50 Lung Infections

• A wide variety of infectious agents, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi, cause pneumonia.

• Diagnosis and treatment of pneumonia are determined by assessment of patient risk factors, other elements of the history, diagnostic studies, and physical examination.

• Special care must be taken to identify patients at risk for health care–associated pneumonia or unusual or resistant organisms.

• Chest radiography is an important diagnostic tool that can offer valuable clues to the etiology. Other laboratory and sputum studies may also be useful.

• Because the causative agent is typically not known at initial evaluation, timely institution of carefully selected empiric antibiotic therapy is paramount.

• Age, comorbid diseases, and clinical and laboratory data guide disposition decisions for a patient with pneumonia, such as admission to an intensive care unit.

• Isolation measures such as droplet precautions should be initiated immediately for patients with acute febrile respiratory illnesses.

Epidemiology

Pneumonia is one of the most common infectious diseases encountered in the emergency department (ED), with more than 1.5 million visits for this infection annually.1 When combined with influenza, pneumonia ranks as the sixth leading cause of death in the United States and the most common cause of infection-related mortality.2–5

Pathophysiology

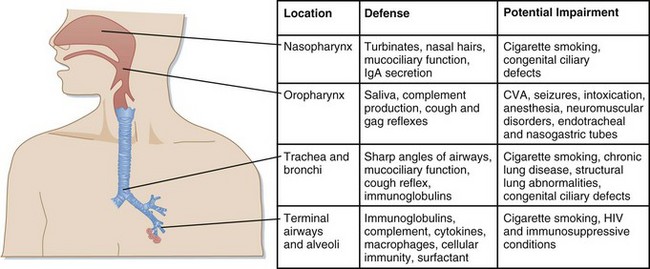

Pneumonia typically occurs when the protective defenses just described are breached and the lungs are exposed to a heavy inoculation of organisms or to very virulent organisms. The lung’s defenses can be impaired at multiple levels. Aspiration can result when altered levels of consciousness secondary to a neurologic insult or alcohol or drug intoxication impair the gag reflex. The upper airway defenses are often bypassed by endotracheal tubes or tracheostomy. Smoking and chronic lung disease can impair mucociliary function. Bronchial obstruction secondary to tumor or lymphadenopathy can lead to obstruction and pneumonia. Immunologic impairment as a result of infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), chemotherapy, splenectomy, or advanced age also predisposes to pneumonia. The elderly are particularly vulnerable because of impairments at many of these levels and a higher incidence of comorbid conditions5 (Fig. 50.1).

Fig. 50.1 Host defenses against infection.

CVA, Cerebrovascular accident; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IgA, immunoglobulin A.

(Modified from Donowitz G, Mandell G. Acute pneumonia. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Doline R, editors. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious disease. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2005. pp. 819-41.)

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

A goal-directed, comprehensive history is very important in the evaluation of a patient with pneumonia. Historical clues such as risk for aspiration, recent travel, animal or environmental exposure, HIV status or risk, alcoholism, and comorbid illnesses can point toward specific causes and guide the proper choice of initial empiric therapy (Table 50.1).6,7 Special care should be taken to identify patients at risk for health care–associated pneumonia (HCAP), such as recent health care and antibiotic exposure, which could predispose them to multidrug-resistant pathogens and alter treatment choices.8

Table 50.1 Epidemiologic Conditions Related to Specific Pathogens in Patients with Selected Community-Acquired Pneumonia

| CONDITION | COMMONLY ENCOUNTERED PATHOGENS |

|---|---|

| Alcoholism | Streptococcus pneumoniae, oral anaerobes |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and/or smoking | S. pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, Legionella spp., Chlamydia pneumoniae |

| Poor dental hygiene | Oral anaerobes |

| Aspiration/lung abscess | Oral anaerobes |

| Exposure to bats or to soil enriched with bird droppings | Histoplasma capsulatum |

| Exposure to birds | Chlamydia psittaci, avian influenza (poultry exposure) |

| Exposure to rabbits | Francisella tularensis |

| Exposure to farm animals or parturient cats | Coxiella burnetii (Q fever) |

| Human immunodeficiency virus infection: | |

| Early | S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

| Late | Above plus Pneumocystis jiroveci (carinii), Cryptococcus, Histoplasma |

| Travel to or residence in the southwestern United States | Coccidioides spp. |

| Travel to or residence in Asia | Burkholderia pseudomallei, severe acute respiratory syndrome |

| Influenza active in the community (“flu season”) | Influenza, S. pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, H. influenzae |

| Structural lung disease (e.g., bronchiectasis) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Burkholderia cepacia, S. aureus |

| Injection drug use | S. aureus, skin anaerobes, M. tuberculosis, S. pneumoniae |

| Endobronchial obstruction | Anaerobes, S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, S. aureus |

| Recent hospitalization or nursing home residence | Drug-resistant S. pneumoniae, gram-negative bacilli, S. aureus |

| In the context of bioterrorism | Bacillus anthracis (anthrax), Yersinia pestis (plague), F. tularensis (tularemia) |

Modified from File T, Niederman M. Antimicrobial therapy of community-acquired pneumonia. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2004;18:993-1016.

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Look for key clues in the history and physical findings that would suggest pneumonia caused by an unusual or resistant organism.

Identify patients at risk for health care–associated pneumonia.

Maintain high suspicion for aspiration pneumonia in the elderly and in patients with altered mental status or a recent cerebrovascular accident.

Pathogens

Community-acquired pneumonia is often defined as pneumonia in a patient who has not been hospitalized and has not resided in a long-term care facility for more than 14 days before the appearance of symptoms.3 With the growing prevalence of mixed-organism infections, drug-resistant pathogens, and patients with comorbid illnesses, this definition has become somewhat more complicated. Guidelines from the American Thoracic Society (ATS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) now address the treatment of patients at increased risk for pseudomonal infection, those with significant comorbid conditions, and those at risk for infection with drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae.

The most common etiologic agent causing pneumonia is S. pneumoniae, which is responsible for about two thirds of all cases (Table 50.2).3 Other bacterial pathogens that are often isolated are Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Legionella pneumophila (often called “the atypical organisms”). Community-acquired pneumonia is also caused by several viruses, including influenza, parainfluenza, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Other pathogens, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, drug-resistant S. pneumonia, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), should additionally be considered in patients who have had recent health care exposure or have recently taken broad-spectrum antibiotics. Multiple other organisms may be considered based on a history of specific exposures, travel, and lung or immunosuppressive diseases.

| PATHOGEN | PREVALANCE (%) |

|---|---|

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 20-60 |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 3-10 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 3-5 |

| Gram-negative bacilli | 3-10 |

| Miscellaneous (includes Moraxella catarrhalis, group A streptococci, and Neisseria meningitidis, each accounting for 1-2% of cases) | 3-5 |

| Legionella spp. | 2-8 |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | 1-6 |

| Chlamydia pneumoniae | 4-6 |

| Viruses | 2-15 |

| Aspiration | 6-10 |

From Niederman M. Review of treatment guidelines for community acquired pneumonia. Am J Med 2004;117;52S.

Special Populations

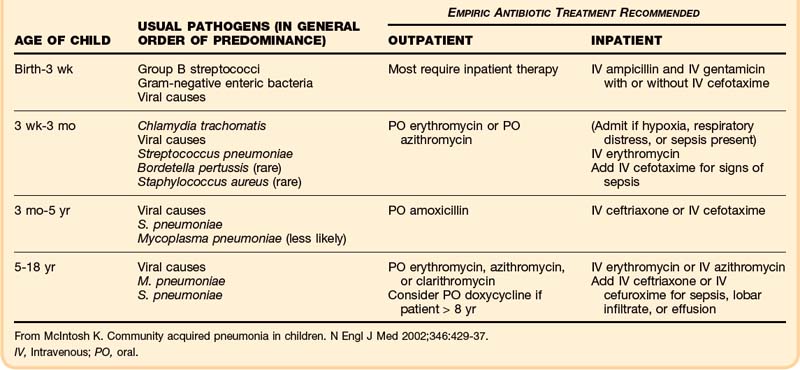

Children

Pneumonia and acute bronchiolitis are the most common lower respiratory tract infections in children. They are caused by a variety of viruses and bacteria, with the prevalence varying by age group9,10 (Table 50.3). As in adults, S. pneumoniae is the predominant organism causing pneumonia except in newborns, in whom group B streptococci and gram-negative bacilli dominate. H. influenzae type b remains an important bacterial pathogen causing pneumonia in the developing world. It has nearly been eliminated in the United States through immunization practices. Pneumococcal vaccines also appear to be lowering the incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease and pneumonia, but more data are needed.11 Many viruses, mainly influenza, parainfluenza, and RSV, can also cause pneumonia in children. Most children with pneumonia have cough, fever, and abnormal lung findings. Signs of tachypnea and increased work of breathing are often present and may be the only signs of disease in infants.9

Pertussis (whooping cough) is a respiratory tract infection worthy of special mention. Caused by the organism Bordetella pertussis, it typically affects young children and adolescents. The incidence of the disease has markedly decreased because of immunization. Pertussis is manifested in three distinct stages. The first (catarrhal) stage consists of a mild cough, conjunctivitis, and coryza lasting up to 2 weeks. The second stage consists of severe paroxysms of coughing, often followed by strong inhalations of air, which produces the characteristic “whoop.” This stage can last up to 4 weeks. The third (convalescent) stage consists of a chronic cough. The disease is important to identify because multiple complications can occur, such as complete airway obstruction, secondary pneumonia, seizures, and encephalitis. Treatment is with oral erythromycin or azithromycin. Close contacts of the patient should receive prophylactic antibiotics.9

Patients Infected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Pneumonia is one of the most common serious bacterial illnesses affecting patients infected with HIV. In addition to the common community-acquired pathogens, patients with HIV are more susceptible to opportunistic infections with Pneumocystis carinii, pulmonary tuberculosis, and recurrent bacterial pneumonia. Antibiotic chemoprophylaxis, highly active antiretroviral therapy, and preventive vaccines appear to be significantly improving the incidence and the morbidity and mortality of pneumonia in patients with HIV.12

Aspiration Pneumonia

Aspiration of oral or gastric contents can occur in the setting of altered mental status or dysfunctional swallowing reflexes secondary to neurologic impairment such as stroke. Aspiration is typically “silent,” and therefore a high index of clinical suspicion is needed for making the proper diagnosis. Aspiration can lead to chemical pneumonitis and bacterial aspiration pneumonia more than 60% of the time.5 Abscesses and empyema can occur in more advanced cases. The pathogens involved are typically those found in the oropharynx. Patients who have recently been hospitalized or who reside in nursing homes may be colonized with S. aureus or gram-negative bacilli, which can cause aspiration pneumonia. Treatment with clindamycin or piperacillin-tazobactam is generally indicated.

Influenza

Influenza is one of the most common and most serious viral infections causing pneumonia. Influenza usually has a seasonal occurrence, typically from December to April. Bacterial superinfections can occur with pneumonia caused by influenza, most commonly with S. pneumoniae or S. aureus. Rapid identification tests are available to assist in diagnosis. Antiviral therapy with amantadine or rimantadine (for influenza A) or oseltamivir (for influenza A and B) may lessen the symptoms and quicken recovery if started within 48 hours of the onset of illness. In spring 2009 a novel influenza A virus (H1N1) spread globally and resulted in the first influenza pandemic since 1968, with infection occurring outside the usual influenza season in many parts of the world.13 The pandemic put nearly all health care and public health institutions to the test and offered valuable lessons in emergency preparedness, virus detection, antiviral treatment, and immunization.

Community-Acquired Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus

MRSA is usually considered a nosocomial pathogen and accounts for 20% to 40% of all cases of HCAP and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP).14 A new variant with a different genetic makeup, community-acquired MRSA, has been observed to cause cases of severe and rapidly progressing community-acquired pneumonia. It is typically seen in young and previously healthy patients, often with preceding influenza-like illnesses. Chest radiographs generally reveal multilobar cavitating infiltrates. Currently, intravenous vancomycin or linezolid is recommended, but the optimal treatment regimen has yet to be determined and may eventually include a combination of antibiotics with antibacterial and antitoxin mechanisms of action.1

Evaluation and Diagnostic Testing

Chest Radiographs

Most authorities agree that chest radiographs (posteroanterior and lateral if possible) should be obtained in all patients with suspected pneumonia. Radiographs help confirm the diagnosis of pneumonia and provide possible clues to the causative agent (Table 50.4). Radiographs will also demonstrate associated conditions, such as lung abscess, bronchial obstruction, and pleural effusion (Figs. 50.2 to 50.4). Computed tomography may be necessary for further evaluation of complex infiltrates with pleural effusions, suspected masses, or abscesses. Typical radiologic patterns are expected with certain infections (see Table 50.4). It is important to remember that multiple factors, such as age, immune status, hydration status, and underlying lung disease, can alter the radiographic appearance of pneumonia.15

Table 50.4 Etiologic Agents of Pneumonia and Common Radiographic Patterns

| RADIOGRAPHIC PATTERN | PATHOPHYSIOLOGY | TYPICAL PATHOGENS |

|---|---|---|

| Lobar or multilobar infiltrate with air bronchograms | Edema fluid/inflammatory reaction in alveoli occurring initially in the periphery of the lung Larger bronchi usually remain patent and cause air bronchograms |

Bacterial pneumonias (Streptococcus pneumoniae, Klebsiella, Legionella) |

| Interstitial infiltrates | Edema and inflammatory cellular infiltrate in interstitial tissue surrounding small airways and vessels | Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Pneumocystis jiroveci (carinii), viral pneumonias |

| Bronchopneumonia | Diffuse patchy infiltrates and peribronchial thickening secondary to large and intermediate airway involvement | Staphylococcus aureus, gram-negative organisms, fungi |

| Abscesses | Abscess cavity, isolated or within areas of consolidation | S. aureus, Pseudomonas, anaerobes |

| Cavitary masses | Inflammation and necrosis of lung parenchyma | Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Nocardia, Aspergillus, Actinomyces |

From Tarver R, Teague S, Heitkamp D, et al. Radiology of community acquired pneumonia. Radiol Clin North Am 2005;43:497-512.

Sputum Studies

Sputum Gram stain and culture should be performed only if a good-quality specimen can be obtained, transported, and processed appropriately. Sputum studies should be strongly considered for severe pneumonia, for suspected MRSA, in patients with radiographs consistent with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and in patients who are critically ill.16,17 Sputum cultures should routinely be ordered in cases of suspected hospital-acquired pneumonia, HCAP, and VAP.18 In the ED setting, sputum studies may be particularly useful in rapid testing for influenza or RSV in peak seasons to help select appropriate antiviral therapy and avoid unnecessary antibiotic use.

Blood Cultures

In a 2005 study of 414 ED patients with pneumonia, Kennedy et al. found that blood culture results rarely altered antibiotic therapy decisions. Resistant organisms requiring a broadening of antibiotic therapy were identified in only 1% of patients.19 In a 2009 American College of Emergency Physicians clinical policy statement, the committee concluded that routine use of blood cultures has low yield and rarely leads to a change in management or outcome. A more patient-tailored approach has been suggested, with blood cultures being reserved for higher-risk groups such as those admitted to intensive care units (ICUs) with severe pneumonia, immunocompromised status, or significant comorbid conditions.20

Other Studies

A complete blood count and basic serum chemistry studies are typically performed in patients admitted with pneumonia. The blood count can identify disorders such as lymphopenia (possibly indicating HIV infection), neutropenia, and anemia and thus help guide appropriate therapy. Electrolyte and glucose abnormalities are often found in patients with pneumonia, and testing for them may provide prognostic information. Measurement of blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine is important in determining the level of nursing care and appropriate antibiotic dosing for each patient. Urinary studies such as antigen testing for Legionella and S. pneumoniae may be useful. Bronchoscopy may be considered in patients with HIV, patients who are immunosuppressed, and patients in whom an unusual infection is suspected. Two newer serum biomarkers, C-reactive protein and procalcitonin, may be useful in predicting patients at risk for increased 30-day mortality. In addition, serial measurements of procalcitonin may be useful for guiding the duration of antibiotic therapy.1,21 Thoracentesis may be necessary if a pleural effusion is present and freely flowing. Ultrasonography may be beneficial in identifying free-flowing effusions and to guide sampling of the fluid for cell count, cultures, pH, and fluid analysis.17

Treatment

As already described, the ATS and IDSA have issued detailed guidelines for the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia. Several studies have demonstrated lower mortality in hospitalized patients treated with guideline-recommended antimicrobial regimens.6 In a 2004 study of 420 patients with pneumonia, Mortensen et al.22 found significantly lower 30-day mortality in patients who received antimicrobial therapy in concordance with the ATS or IDSA guidelines.

The recommendations in the guidelines are summarized in Box 50.1. The guidelines group recommendations according to the site of therapy (outpatient, inpatient, or ICU), severity of disease, comorbid illnesses, and risk for resistant organisms or Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Box 50.1

Recommended Empiric Antibiotics for Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Outpatient Treatment

1. Previously healthy and no use of antimicrobials within the previous 3 months:

2. Presence of comorbid conditions such as chronic heart, lung, liver, or renal disease; diabetes mellitus; alcoholism; malignancies; asplenia; immunosuppressing conditions or use of immunosuppressing drugs; or use of antimicrobials within the previous 3 months (in which case an alternative from a different class should be selected):

3. In regions with a high rate (>25%) of infection with high-level (MIC = 16 mcg/mL) macrolide-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae, consider use of the alternative agents listed above in No. 2 for patients without comorbid conditions (moderate recommendation; level III evidence)

Special Concerns

If Pseudomonas is a consideration:

If community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is a consideration, add vancomycin or linezolid (moderate recommendation; level III evidence)

ICU, Intensive care unit; MIC, minimal inhibitory concentration.

From Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44:S27-S72.

Ideally, antibiotic therapy should be started in the ED as soon as possible after the diagnosis is made. Because pneumonia accounts for approximately 1.7 million hospitalizations per year with an estimated annual cost of more than $9 billion, improving pneumonia care has become a focus of the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.20 Several defined quality measures (core measures) have been indentified, including the use of evidence-based antibiotic choices, timely antibiotic administration, appropriate use of blood cultures before administration of antibiotics, and administration of pneumococcal and influenza vaccines for appropriate patients. Although the validity of some of the measures are questioned by some authorities, these data are publicly reported and adherence with the measures is often a priority for institutions.

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

Provide immediate supplemental oxygen or ventilatory assistance (or both) to patients with suspected pneumonia as needed.

A mask should be placed over the face of any patient with suspected pneumonia to prevent spread of disease to other patients waiting for evaluation.

Antibiotic therapy should ideally be initiated in the emergency department as soon as possible after the diagnosis is made.

Health Care–Associated Pneumonia

In the current era of shorter hospital stays and expanded home and long-term care facility treatment, the emergency physician frequently encounters patients at risk for HCAP. In 2005, a joint committee of the ATS and IDSA published an additional set of guidelines for the evaluation and treatment of HCAP. They also apply to hospital-acquired pneumonia and VAP. The guidelines emphasize that HCAP can be caused by a wide variety of bacteria, including multidrug-resistant pathogens, gram-negative organisms, and MRSA, and is often polymicrobial. It is recommended that sputum cultures be performed in all such patients, before antibiotic therapy if possible. The recommendations for initial empiric antibiotic therapy are summarized in Table 50.5. The commission also recognized the variability in bacterial pathogens from one institution to another and recommended that local microbiologic data be taken into account when selecting antibiotic therapy.18

Table 50.5 Initial Empiric Antibiotic Therapy Recommendations for Health Care–Associated Pneumonia

| SITUATION | POTENTIAL PATHOGENS | RECOMMENDED ANTIBIOTIC |

|---|---|---|

| No known risk factors for multidrug-resistant pathogens,* early onset (<5 days’ hospitalization) |

* Risks include antimicrobial therapy in the preceding 90 days, current hospitalization of 5 days or longer, high frequency of antibiotic resistance in the institution or community, hospitalization for 2 days or more in the preceding 90 days, residence in a nursing home or extended care facility, home infusion therapy, long-term dialysis within 30 days, home wound care, family member with multidrug-resistant pathogens, and immunosuppressive diseases or therapy.

† If MRSA is a risk factor or has a high incidence locally.

From American Thoracic Society. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171;388-416.

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

In 1997 the Pneumonia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT)23 published a prediction rule to identify patients at low risk for death from pneumonia within 30 days; it is now known as the PORT criteria or the Pneumonia Severity Index. A 2005 comparison of three prediction guidelines by Aujesky et al.24 found the Pneumonia Severity Index to be most accurate in identifying low-risk and high-risk patients with pneumonia. The system was developed through analysis of data from thousands of patients with community-acquired pneumonia and was validated in more than 50,000 patients. Patients are divided into five classes based on increasing risk for mortality. Class I (mortality, 0.1% to 0.4%) is assigned on the basis of an age of 50 years or younger and key information from the history and physical examination. Other classes are identified with a point system calculated from the presence of historical data and physical and laboratory findings (Box 50.2).23

Box 50.2

Summary of Risk Class Assignment for Patients with Pneumonia Based on the Pneumonia Severity Index (PORT Criteria)

Step 2

| CHARACTERISTIC | POINTS ASSIGNED |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Men | Age in years (1 point for each year) |

| Women | Age in years (1 point for each year) − 10 |

| Nursing home residency | +10 |

| Coexisting Illnesses | |

| Neoplastic disease | +30 |

| Liver disease | +20 |

| Congestive heart failure | +10 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | +10 |

| Renal disease | +10 |

| Physical Findings | |

| Altered mental status | +20 |

| Respiratory rate > 30 breaths/min | +20 |

| Systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg | +20 |

| Temperature < 35° C or > 40° C | +15 |

| Pulse > 125 beats/min | +10 |

| Laboratory and Radiographic Findings | |

| Arterial pH < 7.35 | +30 |

| Blood urea nitrogen > 30 mg/dL | +20 |

| Sodium < 130 mmol/L | +20 |

| Blood glucose > 250 mg/dL | +10 |

| Hematocrit < 30% | +10 |

| PaO2 < 60 mm Hg or pulse oximetry value < 90% | +10 |

| Pleural effusion | +10 |

Data from Fine M, Auble T, Yealy D, et al. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med 1997;336:243-50; and Aujesky D, Auble T, Yealy D, et al. Prospective comparison of three validated prediction rules for prognosis in community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med 2005;118:384-92.

Class I and class II patients are considered to have very low risk (30-day mortality, <1%) and can probably be treated as outpatients. Many patients in class III (30-day mortality, <2.8%) might also be candidates for outpatient treatment. Patients in class IV or class V are at much higher risk (30-day mortality, 8.5% to 31.1%) and should probably be admitted to the hospital.23,24

The British Thoracic Society has also published a prediction tool, CURB-65, to identify patients at high risk for 30-day mortality. Confusion, elevated blood urea nitrogen, elevated respiratory rate, low systolic or diastolic blood pressure, and age older than 65 years are the high-risk variables identified. A simplified version (CRB-65) allows prediction based on clinical variables alone (eliminating blood urea nitrogen) and may be useful in the outpatient setting. A score of 2 or higher predicts increased risk for mortality, and these patients should probably be admitted. ICU admission should be considered for those with a score of 3 or higher.1

American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Subcommittee (Writing Committee) on Critical Issues in the Evaluation and Management of Adult Patients Presenting to the Emergency Department With Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:704–731.

Niederman M. Recent advances in community-acquired pneumonia: inpatient and outpatient. Chest. 2007;131:1205–1215.

Slaven E, Santanilla J, DeBlieux P. Healthcare-associated pneumonia in the emergency department. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;30:46–51.

1 Niederman M. Recent advances in community-acquired pneumonia: inpatient and outpatient. Chest. 2007;131:1205–1215.

2 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Pneumonia and influenza death rates—United States, 1979-1994. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;44(28):535–537.

3 Bartlett J, Dowell S, Mandell L, et al. Practice guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:347–382.

4 File T, Niederman M. Antimicrobial therapy of community-acquired pneumonia. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2004;18:993–1016.

5 Donowitz G, Mandell G. Acute pneumonia. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Doline R. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious disease. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2005:819–841.

6 Niederman M. Review of treatment guidelines for community acquired pneumonia. Am J Med. 2004;117:51S–57S.

7 Fine M, Smith M, Carson C, et al. Prognosis and outcomes of patients with community acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 1996;275:134–141.

8 Slaven E, Santanilla J, DeBlieux P. Healthcare-associated pneumonia in the emergency department. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;30:46–51.

9 Fleisher FR. Infectious disease emergencies. In: Fleisher GR, Ludwig S, Henretig FM, et al. Textbook of pediatric emergency medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:783–851.

10 McIntosh K. Community acquired pneumonia in children. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:429–437.

11 Lucero M, Dulalia VE, Parreno RN. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines for preventing vaccine-type invasive pneumococcal disease and pneumonia with consolidation on x-ray in children under two years of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1, 2004. CD004977

12 Feldman C. Pneumonia associated with HIV infection. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2005;18:165–170.

13 Writing Committee of the WHO Consultation on Clinical Aspects of Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Influenza. Clinical aspects of pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1708–1719.

14 Rubinstein E, Kollef M, Nathwani D. Pneumonia caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:5378–5385.

15 Tarver R, Teague S, Heitkamp D, et al. Radiology of community acquired pneumonia. Radiol Clin North Am. 2005;43:497–512.

16 Mandell LA, Wunderink PG, Anzueto A, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:S27–S72.

17 Mandell L, Bartlett J, Dowell S, et al. Update of practice guidelines for the management of community-acquired pneumonia in immunocompetent adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:1405–1433.

18 American Thoracic Society. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:388–416.

19 Kennedy M, Bates D, Wright S, et al. Do emergency department blood cultures change practice in patients with pneumonia? Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46:393–400.

20 American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Subcommittee (Writing Committee) on Critical Issues in the Evaluation and Management of Adult Patients Presenting to the Emergency Department With Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:704–731.

21 Torres A, Rello J. Update in community-acquired and nosocomial pneumonia 2009. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:782–787.

22 Mortensen E, Restrepo M, Anzueto A, et al. Effects of guideline-concordant antimicrobial therapy on mortality among patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med. 2004;117:726–731.

23 Fine M, Auble T, Yealy D, et al. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:243–250.

24 Aujesky D, Auble T, Yealy D, et al. Prospective comparison of three validated prediction rules for prognosis in community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med. 2005;118:384–392.