Chapter 18 Lymph Nodes

A. General Considerations

6 Where should you look for enlarged nodes?

8 What is the differential diagnosis of a generalizedadenopathy?

One of three processes: (1) a disseminated malignancy, especially hematologic (lymphomas, leukemias, and angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy); (2) a collagen vascular disorder (sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE]); or (3) an infectious process (mononucleosis, cytomegalovirus [CMV], AIDS, toxoplasmosis, syphilis, tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, brucellosis, and bubonic plague). Drug reaction can do it, too, and so can intravenous abuse. Some medications (e.g., phenytoin) specifically cause lymphadenopathy; others (e.g., cephalosporins, penicillins, or sulfonamides) do it instead in the context of a serum sickness-like syndrome, with fever, arthralgias, and skin rash (see Table 18-1).

| Allopurinol (Zyloprim) | Penicillin |

| Atenolol (Tenormin) | Phenytoin (Dilantin) |

| Captopril (Capozide) | Primidone (Mysoline) |

| Carbamazepine (Tegretol) | Pyrimethamine (Daraprim) |

| Cephalosporins | Quinidine |

| Gold | Sulfonamides |

| Hydralazine (Apresoline) | Sulindac (Clinoril) |

(Adapted from Ferrer R: Lymphadenopathy. Am Fam Physician 58:1313–1323, 1998.)

12 Should one know the regions drained by the various lymphonodal stations?

Yes, since this may unlock the underlying cause. After detecting an enlarged node, always examine the region drained by it (see Table 18-2). Look for infections, skin lesions, or tumors.

Table 18-2 Lymph Node Groups: Location, Lymphatic Drainage and Selected Differential Diagnosis*

| Location | Lymphatic Drainage | Causes |

|---|---|---|

| Submental | Lower lip, anterior floor of mouth, tip of tongue, skin of cheek, teeth, nose | Mononucleosis-like syndromes, Epstein-Barr virus, CMV, toxoplasmosis |

| Submandibular | Tongue, submaxillary gland, lips and mouth, conjunctivae | Infections of head, neck, sinuses, ears, eyes, scalp, pharynx |

| Anterior cervical (jugular) | Tongue, tonsil, pinna, parotid, larynx, thryroid, upper esophagus | Pharyngitis organisms, rubella, upper respiratory infections, cancer of tongue, larynx, thyroid and cervical esophagus |

| Posterior cervical | Scalp and neck, middle ear, skin of arms and pectorals, thorax, cervical and axillary nodes | Mononucleosis, toxoplasmosis, tuberculosis, rubella, otitis media, scalp infections and dandruff, Kikuchi’s disease, lymphoma, head and neck malignancy |

| Preauricular | Eyelids and conjunctivae, temporal region, pinna | Disease external auditory canal, ipsilateral conjunctivitis (Parinaud’s syndrome), lymphoma |

| Postauricular | External auditory meatus, pinna, scalp | Local infection, but also rubella |

| Occipital | Scalp and head | Local infection |

| Right supraclavicular node | Breast, lungs, esophagus mediastinum, | Lung, breast, mediastinum |

| Left supraclavicular node | Breast, lungs, abdomen via thoracic duct, and pelvis | Lymphoma, thoracic, retroperitoneal, gastrointestinal or pelvic cancer, bacterial or fungal infection |

| Axillary | Arm, thoracic wall, breast | Arm infections, cat-scratch disease, tularemia, lymphoma, breast cancer, silicone implants, brucellosis, melanoma |

| Epitrochlear | Ulnar aspect of forearm and hand | Infections, lymphoma, sarcoidosis and connective tissue diseases, tularemia, secondary syphilis, leprosy, leishmaniasis, rubella |

| Inguinal | Penis, scrotum, vulva, vagina, perineum, gluteal region, lower abdominal wall, lower anal canal, extremities (benign reactive in shoeless walkers) | Infections of the leg or foot, STDs (e.g., herpes simplex virus, gonococcal infection, syphilis, chancroid, granuloma inguinale, lymphogranuloma venereum), lymphoma, pelvic malignancy, bubonic plague |

STDs = sexually transmitted diseases.

* Modified from Ferrer R: Lymphadenopathy. Am Fam Physician 58:1313–1323, 1998.

14 Why does the patient’s age help?

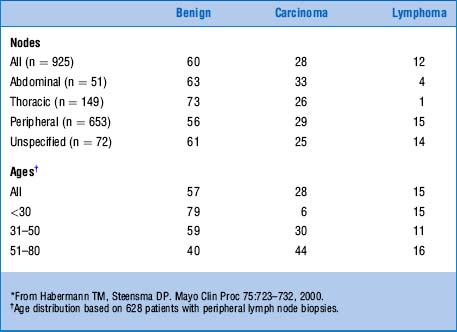

Because it is the most important predictor of malignancy. Although lymphoproliferative disorders also may affect younger individuals, neoplastic nodes are usually more common in those older than 40 years (Table 18-3). Yet some malignant-looking nodes may actually be benign. Infectious mononucleosis, for example, may often resemble Hodgkin’s disease.

15 What about associated signs and symptoms?

They can be “local” or systemic (Table 18-4). Local findings suggest infection or neoplasm in a specific site (like the swollen nodes and lymphangitic streaks of a skin infection). Conversely, systemic symptoms (such as fever, fatigue, night sweats, and unexplained weight loss) argue in favor of a collagen vascular, lymphoproliferative, or infectious disorder (e.g., tuberculosis [TB]). Still, lack of associated signs or symptoms does not exclude malignancy and thus should not stop a work-up. Finally, remember that the adenopathy of Hodgkin’s disease may become painful after alcohol ingestion.

| Disorder | Associated Findings |

|---|---|

| Common Causes of Lymphadenopathy | |

| Mononucleosis-type syndromes | Fatigue, malaise, fever, atypical lymphocytosis |

| Epstein-Barr virus* | Splenomegaly in 50% |

| Toxoplasmosis* | 80–90% asymptomatic |

| Cytomegalovirus* | Often mild symptoms; patients may have hepatitis |

| Initial stages of HIV infection* | “Flu-like” illness, rash |

| Cat-scratch disease | Fever in 30%; cervical or axillary nodes |

| Pharyngitis (group A Streptococcus, gonococcus) | Fever, pharyngeal exudates, cervical nodes |

| Tuberculosis lymphadenitis* | Painless, matted cervical nodes |

| Secondary syphilis* | Rash |

| Hepatitis B* | Fever, nausea, vomiting, icterus |

| Lymphogranuloma venereum | Tender, matted inguinal nodes |

| Chancroid | Painful ulcer, painful inguinal nodes |

| Lupus erythematosus* | Arthritis, rash, serositis; renal, neurologic, hematologic disorders |

| Rheumatoid arthritis* | Arthritis |

| Lymphoma* | Fever, night sweats, weight loss in 20–30% |

| Leukemia* | Blood dyscrasias, bruising |

| Serum sickness* | Fever, malaise, arthralgia, urticaria; exposure to antisera or medications |

| Sarcoidosis | Hilar nodes, skin lesions, dyspnea |

| Kawasaki disease* | Fever, conjunctivitis, rash, mucosal lesions |

| Less Common Causes of Lymphadenopathy | |

| Lyme disease* | Rash, arthritis |

| Measles* | Fever, conjunctivitis, rash, cough |

| Rubella* | Rash |

| Tularemia* | Fever, ulcer at inoculation site |

| Brucellosis* | Fever, sweats, malaise |

| Plague | Febrile, acutely ill with cluster of tender nodes |

| Typhoid fever* | Fever, chills, headache, abdominal complaints |

| Still’s disease* | Fever, rash, arthritis |

| Dermatomyositis* | Proximal weakness, skin changes |

| Amyloidosis* | Fatigue, weight loss |

* Causes of generalized lymphadenopathy.

(Adapted from Ferrer R: Lymphadenopathy. Am Fam Physician 58:1313–1323, 1998.)

18 Are there any epidemiologic clues that might narrow the differential diagnosis?

Yes. Occupational exposure, recent travel, or high-risk behavior may all contribute (Table 18-5).

Table 18-5 Epidemiologic Clues to the Diagnosis of Lymphadenopathy

| Exposure | Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| General | |

| Cat | Cat-scratch disease, toxoplasmosis |

| Undercooked meat | Toxoplasmosis |

| Tick bite | Lyme disease, tularemia |

| Tuberculosis | Tuberculous adenitis |

| Recent blood transfusion or transplant | Cytomegalovirus, HIV |

| High-risk sexual behavior | HIV, syphilis, herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, hepatitis B infection |

| Intravenous drug use | HIV, endocarditis, hepatitis B infection |

| Occupational | |

| Hunters, trappers | Tularemia |

| Fishermen, fishmongers, slaughterhouse workers | Erysipeloid |

| Travel-related | |

| Arizona, southern California, New Mexico, western Texas | Coccidioidomycosis |

| Southwestern United States | Bubonic plague |

| Southeastern or central United States | Histoplasmosis |

| Southeast Asia, India, Central or West Africa | Scrub typhus |

| Central or West Africa | African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness) |

| Central or South America | American trypanosomiasis (Chagas’ disease) |

| East Africa, Mediterranean, China, Latin America | Kala-azar (leishmaniasis) |

| Mexico, Peru, Chile, India, Pakistan, Egypt, Indonesia | Typhoid fever |

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus.

(Adapted from Ferrer R: Lymphadenopathy. Am Fam Physician 58:1313–1323, 1998.)

19 Which node characteristics can be clinically helpful?

In addition to location, six features may help the diagnosis:

Size: This is easily measured by a plastic caliper or ruler. It can predict its nature and guide biopsy. Although there is no “normal” size (since this depends on age and background antigenic exposure), some authors have defined the upper limits of normal as a node >1 cm that has been present outside the inguinal region for more than 1 month. Yet, inguinal nodes can be normal up to 1.5 cm, whereas preauricular and epitrochlear nodes are suspicious even if 0.5–1 cm. Moreover, large but benign nodes are quite common in IV drug users. In fact, some authors have even suggested raising the threshold of suspicion to 1.5 × 1.5 cm. Finally, although no specific diagnosis can be based on size, some valuable predictions can be inferred. For example, in 213 adults with unexplained lymphadenopathy, nodes <1 cm were never neoplastic. Conversely, cancer was the final diagnosis in 8% of 1–1.5 cm nodes and 38% of >1.5 cm. In children, nodes >2 cm (along with an abnormal chest x-ray and absence of ear, nose, and throat symptoms) argue in favor of granulomatous diseases (TB, cat-scratch disease, sarcoid) or cancer (mostly lymphomas).

Size: This is easily measured by a plastic caliper or ruler. It can predict its nature and guide biopsy. Although there is no “normal” size (since this depends on age and background antigenic exposure), some authors have defined the upper limits of normal as a node >1 cm that has been present outside the inguinal region for more than 1 month. Yet, inguinal nodes can be normal up to 1.5 cm, whereas preauricular and epitrochlear nodes are suspicious even if 0.5–1 cm. Moreover, large but benign nodes are quite common in IV drug users. In fact, some authors have even suggested raising the threshold of suspicion to 1.5 × 1.5 cm. Finally, although no specific diagnosis can be based on size, some valuable predictions can be inferred. For example, in 213 adults with unexplained lymphadenopathy, nodes <1 cm were never neoplastic. Conversely, cancer was the final diagnosis in 8% of 1–1.5 cm nodes and 38% of >1.5 cm. In children, nodes >2 cm (along with an abnormal chest x-ray and absence of ear, nose, and throat symptoms) argue in favor of granulomatous diseases (TB, cat-scratch disease, sarcoid) or cancer (mostly lymphomas).

Duration: The longer the node has been present, the less its risk of being neoplastic or granulomatous. Still, lymphomatous nodes can regress, albeit temporarily.

Duration: The longer the node has been present, the less its risk of being neoplastic or granulomatous. Still, lymphomatous nodes can regress, albeit temporarily.

Consistency: Soft nodes are usually infectious or inflammatory, whereas rock-hard ones tend to be neoplastic, often metastatic. Exceptions include the nodes of Hodgkin’s, which are firm but rubbery. Fluctuant nodes reflect instead bacterial lymphadenitis with necrosis. They feel like a tense balloon or grape, are typically tender, and may even fistulize through the skin, forming open sinuses that are a common feature in TB. Nodes of this type, especially in groins or axillae, are often referred to as buboes (from the Greek term for swollen groin) and used to be typical of infectious processes, such as gonorrhea, syphilis, TB, and, of course, the “bubonic” plague of old.

Consistency: Soft nodes are usually infectious or inflammatory, whereas rock-hard ones tend to be neoplastic, often metastatic. Exceptions include the nodes of Hodgkin’s, which are firm but rubbery. Fluctuant nodes reflect instead bacterial lymphadenitis with necrosis. They feel like a tense balloon or grape, are typically tender, and may even fistulize through the skin, forming open sinuses that are a common feature in TB. Nodes of this type, especially in groins or axillae, are often referred to as buboes (from the Greek term for swollen groin) and used to be typical of infectious processes, such as gonorrhea, syphilis, TB, and, of course, the “bubonic” plague of old.

Matting: Fusion into a scalloped mass transforms individual nodes into large conglomerates. This is usually a neoplastic feature (metastatic carcinoma or lymphomas), but also can occur in inflammatory processes (like sarcoid) and chronic infections (like TB and lymphogranuloma venereum).

Matting: Fusion into a scalloped mass transforms individual nodes into large conglomerates. This is usually a neoplastic feature (metastatic carcinoma or lymphomas), but also can occur in inflammatory processes (like sarcoid) and chronic infections (like TB and lymphogranuloma venereum).

Relationship to surrounding tissues: Adherence to overlying skin, subjacent tissues, or both does not separate inflammation from neoplasm but does exclude benignity.

Relationship to surrounding tissues: Adherence to overlying skin, subjacent tissues, or both does not separate inflammation from neoplasm but does exclude benignity.

Pain/tenderness: This reflects rapid growth with painful capsular stretching. It is a sign of suppurative inflammation but also may reflect hemorrhage into the necrotic center of a rapidly expanding neoplastic node. Hence, tenderness does not reliably differentiate benign from malignant ones. The same applies to sinus tract formation, which can occur in infections (actinomycosis and TB) as well as cancer.

Pain/tenderness: This reflects rapid growth with painful capsular stretching. It is a sign of suppurative inflammation but also may reflect hemorrhage into the necrotic center of a rapidly expanding neoplastic node. Hence, tenderness does not reliably differentiate benign from malignant ones. The same applies to sinus tract formation, which can occur in infections (actinomycosis and TB) as well as cancer.

20 What is the best way to deal with adenopathy?

Start with history and physical exam (H&P), since they can often identify the etiology (upper respiratory infection [URI], pharyngitis, periodontal disease, conjunctivitis, insect bites, focal infection, recent immunization, cat-scratch disease, tinea, or dermatitis), thus preempting the need for further work-up.

Start with history and physical exam (H&P), since they can often identify the etiology (upper respiratory infection [URI], pharyngitis, periodontal disease, conjunctivitis, insect bites, focal infection, recent immunization, cat-scratch disease, tinea, or dermatitis), thus preempting the need for further work-up.

H&P also can offer a presumptive diagnosis and guide the work-up (EBV, HIV, lymphoma,syphilis).

H&P also can offer a presumptive diagnosis and guide the work-up (EBV, HIV, lymphoma,syphilis).

Once the initial evaluation is complete, some patients may still have either unexplained lymphadenopathy or a presumptive diagnosis unconfirmed by labs and clinical course. In this case, if the adenopathy is localized (and the clinical picture is reassuring [i.e.,a benign history, an unremarkable exam, and no constitutional symptoms]), allow 3–4 weeks of observation before resorting to biopsy. If the clinical picture is instead worrisome (risk factors for malignancy, constitutional signs/symptoms) or the lymphadenopathy is generalized, do further testing and get a biopsy. Still, avoid biopsy in patients with probable viral illness, since their pathology may simulate lymphoma.

Once the initial evaluation is complete, some patients may still have either unexplained lymphadenopathy or a presumptive diagnosis unconfirmed by labs and clinical course. In this case, if the adenopathy is localized (and the clinical picture is reassuring [i.e.,a benign history, an unremarkable exam, and no constitutional symptoms]), allow 3–4 weeks of observation before resorting to biopsy. If the clinical picture is instead worrisome (risk factors for malignancy, constitutional signs/symptoms) or the lymphadenopathy is generalized, do further testing and get a biopsy. Still, avoid biopsy in patients with probable viral illness, since their pathology may simulate lymphoma.

22 What is the differential diagnosis of an unexplained lymphadenopathy?

C = Cancers: hematologic malignancies (Hodgkin’s disease, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, acute and chronic leukemia, Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia, multiple myeloma [uncommon], systemic mastocytosis) and metastatic “solid” tumors (breast, lung, renal cell, prostate, other)

C = Cancers: hematologic malignancies (Hodgkin’s disease, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, acute and chronic leukemia, Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia, multiple myeloma [uncommon], systemic mastocytosis) and metastatic “solid” tumors (breast, lung, renal cell, prostate, other)

H = Hypersensitivity syndromes: serum sickness, drug sensitivity (diphenylhydantoin, carbamazepine, primidone, gold, allopurinol, indomethacin, sulfonamides, others), silicone reaction, vaccination-related, and graft versus host disease

H = Hypersensitivity syndromes: serum sickness, drug sensitivity (diphenylhydantoin, carbamazepine, primidone, gold, allopurinol, indomethacin, sulfonamides, others), silicone reaction, vaccination-related, and graft versus host disease

I = Infections: viral (infectious mononucleosis [Epstein-Barr virus], cytomegalovirus, infectious hepatitis, postvaccinal lymphadenitis, adenovirus, herpes zoster, HIV/AIDS, human T-lymphocyte virus 1), bacterial (cutaneous infections [staphylococci, streptococci], cat-scratch fever, chancroid, melioidosis, TB, atypical mycobacteria, primary and secondary syphilis), chlamydial (lymphogranuloma venereum), protozoan (toxoplasmosis), mycotic (histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis), rickettsial (scrub typhus), helminthic (filariasis)

I = Infections: viral (infectious mononucleosis [Epstein-Barr virus], cytomegalovirus, infectious hepatitis, postvaccinal lymphadenitis, adenovirus, herpes zoster, HIV/AIDS, human T-lymphocyte virus 1), bacterial (cutaneous infections [staphylococci, streptococci], cat-scratch fever, chancroid, melioidosis, TB, atypical mycobacteria, primary and secondary syphilis), chlamydial (lymphogranuloma venereum), protozoan (toxoplasmosis), mycotic (histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis), rickettsial (scrub typhus), helminthic (filariasis)

C = Connective tissue disorders: rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, mixed connective tissue disease, Sjögren syndrome

C = Connective tissue disorders: rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, mixed connective tissue disease, Sjögren syndrome

A = Atypical lymphoproliferative disorders: angiofollicular (giant) lymph node hyperplasia (Castleman disease), angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia, angiocentric immunoproliferative disorders, lymphomatoid granulomatosis, Wegener granulomatosis

A = Atypical lymphoproliferative disorders: angiofollicular (giant) lymph node hyperplasia (Castleman disease), angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia, angiocentric immunoproliferative disorders, lymphomatoid granulomatosis, Wegener granulomatosis

G = Granulomatous lesions: TB, histoplasmosis, mycobacterial infections, cryptococci, silicosis, berylliosis, cat-scratch fever

G = Granulomatous lesions: TB, histoplasmosis, mycobacterial infections, cryptococci, silicosis, berylliosis, cat-scratch fever

O = Other unusual causes of lymphadenopathy: inflammatory pseudotumor of lymph nodes, histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis (Kikuchi lymphadenitis), sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease), vascular transformation of sinuses, progressive transformation of germinal centers

O = Other unusual causes of lymphadenopathy: inflammatory pseudotumor of lymph nodes, histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis (Kikuchi lymphadenitis), sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease), vascular transformation of sinuses, progressive transformation of germinal centers

23 Which clinical presentations may help identify the cause of lymphadenopathy?

Mononucleosis-type syndromes: Adenopathy plus fatigue, malaise, fever, and increased atypical lymphocyte count. Differential diagnosis includes Epstein-Barr virus (mononucleosis), toxoplasmosis, CMV, streptococcal pharyngitis, hepatitis B, and acute HIV.

Mononucleosis-type syndromes: Adenopathy plus fatigue, malaise, fever, and increased atypical lymphocyte count. Differential diagnosis includes Epstein-Barr virus (mononucleosis), toxoplasmosis, CMV, streptococcal pharyngitis, hepatitis B, and acute HIV.

HIV infection: Any persistent generalized lymphadenopathy (i.e., one of at least 3 months’ duration, involving two extrainguinal sites or more) should suggest an early stage of HIV infection. Generalized adenopathy in HIV suggests Kaposi, CMV, toxoplasmosis, TB, cryptococcosis, syphilis, and lymphoma.

HIV infection: Any persistent generalized lymphadenopathy (i.e., one of at least 3 months’ duration, involving two extrainguinal sites or more) should suggest an early stage of HIV infection. Generalized adenopathy in HIV suggests Kaposi, CMV, toxoplasmosis, TB, cryptococcosis, syphilis, and lymphoma.

Ulceroglandular syndrome: Regional adenopathy plus skin lesions. The classic cause is tularemia, acquired by contact with an infected rabbit or tick. More common, however, are streptococcal infection (impetigo) and cat-scratch and Lyme diseases.

Ulceroglandular syndrome: Regional adenopathy plus skin lesions. The classic cause is tularemia, acquired by contact with an infected rabbit or tick. More common, however, are streptococcal infection (impetigo) and cat-scratch and Lyme diseases.

Oculoglandular syndrome: Preauricular adenopathy with conjunctivitis. Common causes include viral keratoconjunctivitis and cat-scratch disease from ocular lesions.

Oculoglandular syndrome: Preauricular adenopathy with conjunctivitis. Common causes include viral keratoconjunctivitis and cat-scratch disease from ocular lesions.

B. Cervical and Supraclavicular Nodes

25 What are the important head and neck stations?

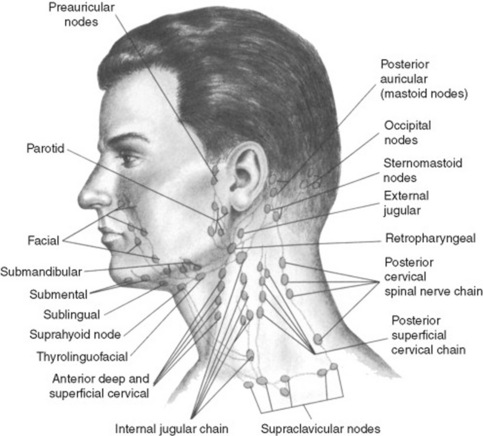

There is a fair amount of variability and overlap in pathways of drainage (Fig. 18-1). Overall, you should examine nodes in the following order:

Submental: Just below the chin. They drain the teeth and intra-oral cavity.

Submental: Just below the chin. They drain the teeth and intra-oral cavity.

Submandibular: Along the underside of the jaw, on either side. They drain the structures in the posterior floor of the mouth.

Submandibular: Along the underside of the jaw, on either side. They drain the structures in the posterior floor of the mouth.

Anterior cervical (both superficial and deep): Also called “jugular chain nodes,” these lie on top of and beneath the sternocleidomastoid muscles (SCM) on either side of the neck, from the angle of the jaw to the top of the clavicle (the SCMs allow the head to rotate to the opposite side and can be easily identified by asking the patient to turn the head). They drain the internal structures of the throat as well as part of the posterior pharynx, tonsils, and thyroid gland.

Anterior cervical (both superficial and deep): Also called “jugular chain nodes,” these lie on top of and beneath the sternocleidomastoid muscles (SCM) on either side of the neck, from the angle of the jaw to the top of the clavicle (the SCMs allow the head to rotate to the opposite side and can be easily identified by asking the patient to turn the head). They drain the internal structures of the throat as well as part of the posterior pharynx, tonsils, and thyroid gland.

Posterior cervical: Also called “posterior triangle nodes,” these extend in a line posterior to the SCMs, but in front of the trapezius, from the mastoid bone to the clavicle. They drain the skin on the back of the head and are frequently enlarged during upper respiratory infections (mononucleosis).

Posterior cervical: Also called “posterior triangle nodes,” these extend in a line posterior to the SCMs, but in front of the trapezius, from the mastoid bone to the clavicle. They drain the skin on the back of the head and are frequently enlarged during upper respiratory infections (mononucleosis).

Tonsillar: Just below the angle of the mandible. They drain the tonsillar and posterior pharyngeal regions.

Tonsillar: Just below the angle of the mandible. They drain the tonsillar and posterior pharyngeal regions.

Preauricular and postauricular: Respectively, anterior and posterior to the ear. Swelling of the pre-auricular node in a setting of conjunctivitis-like “pink eye” represents Parinaud’s (oculoglandular) syndrome, occurring in various conditions, including Tularemia and Catscratch disease (Bartonellosis).

Preauricular and postauricular: Respectively, anterior and posterior to the ear. Swelling of the pre-auricular node in a setting of conjunctivitis-like “pink eye” represents Parinaud’s (oculoglandular) syndrome, occurring in various conditions, including Tularemia and Catscratch disease (Bartonellosis).

Occipital:Common in childhood infections, but rare in adults—except in a setting of either banal scalp infection or, more ominously, generalized lymphadenopathy from systemic disease (HIV).

Occipital:Common in childhood infections, but rare in adults—except in a setting of either banal scalp infection or, more ominously, generalized lymphadenopathy from systemic disease (HIV).

Supraclavicular: In the hollow above the clavicle, just lateral to where it joins the sternum. They drain part of the thoracic cavity and abdomen (see questions 31–36).

Supraclavicular: In the hollow above the clavicle, just lateral to where it joins the sternum. They drain part of the thoracic cavity and abdomen (see questions 31–36).

26 And so, what is the overall significance of cervical lymphadenopathy?

It depends on location, but may suggest either infection or malignancy.

30 What are Delphian nodes?

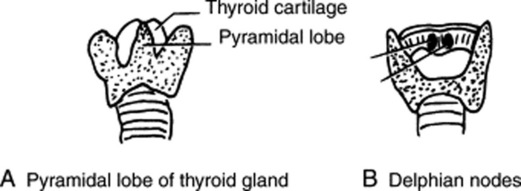

A cluster of small and midline prelaryngeal nodes (Fig. 18-2). These are typically located on the thyrohyoid membrane—just anterior to the cricothyroid ligament, and just above the thyroid isthmus. Given their pretracheal and superficial location, they are easily palpable if enlarged, even though at times they may be confused with the pyramidal lobe of the gland. They drain the thyroid and larynx, and like Delphi in ancient Greece, they have traditionally been considered an oracle—of thyroid disease or laryngeal malignancy (even though objective supportive data are lacking). They also are the first to be exposed during surgery, thus foretelling the nature of the underlying illness. Delphian nodes reflect a range of thyroid involvement, including subacute thyroiditis, Hashimoto’s, and thyroid cancer. If due to laryngeal carcinoma, they give the disease a more ominous connotation.

31 What is the clinical significance of a palpable supraclavicular node?

Right supraclavicular nodes usually indicate metastatic involvement from ipsilateral breast or lung (but also mediastinum and esophagus). Because of bilateral crossed drainage, a right node also may reflect lung cancer of the left lower lobe.

Right supraclavicular nodes usually indicate metastatic involvement from ipsilateral breast or lung (but also mediastinum and esophagus). Because of bilateral crossed drainage, a right node also may reflect lung cancer of the left lower lobe.

Left supraclavicular nodes have instead a much wider differential diagnosis, since the left supraclavicular fossa not only drains the thorax, but also various abdominal and pelvic sites. Hence, it functions as a sentinel for distant metastases.

Left supraclavicular nodes have instead a much wider differential diagnosis, since the left supraclavicular fossa not only drains the thorax, but also various abdominal and pelvic sites. Hence, it functions as a sentinel for distant metastases.

C. Upper Extremity Nodes

37 What is the best way to search for axillary nodes?

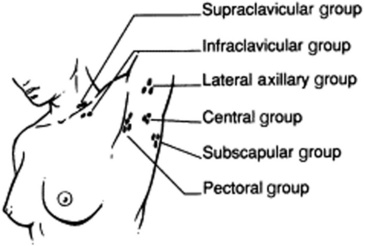

For the left axilla, grasp the patient’s left wrist or elbow with your left hand, and lift the arm up and out laterally. Then use the tip of your right fingers to palpate deep into the axillary fossa and roof. Do this first with the patient’s arm gently relaxed and passively abducted from the chest wall. Then repeat it with the arm passively and gently adducted. Examine the right axilla in a similar fashion, albeit with a reversed hand positioning. This technique allows the patient’s arm to remain completely relaxed, thus minimizing any tension in the surrounding tissues that could otherwise mask enlarged lymph nodes. It also is easy to carry out on the supine patient, very much as it would be if it were linked with the female breast exam (Fig 18-3).

D. Lower Extremity Nodes

E. Abdominal Nodes

45 What is Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule?

A periumbilical node or hard mass of the navel. It is clinically quite valuable since it represents a direct or lymphonodal metastasis from an intrapelvic/intra-abdominal tumor. The finding was first reported by William J. Mayo in 1928, based on observations by his scrub nurse, Sister Mary Joseph of St. Mary’s Hospital, who could predict laparotomy findings by feeling a periumbilical mass while scrubbing the patient’s abdomen. This is not surprising since the umbilicus is highly susceptible to intra-abdominal metastases, thanks to its multiple anatomic relations and generous vascular/embryologic connections. In fact, in 20% of cases, umbilical metastasis is the presenting manifestation. A total of 407 reports have been published. The usual type is an adenocarcinoma, with the stomach being the most common primary site (23%), followed by ovary (16%), large bowel (10–14%), and pancreas (7–11%). Overall, 52% of cancers are gastrointestinal in origin, and 28% gynecologic; 15% are of unknown primary, and 3% originate instead from the thoracic cavity. In 14–33% of cases, umbilical metastasis is the first (and diagnostic) manifestation of a previously occult neoplasm. In 40%, the nodule is instead an early sign of relapse in a patient with known cancer. Overall, a Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule is a bad omen, since survival is less than 1 year (see also Chapter 15, The Abdomen, question 7).

1 Allhiser JN, McKnight TA, McKnight TA, Shank JC, et al. Lymphadenopathy in a family practice. J Fam Pract. 1981;12:27-32.

2 Benson JR, Singh S, Thomas JM. Sister Joseph’s nodule: A case report and review. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1997;23:451-454.

3 Crook LD, Tempest B. Plague: A clinical review of 27 cases. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:1253-1256.

4 Dawson PJ, Cooper RA, Rambo ON. Diagnosis of malignant lymphoma: A clinicopathological analysis of 158 different lymph node biopsies. Cancer. 1964;17:1405-1413.

5 De Vriese AS, Philippe J, Van Renterghem, DM, et al. Carbamazepine hypersensitivity syndrome: Report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1995;74:144-151.

6 Ferrer R. Lymphadenopathy. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58:1313-1323.

7 Fessas P, Pangalis G. Non-malignant lymphadenopathies: Reactive non-specific and reactive specific. In: Pangalis GA, Polliack A, editors. Benign and Malignant Lymphadenopathies: Clinical and Laboratory Diagnosis. Chur, Switzerland: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1993:31-45.

8 Fijten GH, Blijham GH. Unexplained lymphadenopathy in family practice. An evaluation of the probability of malignant causes and the effectiveness of physicians’ work-up. J Fam Pract. 1988;27:373-376.

9 Habermann TM, Steensma DP. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2000;75:723-732.

10 Hartsock RJ, Halling LW, King FM. Luetic lymphadenitis: A clinical and histologic study of 20 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1970;53:304-314.

11 Hartsock RJ. Postvaccinial lymphadenitis: Hyperplasia of lymphoid tissue that simulates malignant lymphomas. Cancer. 1968;21:632-649.

12 Sapira JD: The Art and Science of Bedside Diagnosis: Baltimore, Williams and Wilkins. ed 1. 1990