Chapter 298 Major Symptoms and Signs of Digestive Tract Disorders

Disorders of organs outside the gastrointestinal (GI) tract can produce symptoms and signs that mimic digestive tract disorders and should be considered in the differential diagnosis (Table 298-1). In children with normal growth and development, treatment may be initiated without a formal evaluation based on a presumptive diagnosis after taking a history and performing a physical examination. Poor weight gain or weight loss is often associated with a significant pathologic process and usually necessitates a more formal evaluation.

Table 298-1 SOME NONDIGESTIVE TRACT CAUSES OF GASTROINTESTINAL SYMPTOMS IN CHILDREN

ANOREXIA

Systemic disease: inflammatory, neoplastic

Cardiorespiratory compromise

Iatrogenic: drug therapy, unpalatable therapeutic diets

Depression

Anorexia nervosa

VOMITING

Inborn errors of metabolism

Medications: erythromycin, chemotherapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Increased intracranial pressure

Brain tumor

Infection of the urinary tract

Labyrinthitis

Adrenal insufficiency

Pregnancy

Psychogenic

Abdominal migraine

Toxins

Renal disease

DIARRHEA

Infection: otitis media, urinary

Uremia

Medications: antibiotics, cisapride

Tumors: neuroblastoma

Pericarditis

CONSTIPATION

Hypothyroidism

Spina bifida

Psychomotor retardation

Dehydration: diabetes insipidus, renal tubular lesions

Medications: narcotics

Lead poisoning

Infant botulism

ABDOMINAL PAIN

Pyelonephritis, hydronephrosis, renal colic

Pneumonia

Pelvic inflammatory disease

Porphyria

Angioedema

Endocarditis

Abdominal migraine

Familial Mediterranean fever

Sexual or physical abuse

Systemic lupus erythematosus

School phobia

Sickle cell crisis

Vertebral disk inflammation

Psoas abscess

Pelvic osteomyelitis

Medications

ABDOMINAL DISTENTION OR MASS

Ascites: nephrotic syndrome, neoplasm, heart failure

Discrete mass: Wilms tumor, hydronephrosis, neuroblastoma, mesenteric cyst, hepatoblastoma, lymphoma

Pregnancy

JAUNDICE

Hemolytic disease

Urinary tract infection

Sepsis

Hypothyroidism

Panhypopituitarism

Dysphagia

Difficulty in swallowing is termed dysphagia. Painful swallowing is termed odynophagia. Globus is the sensation of something stuck in the throat without a clear etiology. Swallowing is a complex process that starts in the mouth with mastication and lubrication of food that is formed into a bolus. The bolus is pushed to the pharynx by the tongue. The pharyngeal phase of swallowing is rapid and involves protective mechanisms to prevent food from entering the airway. The epiglottis is lowered over the larynx while the soft palate is elevated against the nasopharyngeal wall; respiration is temporarily arrested while the upper esophageal sphincter opens to allow the bolus to enter the esophagus. In the esophagus, peristaltic coordinated muscular contractions push the food bolus toward the stomach. The lower esophageal sphincter relaxes shortly after the upper esophageal sphincter, so liquids that rapidly clear the esophagus enter the stomach without resistance.

Dysphagia is classified as oropharyngeal dysphagia and esophageal dysphagia. Oropharyngeal dysphagia occurs when the transfer of the food bolus from the mouth to the esophagus is impaired (also termed transfer dysphagia). The striated muscles of the mouth, pharynx, and upper esophageal sphincter are affected in oropharyngeal dysphagia. Neurologic and muscular disorders can give rise to oropharyngeal dysphagia (Table 298-2). The most serious complication of oropharyngeal dysphagia is life-threatening aspiration.

Table 298-2 CAUSES OF OROPHARYNGEAL DYSPHAGIA

NEUROMUSCULAR DISORDERS

Cerebral palsy

Brain tumors

Cerebrovascular accidents

Polio and postpolio syndromes

Multiple sclerosis

Myositis

Dermatomyositis

Myasthenia gravis

Muscular dystrophies

METABOLIC AND AUTOIMMUNE DISORDERS

Hyperthyroidism

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Sarcoidosis

Amyloidosis

INFECTIOUS DISEASE

Meningitis

Botulism

Diphtheria

Lyme disease

Neurosyphilis

Viral infection: polio, Coxsackievirus, herpes, cytomegalovirus

STRUCTURAL LESIONS

Inflammatory: abscess, pharyngitis

Congenital web

Cricopharyngeal bar

Dental problems

Bullous skin lesions

Plummer- Vinson syndrome

Zenker diverticulum

Extrinsic compression: osteophytes, lymph nodes, thyroid swelling

OTHER

Corrosive injury

Side effects of medications

After surgery

After radiation therapy

Adapted from Gasiorowska A, Faas R: Current approach to dysphagia, Gastroenterol Hepatol 5(4):269–279, 2009.

A complex sequence of neuromuscular events is involved in the transfer of foods to the upper esophagus. Abnormalities of the muscles involved in the ingestion process and their innervation, strength, or coordination are associated with transfer dysphagia in infants and children. In such cases, an oropharyngeal problem is usually part of a more generalized neurologic or muscular problem (botulism, diphtheria, neuromuscular disease). Painful oral lesions, such as acute viral stomatitis or trauma, occasionally interfere with ingestion. If the nasal air passage is seriously obstructed, the need for respiration causes severe distress when suckling. Although severe structural, dental, and salivary abnormalities would be expected to create difficulties, ingestion proceeds relatively well in most affected children if they are hungry.

Esophageal dysphagia occurs when there is difficulty in transporting the food bolus down the esophagus. Esophageal dysphagia can result from neuromuscular disorders or mechanical obstruction (Table 298-3). Primary motility disorders causing impaired peristaltic function and dysphagia are rare in children. Achalasia is an esophageal motility disorder with associated inability of relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter, and it rarely occurs in children. Motility of the distal esophagus is disordered after surgical repair of tracheoesophageal fistula or achalasia. Abnormal motility can accompany collagen vascular disorders. Mechanical obstruction can be intrinsic or extrinsic. Intrinsic structural defects cause a fixed impediment to the passage of food bolus due to a narrowing within the esophagus, as in a stricture, web, or tumor. Extrinsic obstruction is due to compression from vascular rings, mediastinal lesions, or vertebral abnormalities. Structural defects typically cause more problems in swallowing solids than liquids. In infants, esophageal web, tracheobronchial remnant, or vascular ring can cause dysphagia. An esophageal stricture secondary to esophagitis (chronic gastroesophageal reflux, eosinophilic esophagitis, chronic infections) occasionally has dysphagia as the first manifestation. An esophageal foreign body or a stricture secondary to a caustic ingestion also causes dysphagia. A Schatzki ring, a thin ring of mucosal tissue near the lower esophageal sphincter, is another mechanical cause of recurrent dysphagia, and again is rare in children.

Table 298-3 CAUSES OF ESOPHAGEAL DYSPHAGIA

NEUROMUSCULAR DISORDERS

GERD

Achalasia cardia

Diffuse esophageal spasm

Scleroderma

MECHANICAL

Intrinsic Lesions

Foreign bodies

Esophagitis: GERD, eosinophilic esophagitis

Stricture: corrosive injury, pill induced, peptic

Esophageal webs

Esophageal rings

Esophageal diverticula

Neoplasm

Extrinsic Lesions

Vascular compression

Mediastinal lesion

Cervical osteochondritis

Vertebral abnormalities

GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Adapted from Gasiorowska A, Faas R: Current approach to dysphagia, Gastroenterol Hepatol 5(4):269–279, 2009.

When dysphagia is associated with a delay in passage through the esophagus, the patient may be able to point to the level of the chest where the delay occurs, but esophageal symptoms are usually referred to the suprasternal notch. When a patient points to the suprasternal notch, the impaction can be found anywhere in the esophagus.

Regurgitation

Regurgitation is the effortless movement of stomach contents into the esophagus and mouth. It is not associated with distress, and infants with regurgitation are often hungry immediately after an episode. The lower esophageal sphincter prevents reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus. Regurgitation is a result of gastroesophageal reflux through an incompetent or, in infants, immature lower esophageal sphincter. This is often a developmental process, and regurgitation or “spitting” resolves with maturity. Regurgitation should be differentiated from vomiting, which denotes an active reflex process with an extensive differential diagnosis (Table 298-4).

Table 298-4 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF EMESIS DURING CHILDHOOD

| INFANT | CHILD | ADOLESCENT |

|---|---|---|

| COMMON | ||

| Gastroenteritis Gastroesophageal reflux Overfeeding Anatomic obstruction* Systemic infection Pertussis syndrome Otitis media |

Gastroenteritis Systemic infection Gastritis Toxic ingestion Pertussis syndrome Medication Reflux (GERD) Sinusitis Otitis media Anatomic obstruction* |

Gastroenteritis GERD Systemic infection Toxic ingestion Gastritis Sinusitis Inflammatory bowel disease Appendicitis Migraine Pregnancy Medication Ipecac abuse, bulimia Concussion |

| RARE | ||

| Adrenogenital syndrome Inborn error of metabolism Brain tumor (increased intracranial pressure) Subdural hemorrhage Food poisoning Rumination Renal tubular acidosis Ureteropelvic junction obstruction |

Reye syndrome Hepatitis Peptic ulcer Pancreatitis Brain tumor Increased intracranial pressure Middle ear disease Chemotherapy Achalasia Cyclic vomiting (migraine) Esophageal stricture Duodenal hematoma Inborn error of metabolism |

Reye syndrome Hepatitis Peptic ulcer Pancreatitis Brain tumor Increased intracranial pressure Middle ear disease Chemotherapy Cyclic vomiting (migraine) Biliary colic Renal colic Diabetic ketoacidosis |

GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease.

* Includes malrotation, pyloric stenosis, intussusception.

Anorexia

Anorexia means prolonged lack of appetite. Hunger and satiety centers are located in the hypothalamus; it seems likely that afferent nerves from the GI tract to these brain centers are important determinants of the anorexia that characterizes many diseases of the stomach and intestine. Satiety is stimulated by distention of the stomach or upper small bowel, the signal being transmitted by sensory afferents, which are especially dense in the upper gut. Chemoreceptors in the intestine, influenced by the assimilation of nutrients, also affect afferent flow to the appetite centers. Impulses reach the hypothalamus from higher centers, possibly influenced by pain or the emotional disturbance of an intestinal disease. Other regulatory factors include hormones, ghrelin, leptin, and plasma glucose, which, in turn, reflect intestinal function (Chapter 44).

Vomiting

Vomiting is a highly coordinated reflex process that may be preceded by increased salivation and begins with involuntary retching. Violent descent of the diaphragm and constriction of the abdominal muscles with relaxation of the gastric cardia actively force gastric contents back up the esophagus. This process is coordinated in the medullary vomiting center, which is influenced directly by afferent innervation and indirectly by the chemoreceptor trigger zone and higher central nervous system (CNS) centers. Many acute or chronic processes can cause vomiting (see Tables 298-1 and 298-4).

Vomiting caused by obstruction of the GI tract is probably mediated by intestinal visceral afferent nerves stimulating the vomiting center (Table 298-5). If obstruction occurs below the 2nd part of the duodenum, vomitus is usually bile stained. Emesis can also become bile stained with repeated vomiting in the absence of obstruction when duodenal contents are refluxed into the stomach. Nonobstructive lesions of the digestive tract can also cause vomiting; this includes diseases of the upper bowel, pancreas, liver, or biliary tree. CNS or metabolic derangements can lead to severe, persistent emesis.

Table 298-5 CAUSES OF GASTROINTESTINAL OBSTRUCTION

ESOPHAGUS

Congenital

Esophageal atresia

Vascular rings

Schatzki ring

Tracheobronchial remnant

Acquired

Esophageal stricture

Foreign body

Achalasia

Chagas disease

Collagen vascular disease

STOMACH

Congenital

Antral webs

Pyloric stenosis

Acquired

Bezoar, foreign body

Pyloric stricture (ulcer)

Chronic granulomatous disease of childhood

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis

Crohn disease

Epidermolysis bullosa

SMALL INTESTINE

Congenital

Duodenal atresia

Annular pancreas

Malrotation/volvulus

Malrotation/Ladd bands

Ileal atresia

Meconium ileus

Meckel diverticulum with volvulus or intussusception

Inguinal hernia

Intestinal duplication

Acquired

Postsurgical adhesions

Crohn disease

Intussusception

Distal ileal obstruction syndrome (cystic fibrosis)

Duodenal hematoma

Superior mesenteric artery syndrome

COLON

Congenital

Meconium plug

Hirschsprung disease

Colonic atresia, stenosis

Imperforate anus

Rectal stenosis

Pseudo-obstruction

Volvulus

Colonic duplication

Acquired

Ulcerative colitis (toxic megacolon)

Chagas disease

Crohn disease

Fibrosing colonopathy (cystic fibrosis)

Cyclic vomiting is a syndrome with numerous episodes of vomiting interspersed with well intervals. The North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of cyclic vomiting criteria are listed in Table 298-6. Rome III criteria for Functional GI disorders (FGIDs) have 2 criteria for cyclic vomiting in children, and both these criteria have to be present for a diagnosis of cyclic vomiting: 2 or more periods of intense nausea and unremitting vomiting or retching lasting hours to days and return to usual state of health lasting weeks to months.

Table 298-6 CRITERIA FOR CYCLICAL VOMITING SYNDROME

All of the criteria must be met for the consensus definition of cyclical vomiting syndrome:

Li, B UK, Lefevre F, Chelimsky GG, et al: North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition Consensus Statement on the Diagnosis and Management of Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome, J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 47:379–393, 2008.

The onset of cyclic vomiting is usually between 2 and 5 yr of age but has been observed in infants and adults. The frequency of vomiting episodes is variable (average of 12 episodes per yr) with each episode typically lasting 2-3 days and 4 or more emesis episodes per hour. The episodes usually occur in the early hours of the morning or upon wakening. Patients can have a prodrome of nausea, pallor, intolerance of noise or light, lethargy, and headache. Epigastric pain, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and fever are seen in many patients, making the diagnosis difficult. Precipitants include infection, physical stress, and psychologic stress.

Several theories have been proposed as causative factors including a migraine-related mechanism, mitochondrial disorders, and autonomic dysfunction. More than 80% of affected children have a first-degree relative with migraines; many patients develop migraines later in life. Many children show evidence for sympathetic autonomic dysfunction of sudomotor systems. The differential diagnosis includes GI anomalies (malrotation, duplication cysts, choledochal cysts, recurrent intussusceptions), CNS disorders (neoplasm, epilepsy, vestibular pathology), nephrolithiasis, cholelithiasis, hydronephrosis, metabolic-endocrine disorders (urea cycle, fatty acid metabolism, Addison disease, porphyria, hereditary angioedema, familial Mediterranean fever), chronic appendicitis, and inflammatory bowel disease. Laboratory evaluation is based on a careful history and physical examination and may include, if indicated, endoscopy, contrast GI radiography, brain MRI, and metabolic studies (lactate, organic acids, ammonia). Treatment includes hydration and antiemetics (e.g., ondansetron). Prevention may be possible with lifestyle changes and prophylactic medications (cyproheptadine, propranolol, amitriptyline, phenobarbital) based on the patient’s age.

Potential complications of emesis are noted in Table 298-7. Broad management strategies for vomiting in general and specific causes of emesis are noted in Tables 298-8 and 298-9.

Table 298-7 COMPLICATIONS OF VOMITING

| COMPLICATION | PATHOPHYSIOLOGY | HISTORY, PHYSICAL EXAMINATION, AND LABORATORY STUDIES |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic | Fluid loss in emesis | Dehydration |

| HCl loss in emesis | Alkalosis; hypochloremia | |

| Na, K loss in emesis | Hyponatremia; hypokalemia | |

| Alkalosis → | ||

| • Na into cells | ||

| • HCO3 loss in urine | Urine pH 7-8 | |

| • Na and K loss in urine | Urine Na ↑, K ↑ | |

| Hypochloremia → Cl conserved by kidneys | Urine Cl ↓ | |

| Nutritional | Emesis of calories and nutrients Anorexia for calories and nutrients |

Malnutrition; “failure to thrive” |

| Mallory-Weiss tear | Retching → tear at lesser curve of gastroesophageal junction | Forceful emesis → hematemesis |

| Esophagitis | Chronic vomiting → esophageal acid exposure | Heartburn; hemoccult + stool |

| Aspiration | Aspiration of vomitus, especially in context of obtundation | Pneumonia; neurologic dysfunction |

| Shock | Severe fluid loss in emesis or in accompanying diarrhea | Dehydration (accompanying diarrhea can explain acidosis?) |

| Severe blood loss in hematemesis | Blood volume depletion | |

| Pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax | Increased intrathoracic pressure | Chest x-ray |

| Petechiae, retinal hemorrhages | Increased intrathoracic pressure | Normal platelet count |

From Kliegman RM, Greenbaum LA, Lye PS, editors: Practical strategies in pediatric diagnosis and therapy, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2004, Elsevier, p 318.

Table 298-8 PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPIES FOR VOMITING EPISODES

| THERAPEUTIC DRUG CLASS | DRUG | DOSAGE |

|---|---|---|

| REFLUX | ||

| Dopamine antagonist | Metoclopramide (Reglan) | 0.1-0.2 mg/kg PO or IV qid |

| GASTROPARESIS | ||

| Dopamine antagonist | Metoclopramide (Reglan) | 0.1-0.2 mg/kg PO or IV qid |

| Motilin agonist | Erythromycin | 3-5 mg/kg PO or IV tid-qid |

| INTESTINAL PSEUDO-OBSTRUCTION | ||

| Stimulation of intestinal migratory myoelectric complexes | Octreotide (Sandostatin) | 1 µg/kg SC bid-tid |

| CHEMOTHERAPY | ||

| Dopamine antagonist | Metoclopramide | 0.5-1.0 mg/kg IV qid, with antihistamine prophylaxis of extrapyramidal side effects |

| Serotoninergic 5-HT3 antagonist | Ondansetron (Zofran) | 0.15-0.3 mg/kg IV or PO tid |

| Phenothiazines (extrapyramidal, hematologic side effects) | Prochlorperazine (Compazine) | ≈0.3 mg/kg PO bid-tid |

| Chlorpromazine (Thorazine) | >6 mo of age: 0.5 mg/kg PO or IV tid-qid | |

| Steroids | Dexamethasone (Decadron) | 0.1 mg/kg PO tid |

| Cannabinoids | Tetrahydrocannabinol (Nabilone) | 0.05-0.1 mg/kg PO bid-tid |

| POSTOPERATIVE | ||

| Ondansetron, phenothiazines | See under chemotherapy | |

| MOTION SICKNESS, VESTIBULAR DISORDERS | ||

| Antihistamine | Dimenhydrinate (Dramamine) | 1 mg/kg PO tid-qid |

| Anticholinergic | Scopolamine (Transderm Scop) | Adults: 1 patch/3 days |

| ADRENAL CRISIS | ||

| Steroids | Cortisol | 2 mg/kg IV bolus followed by 0.2-0.4 mg/kg/hr IV (±1 mg/kg IM) |

| CYCLIC VOMITING SYNDROME | ||

| Supportive | ||

| Analgesic | Meperidine (Demerol) | 1-2 mg/kg IV or IM q4-6 hr |

| Anxiolytic, sedative | Lorazepam (Ativan) | 0.05-0.1 mg/kg IV q6hr |

| Antihistamine, sedative | Diphenhydramine (Benadryl) | 1.25 mg/kg IV q6hr |

| Abortive | ||

| Serotoninergic 5-HT3 antagonist: | Ondansetron | See above |

| Granisetron (Kytril) | 10 µg/kg IV q4-6 hr | |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent (GI ulceration side effect) | Ketorolac (Toradol) | 0.5-1.0 mg/kg IV q6-8 hr |

| Serotoninergic 5-HT1D agonist | Sumatriptan (Imitres) | >40 kg: 20 mg intranasally or 25 mg PO, one time only |

| PROPHYLACTIC* | ||

| Antimigraine, β-adrenergic blocker | Propranolol (Inderal) | 0.5-2.0 mg/kg PO bid |

| Antimigraine, antihistamine | Cyproheptadine (Periactin) | 0.25-0.5 mg/kg/day PO ÷ bid-tid |

| Antimigraine, tricyclic antidepressant | amitriptyline (Elavil) | 0.33-0.5 mg/kg PO tid, and titrate to maximum of 3.0 mg/kg/day as needed Obtain baseline ECG at start of therapy, and consider monitoring drug levels |

| Antimigraine antiepileptic | Phenobarbital (Luminal) | 2-3 mg/kg qhs |

| Erythromycin (see above) | ||

| Low-estrogen oral contraceptives | Consider for catamenial CVS episodes | |

CVS, cyclic vomiting syndrome; ECG, electrocardiogram; GI, gastrointestinal.

* If >1 CVS bout/month or symptoms are extremely disabling; taken daily.

From Kliegman RM, Greenbaum LA, Lye PS, editors: Practical strategies in pediatric diagnosis and therapy, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2004, Elsevier, p 317.

Table 298-9 SUPPORTIVE AND NONPHARMACOLOGIC THERAPIES FOR VOMITING EPISODES

| DISEASE | THERAPY |

|---|---|

| All |

ComplicationsDehydrationIV fluids, electrolytesHematemesisTransfuse, correct coagulopathyEsophagitisH2RAs, PPIsMalnutritionNG or NJ drip feeding useful for many chronic conditionsMeconium ileusGastrografin enemaDIOSGastrografin enema; balanced colonic lavage solution (e.g., GoLytely)IntussusceptionBarium enema; air reduction enemaHematemesisEndoscopic: injection sclerotherapy or banding of esophageal varices; injection therapy, fibrin sealant application, or heater probe electrocautery for selected upper GI tract lesionsSigmoid volvulusColonoscopic decompressionRefluxPositioning; dietary measures (infants: rice cereal, 1 tbs/oz of formula)Psychogenic componentsPsychotherapy; tricyclic antidepressants; anxiolytics (e.g., diazepam: 0.1 mg/kg PO tid-qid)

DIOS, distal intestinal obstruction syndrome; GI, gastrointestinal; H2RA, H2-receptor antagonist; NG, nasogastric; NJ, nasojejunal; PPIs, proton pump inhibitors; tbs, tablespoon.

From Kliegman RM, Greenbaum LA, Lye PS, editors: Practical strategies in pediatric diagnosis and therapy, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2004, Elsevier, p 319.

Diarrhea

Diarrhea is best defined as excessive loss of fluid and electrolyte in the stool. Acute diarrhea is defined as sudden onset of excessively loose stools of >10 mL/kg/day in infants and >200 g/24 hr in older children, which lasts <14 days. When the episode lasts >14 days, it is called chronic or persistent diarrhea.

Normally, a young infant has approximately 5 mL/kg/day of stool output; the volume increases to 200 g/24 hr in an adult. The greatest volume of intestinal water is absorbed in the small bowel; the colon concentrates intestinal contents against a high osmotic gradient. The small intestine of an adult can absorb 10-11 L/day of a combination of ingested and secreted fluid, whereas the colon absorbs approximately 0.5 L. Disorders that interfere with absorption in the small bowel tend to produce voluminous diarrhea, whereas disorders compromising colonic absorption produce lower-volume diarrhea. Dysentery (small-volume, frequent bloody stools with mucus, tenesmus, and urgency) is the predominant symptom of colitis.

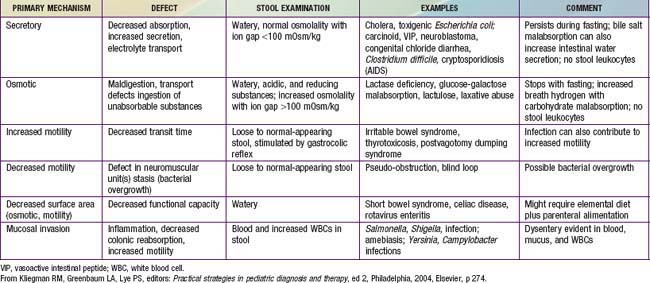

The basis of all diarrheas is disturbed intestinal solute transport and water absorption. Water movement across intestinal membranes is passive and is determined by both active and passive fluxes of solutes, particularly sodium, chloride, and glucose. The pathogenesis of most episodes of diarrhea can be explained by secretory, osmotic, or motility abnormalities or a combination of these (Table 298-10).

Secretory diarrhea occurs when the intestinal epithelial cell solute transport system is in an active state of secretion. It is often caused by a secretagogue, such as cholera toxin, binding to a receptor on the surface epithelium of the bowel and thereby stimulating intracellular accumulation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) or cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). Some intraluminal fatty acids and bile salts cause the colonic mucosa to secrete through this mechanism. Diarrhea not associated with an exogenous secretagogue can also have a secretory component (congenital microvillus inclusion disease). Secretory diarrhea is usually of large volume and persists even with fasting. The stool osmolality is indicated by the electrolytes and the ion gap is 100 mOsm/kg or less. The ion gap is calculated by subtracting the concentration of electrolytes from total osmolality:

Osmotic diarrhea occurs after ingestion of a poorly absorbed solute. The solute may be one that is normally not well absorbed (magnesium, phosphate, lactulose, or sorbitol) or one that is not well absorbed because of a disorder of the small bowel (lactose with lactase deficiency or glucose with rotavirus diarrhea). Malabsorbed carbohydrate is fermented in the colon, and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are produced. Although SCFAs can be absorbed in the colon and used as an energy source, the net effect is increase in the osmotic solute load. This form of diarrhea is usually of lesser volume than a secretory diarrhea and stops with fasting. The osmolality of the stool will not be explained by the electrolyte content, because another osmotic component is present and the anion gap is >100 mOsm.

Motility disorders can be associated with rapid or delayed transit and are not generally associated with large-volume diarrhea. Slow motility can be associated with bacterial overgrowth leading to diarrhea. The differential diagnosis of common causes of acute and chronic diarrhea is noted in Table 298-11.

Table 298-11 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF DIARRHEA

| INFANT | CHILD | ADOLESCENT |

|---|---|---|

| ACUTE | ||

| Common | ||

| Gastroenteritis (viral > bacterial) Systemic infection Antibiotic associated Overfeeding |

Gastroenteritis (viral > bacterial) Food poisoning Systemic infection Antibiotic associated |

Gastroenteritis (viral > bacterial) Food poisoning Antibiotic associated |

| Rare | ||

| Primary disaccharidase deficiency Hirschsprung toxic colitis Adrenogenital syndrome Neonatal opiate withdrawal |

Toxic ingestion Hemolytic uremic syndrome Intussusception |

Hyperthyroidism Appendicitis |

| CHRONIC | ||

| Common | ||

| Postinfectious secondary lactase deficiency Cow’s milk or soy protein intolerance Chronic nonspecific diarrhea of infancy Excessive fruit juice (sorbitol) ingestion Celiac disease Cystic fibrosis AIDS enteropathy |

Postinfectious secondary lactase deficiency Irritable bowel syndrome Celiac disease Lactose intolerance Excessive fruit juice (sorbitol) ingestion Giardiasis Inflammatory bowel disease AIDS enteropathy |

Irritable bowel syndrome Inflammatory bowel disease Lactose intolerance Giardiasis Laxative abuse (anorexia nervosa) Constipation with encopresis |

| Rare | ||

| Primary immune defects Glucose-galactose malabsorption Microvillus inclusion disease (microvillus atrophy) Congenital transport defects (chloride, sodium) Primary bile acid malabsorption Factitious syndrome by proxy Hirschsprung disease Shwachman syndrome Secretory tumors Acrodermatitis enteropathica Lymphangiectasia Abetalipoproteinemia Eosinophilic gastroenteritis Short bowel syndrome Intractable diarrhea syndrome Autoimmune enteropathy |

Acquired immune defects Secretory tumors Pseudo-obstruction Sucrase-isomaltase deficiency Eosinophilic gastroenteritis |

Secretory tumor Primary bowel tumor Parasitic infections and venereal diseases Appendiceal abscess Addison disease |

From Kliegman RM, Greenbaum LA, Lye PS, editors: Practical strategies in pediatric diagnosis and therapy, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2004, Elsevier, p 272.

Constipation

Any definition of constipation is relative and depends on stool consistency, stool frequency, and difficulty in passing the stool. A normal child might have a soft stool only every 2nd or 3rd day without difficulty; this is not constipation. A hard stool passed with difficulty every 3rd day should be treated as constipation. Constipation can arise from defects either in filling or emptying the rectum (Table 298-12).

A nursing infant might have very infrequent stools of normal consistency; this is usually a normal pattern. True constipation in the neonatal period is most likely secondary to Hirschsprung disease, intestinal pseudo-obstruction, or hypothyroidism.

Defective rectal filling occurs when colonic peristalsis is ineffective (in cases of hypothyroidism or opiate use and when bowel obstruction is caused either by a structural anomaly or by Hirschsprung disease). The resultant colonic stasis leads to excessive drying of stool and a failure to initiate reflexes from the rectum that normally trigger evacuation. Emptying the rectum by spontaneous evacuation depends on a defecation reflex initiated by pressure receptors in the rectal muscle. Stool retention, therefore, can also result from lesions involving these rectal muscles, the sacral spinal cord afferent and efferent fibers, or the muscles of the abdomen and pelvic floor. Disorders of anal sphincter relaxation can also contribute to fecal retention.

Constipation tends to be self-perpetuating, whatever its cause. Hard, large stools in the rectum become difficult and even painful to evacuate; thus, more retention occurs and a vicious circle ensues. Distention of the rectum and colon lessens the sensitivity of the defecation reflex and the effectiveness of peristalsis. Eventually, watery content from the proximal colon might percolate around hard retained stool and pass per rectum unperceived by the child. This involuntary encopresis may be mistaken for diarrhea. Constipation itself does not have deleterious systemic organic effects, but urinary tract stasis can accompany severe long-standing cases and constipation can generate anxiety, having a marked emotional impact on the patient and family.

Abdominal Pain

There is considerable variation among children in their perception and tolerance for abdominal pain. This is one reason the evaluation of chronic abdominal pain is difficult. A child with functional abdominal pain (no identifiable organic cause) may be as uncomfortable as one with an organic cause. It is very important to distinguish between organic and nonorganic (functional) abdominal pain because the approach for the management is based on this. Normal growth and physical examination (including a rectal examination) are reassuring in a child who is suspected of having functional pain.

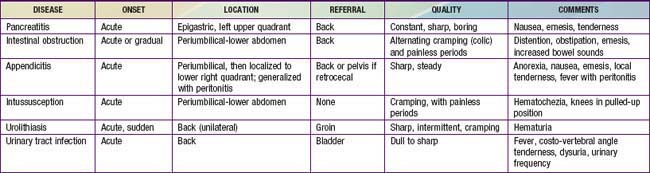

A specific cause may be difficult to find, but the nature and location of a pain-provoking lesion can usually be determined from the clinical description. Two types of nerve fibers transmit painful stimuli in the abdomen. In skin and muscle, A fibers mediate sharp localized pain; C fibers from viscera, peritoneum, and muscle transmit poorly localized, dull pain. These afferent fibers have cell bodies in the dorsal root ganglia, and some axons cross the midline and ascend to the medulla, midbrain, and thalamus. Pain is perceived in the cortex of the postcentral gyrus, which can receive impulses arising from both sides of the body. In the gut, the usual stimulus provoking pain is tension or stretching. Inflammatory lesions can lower the pain threshold, but the mechanisms producing pain of inflammation are not clear. Tissue metabolites released near nerve endings probably account for the pain caused by ischemia. Perception of these painful stimuli can be modulated by input from both cerebral and peripheral sources. Psychologic factors are particularly important. Features of abdominal pain are noted in Tables 298-13 and 298-14. Pain that suggests a potentially serious organic etiology is associated with age <5 yr; fever; weight loss; bile or blood-stained emesis; jaundice; hepatosplenomegaly; back or flank pain or pain in a location other than the umbilicus; awakening from sleep in pain; referred pain to shoulder, groin or back; elevated ESR, WBC, or CRP; anemia; edema; or a strong family history of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or celiac disease.

Table 298-13 CHRONIC ABDOMINAL PAIN IN CHILDREN

| DISORDER | CHARACTERISTICS | KEY EVALUATIONS |

|---|---|---|

| NONORGANIC | ||

| Functional abdominal pain | Nonspecific pain, often periumbilical | Hx and PE; tests as indicated |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | Intermittent cramps,diarrhea, and constipation | Hx and PE |

| Non-ulcer dyspepsia | Peptic ulcer–like symptoms without abnormalities on evaluation of the upper GI tract | Hx; esophagogastroduodenoscopy |

| GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT | ||

| Chronic constipation | Hx of stool retention, evidence of constipation on examination | Hx and PE; plain x-ray of abdomen |

| Lactose intolerance | Symptoms may be associated with lactose ingestion; bloating, gas, cramps, and diarrhea | Trial of lactose-free diet; lactose breath hydrogen test |

| Parasite infection (especially Giardia) | Bloating, gas, cramps, and diarrhea | Stool evaluation for O&P; specific immunoassays for Giardia |

| Excess fructose or sorbitol ingestion | Nonspecific abdominal pain, bloating, gas, and diarrhea | Large intake of apples, fruit juice, or candy or chewing gum sweetened with sorbitol |

| Crohn disease | See Chapter 328 | |

| Peptic ulcer | Burning or gnawing epigastric pain; worse on awakening or before meals; relieved with antacids | Esophagogastroduodenoscopy or upper GI contrast x-rays |

| Esophagitis | Epigastric pain with substernal burning | Esophagogastroduodenoscopy |

| Meckel’s diverticulum | Periumbilical or lower abdominal pain; may have blood in stool | Meckel scan or enteroclysis |

| Recurrent intussusception | Paroxysmal severe cramping abdominal pain; blood may be present in stool with episode | Identify intussusception during episode or lead point in intestine between episodes with contrast studies of GI tract |

| Internal, inguinal, or abdominal wall hernia | Dull abdomen or abdominal wall pain | PE, CT of abdominal wall |

| Chronic appendicitis or appendiceal mucocele | Recurrent RLQ pain; often incorrectly diagnosed, may be rare cause of abdominal pain | Barium enema, CT |

| GALLBLADDER AND PANCREAS | ||

| Cholelithiasis | RUQ pain, might worsen with meals | Ultrasound of gallbladder |

| Choledochal cyst | RUQ pain, mass ± elevated bilirubin | Ultrasound or CT of RUQ |

| Recurrent pancreatitis | Persistent boring pain, might radiate to back, vomiting | Serum amylase and lipase ± serum trypsinogen; ultrasound or CT of pancreas |

| GENITOURINARY TRACT | ||

| Urinary tract infection | Dull suprapubic pain, flank pain | Urinalysis and urine culture; renal scan |

| Hydronephrosis | Unilateral abdominal or flank pain | Ultrasound of kidneys |

| Urolithiasis | Progressive, severe pain; flank to inguinal region to testicle | Urinalysis, ultrasound, IVP, CT |

| Other genitourinary disorders | Suprapubic or lower abdominal pain; genitourinary symptoms | Ultrasound of kidneys and pelvis; gynecologic evaluation |

| MISCELLANEOUS CAUSES | ||

| Abdominal migraine | See text; nausea, family Hx migraine | Hx |

| Abdominal epilepsy | Might have seizure prodrome | EEG (can require >1 study, including sleep-deprived EEG) |

| Gilbert syndrome | Mild abdominal pain (causal or coincidental?); slightly elevated unconjugated bilirubin | Serum bilirubin |

| Familial Mediterranean fever | Paroxysmal episodes of fever, severe abdominal pain, and tenderness with other evidence of polyserositis | Hx and PE during an episode, DNA diagnosis |

| Sickle cell crisis | Anemia | Hematologic evaluation |

| Lead poisoning | Vague abdominal pain ± constipation | Serum lead level |

| Henoch-Schönlein purpura | Recurrent, severe crampy abdominal pain, occult blood in stool, characteristic rash, arthritis | Hx, PE, urinalysis |

| Angioneurotic edema | Swelling of face or airway, crampy pain | Hx, PE, upper GI contrast x-rays, serum C1 esterase inhibitor |

| Acute intermittent porphyria | Severe pain precipitated by drugs, fasting, or infections | Spot urine for porphyrins |

abd, abdominal; EEG, electroencephalogram; GI, gastrointestinal; Hx, history; IVP, intravenous pyelogrophy; O&P, ova and parasites; PE, physical exam; RLQ, right lower quadrant; RUQ, right upper quadrant.

Visceral pain tends to be dull and aching and is experienced in the dermatome from which the affected organ receives innervations. So, most often, the pain and tenderness is not felt over the site of the disease process. Painful stimuli originating in the liver, pancreas, biliary tree, stomach, or upper bowel are felt in the epigastrium; pain from the distal small bowel, cecum, appendix, or proximal colon is felt at the umbilicus; and pain from the distal large bowel, urinary tract, or pelvic organs is usually suprapubic. The pain from the cecum, ascending colon, and descending colon sometimes is felt at the site of the lesion due to the short mesocecum and corresponding mesocolon. The pain due to appendicitis is initially felt in the periumbilical region, and pain from the transverse colon is usually felt in the supra pubic region. The shifting (localization) of pain is a pointer toward diagnosis; for example, periumbilical pain of a few hours localizing to the right lower quadrant suggests appendicitis. Radiation of pain can be helpful in diagnosis; for example, in biliary colic the radiation of pain is toward the inferior angle of the right scapula, pancreatic pain radiated to the back, and the renal colic pain is radiated to the inguinal region on the same side.

Somatic pain is intense and is usually well localized. When the inflamed viscus comes in contact with the somatic organ like the parietal peritoneum or the abdominal wall, pain is localized to that site. Peritonitis gives rise to generalized abdominal pain with rigidity, involuntary guarding, rebound tenderness, and cutaneous hyperesthesia on physical examination.

Referred pain from extraintestinal locations, due to shared central projections with the sensory pathway from the abdominal wall, can give rise to abdominal pain, as in pneumonia when the parietal pleural pain is referred to the abdomen.

Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage

Bleeding can occur anywhere along the GI tract, and identification of the site may be challenging (Table 298-15). Bleeding that originates in the esophagus, stomach, or duodenum can cause hematemesis. When exposed to gastric or intestinal juices, blood quickly darkens to resemble coffee grounds; massive bleeding is likely to be red. Red or maroon blood in stools, hematochezia, signifies either a distal bleeding site or massive hemorrhage above the distal ileum. Moderate to mild bleeding from sites above the distal ileum tends to cause blackened stools of tarry consistency (melena); major hemorrhages in the duodenum or above can also cause melena.

Table 298-15 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING IN CHILDHOOD

| INFANT | CHILD | ADOLESCENT |

|---|---|---|

| COMMON | ||

| Bacterial enteritis Milk protein allergy Intussusception Swallowed maternal blood Anal fissure Lymphonodular hyperplasia |

Bacterial enteritis Anal fissure Colonic polyps Intussusception Peptic ulcer/gastritis Swallowed epistaxis Prolapse (traumatic) gastropathy secondary to emesis Mallory-Weiss syndrome |

Bacterial enteritis Inflammatory bowel disease Peptic ulcer/gastritis Prolapse (traumatic) gastropathy secondary to emesis Mallory-Weiss syndrome Colonic polyps Anal fissure |

| RARE | ||

| Volvulus Necrotizing enterocolitis Meckel diverticulum Stress ulcer, gastritis Coagulation disorder (hemorrhagic disease of newborn) Esophagitis |

Esophageal varices Esophagitis Meckel diverticulum Lymphonodular hyperplasia Henoch-Schönlein purpura Foreign body Hemangioma, arteriovenous malformation Sexual abuse Hemolytic-uremic syndrome Inflammatory bowel disease Coagulopathy Duplication cyst |

Hemorrhoids Esophageal varices Esophagitis Pill ulcer Telangiectasia-angiodysplasia Graft versus host disease Duplication cyst |

Erosive damage to the mucosa of the GI tract is the most common cause of bleeding, although variceal bleeding secondary to portal hypertension occurs often enough to require consideration. Prolapse gastropathy producing subepithelial hemorrhage and Mallory-Weiss lesions secondary to mucosal tears associated with emesis are causes of upper intestinal bleeds. Vascular malformations are a rare cause in children; they are difficult to identify. Upper intestinal bleeding is evaluated with an EGD (esophagogastroduodenoscopy). Evaluation of the small intestine is facilitated by capsule endoscopy. The capsule-sized imaging device is swallowed in older children or placed endoscopically in younger children. Lower GI bleeding is investigated with a colonoscopy. In brisk intestinal bleeding of unknown location, a tagged red blood cell (RBC) scan is helpful in locating the site of the bleeding. Occult blood in stool is usually detected by using commercially available fecal occult blood testing cards, which are based on a chemical reaction between the chemical guaiac and oxidizing action of a substrate (hemoglobin), giving a blue color. The guaiac test is very sensitive, but random testing can miss chronic blood loss, which can lead to iron-deficiency anemia. GI hemorrhage can produce hypotension and tachycardia but rarely causes GI symptoms; brisk duodenal or gastric bleeding can lead to nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. The breakdown products of intraluminal blood might tip patients into hepatic coma if liver function is already compromised and can lead to elevation of serum bilirubin.

Abdominal Distention and Abdominal Masses

Enlargement of the abdomen can result from diminished tone of the wall musculature or from increased content: fluid, gas, or solid. Ascites, the accumulation of fluid in the peritoneal cavity, distends the abdomen both in the flanks and anteriorly when it is large in volume. This fluid shifts with movement of the patient and conducts a percussion wave. Ascitic fluid is usually a transudate with a low protein concentration resulting from reduced plasma colloid osmotic pressure of hypoalbuminemia and/or from raised portal venous pressure. In cases of portal hypertension, the fluid leak probably occurs from lymphatics on the liver surface and from visceral peritoneal capillaries, but ascites does not usually develop until the serum albumin level falls. Sodium excretion in the urine decreases greatly as the ascitic fluid accumulates and, thus, additional dietary sodium goes directly to the peritoneal space, taking with it more water. When ascitic fluid contains a high protein concentration, it is usually an exudate caused by an inflammatory or neoplastic lesion.

When fluid distends the gut, either obstruction or imbalance between absorption and secretion should be suspected. The factors causing fluid accumulation in the bowel lumen often cause gas to accumulate, too. The result may be audible gurgling noises. The source of gas is usually swallowed air, but endogenous flora can increase considerably in malabsorptive states and produce excessive gas when substrate reaches the lower intestine. Gas in the peritoneal cavity (pneumoperitoneum) is usually due to perforated viscus and can cause abdominal distention depending on the amount of gas leak. A tympanitic percussion note, even over solid organs such as the liver, indicates a large collection of gas in the peritoneum.

An abdominal organ can enlarge diffusely or be affected by a discrete mass. In the digestive tract, such discrete masses can occur in the lumen, wall, omentum, or mesentery. In a constipated child, mobile, nontender fecal masses are often found. Congenital anomalies, cysts, or inflammatory processes can affect the wall of the gut. Gut wall neoplasms are extremely rare in children. The pathologic enlargement of liver, spleen, bladder, and kidneys can give rise to abdominal distention.

Jaundice

See Chapters 96.3 and 348.

American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Chronic Abdominal Pain. Chronic abdominal pain in children. Pediatrics. 2003;115:812-815.

American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee and NASPGHAN Committee on Chronic Abdominal Pain. Chronic abdominal pain in children: a technical report of the American Academy of Pediatrics and the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;40:249-261.

American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee and NASPGHAN Committee on Chronic Abdominal Pain. Chronic abdominal pain in children: a clinical report of the American Academy of Pediatrics and the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;40:245-248.

Boyle JT. Abdominal pain. In: Walker WA, Kleinman RE, Sherman PM, et al, editors. Pediatric gastrointestinal disease: pathophysiology, diagnosis, management. ed 4. Shelton, CT: PMPH-USA; 2004:225-243.

Carty HM. Paediatric emergencies: non-traumatic abdominal emergencies. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:2835-2848.

Carvalho RS, Michail SK, Ashai-Khan F, Mezoff AG. An update in pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition: a review of some recent advances. Curr Prob Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2008;38:197-234.

Chelimsky TC, Chelimsky GG. Autonomic abnormalities in cyclic vomiting. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44:326-330.

Fitzpatrick E, Bourke B, Drumm B, Rowland M. Outcome for children with cyclical vomiting syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92:1001-1004.

Gasiorowska A, R Faas R. Current approach to dysphagia. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;5:269-279.

Golden CB, Feusner JH. Malignant abdominal masses in children: quick guide to evaluation and diagnosis. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2002;49:1369-1392.

Guandalini S, Frye RE: Diarrhea. eMedicine Updated: Jan 5, 2009.

Li BU, Misiewicz L. Cylic vomiting syndrome: a brain-gut disorder. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2003;32:997-1019.

Mulvaney S, Lombert EW, Garber J, Walker LS. Trajectories of symptoms and impairment for pediatric patients with functional abdominal pain. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:737-744.

The North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. Consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of cyclical vomiting. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47:379-393.

Rasquin A, Di Lorenzo C, Forbes D, et al. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: child/adolescent. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1527-1537.

Rome Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Home page. (website) http://www.romecriteria.org, 2010. Accessed April 28

Rubin G. Constipation in children. Clin Evid. 2003;10:369-374.

Venkatesan T, Li BUK, Marcus S, et al. Cyclic vomiting syndrome. (website) http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/933135-overview, 2010. Accessed April 28