53 Lung Transplant Complications

• All lung transplant recipients with respiratory complaints should be assessed for the possibility of rejection and parenchymal lung infection. In most cases, assessment leads to admission to the hospital.

• Rejection and pulmonary infection are frequently indistinguishable. The clinical manifestation of pneumonia and lung allograft rejection may be subtle, and admission is required to address both entities.

• Lung rejection is common and can occur anytime after transplantation.

• Transplanted lungs are highly susceptible to pneumonia. Cytomegalovirus pneumonia is the most common opportunistic pulmonary infection after lung transplantation.

Scope

More than 1500 lung transplants are performed each year in the United States; worldwide, approximately 3000 were performed in 2009.1 Survival rates had been rising in recent years because of technologic advances in surgical technique and immunobiology, but they seem to have reached a plateau. The current survival rate 1 year after transplantation is 79%.1 Multiple conditions necessitate lung transplantation, including cystic fibrosis, end-stage chronic obstructive lung disease, and interstitial lung disease (Box 53.1).2 The primary reason for bilateral lung transplantation is chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.3

Box 53.1

Reasons for Lung Transplantation

Emphysema/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Primary pulmonary hypertension

From United Network for Organ Sharing, 2007. Available at www.unos.org.

The number of patients who have undergone solid organ transplantation increases every year. In 2008 alone, 27,281 organ transplantations were performed in the United States.2 This figure represents a large number of patients who might seek medical care in an ED. In addition, current survival rates are rising. In 1998, 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates were 70.7%, 54.8%, and 42.6%, respectively, for lung transplant recipients. In 2009, the rates were 79%, 63%, and 52%.1 Although survival rates for lung transplantation lag behind those for other solid organ transplantations, enhancements in immunotherapy will probably continue to advance.4,5

Complications Related to the Surgical Procedure

The type of transplant (single lung, double lung, combined heart and lung, lobar) depends on the recipient’s disease and the particular transplant center where the procedure is performed.6 Single-lung transplantation requires a lateral thoracotomy incision, and double-lung transplantation requires a double thoracotomy (“clamshell”) incision. The heart may be transplanted along with one or both lungs. In some cases, a lobar segment of donor lung is transplanted. The surgical procedure includes anastomosis of the pulmonary arteries, veins, and bronchus.

Emergency Department Presentation

Patients who have undergone lung transplantation should be considered high risk when seen in an ED for evaluation. Because many patients live far from the facility where their surgery was performed, they are likely to go the nearest ED when problems arise. In a retrospective review of 131 lung and heart-lung transplant patients who visited an ED, the most common complaints were fever (37%), shortness of breath (13%), gastrointestinal symptoms (10%), and chest pain (9%).6,7

Differential Diagnosis

Patients who have undergone lung transplantation may come to the ED with myriad complaints. Among the most important complications are acute or chronic allograft rejection and infections. To make matters more complex, the required use of immunomodulating agents may diminish or mask objective findings. In addition to rejection and infection, patients in the early postoperative period are at risk for mechanical complications such as bronchial dehiscence. It is important to ascertain the procedure that was performed and the technique that was used. Patients who have received single-lung transplants are at risk for infection, cancer, and other complications in both the transplanted and the native lung.8

Rejection

Lung allograft rejection is one of the most feared life-threatening complications of lung transplantation; in some cases, the emergence of rejection necessitates retransplantation. The majority of transplant recipients experience at least one episode of rejection. Patients who experience repeated episodes of allograft rejection are at increased risk for chronic rejection (bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome).9–11

The clinical findings in patients with lung allograft rejection can be nonspecific or even silent12 (Box 53.2). Patients may report a dry cough, subjective fevers, varying degrees of shortness of breath, or any combination of these symptoms. Episodes of rejection cannot be distinguished from pulmonary infection on clinical grounds alone.9 The important point for EPs to remember is that the symptoms of allograft dysfunction or rejection may be subtle. Patients may not appear ill or seem to have anything more than a viral upper respiratory tract infection.13,14

During the first 6 months after transplantation, chest radiographs may show pleural effusions, interstitial edema, or perihilar infiltrates. Episodes of rejection occurring after this time tend to not lead to abnormalities on the chest radiograph. Normal chest film findings do not rule out the presence of underlying rejection. In the ED, chest radiographs may help in the evaluation of entities that would require immediate therapy, such as pneumothorax or a large pleural effusion.13,14

Lung allograft rejection is not usually diagnosed in the ED. Typically, patients are admitted and must undergo fiberoptic bronchoscopy and biopsy for diagnosis. Treatment of suspected lung transplant rejection begins with clinical suspicion. In all cases of suspected rejection, the patient’s pulmonologist or lung transplant surgeon should be contacted. This potentially life-threatening entity should be treated before the results of bronchoscopy become available. The biopsy indicates the presence and degree of tissue rejection and inflammation. The complex and histologically directed scale of rejection is beyond the scope of this chapter. The main ED treatment for patients with rejection is high-dose intravenous corticosteroids. Patients are usually given intravenous methylprednisolone at a dose of 0.5 to 1.0 g/day for 3 days, with the first dose given in the ED. If rejection is present, the symptoms should resolve rapidly. The therapy is then switched to oral corticosteroids. It is essential that rejection be diagnosed and treated in the ED in consultation with the patient’s transplant physician.9 Other interventions for acute rejection include methotrexate, muromonab-CD3, antithymocyte globulin, total lymphoid irradiation, and extracorporeal photopheresis.15–18

Infectious Complications

Despite or possibly as a result of advances in immunosuppression, infection is a common complication after any solid organ transplantation, particularly of the lung.19–21 Because of the lung parenchyma’s interaction with the environment, the most common infection is pneumonia, but any opportunistic infection can occur.

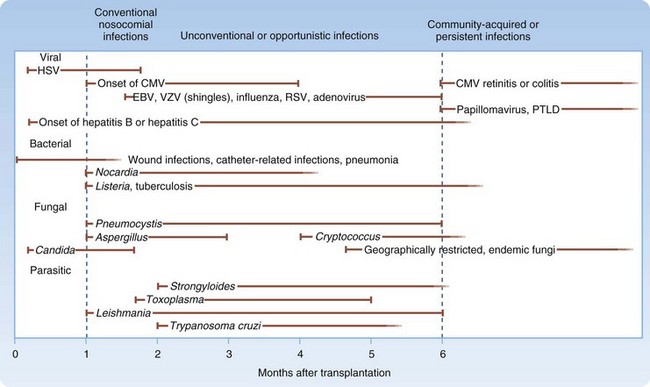

Infectious complications after organ transplantation have been studied extensively and are related to multiple factors, the most important being the time since transplantation. Infections in organ recipients can be broken down into three periods (Fig. 53.1).

During the first month after transplantation, nosocomial infections predominate. Wound infections, urinary tract infections, pneumonia, and vascular access infections are common in this period. Opportunistic infections, such as those caused by Pneumocystis and Nocardia species, do not usually occur in the first month after transplantation.22 Infections that emerge 1 to 6 months after solid organ transplantation include many of the opportunistic infections, such as those caused by Pneumocystis carinii and Listeria monocytogenes. In addition, immunomodulating viruses (particularly cytomegalovirus [CMV]) become important pathogens. Epstein-Barr virus, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and human immunodeficiency virus can also produce infection during this time frame.22

Viral infections that emerge after the first month following transplantation may be associated with chronic or progressive infection and may cause significant injury to the affected transplanted organ. Patients who experience chronic or recurrent bouts of organ rejection are invariably exposed to higher and prolonged periods of immunosuppressive therapy and thus tend to be vulnerable to these opportunistic pathogens.1

Pulmonary Infections

The lungs are particularly vulnerable to infection after solid organ transplantation. The highest risk for posttransplantation pulmonary infection occurs in lung transplant recipients. Pulmonary infections are the most common infectious complication in heart and lung transplant recipients19–21 and the least common in kidney transplant recipients.23 Multiple factors explain this higher incidence of lung infections (Box 53.3).

Box 53.3

Factors Contributing to Risk for Pulmonary Infections in Lung Transplant Recipients

Impairment in cough because of lung denervation

Narrowing of the bronchial anastomosis

Disruption of pulmonary lymphatics

From Kotloff R, Ahya V, Crawford S. Pulmonary complications of solid organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;170:22-48.

Organisms that commonly cause pulmonary infection in the postoperative period are gram-negative organisms (nosocomial) and Staphylococcus aureus. Community-acquired bacterial pneumonia tends to occur later in the posttransplantation period.16 Causative organisms include Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Legionella species. Most cases of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome are caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Patients with this syndrome commonly have recurrent episodes of purulent bronchitis and pneumonia.21 Other infections to consider are fungal pneumonia and tuberculosis (Table 53.1).

Table 53.1 Differential Diagnosis of Fever and Pulmonary Infiltrates in Organ Transplant Recipients According to the Abnormality on Chest Radiographs and Rate of Progression of the Illness

| RADIOGRAPHIC ABNORMALITY | CAUSE | |

|---|---|---|

| ACUTE ILLNESS* | SUBACUTE OR CHRONIC ILLNESS* | |

| Consolidation | ||

* Acute illness develops and requires medical attention in less than 24 hours. Subacute or chronic illness develops over a period of several days to a week.

† A nodular infiltrate is one or more focal defects greater than 1 cm2 in area on chest radiographs with well-defined borders and surrounded by aerated lung. Multiple tiny nodules are seen in a wide variety of disorders (e.g., cytomegalovirus, varicella-zoster virus infection) and are not included here.

Adapted from Shreeniwas R, Schulman LL, Berkmen YM, et al. Opportunistic bronchopulmonary infections after lung transplantation: clinical and radiographic findings. Radiology 1996;200:349-356.

Pulmonary infections in transplant patients may not cause the symptoms seen in other outpatients who have not received a transplant. As stated earlier, the symptoms may be subtle and may be as simple as a dry cough and mild upper respiratory tract discomfort. Fever in a patient receiving immunosuppressive treatment is a worrisome sign and may be the only manifestation of a serious underlying lung infection such as pneumonia. Many lung transplant recipients do not look that ill initially or do not have fulminant symptoms of pneumonia when first evaluated (Fig. 53.2).

Cytomegalovirus Infection

CMV causes one of the most important and lethal infections in solid organ recipients.23 This virus, referred to as the “troll of transplantation,” is the second most common infection in lung transplant recipients after bacterial pneumonia.24 The overall likelihood of CMV infection in a lung transplant recipient is approximately 50% and is related to the CMV status of the donor and recipient.25

CMV infection generally occurs 1 to 3 months after transplantation. Any episode of acute rejection raises the patient’s risk for continued CMV infection because of the immunosuppression required. The clinical findings may range from asymptomatic viremia to overwhelming sepsis and multiorgan failure. True clinical disease may be manifested as a mononucleosis-like syndrome with fever, malaise, and leukopenia (Box 53.4). There may also be organ-specific involvement in the lungs (pneumonitis), gastrointestinal system (colitis and hepatitis), and central nervous system. Over time, CMV infection leads to a high level of immunosuppression and the subsequent development of chronic allograft dysfunction and possibly failure.23,26,27

Pneumonitis is the most common manifestation of CMV disease after lung transplantation.28 Clinically, CMV pneumonitis may look like acute rejection. Patients with either acute lung allograft rejection or CMV pneumonitis may have low-grade fever, a nonproductive cough, and shortness of breath. Further inpatient work-up (i.e., bronchoscopy) is generally required to distinguish the cause. CMV pneumonitis is diagnosed through serologic testing and the results of bronchoscopy, discussion of which is beyond the scope of this chapter. As many as 10% to 15% of patients with CMV pneumonitis are asymptomatic initially. A prodrome consisting of fever, malaise, and myalgias frequently precedes the onset of pneumonitis (cough and dyspnea). The disease may appear as opacities, nodules, or lobar infiltrates on chest radiographs.29,30

Treatment of CMV infection may start in the ED. The diagnosis of CMV infection may not be established on initial evaluation, but a presumptive diagnosis is frequently made and empiric therapy started. Standard treatment of CMV infection consists of a 2- to 3-week course of intravenous ganciclovir.31 In some cases, ganciclovir is combined with CMV hyperimmune globulin. These therapies are usually started after the patient has been admitted.31

Medical Complications

Patients who have undergone single-lung transplantation are at increased risk for bronchogenic carcinoma in their native lung.32 Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a potential complication of any surgery, and lung transplantation increases the risk 8% to 29% over other forms of organ transplantation.33 Thus, the diagnosis of VTE and pulmonary embolism should be entertained when the initial complaint is shortness of breath or chest pain.

Patients who undergo long-term immunosuppression are at risk for posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD). Its prevalence is higher in lung transplant recipients than in other solid organ transplants.34 PTLD is typically manifested as non-Hodgkin lymphoma, which results from infection with Epstein-Barr virus, and nodules or masses can be seen on the chest film.35

Diagnostic Testing

Diagnostic imaging in the ED is usually limited to plain film chest radiography and, occasionally, computed tomography (CT). EPs should maintain a low threshold for obtaining a CT scan of the chest in lung transplant recipients. CT has been shown to be far superior to chest radiography in detecting subtle cases of pneumonia in transplant patients.36

Immunosuppressive Therapy

Medications commonly used in lung transplant patients are calcineurin inhibitors (e.g., cyclosporine), cell cycle inhibitors, and corticosteroids. Their side effects are listed in Table 53.2. Most patients are maintained on a combination of these classes of medications.

Table 53.2 Drugs Commonly Used in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients

| DRUG | MECHANISM OF ACTION | ADVERSE EFFECTS |

|---|---|---|

| Corticosteroids (prednisone) | Inhibits expression of genes encoding proinflammatory cytokines | Cushingoid features, infection, hypertension, edema, osteoporosis, bone necrosis, psychiatric disease |

| Azathioprine | Inhibitor of purine synthesis | Leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia, hepatotoxicity, increased risk for malignancy |

| Mycophenolate (CellCept) | Inhibits purine synthesis | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dyspepsia, leukopenia, anemia |

| Cyclosporine (Sandimmune, Neoral); causes renal vasoconstriction and ischemia | Calcineurin inhibitor (impairs T-cell function) | Nephrotoxicity (acute or chronic renal failure, renal vasoconstriction), infections, hypertension, hyperkalemia, increased lipids and glucose, gout, hypomagnesemia, tremor, encephalopathy, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), hirsutism, gingival hyperplasia, hepatotoxicity |

| Tacrolimus (FK-506, Prograf) | Calcineurin inhibitor | Same as cyclosporine except much less risk for TTP |

| Sirolimus | Inhibits cell proliferation (T cells) | Infections, thrombocytopenia, anemia, leukopenia, hyperlipidemia, edema, diarrhea, headaches |

| Cyclophosphamide | Interferes with B-cell and T-cell proliferation and function | Leukopenia, hemorrhagic cystitis, bladder cancer, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion |

| OKT3-monoclonal (used to treat rejection) | Targets CD3+ T cells and impairs their function Transiently activates T cells |

“Cytokine release syndrome” (fever, tachycardia, hypotension), pulmonary edema, aseptic meningitis |

| ATGAM-polyclonal | Bind to peripheral lymphocytes | Anaphylaxis, serum sickness, fever, rash |

| Interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor antibodies (daclizumab, basiliximab) | Bind to IL-2 receptor | Rare hypersensitivity syndrome |

Many commonly used medications may interfere with drugs used for long-term immunosuppression. Medications known to increase the blood levels (and thus toxicity) of certain medications include cyclosporine (Neoral) and tacrolimus (Prograf). In particular, erythromycin, doxycycline, and azole antifungal agents (ketoconazole, fluconazole, itraconazole) all raise serum concentrations of cyclosporine and tacrolimus. In contrast, other medications, such as isoniazid, rifampin, and rifabutin, lower the blood levels of these two immunosuppressants and may put the patient at risk for organ rejection. Sulfonamides, ganciclovir, and acyclovir potentiate the bone marrow toxicity of azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil.37–40

Treatment and Disposition

All patients with suspected lung transplant rejection or infection should be admitted to the hospital for further diagnostic testing and evaluation. The importance of appreciating the subtle nature of these complications cannot be overemphasized. It is wise to seek consultation with the patient’s pulmonary physician or surgeon. A safe way to evaluate any lung transplant recipient seen in the ED is to assume that infection or rejection is present until proved otherwise (Box 53.5).

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

Do not assume that patients with allograft rejection or pneumonia will manifest obvious symptoms.

Admit patients to the hospital if rejection or infection is suspected.

Discuss every lung transplant recipient seen in the emergency department with the patient’s pulmonary physician or lung transplant surgeon.

Institute therapy with broad-spectrum antibiotics if pulmonary symptoms are present or pneumonia is suspected.

Treat suspected rejection with high-dose intravenous corticosteroids in conjunction with consultation.

Chakinala MM, Trulock EP. Acute allograft rejection after lung transplantation: diagnosis and therapy. Chest Surg Clin North Am. 2003;13:525–542.

Christie JD, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, et al. The registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: twenty-seventh official adult lung and heart-lung transplant report—2010. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29:1104–1118.

Hachem RR. Lung allograft rejection: diagnosis and management. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2009;14:477–482.

Zaas DW. Update on medical complications involving the lungs. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2009;14:488–493.

1 Christie JD, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, et al. The registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: twenty-seventh official adult lung and heart-lung transplant report—2010. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29:1104–1118.

2 OPTN Data. 2009 Annual Report of the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients: transplant data 1999–2008. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Healthcare Systems Bureau, Division of Transplantation; 2009.

3 Knoop C, Estenne M. Disease-specific approach to lung transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2009;14:466–470.

4 Hosenpud JD, Bennett LE, Keck BM, et al. The registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: fifteenth official report—1998. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1998;17:656–668.

5 Lin HM, Kauffman HM, McBride MA, et al. Center-specific graft and patient survival rates: 1997 United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) report. JAMA. 1998;280:1153–1160.

6 Boujoukos AJ. Management of patients with heart and lung transplants, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2005.

7 Sternbach GL, Varon J, Hunt SA. Emergency department presentation and care of heart and heart/lung transplant recipients. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:1140–1144.

8 Zaas DW. Update on medical complications involving the lungs. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2009;14:488–493.

9 De Vito Dabbs A, Hoffman LA, Iacono AT, et al. Are symptom reports useful for differentiating between acute rejection and pulmonary infection after lung transplantation? Heart Lung. 2004;33:372–380.

10 Palmer SM, Burch LH, Davis RD, et al. The role of innate immunity in acute allograft rejection after lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:628–632.

11 Chakinala MM, Trulock EP. Acute allograft rejection after lung transplantation: diagnosis and therapy. Chest Surg Clin North Am. 2003;13:525–542.

12 Hachem RR. Lung allograft rejection: diagnosis and management. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2009;14:477–482.

13 Millet B, Higenbottam TW, Flower CD, et al. The radiographic appearances of infection and acute rejection of the lung after heart-lung transplantation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:62–67.

14 Otulana BA, Higenbottam T, Scott J, et al. Lung function associated with histologically diagnosed acute lung rejection and pulmonary infection in heart-lung transplant patients. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:329–332.

15 Valentine VG, Robbins RC, Wehner JH, et al. Total lymphoid irradiation for refractory acute rejection in heart-lung and lung allografts. Chest. 1996;109:1184–1189.

16 Benden C, Speich R, Hofbauer GF, et al. Extracorporeal photopheresis after lung transplantation: a 10-year single-center experience. Transplantation. 2008;86:1625–1627.

17 Cahill BC, O’Rourke MK, Strasburg KA, et al. Methotrexate for lung transplant recipients with steroid-resistant acute rejection. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1996;15:1130–1137.

18 Shennib H, Massard G, Reynaud M, et al. Efficacy of OKT3 therapy for acute rejection in isolated lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1994;13:514–519.

19 Maurer JR, Tullis DE, Grossman RF, et al. Infectious complications following isolated lung transplantation. Chest. 1992;101:1056–1059.

20 Cisneros JM, Munoz P, Torre-Cisneros J, et al. Pneumonia after heart transplantation: a multi-institutional study. Spanish Transplantation Infection Study Group. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:324–331.

21 Kramer MR, Marshall SE, Starnes VA, et al. Infectious complications in heart-lung transplantation. Analysis of 200 episodes. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:2010–2016.

22 Fishman JA, Rubin RH. Infection in organ-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1741–1751.

23 Kotloff RM, Ahya VN, Crawford SW. Pulmonary complications of solid organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:22–48.

24 Zamora MR. Cytomegalovirus and lung transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:1219–1226.

25 Zamora MR. Controversies in lung transplantation: management of cytomegalovirus infections. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2002;21:841–849.

26 Duncan SR, Paradis IL, Yousem SA, et al. Sequelae of cytomegalovirus pulmonary infections in lung allograft recipients. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146:1419–1425.

27 Sia IG, Patel R. New strategies for prevention and therapy of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in solid-organ transplant recipients. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:83–121.

28 Shreeniwas R, Schulman LL, Berkmen YM, et al. Opportunistic bronchopulmonary infections after lung transplantation: clinical and radiographic findings. Radiology. 1996;200:349–356.

29 Franquet T, Lee KS, Muller NL. Thin-section CT findings in 32 immunocompromised patients with cytomegalovirus pneumonia who do not have AIDS. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:1059–1063.

30 Collins J, Muller NL, Kazerooni EA, et al. CT findings of pneumonia after lung transplantation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175:811–818.

31 Harbison MA, De Girolami PC, Jenkins RL, et al. Ganciclovir therapy of severe cytomegalovirus infections in solid-organ transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1988;46:82–88.

32 Dickson RP, Davis RD, Rea JB, et al. High frequency of bronchogenic carcinoma after single-lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25:1297–1301.

33 Kahan ES, Petersen G, Gaughan JP, et al. High incidence of venous thromboembolic events in lung transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2007;26:339–344.

34 Reams BD, McAdams HP, Howell DN, et al. Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder: incidence, presentation, and response to treatment in lung transplant recipients. Chest. 2003;124:1242–1249.

35 Halkos ME, Miller JI, Mann KP, et al. Thoracic presentations of posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders. Chest. 2004;126:2013–2020.

36 Macori F, Iacari V, Falchetto Osti M, et al. Assessment of complications in patients with lung transplantation with high resolution computerized tomography. Radiol Med. 1998;96:42–47.

37 Mignat C. Clinically significant drug interactions with new immunosuppressive agents. Drug Saf. 1997;16:267–278.

38 Michalets EL. Update: clinically significant cytochrome P-450 drug interactions. Pharmacotherapy. 1998;18:84–112.

39 Knoop C, Haverich A, Fischer S. Immunosuppressive therapy after human lung transplantation. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:159–171.

40 Lake KD, Canafax DM. Important interactions of drugs with immunosuppressive agents used in transplant recipients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;36(Suppl B):11–22.