51 Lymphomas

Hodgkin’s lymphoma

Pathology

NLPHL accounts for 5% of HL cases and is more common in men.

Investigations and staging

Once the diagnosis has been made on biopsy, further investigations are needed to assess disease activity and the extent of its spread through the lymphoid system or other body sites. This is called staging and is essential for assessing prognosis, with cure rates for localised tumours (stage I or II) being much higher than those for widespread disease (stage IV). The staging of HL is assessed by the Cotswolds modification of the Ann Arbor classification system (Box 51.1). Information about prognostic factors such as mediastinal mass and bulky disease is included in the classification system. The tests required to establish the stage include a complete history, physical examination, FBC, urea and electrolytes (U and Es), chest X-ray and computed tomography (CT). Other useful tests include erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), serum LDH and liver function tests (LFTs). Positron emission tomography (PET) can be used to detect active residual disease.

Box 51.1 Cotswolds modification of the Ann Arbor classification system for Hodgkin’s lymphoma

| Clinical stage | Defining features |

|---|---|

| I | Involvement of a single lymph node region or lymphoid structure |

| II | Involvement of two or more lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm |

| III | Involvement of lymph node regions or structures on both sides of the diaphragm: |

B: fever, drenching sweats, weight loss

X: bulky disease

>one-third width of the mediastinum

>10 cm maximal dimension of nodal mass

E: involvement of a single extranodal site, contiguous or proximal to known nodal site

CS: clinical stage

PS: pathological stage

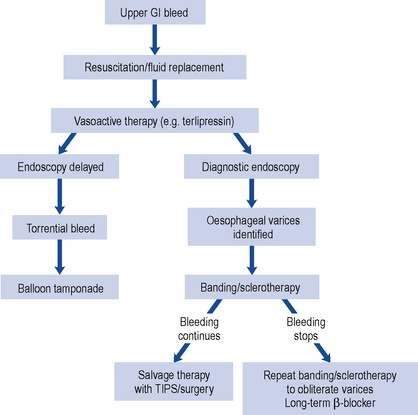

Management

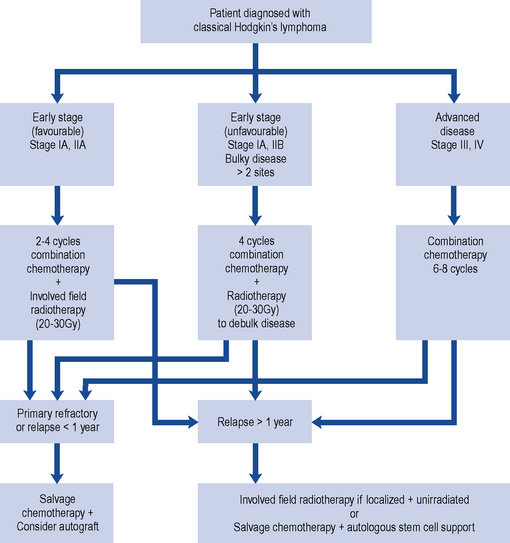

HL is potentially curable and, in general, sensitive to both chemotherapy and radiotherapy; therefore, the two main goals of treatment are to maximise the likelihood of cure whilst minimising the risk of late toxicity such as infertility. Stage of disease is the biggest factor in treatment choice and outcome. The management of classic HL is determined by the stage of the disease, and this is summarised in Fig. 51.1. Localised NLPHL frequently involves one isolated lymph node and tends to be indolent (slow growing). If there are no risk factors, it can be treated with IFRT alone (30 Gy); all other types are treated as advanced (stage III or IV) classic HL.

In Europe, the treatment of classic HL is determined by whether the disease is staged as early favourable disease, early unfavourable disease, advanced disease or relapsed (see Box 51.2).

Box 51.2 Disease staging for Hodgkin’s lymphoma (West of Scotland Blood Cancer Network, 2009)

Early stage

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) risk factors in localised disease

Early-stage (favourable) disease

The cure rate for patients with stages I and IIA disease is greater than 90%. Patients with stages I and IIA disease may be cured with radiotherapy alone (wide or extended field irradiation). However, due to radiation-related late effects, cardiac toxicity and secondary malignancy and the incidence of relapse (25–30%), most receive combined modality treatment (chemotherapy and radiotherapy). This usually consists of two to four cycles of ABVD (Adriamycin (doxorubicin), bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine) chemotherapy followed by IFRT of 20–30 Gy (Diehl et al., 2004). The aim of chemotherapy is to destroy subclinical disease outside the field of radiotherapy.

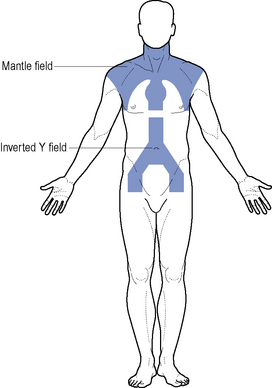

Where disease is confined to above the diaphragm, the mantle field is used (Fig. 51.2). The inverted Y is employed when the disease is confined below the diaphragm. This group of patients have a relapse-free survival rate of 80% at 5–10 years. Patients should be considered for entry into the National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) 18–30 study or NCRI Lymphoma Groups PET in Hodgkin’s Disease Study.

Advanced disease

Despite advances in HL, 30–40% of patients progress or relapse and respond poorly to salvage chemotherapy. A number of regimens have been investigated to both increase dose intensity and density of treatment, for example, BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, Adriamycin (doxorubicin), cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisolone) and escalated BEACOPP (Table 51.1). In a trial comparing escalated BEACOPP, standard BEACOPP and COPP-ABVD, escalated BEACOPP demonstrated increased overall survival compared with the other two treatment arms but at the cost of significant toxicity (Engert et al., 2009). First-line escalated BEACOPP can only be recommended currently as part of a clinical trial. A study to investigate the role of BEACOPP and PET imaging in patients with advanced HL is under way and will close in 2012 (UK Clinical Research Network Study Portfolio, 2010).

Table 51.1 Combination chemotherapy regimens effective in the treatment of Hodgkin’s lymphoma

| Regimen | Dose and route | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| ABVD (28-day cycle) | ||

| Doxorubicin | 25 mg/m2 i.v. | Days 1 and 15 |

| Bleomycin | 10,000 iu/m2 i.v. | Days 1 and 15 |

| Vinblastine | 6 mg/m2 i.v. | Days 1 and 15 |

| Dacarbazine | 375 mg/m2 i.v. | Days 1 and 15 |

| BEACOPP escalated (21-day cycle)a | ||

| Bleomycin | 10,000 iu/m2 i.v. | Day 8 |

| Etoposide | 200 mg/m2 i.v. | Days 1–3 |

| Adriamycin (doxorubicin) | 35 mg/m2 i.v. | Day 1 |

| Cyclophosphamide | 1250 mg/m2 i.v. | Day 1 |

| Vincristine | 1.4 mg/m2 i.v. (max. 2 mg) | Day 8 |

| Procarbazine | 100 mg/m2 orally | Days 1–7 |

| Prednisolone | 40 mg/m2 orally | Days 1–14 |

| BEACOPP standard dose (21-day cycle)a | ||

| Bleomycin | 10,000 iu/m2 i.v. | Day 8 |

| Etoposide | 100 mg/m2 i.v. | Days 1–3 |

| Adriamycin (doxorubicin) | 25 mg/m2 i.v. | Day 1 |

| Cyclophosphamide | 650 mg/m2 i.v. | Day 1 |

| Vincristine | 1.4 mg/m2 i.v. (max. 2 mg) | Day 8 |

| Procarbazine | 100 mg/m2 orally | Days 1–7 |

| Prednisolone | 40 mg/m2 orally | Days 1–14 |

| ChlVPP | ||

| Chlorambucil | 6 mg/m2 orally | Days 1–14 |

| Vinblastine | 6 mg/m2 i.v. | Days 1 and 8 |

| Procarbazine | 100 mg/m2 orally | Days 1–14 |

| Prednisolone | 40 mg/m2 orally (max 60 mg) | Days 1–14 |

a Escalated BEACOPP and standard BEACOPP have shown activity in Hodgkin’s lymphoma, but their usage is not standard in the UK.

Salvage therapy for relapsed disease

Commonly used chemotherapy salvage regimens are listed in Table 51.2. If relapse occurs less than a year after treatment (early relapse), then high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell support should be considered. A patient who has never achieved complete remission (primary refractory disease) should receive high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell support.

Table 51.2 Salvage chemotherapy regimens effective in the treatment of lymphoma

| Regimen | Dose and route | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| DHAP | ||

| Cisplatin | 100 mg/m2 i.v. | Days 1 |

| Cytarabine | 2000 mg/m2 i.v. 12 hourly | Day 2 |

| Dexamethasone | 40 mg orally | Days 1–4 |

| ESHAP | ||

| Etoposide | 40 mg/m2 i.v. | Days 1–4 |

| Methylprednisolone | 500 mg/m2 i.v. | Days 1–5 |

| Cytarabine | 2000 mg/m2 i.v. | Day 1 |

| Cisplatin | 25 mg/m2 i.v. | Days 1–4 |

| ICE | ||

| Ifosfamide | 5000 mg/m2 i.v. | Day 2 |

| Carboplatina | AUC 5 i.v. | Day 2 |

| Etoposide | 100 mg/m2 i.v. | Days 1–3 |

| IVE | ||

| Epirubicin | 50 mg/m2 i.v. | Days 1 |

| Etoposide | 200 mg/m2 i.v. | Days 1–3 |

| Ifosfamide | 3000 mg/m2 i.v. | Days 1–3 |

AUC, area under the curve; GFR, glomerular filtration rate.

a Carboplatin dose (mg) = target AUC (mg/mL × min) × (GFR (mL/min) + 25).

High-dose chemotherapy plus autologous stem cell support is associated with a 40–50% 5-year survival rate. However, the significant toxicity of autologous stem cell transplantation means that it should be reserved for patients in whom there is a clear increase in chance of cure. Allogeneic transplant is an option in patients relapsing after autologous transplant (Brusamolino et al., 2009).

New agents

The anti-CD20 antibody rituximab has shown remission in 80% of cases of NLPHL, but due to short follow-up, its use is still considered experimental. Other monoclonal antibodies targeting CD30, which is expressed in the majority of classic HL cases, are being investigated. The most promising of these is a novel immunotoxin conjugate SGN-35 (Younes, 2009).

Gemcitabine has shown activity in relapsed classic HL with response rates up to 79% in a small series of heavily pretreated patients (Ng et al., 2005). Bortezomib and lenalidomide licensed for myeloma are also being investigated in those who have relapsed HL.

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

Histopathology and classification

There are two classification systems in common use. The Working formulation, developed in 1982, divides the lymphomas into low, intermediate and high grade. More recently, the revised European–American lymphoma (REAL) classification system has been developed (Table 51.3) and adopted by the World Health Organization (Box 51.3) to classify the grade of lymphoma. The REAL/WHO classification incorporates some diagnoses not included in the Working formulation and is a list of lymphomas using morphology, immunophenotype, genotype and clinical behaviour. It recognises the three major categories of lymphoid malignancies: B-cell neoplasms, T-cell/natural killer cell neoplasms and HL. However, in practice, the clinical behaviour of lymphomas informs the treatment strategies employed as these are based on the initial classification into indolent (low grade) or aggressive (intermediate and high grade) NHL. A more biologically relevant classification of lymphoma using the REAL/WHO classification and immunological and molecular characteristics increases the diagnostic specificity and improves selection and targeting of therapy.

Table 51.3 Clinical grade and frequency of lymphomas in the REAL classification

| Diagnosis | % of all cases |

|---|---|

| Indolent lymphomas | |

| Follicular lymphoma | 22 |

| Marginal zone B-cell, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue | 8 |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma | 7 |

| Marginal zone B-cell nodal | 2 |

| Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma | 1 |

| Aggressive lymphoma | |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | 31 |

| Mature (peripheral) T-cell lymphomas | 8 |

| Mantle cell lymphoma | 7 |

| Mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma | 2 |

| Anaplastic large cell lymphoma | 2 |

| Very aggressive lymphomas | |

| Burkitt’s lymphoma | 2 |

| Precursor T-lymphoblastic | 2 |

| Other lymphomas | 7 |

Staging

Determining the extent of disease in patients with NHL provides prognostic information and is useful in treatment planning. Patients with extensive disease usually require different therapy from those with limited disease. The NHLs can be staged according to the Ann Arbor classification (see Box 51.1). In this system, NHL is defined as stage I, II, III or IV, stage I being disease limited to a single lymph node and stage IV being advanced disease, with involvement of extralymphatic sites. The International Prognostic Index (Table 51.4) uses the following factors as predictors of poor prognosis: elevated LDH, stage III or IV disease, greater than 60 years of age, the higher the number of extranodal sites involved and the Eastern Co-operative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of two or higher. Other prognostic factors include bulky disease, presence of B symptoms and transformation from low- to high-grade disease. Prognostic indicators are important because they inform the treatment plan to avoid overtreating those with good prognosis and undertreating those with poor prognosis.

| Factor | Adverse prognosis |

|---|---|

| Age | ≥60 years |

| Ann Arbor stage | III or IV |

| Plasma lactate dehydrogenase level | Above normal |

| Number of extranodal sites of involvement | ≥2 |

| Performance status | ≥ECOG 2 or equivalent |

ECOG, Eastern Co-operative Oncology Group.

Treatment

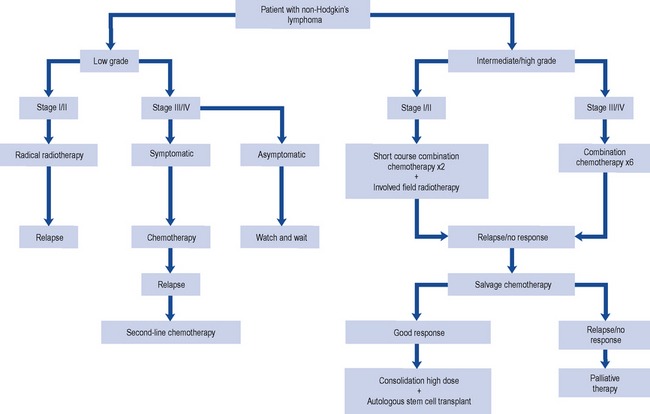

When designing a treatment plan for an individual patient, various factors must be taken into account. These include the patient’s age and general health, the extent or stage of the lymphoma and the particular histological subtype. Indolent (low-grade) lymphoma tends to run a slow course and although it is not curable, patients survive for prolonged periods with minimal symptoms. Aggressive (high-grade) lymphomas result in death within weeks or months if untreated. These lymphomas, however, are very responsive to chemotherapy and up to 50–60% may be cured with combination chemotherapy (Fig. 51.3).

Indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

The median age at which patients present with indolent NHLs is 50–60 years, and generally patients have a good performance status. If left untreated, indolent NHL has a comparatively long survival (median: 9 years). Follicular lymphoma is the most common of the indolent lymphomas. For the minority of patients presenting with limited-stage disease (stage I), radiotherapy to the involved field is generally used. However, the majority (80%) of patients present with advanced disease (stages II–IV) where the aim of treatment is to reduce disease bulk and offer symptom relief. Rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisolone (R-CVP) is used as the first-line treatment for advanced (stage III or IV) follicular lymphoma following the results of a study comparing R-CVP with CVP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisolone) (Marcus et al., 2005). This approach has been incorporated into national guidance (NICE, 2006). R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone) can also be used as first-line treatment for young patients with aggressive disease and is an option in relapsed disease (Table 51.5).

Table 51.5 Chemotherapy regimens effective in the treatment of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

| Drug | Dose and route | Day of administration |

|---|---|---|

| R-CHOP (21-day cycle) | ||

| Cyclophosphamide | 750 mg/m2 i.v. | Day 1 |

| Doxorubicin (hydroxydaunorubicin) | 50 mg/m2 i.v. | Day 1 |

| Vincristine (Oncovin) | 1.4 mg/m2 (max 2 mg) i.v. | Day 1 |

| Prednisolone | 100 mg orally | Days 1–5 |

| Rituximab | 375 mg/m2 i.v. | Day 1 |

| R-CVP (21-day cycle) | ||

| Cyclophosphamide | 750 mg/m2 i.v. | Day 1 |

| Vincristine (Oncovin) | 1.4 mg/m2 (max 2 mg) i.v. | Day 1 |

| Prednisolone | 100 mg orally | Days 1–5 |

| Rituximab | 375 mg/m2 i.v. | Day 1 |

| FC (28-day cycle) | ||

| Fludarabine | 40 mg/m2 orally | Days 1–3 |

| Cyclophosphamide | 250 mg/m2 daily orally | Days 1–3 |

| CHOP (21-day cycle) | ||

| Cyclophosphamide | 750 mg/m2 i.v. | Day 1 |

| Doxorubicin (hydroxydaunorubicin) | 50 mg/m2 i.v. | Day 1 |

| Vincristine (Oncovin) | 1.4 mg/m2 (max 2 mg) i.v. | Day 1 |

| Prednisolone | 100 mg orally | Days 1–5 |

Aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

The treatment for advanced-stage aggressive NHL is six cycles of the combination of R-CHOP chemotherapy (NICE, 2003). Doxorubicin can cause cardiotoxicity and patients with a reduced cardiac ejection fraction or co-morbidities may not tolerate R-CHOP. The use of gemcitabine (R-GCVP) is currently being investigated for this patient group as part of a clinical trial. The addition of bortezomib to R-CHOP in DLBCL is also being investigated as a clinical trial for patients with high-risk disease.

Relapsed aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

To induce a remission in patients with aggressive lymphoma and relapsed disease, it may be reasonable to use the same or similar regimen used for front-line chemotherapy. However, in most cases, the regimen chosen introduces new agents that are potentially not cross-resistant with those used in the initial treatment regimen. There are several salvage regimens in use and they generally have response rates of between 40% and 70%. Examples of salvage regimens are ICE (ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide), ESHAP (etoposide, methylprednisolone, cytarabine, cisplatin) and DHAP (cisplatin, cytarabine, dexamethasone) (see Table 51.2). Gemcitabine, a pyrimidine analogue, may be of benefit for patients with relapsed or refractory disease after two lines of treatment. Gemcitabine is used in combination with other agents, such as cisplatin and methylprednisolone. Rituximab can also be added to these salvage regimens. PBSCs are usually harvested after the second course of the salvage regimen. Patients then receive a high-dose regimen such as BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan) (Table 51.6) conditioning prior to stem cell infusion (autograft). Patients should only undergo an autograft if they have demonstrated a response to salvage chemotherapy.

Table 51.6 Conditioning chemotherapy for autologous transplantation

| Drug | Dose and route | Day of administration |

|---|---|---|

| BEAM | ||

| Carmustine | 300 mg/m2 i.v. | 6 days before reinfusion |

| Etoposide | 200 mg/m2 i.v. | 5–2 days before reinfusion |

| Cytarabine | 200 mg/m2 12 h i.v. | 5–2 days before reinfusion |

| Melphalan | 140 mg/m2 i.v. | 1 day before reinfusion |

| Reinfusion of stem cells | Day 0 | |

| LACE | ||

| Lomustine | 200 mg/m2 orally | 7 days before reinfusion |

| Etoposide | 1000 mg/m2 i.v. | 7 days before reinfusion |

| Cytarabine | 2000 mg/m2 | 6–5 days before reinfusion |

| Cyclophosphamide | 1800 mg/m2 i.v. | 4–2 days before reinfusion |

| Reinfusion of stem cells | Day 0 | |

Very aggressive lymphoma

There is an on-going debate about the value of adding rituximab to the CODOX-M/IVAC regimen.

Lymphoblastic lymphomas/leukaemia

Lymphoblastic lymphomas comprise about 2% of adult NHLs. Patients are often treated with the same regimens used in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL). Despite a very high rate of complete responders, long-term survival remains poor. Patients who fail after first-line chemotherapy have a long-term disease-free survival of less than 10%. These cases are subsequently treated as leukaemias (see Chapter 50).

Patient care

The chemotherapy regimens used to treat HL and NHL (see Tables 51.1 and 51.5) are usually administered on a hospital outpatient basis with the patient visiting the clinic regularly for assessment and treatment. The patient is monitored by FBCs carried out before each cycle of chemotherapy and at the ‘nadir’ between cycles. The nadir is when the blood count is at its lowest point, usually 10–14 days after the first day of chemotherapy. The interval between each cycle of chemotherapy enables normal body cells to recover before the patient receives further treatment. Disease response to treatment is monitored by repeating some of the diagnostic investigations, such as CT, at suitable intervals and the use of PET. If there is little or no response to treatment, a different chemotherapy regimen will be used or a decision made to withdraw from active therapy and provide optimum supportive care.

Counselling and support

The support available to the cancer patient, to help cope with both the illness and its treatment, has improved dramatically in recent years. Multidisciplinary teams working within specialised units have become skilled in anticipating the problems of lymphomas and their treatment. In addition, many charities provide care, support and advice such as Macmillan Cancer Support (www.macmillan.org.uk) and the Lymphoma Association (www.lymphoma.org.uk).

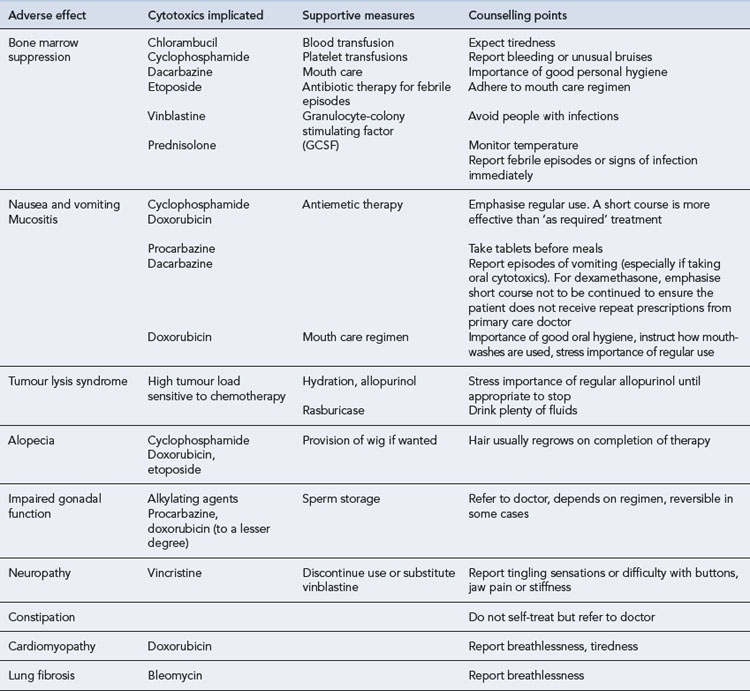

Supportive care

During a course of chemotherapy, the patient requires supportive care to minimise the adverse effects of treatment. The common adverse effects of the chemotherapy regimens discussed in this chapter are outlined in Table 51.7. These will occur to varying degrees depending on the combination of drugs and the doses used as well as individual patient factors.

Table 51.7 Adverse effects associated with chemotherapy regimens used in the lymphomas with supportive measures and counselling points

Nausea and vomiting

Nausea and vomiting is the most distressing and most feared adverse effect of chemotherapy. Its effect on the patient should not be underestimated, and its treatment is an important part of supportive care. The severity will depend on the combination of drugs used. For example, oral chlorambucil is generally well tolerated by almost all patients and requires no antiemetic cover. Regimens such as ABVD, which is highly emetic, will make most patients vomit if no antiemetics are given. Aprepitant, an NK1 receptor antagonist, is licensed for cisplatin chemotherapy regimens and may be useful for managing emesis with DHAP, ESHAP, etc. The patient should be counselled on the appropriate use of prescribed antiemetics (see Table 51.7).

Tumour lysis syndrome

Rasburicase can also be used to treat TLS but will only correct hyperuricaemia. Treatment of TLS should include vigorous hydration and diuresis. Historically alkaline diuresis has been recommended, but overzealous alkalinisation can lead to problems such as metabolic acidosis (Cairo and Bishop, 2004). Hypocalcaemia should be corrected if the patient is symptomatic, but this may increase calcium phosphate deposition. Hyperkalaemia and hyperphosphataemia should be corrected; patients may require haemofiltration or dialysis.

Growth factor support

Case 51.1

Mr RB is a 50-year-old man receiving a course of fludarabine and cyclophosphamide (see Table 51.5) for mantle cell lymphoma. He has no other medical problems and has normal renal and hepatic function.

Answers

Answers

Answers

Answers

American Society of Clinical Oncology. Guideline for antiemetics in oncology: update 2006. J. Clin. Oncol.. 2006;24:2932-2947.

Brusamolino E., Bacigalupo A., Barosi G. Classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma in adults: guidelines of the Italian Society of Hematology, the Italian Society of Experimental Hematology, and the Italian Group for Bone Marrow Transplantation on initial work-up, management, and follow-up. Haematologica. 2009;94:550-565.

Cairo M.S., Bishop M. Tumour lysis syndrome: new therapeutic strategies and classification. Br. J. Haematol.. 2004;127:3-11.

Department of Health. HSC 2008/001: Updated National Guidance on the Safe Administration of Intrathecal Chemotherapy. London: Department of Health. 2008. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Lettersandcirculars/Healthservicecirculars/DH_086870

Diehl V., Thomas R.K., Re D. Part II: Hodgkin’s lymphoma – diagnosis and treatment. Lancet Oncol.. 2004;5:19-26.

Engert A., Diehl V., Franklin J., et al. Escalated-dose BEACOPP in the treatment of patients with advanced-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma: 10 years of follow up of the GHSG HD9 Study. J. Clin. Oncol.. 2009;27:4548-4554.

Marcus R., Imrie K., Belch A., et al. CVP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CVP as first-line treatment for advanced follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2005;105:1417-1423.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Rituximab for Aggressive Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. London: NICE. 2003. Available at: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/TA65/Guidance/pdf/English

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Rituximab for the treatment of follicular lymphoma. London: NICE technology appraisal guidance A 110, NICE. 2006. Available at http://www.nice.org. uk/nicemedia/pdf/TA110guidance.pdf

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Rituximab for the treatment of relapsed or refractory stage III or IV follicular non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. London: NICE technology appraisal guidance 137, NICE. 2008. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/TA137guidance.pdf

Ng M., Waters J., Chau I., et al. Gemcitabine, cisplatin and methylprednisolone (GEM-P) is an effective salvage regimen in patients with relapsed and refractory lymphoma. Br. J. Cancer. 2005;92:1352-1357.

Souhami R., Tobias J., editors. Cancer and Its Management. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 1998.

Younes A. Novel treatment strategies for patients with relapsed classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Hematology (American Society Hematology Education Program). 2009:507-519.

UK Clinical Research Network Study Portfolio RATHL. A Randomized Phase III Trial to Assess Response Adapted Therapy Using FDG-PET Imaging in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Advanced Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Available at http://public.ukcrn.org.uk/search/StudyDetail.aspx?StudyID=4488, 2010.

West of Scotland Blood Cancer Network. Clinical Management Guidelines Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Version 3.0. Available at http://www.medednhsl.com/meded/clinicalgpp/pdf/WoSCAN_CMG_Hodgkins_v3_0_August_2009.pdf, 2009.

Dearden C., Matutes E. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Medicine. 2000;28:71-77.

Evens A.M., Winter J.N., Gordon L.I., et al. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. In Pazdur R., Coia L.R., Hoskins W.J., et al, editors: Cancer Management: A Multidisciplinary Approach, 13th ed, New York: PRR Melville, 2011. Available at: http://www.cancernetwork.com/cancermanagement-12

Laport G.F., Williams S.F. The role of high-dose chemotherapy in patients with Hodgkin’s disease and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Semin. Oncol.. 1998;25:503-517.

Leonard J.P., Coleman M., editors. Hodgkin’s and Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2006.

Yahalom J., Strauss D. Hodgkin’s lymphoma. In Pazdur R., Coia L.R., Hoskins W.J., et al, editors: Cancer Management: A Multidisciplinary Approach, 13th ed, New York: PRR Melville, 2011. Available at http://www.cancernetwork.com/cancer-management-12

Provan D., Singer C.R.J., Baglin T., et al. Oxford Handbook of Clinical Haematology, third ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2009.