forces in the rest of the limb and back, and may cause osteoarthritis in nearby joints. Displaced intra-articular fractures with an irregular joint surface markedly increases friction, leading to post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Delayed union leads to long periods of disuse, and the entire limb can suffer from muscle atrophy, osteoporosis and joint contractures if not treated early. For Compartment syndrome, see Chapter 17, p. 235.

Specific fractures

Common upper limb fractures: The most common and their usual management are:

• Metacarpal neck—often left to heal in mildly angulated position

• Base of thumb metacarpal—fragments accurately reduced and fixed

• Distal radius—deformity reduced and fixed, e.g. Colles type

• Olecranon process—articular process reconstructed and fixed

These fractures each have typical patterns of presentation. For example, distal radius fractures are often in bone weakened by osteoporosis, and a simple fall from standing can cause an angulated and deforming fracture needing surgery. Conversely, entirely normal bone in the metacarpal neck can be fractured in young adults fighting with fists.

Common lower limb fractures: The most common lower limb fractures are:

Fragility fractures due to osteoporosis far outnumber the others and affect a large number of older patients. Femoral neck fracture still carries a high mortality. Operative treatment carries risks but is still the best method of restoring mobility and preventing death from other causes. Nevertheless death rates of 10–30% at 1 year are common.

Pelvic fractures: The pelvis is a strong structure and very large forces are needed to fracture it. Most pelvic fractures occur in high energy collisions; if the bony pelvis is disrupted, the soft organs and viscera are also threatened. Pelvic fractures often occur with substantial injuries to the trunk and limbs. The bony pelvis is effectively a ring, and disruption depends on there being at least two fractures or joint separations with consequent instability. The pelvis can be crushed in an antero-posterior, lateral or vertical direction or a combination of all three. Life-threatening internal bleeding from arterial or, most importantly, venous injury to the iliac vessels often accompanies pelvic fractures.

Clinical indications of likely pelvic fracture include:

• Haematuria or in males, signs of urethral injury, e.g. high-riding prostate on rectal examination, scrotal haematoma or blood at urethral meatus

• Rectal bleeding, or a large haematoma or palpable fracture line on rectal examination

• Haematomas of the proximal thigh, above the inguinal ligament, over the perineum or in the flank

A plain AP pelvic X-ray reveals 90% of injuries. If a fracture is present or suspected and the patient stable, a pelvic CT scan is the best imaging for pelvic anatomy (including hip dislocation and acetabular fracture) and shows the extent of pelvic, retroperitoneal and intraperitoneal bleeding. Rapid assessment, then temporary stabilisation with a fabric pelvic-binder applied in the accident department may help arrest the bleeding, but transfusion and angiographic embolisation may be needed.

Spinal fractures (Fig. 15.10): These may be pathological or not. The most common pathological fracture is a fragility (crush) fracture in osteoporotic bone, typically in lumbar spine bodies in older patients. Up to 90% of patients in their 80s are believed to have sustained a vertebral fragility crush fracture. These cause pain and disability but do not benefit from surgical treatment and take time to settle. Pathological fractures through metastatic deposits are a common new presentation of a known neoplasm or of an undiagnosed primary.

• Patient alert and orientated

• No abnormal neurological signs

• No significant other injury that may distract the patient from complaining about the spine

• On examination: no bruising or deformity around the neck, no tenderness and a normal pain-free range of active movement

A cervical spine CT scan should be performed (usually with a CT head) if the criteria are not met. Thoracolumbar spine imaging is indicated if there is pain, bruising, swelling, deformity or abnormal neurological signs attributable to the region. A fracture anywhere in the spine is an indication for full spinal imaging. Unconscious patients cannot be assessed clinically and require radiological clearance of the whole spine (i.e. exclusion of injuries). If in doubt, spinal immobilisation devices are left in place, logrolling for movement and high frequency nursing care is continued while seeking detail about the fracture.

Common ligamentous injuries

Dislocations: Certain joints can sublux or dislocate after a ligament sprain or rupture. Subluxation is when there is partial loss of congruity between articular surfaces and dislocation is when there is total loss of congruity. Some joints are predisposed to this by their shape and inherent mobility. Sometimes a systemic disease such as the collagen disorder Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, or muscle weakness in muscular dystrophy contributes instability enough for joints to dislocate.