29 Major Depression

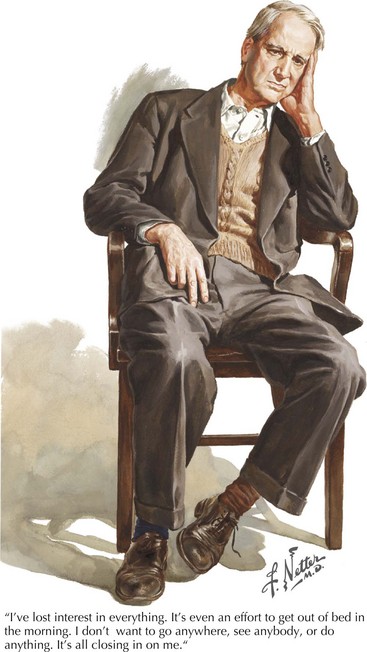

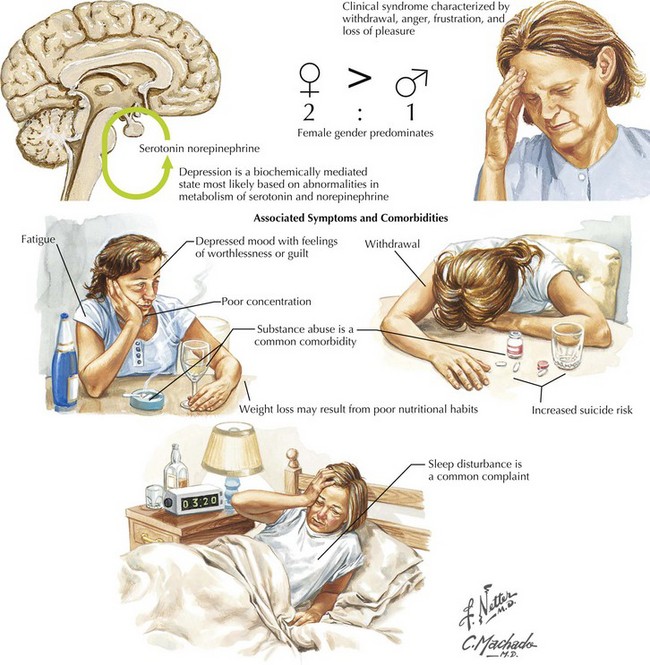

This vignette provides a classic picture of severe depression (Fig. 29-1). This is the most common serious psychiatric disorder; practicing physicians encounter it very frequently in many different guises. Depression is a very significant illness; it ranks second only to cardiovascular disease in overall morbidity and economic loss. Up to 20% of individuals within a general population will have at least one major depressive episode during their lifetime. Women have a higher incidence of depression between menarche and menopause, with an especially high risk postpartum. When depression affects men, the long-term risk of suicide is more common.

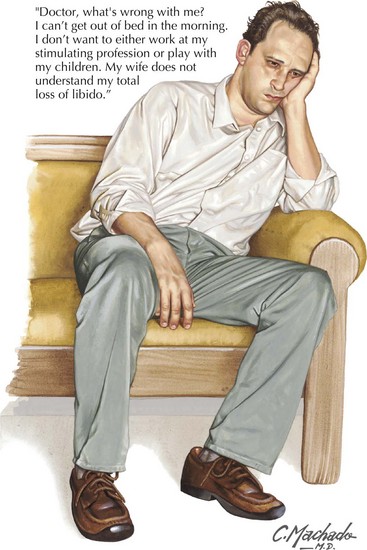

Depression usually begins in adolescence or early adulthood. It is a chronic illness with a propensity for recurrence. One common clinical pattern, called “double depression,” is characterized by repeated episodes of depression (Fig. 29-2) with eventual remission to a milder “dysthymic” state (Chapter 28). Familial clustering is apparent, although specific genes have not been identified. Depression beginning after age 60 years is probably a different disorder. It is less often associated with a significant family history but is associated with cerebrovascular disease and periventricular white matter abnormalities.

Clinical Presentation

One of the major medical concerns vis-à-vis any severely depressed patient is that suicide ideation and very definite attempts of the same are a common occurrence (Fig. 29-3). Although overt suicide attempts are notoriously difficult to predict, physicians must maintain a heightened sense of alertness to assessing suicide risk. One must always stand by to offer help and intervention per se when necessary, especially with the patient having significant suicidal risk factors. These include being a male, intense anxiety or agitation, social isolation, advanced age, history of previous suicide attempts, psychosis, and known alcohol abuse.

A primary bipolar disorder may underlie or be masked per se in at least 10% of individuals presenting with what appears on first pass to be unipolar depression. One single episode of mania will establish the bipolar diagnosis. A heightened level of suspicion for the presence of underlying bipolar disorder is necessary for anyone raised in a family with history of bipolar disorder, having experienced a childhood onset of depressive illness, or a poor therapeutic response. Similarly, if the patient experiences a sudden response to initiation of antidepressant medication, that is, “switching,” rather than following the usual delayed therapeutic response, a bipolar disorder requires further consideration. Efforts should be made to limit the exposure of patients with known or suspected bipolar disorder to the usual antidepressant medications (Chapter 30).

Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, et al. Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1987.

Blatt SJ. Experiences of Depression: Theoretical, Clinical and Research Perspectives. Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association; 2004.

Maeng S, Zarate CAJr. The role of glutamate in mood disorders: results from the ketamine in major depression study and the presumed cellular mechanism underlying its antidepressant effects. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007 Dec;9(6):467-474.

Mayberg HS. Defining the neural circuitry of depression: toward a new nosology with therapeutic implications. Biol. Psychiatry. 2007 Mar 15;61(6):729-730.

Mischoulon D. Update and critique of natural remedies as antidepressant treatments. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007 Mar;30(1):51-68.

Solomon, A. The Noonday Demon: an Atlas of Depression. Scribner: 2002.

Warden D, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, et al. The STAR*D Project results: a comprehensive review of findings. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007 Dec;9(6):449-459.