Chapter 214 Lyme Disease (Borrelia burgdorferi)

Epidemiology

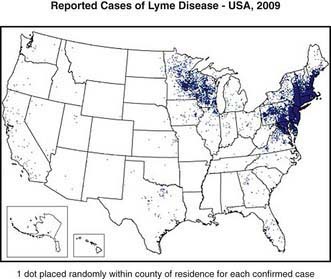

Lyme disease has been reported from >50 countries. In the USA approximately 20,000 cases were reported in 2006; however, because of incomplete reporting of cases, it is estimated that the actual number of cases is much higher. From 1992 through 2006, 93% of cases occurred in 10 states: Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Wisconsin (Fig. 214-1). In endemic areas, the reported annual incidence ranges from 20 to 100 cases/100,000 population, although this figure may be as high as 600 cases/100,000 population in hyperendemic areas. In Europe, most cases occur in the Scandinavian countries and in central Europe, especially Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. The reported incidence is highest among children 5-9 yr of age, with a second peak of disease activity in middle-aged adults. In the USA, Lyme disease is diagnosed in boys slightly more often than in girls, and 94% of patients are of European descent. Early Lyme disease (described later) usually occurs from spring to early fall, corresponding to deer tick activity. Late disease (chiefly arthritis) occurs year round. Among adults, outdoor occupation and leisure activities are risk factors; for children, location of residence in an endemic area is the most important risk for infection.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations of Lyme disease are divided into early and late stages (Table 214-1). Early Lyme disease is further classified as early localized or early disseminated disease. Untreated patients can progressively develop clinical symptoms of each stage of the disease, or they can present with early disseminated or with late disease without apparently having had any symptoms of the earlier stages of Lyme disease.

| DISEASE STAGE | TIMING AFTER TICK BITE | TYPICAL CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS |

|---|---|---|

| Early localized | 3-30 days | EM (single), variable constitutional symptoms (headache, fever, myalgia, arthralgia, fatigue) |

| Early disseminated | 3-12 wk | EM (single or multiple), worse constitutional symptoms, cranial neuritis, meningitis, carditis, ocular disease |

| Late | >2 mo | Arthritis |

EM, erythema migrans.

Early Localized Disease

The first clinical manifestation of Lyme disease in most patients is erythema migrans (Fig. 214-2). Although it usually occurs 7-14 days after the bite, the onset of the rash has been reported from 3 to 30 days later. The initial lesion occurs at the site of the bite. The rash is generally either uniformly erythematous or a target lesion with central clearing; rarely, there are vesicular or necrotic areas in the center of the rash. Occasionally the rash is itchy or painful, though usually it is asymptomatic. The lesion can occur anywhere on the body, although the most common locations are the axilla, periumbilical area, thigh, and groin. It is not unusual for the rash to occur on the neck or face, especially in young children. Without treatment, the rash gradually expands (hence the name migrans) to an average diameter of 15 cm and typically remains present for 1-2 wk. Erythema migrans may be associated with systemic features, including fever, myalgia, headache, or malaise. Co-infection with Babesia microti or Anaplasma phagocytophilum during early infection with B. burgdorferi is associated with more severe systemic symptoms.

Early Disseminated Disease

In the USA, about 20% of patients with acute B. burgdorferi infection develop secondary erythema migrans lesions, a common manifestation of early disseminated Lyme disease, caused by hematogenous spread of the organisms to multiple skin sites (Fig. 214-3). The secondary lesions, which can develop several days or weeks after the first lesion, are usually smaller than the primary lesion and are often accompanied by more severe constitutional symptoms. The most common early neurologic manifestations are peripheral facial nerve palsy and meningitis. Lyme meningitis usually has an indolent onset with days to weeks of symptoms that can include headache, neck pain and stiffness, and fatigue. Fever is variably present.

Of the ocular conditions reported in Lyme disease, papilledema and uveitis are most common.

Treatment

Treatment recommendations are given in Table 214-2. These have been developed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and are based on the best available evidence. There have been more clinical trials involving adults than children, so some of the pediatric recommendations derive from results of studies in adults.

| DRUG | PEDIATRIC DOSING |

|---|---|

| Amoxicillin | 50 mg/kg/day in 3 divided doses (max 1,500 mg/day) |

| Doxycycline | 4 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses (max 200 mg/day) (see text regarding doxycycline use in children) |

| Cefuroxime axetil | 30 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses (max 1,000 mg/day) |

| Ceftriaxone (IV)*† | 50-75 mg/kg/day once daily (max 2,000 mg/day) |

| RECOMMENDED THERAPY BASED ON CLINICAL MANIFESTATION | |

| Erythema migrans | Oral regimen, 14-21 days |

| Meningitis | Ceftriaxone, 10-28 days |

| Cranial nerve palsy | Oral regimen, 14-21 days (see text regarding possible need for lumbar puncture) |

| Cardiac disease | Oral regimen or ceftriaxone, 14-21 days (see text for specifics) |

| Arthritis‡ | Oral regimen, 28 days |

| Late neurologic disease | Ceftriaxone, 14-28 days |

* Cefotaxime and penicillin G are alternative parenteral agents

† Doses of 100 mg/kg/day can be used for meningitis

‡ Persistent arthritis can be treated with a second oral regimen or ceftriaxone.

From Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al: The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America, Clin Infect Dis 43:1089–1134, 2006.

Avery RA, Frank G, Glutting JJ, et al. Prediction of Lyme meningitis in children from a Lyme disease endemic region: a logistic regression model using history, physical, and laboratory findings. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e1-e7.

Costello JM, Alexander ME, Greco KM, et al. Lyme carditis in children: presentation, predictive factors, and clinical course. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e835-841.

Feder HM, Johnson BJB, O’Connell S, et al. A critical appraisal of chronic Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1422-1430.

Garro AC, Rutman M, Simonsen K, et al. Prospective validation of a clinical prediction model for lyme meningitis in children. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e829-e834.

Hayes EB, Piesman J. How can we prevent Lyme disease? N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2424-2430.

Klempner MS, Hu LT, Evans J, et al. Two controlled trials of antibiotic treatment in patients with persistent symptoms and a history of Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:85-92.

Kowalski TJ, Tata S, Berth W, et al. Antibiotic treatment duration and long-term outcomes of patients with early Lyme disease from a Lyme disease–hyperendemic area. CID. 2010;50:512-520.

2010 The Medical Letter: Treatment of Lyme disease. Med Lett. 2010;52(1342):53-54.

Nigrovic LE, Thompson AD, Fine AM, et al. Clinical predictors of Lyme disease among children with a peripheral facial palsy at an emergency department in a Lyme disease–endemic area. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e1080-e1085.

Shah SS, Zaoutis TE, Turnquist J, et al. Early differentiation of Lyme from enteroviral meningitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:542-545.

Thompson A, Mannix R, Bachur R. Acute pediatric monoarticular arthritis: distinguishing Lyme arthritis from other etiologies. Pediatrics. 2009;123:959-965.

Tuerlinckx D, Bodart E, Jamart J, et al. Prediction of Lyme meningitis based on a logistic regression model using clinical and cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:394-396.

Vázquez M, Muehlenbein C, Cartter M, et al. Effectiveness of personal protective measures to prevent Lyme disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:210-216.

Wormser GP. Early Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2794-2801.

Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Disease Society of America. CID. 2006;43:1089-1134.