Major incidents

Introduction

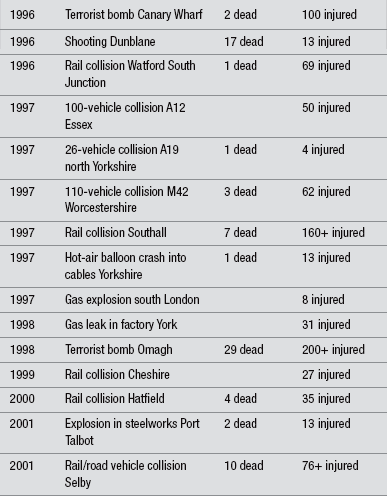

Incidents involving large numbers of injured individuals are not as uncommon as people may like to believe, although over the years the profiles of these incidents have changed. Incidents are often associated with industry, transportation, mass gatherings, and terrorism. Carley & Mackway-Jones (2005) found on average, 3–4 major incidents occurred in the UK every year from 1966 to 1996 (range 0–11). Table 3.1 lists a few examples of incidents occurring over the last 20 years in the UK.

This chapter discusses the role of the health services in contingency planning and service provision for major incidents. Consideration will be given to hospital-based activity, both in general terms and specifically in relation to in-hospital emergency services. The on-scene response to a major incident is considered in Chapter 1.

In England the primary source of guidance to assist the NHS in planning a response to a major incident is contained in the Department of Health Emergency Preparedness Division (2007) Mass Casualties Incidents: A Framework for Planning, which is influenced by the requirements of the Civil Contingencies Act 2004 (Home Office 2004). Guidance for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland is issued by the Health Departments of each of the Administrations.

Definition

Guidance from the Department of Health (HSE1996a,b) defines a major incident as: ‘any occurrence that presents serious threat to the health of the community, disruption to service, or causes (or is likely to cause) such numbers or types of casualties as to require special arrangements to be implemented by hospitals, ambulance trusts or primary care organizations’.

This definition reflects the departure from the view that major incidents only result from the ‘big bang’ scenario such as a rail collision or a building collapse. Guidance now recognizes that major incidents can also occur in a variety of different ways (NHS Management Executive 1998, National Audit Office 2002), such as

• rising tide – such as a developing infectious disease epidemic or an outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease (Smith et al. 2005)

• cloud on the horizon – a serious incident elsewhere that may develop and need preparatory action such as a cloud of toxic gas from a fire at an industrial plant

• headline news – public alarm about a personal threat

• internal incident – such as a fire in the hospital or power failure

• deliberate – such as the release of chemical, biological, radiation or nuclear material

• pre-planned major events – such as sporting or entertainment mass gatherings.

Planning

Each NHS organization must have a major incident plan based upon risk assessment, cooperation with partners, communicating with the public, and information sharing. It is the Chief Executive’s responsibility to ensure such a plan is in place and to keep the Trust Board up to date with the plan (Department of Health Emergency Preparedness Division 2005, 2011).

The plan should outline actions for the acute Trust to discharge its responsibilities, namely:

• provide a safe and secure environment for the assessment and treatment of patients

• provide a safe and secure environment for staff that will ensure the health, safety and welfare of staff, including appropriate arrangements for the professional and personal indemnification of staff

• provide a clinical response, including provision of general support and specific/specialist healthcare to all casualties, victims and responders

• liaise with the ambulance service, local Primary Care Organizations (PCOs) including GPs, out-of-hours services, Minor Injuries Units (MIUs) and other primary care providers, other hospitals, independent sector providers, and other agencies in order to manage the impact of the incident

• ensure there is an operational response to provide at-scene medical cover using, for example, BASICS and other immediate-care teams where they exist; members of these teams will be trained to an appropriate standard; the Medical Incident Commander should not routinely be taken from the receiving hospital so as not to deplete resources

• ensure that the hospital reviews all its essential functions throughout the incident

• provide appropriate support to any designated receiving hospital or other neighbouring service that is substantially affected

• provide limited decontamination facilities and personal protective equipment to manage contaminated self-presenting casualties

• acute Trusts will be expected to establish a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with their local Fire and Rescue Service on decontamination

• acute Trusts will need to make arrangements to reflect national guidance from the Home Office for dealing with the bodies of contaminated patients who die at the hospital

• liaise with activated health emergency control centres and/or on call PCO Officers as appropriate

• maintain communications with relatives and friends of existing patients and those from the incident, the Casualty Bureau, the local community, the media and VIPs.

Training

There is an expectation that staff understand the role they would adopt in a major incident, have the competencies to fulfil that role and have received training to fulfil those competencies. There is some evidence to suggest that staff are not entirely familiar with the action they should take in a major incident (Carr et al. 2006, Milkhu et al. 2008, Linney et al. 2011). It is suggested that acute Trusts should consider providing annual training and development for staff to enable them to meet these expectations. There is also a requirement for all NHS organizations to undertake a live exercise every three years, a table-top exercise each year and a test of communication cascades every six months (Department of Health Emergency Preparedness Division 2005). However, despite these exercises their must be a recognition for acute hospital trusts to coordinate their role with the surrounding primary healthcare organizations, as they may also lack in preparedness (Day et al. 2010).

Large-scale exercises serve a number of purposes:

• enabling major incident plans to be tested

• allowing the rehearsal of practical skills in realistic environments

• working alongside other services, establishing working relationships with individuals and organizations likely to be involved in a true response.

In addition to table-top exercises, using computer video serious gaming technology, can create a near reality likeness to an actual event. Knight et al. (2010) developed serious gaming technology to support the decision making involved in triaging patients. The benefit of this technology compared with large exercises is that it is cheaper in terms of resources, and the student can revisit the situation again.

While selection, training, and motivation can be expected to create greater resilience in staff involved in major incidents than among the rest of the population, there is also evidence that staff are not completely immune to adverse effects of trauma work (Alexander 2005). Staff may be exposed to:

• gruesome sights, sounds and smells and other materials

• on-site dangers and interpersonal violence

• distressing survivor stories

• powerlessness – being unable to help at the level they wish.

It is important, therefore, to ensure staff have sufficient rest, exercise and opportunity to talk, when they feel able to do so, to those whom they trust (Alexander & Klein 2011).

Major incident alerting procedures

In the event of a ‘big bang’ major incident it is likely the ambulance service will be the first to become aware of the incident. In this case they will be responsible, on confirmation of the incident, for alerting all appropriate partners within the health community. That noted, there are plenty of examples of major incidents, such as the Omagh bombing in Northern Ireland in 1998 (Lavery & Horan 2005) and the Canterbury earthquake in New Zealand in 2011 (Dolan2011a,b, Dolan et al 2011) where patients presented to the ED some minutes before the first ambulances.

The hospital’s response to a major incident alert

Receipt of casualties

In the ED, arrangements should be made to receive and treat casualties with appropriate priority. On arrival at the hospital all patients should be re-triaged, documented and directed to an appropriate treatment area. However, in a mass casualty situation, managing a large number of casualties means that the view of ‘doing the greatest good for the greatest number’ (Jenkins et al. 2008) should be applied; a philosophy which is different in normal everyday ED work.

Hospital response

Restriction of access

It is advisable that hospital staff do not leave their own departments or come to the hospital until they are requested to do so via the recognized communication channels. A decision will also have to be made whether or not to use non-requested, non-hospital medical, nursing and other volunteers who offer their services. The potential legal ramifications of using possibly unqualified impostors and/or the possibility of negligence claims resulting from their practices may well outweigh any useful function that they may be able to perform.

The media

The media, which will no doubt have gathered at the hospital, should be provided with regular and accurate press releases. The media are under pressure during a major incident to meet deadlines and if they do not receive adequate and appropriate information they may set about seeking it out for themselves. It is not uncommon for members of the media to attempt to gain access to patients/relatives in ED and other clinical settings such as ITU and wards by pretending to be members of staff. Walter (2011) notes, however, that news reporting, particularly live from the scene, may give vital information to the more remote commanders and to the wider health response before the normal communication channels can generate a properly informed report. The needs of the media should be addressed in ways that will not compromise the emergency response of the hospital and its staff or the confidentiality of casualties and relatives. Only designated members of staff, who preferably have been prepared for this role, should address the media and only statements prepared in consultation with the appropriate emergency services and approved by the hospital’s major incident coordination team should be released. Any access to casualties and staff should be very carefully controlled, with ground rules being agreed and consent obtained before any interviews take place.

Medico-legal issues

Although staff are working under considerable pressure at the time of an incident, all documentation should be adequate, clear and accurate (Carvalho et al. 2011). Nurses should consider that the pressures of a major incident do not remove their professional accountability for practice, and they may well be asked to justify the actions that they took, both inside and outside the ED, at a later date. Staff should also be aware that the plan, including any action cards, is a written document and, as such, essentially becomes an approved policy document of the organization and provides standards and descriptions of expected activities against which the actions of staff may be judged by any investigation, whether internal or external.

Aftermath

During and in the aftermath of a major incident, it is important to recognize that both casualties and staff may be psychologically and/or spiritually affected by events that are outside the normal range of experience. As a consequence they may be at risk of developing post-trauma stress reactions and doubting long-held beliefs (Firth-Cozens et al. 2000).

Conclusion

Major incidents are rare, but they do happen. It is essential that organizations’ plans are based on risk assessment and take into account other major incident plans within the health community and the work of Local Resilience Fora. For the plans to be successful individuals need to be familiar with their role within the plans and the actions they need to take and to be appropriately skilled, trained and rehearsed for that role.

References

Alexander, D. Early mental health intervention after disasters. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2005;11(1):12–18.

Alexander, D., Klein, S. Major incidents. In: Smith J., Greaves I., Porter K., eds. Oxford Desk Reference: Major Trauma. Oxford: Oxford Medical Publications, 2011.

Carley, S., Mackway-Jones. Major Incident Medical Management and Support: The Practical Approach in the Hospital. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, Advanced Life Support Group; 2005.

Carr, E.R.M., Chatrath, P., Palan, P. Audit of doctors’ knowledge of major incident policies. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2006;88(3):313–315.

Carvalho, S., Reeves, M., Orford, J. Fundamental Aspects of Legal, Ethical and Professional Issues in Nursing, second ed. London: Quay Books; 2011.

Day, T., Challen, K., Walter, D. Major incident planning in primary care trusts in north-west England. Health Services Management Research. 2010;23:25–29.

Department of Health Emergency Preparedness Division. The NHS Emergency Planning Guidance. London: Department of Health; 2005.

Department of Health Emergency Preparedness Division. The NHS Emergency Planning Guidance: Planning for the management of burn-injured patients in the event of a major incident: interim strategic national guidance. London: Department of Health; 2011.

Dolan, B. Rising from the ruins. Nursing Standard. 2011;25(28):22–23.

Dolan, B. Emergency nursing in an earthquake zone. Emergency Nurse. 2011;19(1):12–15.

Dolan, B., Esson, A., Grainger, P., et al. Earthquake disaster response in Christchurch, New Zealand. Journal of Emergency Nursing. 2011;37(5):506–509.

Firth-Cozens, J., Midgley, S.J., Burgess, C. Questionnaire survey of post-traumatic stress disorder in doctors involved in the Omagh bombing. British Medical Journal. 2000;319:1609.

Home Office. Civil Contingencies Act. London: Home Office; 2004.

HSE Emergency Planning in the NHS: Health Services Arrangements for Dealing with Major Incidents, London, Department of Health, 1996;vol. 1.

HSE Emergency Planning in the NHS: Health Services Arrangements for Dealing with Major Incidents, London, Department of Health, 1996;vol. 2.

Knight, J.F., Carley, S., Tregunna, B., et al. Serious gaming technology in major incident training: A pragmatic controlled trial. Resuscitation. 2010;81:1175–1179.

Lavery, G.G., Horan, E. Clinical review: Communication and logistics in the response to the 1998 terrorist bombing in Omagh, Northern Ireland, Critical Care, 2005. [9, 401–408].

Linney, A.C.S., Kernohan, W.G., Higgins, R. The identification of competencies for an NHS response to chemical, biological, nuclear and explosive (CBRNe) emergencies. International Emergency Nursing. 2011;19:96–105.

Milkhu, C.S., Howell, D.C.J., Glynne, P.A., et al. Mass casualty incidents: Are NHS staff prepared? An audit of one NHS foundation trust. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2008;25(10):562–564.

National Audit Office. Facing the Challenge: NHS Emergency Planning in England. London: National Audit Office; 2002.

Smith, A.F., Wild, C., Law, J. The Barrow-in-Furness legionnaires’ outbreak: qualitative study of the hospital response and the role of the major incident plan. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2005;22(4):251–255.

Walter, D. Communication. In: Smith J., Greaves I., Porter K., eds. Oxford Desk Reference: Major Trauma. Oxford: Oxford Medical Publications, 2011.