1 Lung Anatomy

Development and Gross Anatomy

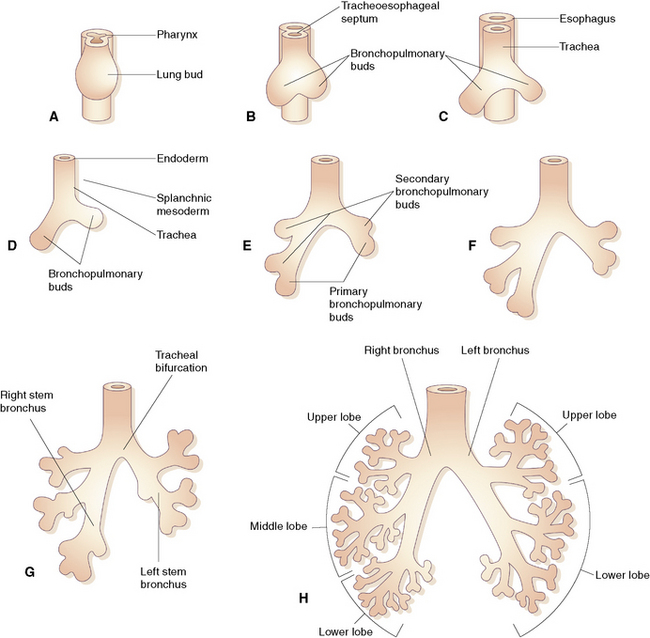

Airway Development

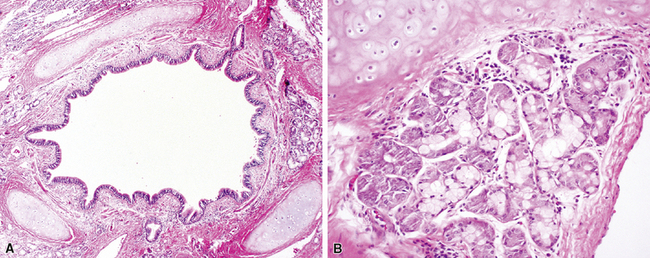

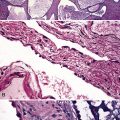

During early embryogenesis (at approximately day 21 after fertilization), the lungs begin as a groove in the ventral floor of the foregut (Fig. 1-1) This foregut depression becomes a diverticulum of endoderm, surrounded by an amorphous condensation of splanchnic mesoderm that lengthens caudally in the midline, anterior to the esophagus. By the fourth week of gestation, two lung buds form as distal outpouchings.1,2 A series of repetitive nondichotomous branchings begins during week 5 and results in the formation of the primordial bronchial tree by the eighth week of gestation.

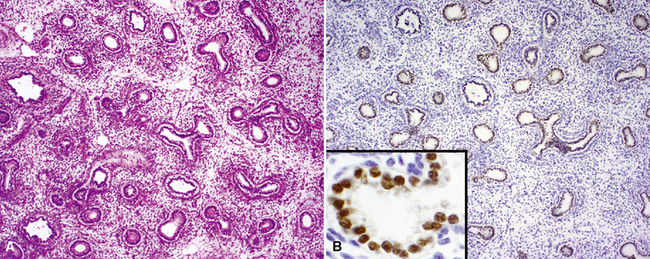

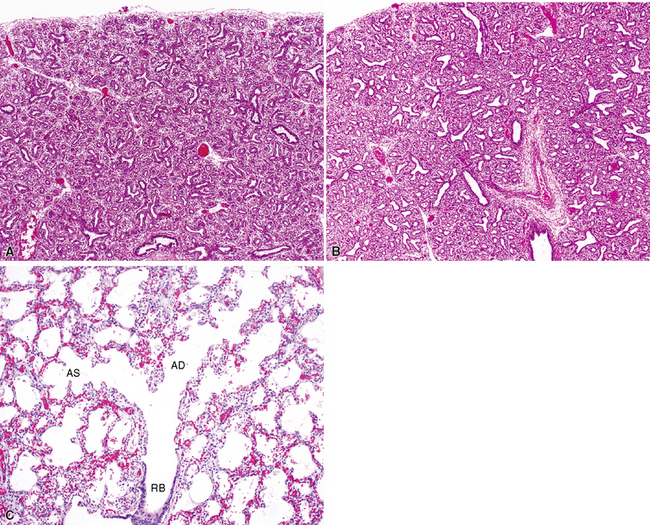

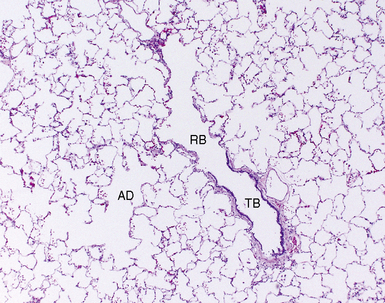

By 17 weeks, the rudimentary structure of the conducting airways has formed. This phase of lung development is referred to as the “pseudoglandular stage” because the fetal (postgestational week 7) lung is composed entirely of tubular elements that appear as circular gland-like structures in two-dimensional tissue sections (Fig. 1-2). The subsequent stages of development (canalicular, 13–25 weeks; terminal sac, 24 weeks to birth; and alveolar, late fetal to the age of 8–10 years) are dedicated to the formation of the essential units of respiration, the acini1–5 (Fig. 1-3). The postnatal lung continues to accrue alveoli until the age of approximately 10 years (Fig. 1-4).

The Pleura

Immediately after their formation, the lung buds grow into the medial walls of the pericardioperitoneal canals (splanchnic mesoderm) and in doing so become invested with a membrane that will be the visceral pleura (analogous to a fist being pushed into a balloon.) In this process, the lateral wall of the pericardioperitoneal canal becomes the parietal pleura, and the compressed space between becomes the pleural space (Fig. 1-5).

The Lung Lobes

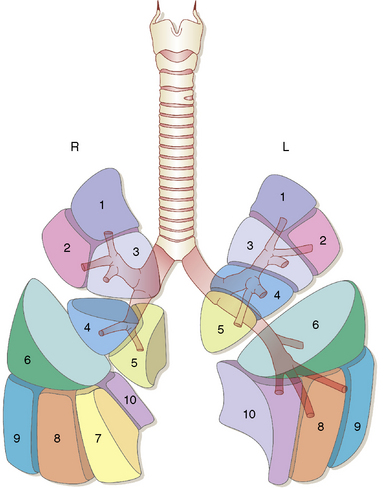

By the end of gestation, five well-defined lung lobes are present, three on the right (upper, middle, and lower lobes) and two on the left (upper and lower lobes).3,6,7 Each of the five primary lobar buds is invested with visceral pleura. Each lobe in turn is composed of one or more segments, resulting in a total of 10 segments per lung (Fig. 1-6). The presence of the heart leads to the formation of a rudimentary third lobe on the left side termed the lingula (more properly regarded as a part of the left upper lobe than as an independent structure). In fact, the right middle lobe and the lingula are analogous structures: Each has an excessively long and narrow bronchus, predisposing these lobes to the pathologic effects of bronchial compression by adjacent lymph nodes or other masses. When such compression occurs, the consequent chronic inflammatory changes in the respective lobe are referred to as “middle lobe syndrome.”8

Figure 1-6 Ten distinct segments are present in each lung.

(Reprinted with permission from Nagaishi C. Functional Anatomy and Histology of the Lung. Baltimore: University Park Press; 1972.)

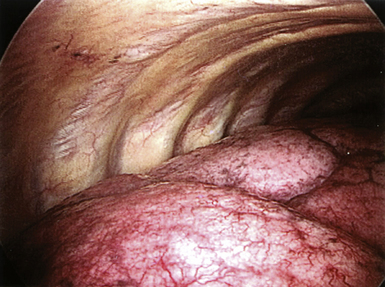

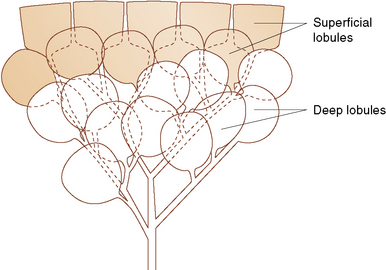

As gestation proceeds, airway branching continues to the level of the alveolar sacs, with a total of about 23 final subdivisions (20 of which occur proximal to the respiratory bronchioles). In successive order proceeding distally, the anatomic units formed are the lung segments, secondary and primary lobules (Fig. 1-7), and finally acini. With each successive division, the resulting airway branches are smaller than their predecessors, but each has a diameter greater than 50% of the airway parent. This phenomenon leads to a progressive increase in airway volume with each successive branching and a significant reduction in airway resistance in more distal lung. The acinus consists of a central respiratory bronchiole that leads to an alveolar duct and terminates in an alveolar sac, composed of many alveoli (Fig. 1-8).

Microscopic Anatomy

The microscopic lung structure relevant to this chapter begins with the trachea and conducting airways and ends with the alveolar gas exchange units. This overview is intended to refresh the surgical pathologist’s existing knowledge of the normal lung. For the reader interested in greater detail, the comprehensive and authoritative review of gross and microscopic lung anatomy by Nagaishi is recommended.4

The Conducting Airways

The Trachea

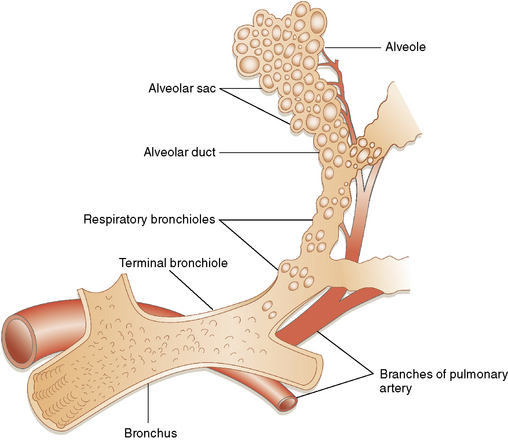

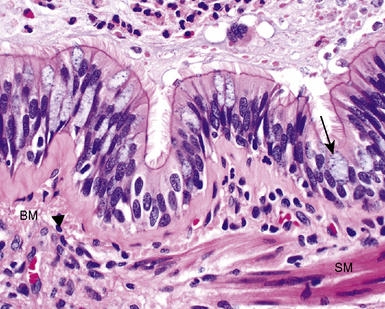

The trachea is the gateway to the lung and is exposed to environmental factors in highest concentration. This rigid tube is designed for conducting gas, with rigid C-shaped cartilage rings that protect it from frontal injury and also prevent collapse during the negative changes in intrathoracic pressure that occur during respiration. The open side of the cartilage ring faces posteriorly, where the trachealis muscle completes the tracheal circumference. This arrangement allows the esophagus to abut the “soft” side of the trachea, down to the level of the carina. Respiratory epithelium (pseudostratified, ciliated, columnar-type), submucous glands, and smooth muscle combine to prepare inspired air for use in the lung by adding moisture and warmth (Fig. 1-9) while trapping dust particles and chemical vapor droplets before they can reach more delicate peripheral lung. For all of these reasons, when diseases affect the trachea, the potential for impact on general respiratory function is significant.

The Bronchi

The bronchi begin at the carina and extend into the substance of the lung. They are large conducting airways that have cartilage in their walls. As in the trachea, the cartilage of the primary bronchi is C-shaped, but this configuration changes to that of puzzle piece–like plates once the bronchus enters the lung parenchyma. Within the substance of the lung, the cartilage plates decrease in density progressively as the bronchial diameter decreases, resulting in increasing area between individual plates. Mucous glands are positioned just beneath the surface epithelium and may be seen in endobronchial biopsy specimens (Fig. 1-10). When inflamed or distorted by crush artifact, they may simulate granulomas or tumor. These glands connect to the airway lumen by a short duct. The bronchi divide and subdivide successively, becoming ever smaller on their way to the peripheral lung.

The Bronchioles

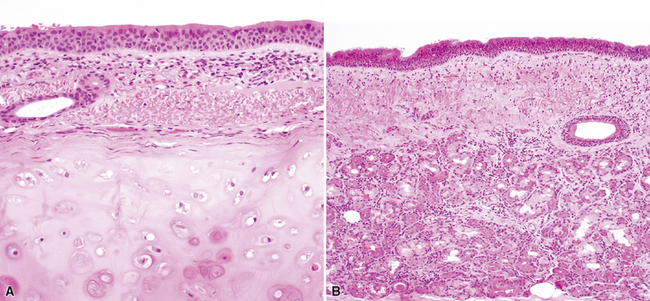

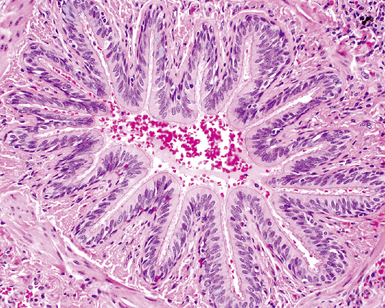

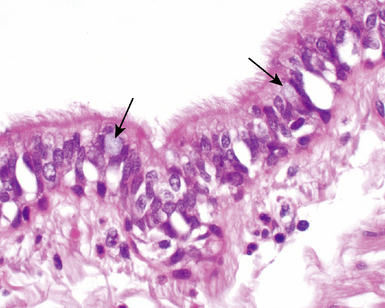

The bronchioles are the final air conductors and by definition lack cartilage altogether (and therefore sometimes are referred to as “membranous”) (Fig. 1-11). The bronchioles have no alveoli; these are acquired more distally in the pulmonary acinus. The terminal bronchiole is the smallest conducting airway without alveoli in its walls. There are about 30,000 terminal bronchioles in the lungs, and each of these, in turn, directs air to approximately 10,000 alveoli. The cells that line the airways are columnar in shape and ciliated. Their nuclei are present at multiple levels in each cell—a phenomenon referred to as pseudostratification (Fig. 1-12).

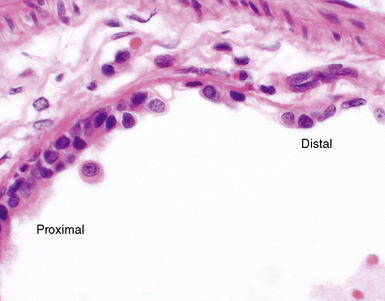

Pseudostratified columnar epithelium typically is identifiable as far distal as the smallest terminal bronchioles, where the cells then rapidly become more cuboidal in shape and their nuclei more basally situated (Fig. 1-13). In the normal mucosa, mucus-secreting cells (goblet cells) typically are present in low numbers, most often as individual units. It may be quite difficult to identify any goblet cells in the epithelium of small bronchioles. When these cells are numerous, they may be distended with mucus; this finding should suggest the presence of underlying airway disease (Fig. 1-14).

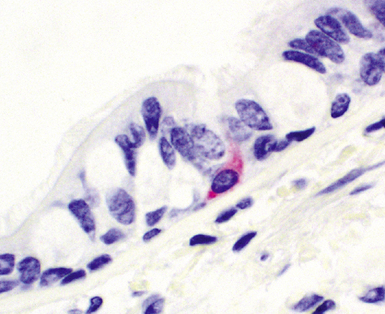

Airway Mucosal Neuroendocrine Cells

Airway mucosal neuroendocrine cells typically present as single cells in the respiratory epithelium with clear cytoplasm (Fig. 1-15). Rarely, these cells may aggregate to form so-called neuroepithelial bodies. Immunohistochemical stains decorate these cells when addressed with antibodies directed against the common neuroendocrine markers chromogranin A and synaptophysin, as well as a number of more esoteric neuropeptides. The exact function of these cells is unknown. It has been suggested that lung neuroendocrine cells play a role in regulating ventilation-perfusion relationships and also may be important in airway morphogenesis.9

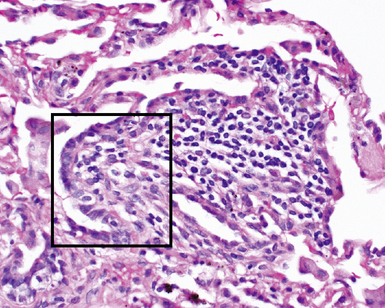

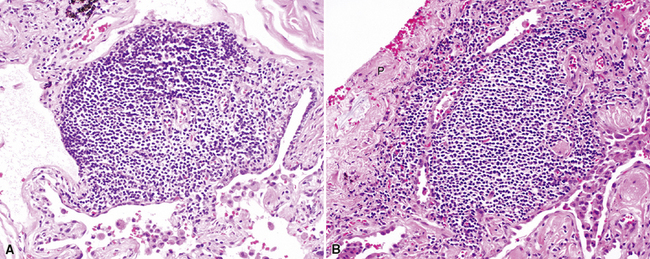

Airway-Associated Lymphoid Tissue

Airway-associated lymphoid tissue may be present in the normal lung, but in such instances it is very sparse and typically occurs at the bifurcation points of the airways (Fig. 1-16). This lung lymphoid tissue generally is referred to as bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT) and is believed to be analogous to the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) of the gastrointestinal tract.10 The strategic localization of BALT at airway divisions may be a consequence of exposure to inhaled antigens and other airstream particles that are likely to strike these areas.11 BALT foci are associated with specialized epithelial cells in the mucosa, and the constituent lymphoid cells (mainly T lymphocytes) are admixed with macrophages and dendritic cells. The epithelial and dendritic cells of the BALT presumably play a role in the detection of inhaled allergens, viruses, and bacteria; accordingly, BALT is considered to be a critical component of the lung’s immune defense system. The bronchial BALT may become hyperplastic, with follicular germinal center formation. Such germinal centers may be sampled at bronchoscopic biopsy, presenting a potential diagnostic challenge when crushed or cut in such a way that the follicular center lymphoid cells appear as a nodule or sheet in the specimen. BALT also may be important in diseases of immunologic origin that produce bronchiolitis, such as connective tissue diseases (e.g., Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis), as well as graft-versus-host disease in organ transplantation, immunoglobulin deficiency states, and even inflammatory bowel disease.

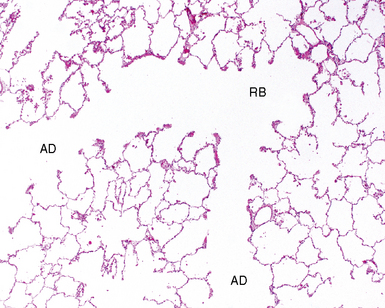

The Acinus

The acinus begins distal to the terminal bronchiole and is where most of the gas exchange occurs in the lungs. The acinus includes (in order proceeding distally) the respiratory bronchioles (primary and secondary), the alveolar ducts, and the alveolar sacs (Fig. 1-17). Respiratory bronchioles have progressively more alveoli in their walls with successive distal generations. The last conducting structure, the alveolar duct, is entirely lined by alveoli. The alveolar ducts terminate in alveolar sacs, which are globular aggregations of adjacent alveoli. As the airways of the acinus branch and diminish in diameter progressively, an abrupt transition from cuboidal cells to flattened epithelium is seen.

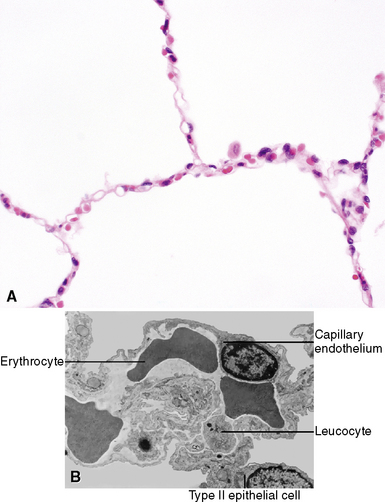

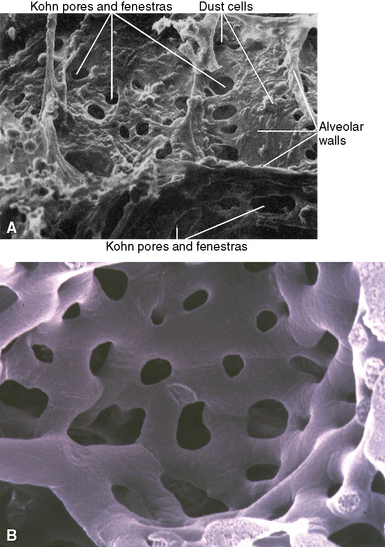

The Alveoli

Most of the alveolar surface that faces the inspired air is covered by extremely flat type I epithelial cells that are not readily seen with the light microscope. These thin and flattened cells are well suited to gas exchange (Fig. 1-18). The type II epithelial cells are cuboidal in shape, and although they cover less surface area, they are greater in total number than the type I cells. They are present at the angular junctions of alveolar walls (the alveolus being more like a geodesic dome than a sphere). The surface of the type II cell facing the alveolar airspace has microvilli that can sometimes be appreciated on light microscopy as slight roughening. Type II cells contain large numbers of organelles and are responsible for the production of surfactant, a substance that lowers surface tension and is essential for preventing alveolar collapse at low intra-alveolar pressures. Type II cells are the progenitor cells of the alveolar type I cells and, after an injury, divide and replace them. Type I and type II cells have tight junctions that present a physical barrier between the interstitial fluid and the alveolar air.

The Alveolar Walls

The alveolar walls are composed of a capillary net (Fig. 1-19), the extracellular matrix, and sparse cellular elements including mast cells, smooth muscle cells, pericytes, fibroblast-like cells, and occasional lymphocytes.12 The mesenchymal cells of the interstitium have been the subject of considerable study. Unstimulated, they resemble fibroblasts and have few organelles. During the repair phase of an injury, actin and myosin appear in the cytoplasm and develop contractile properties that play an important role in lung repair.13–15 Capillary endothelial cells within the acinus are joined by tight or semi-tight junctions. The semi-tight junctions exist to allow larger molecules to traverse the capillary wall.

The Pulmonary Arteries

The pulmonary arteries carry venous blood to the lungs for gas exchange with the inspired air in the alveolar spaces. The pulmonary circulation is a low-pressure system (with a mean systolic pressure of 14 mm Hg) and is considerably shorter in length than the systemic circulation.16,17 Nevertheless, a doubling of the resting blood flow to the lung results in only a small increase (by approximately 5 mm Hg) in pressure.

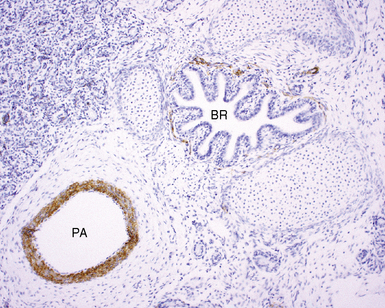

The pulmonary arteries arise from the conus arteriosus of the right ventricle of the heart and run in parallel with the airways within the lung.18,19 The main trunk of the pulmonary artery bifurcates into right and left main trunks at the fourth thoracic vertebral body. These trunks follow the right and left main bronchi into the lung (Fig. 1-20). The diameter of the pulmonary artery and that of the accompanying airway in cross section are roughly equal. The pulmonary arteries branch at a rate similar to that for the airways but also have a second distinctive branching pattern identifiable in peripheral lung, with right-angle origins for branches having significantly smaller caliber (Fig. 1-21) designed to supply peribronchiolar alveoli.

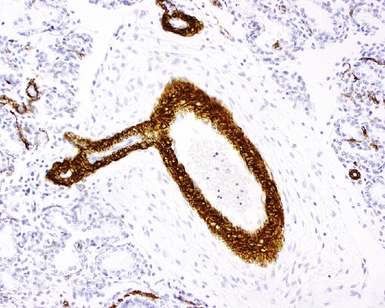

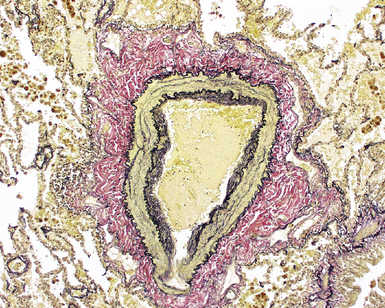

The pulmonary arteries are composed of three layers, the intima, the media, and the adventitia, similar to the systemic arteries; however, for arteries of the same diameter, systemic vessels have a significantly thicker muscular layer. In the adult, two or more elastic laminae are present in arteries larger than 1 mm in diameter. Arteries between 100 and 200 μm (between 0.1 and 0.2 mm) in diameter are muscular and have internal and external elastic laminae (Fig. 1-22). Smaller arteries may be muscular or nonmuscular. The two elastic laminae appear fused in smaller arteries as a result of progressive attenuation of smooth muscle. Where muscle is absent, a single fragmented elastic lamina is all that separates the intima from the adventitia. In the adult, arterial muscle extends down to the level of the alveoli. The ratio of arterial wall thickness to external arterial diameter often is a useful marker for abnormality. Nondistended muscular arteries have a medial thickness that should represent approximately 5% of external arterial diameter.

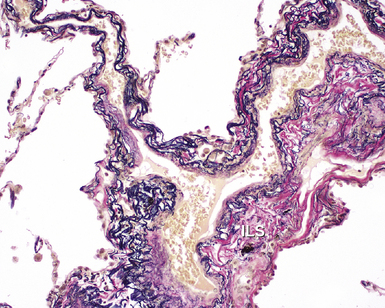

The Pulmonary Veins

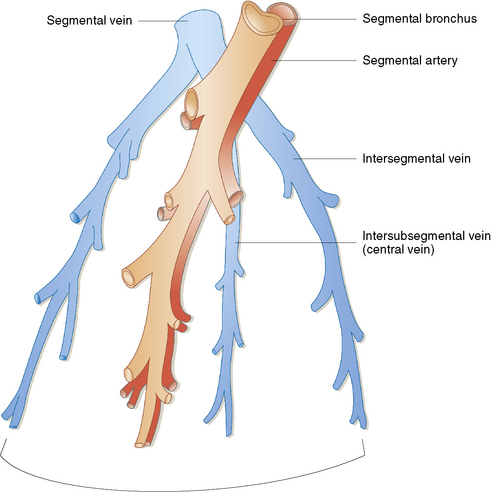

The pulmonary veins carry oxygenated blood back to the heart for systemic distribution. The large veins are present adjacent to the main arteries at the hilum, but the pulmonary veins within the lung parenchyma travel along a separate course within the interlobular septa, beginning on the venous side of the alveolar capillary bed. The intralobular pulmonary veins coalesce to form larger channels that join the interlobular septa at the periphery of the acinus (Fig. 1-23). The veins are indistinct structures in the lung and often are difficult to identify.18,20 Most of the vascular structures identifiable at scanning magnification in tissue sections of lung are pulmonary arteries (with their adjacent airway). The most reliable method for locating a pulmonary vein in tissue sections is to find the junction of the pleura with an interlobular septum (Fig. 1-24). This is an important technique, because every lung biopsy for diffuse disease should be evaluated systematically in search of pathologic alterations in each of the main compartments (airways, arteries, veins, acinar structures, and pleura). The veins have a single elastic lamina (Fig. 1-25) and sparse smooth muscle.

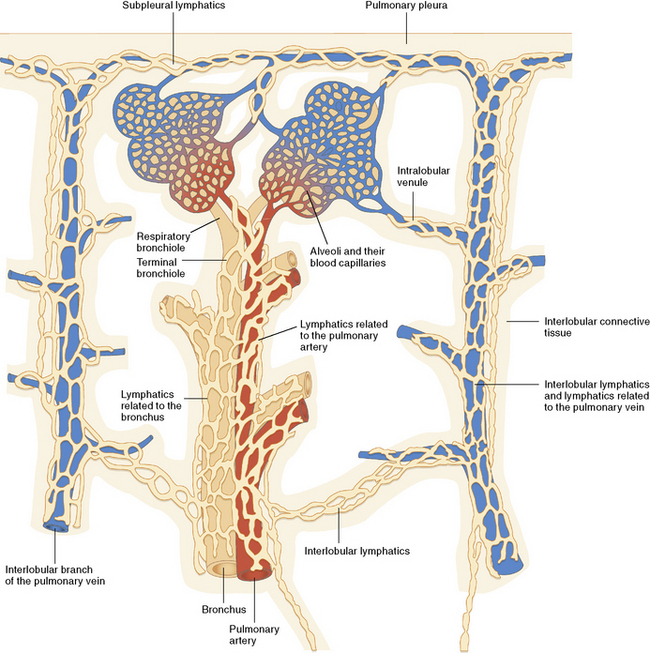

Figure 1-23 The lobular relationship of pulmonary arteries and veins is illustrated in this simplified diagram.

(Reprinted with permission from Nagaishi C. Functional Anatomy and Histology of the Lung. Baltimore: University Park Press; 1972.)

The Bronchial Arteries

The bronchial arteries supply arterial blood to the lung and arise most commonly from the descending aorta, although a number of anomalous origins are described. The bronchial arteries run parallel to the airways within the bronchovascular sheath, where small branches supply capillary networks of the mucosa, airway smooth muscle, and adventitia.20,21 The largest-diameter bronchial arteries can be seen in the adventitia of the airway. Submucosal branches are nearly imperceptible. On the venous side of the bronchial artery–supplied capillary net, bronchial veins within the lung eventually join pulmonary veins and return their blood to the left atrium.

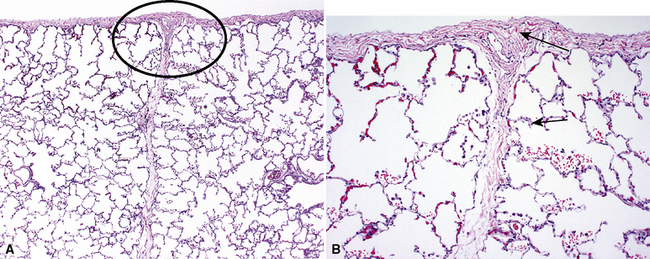

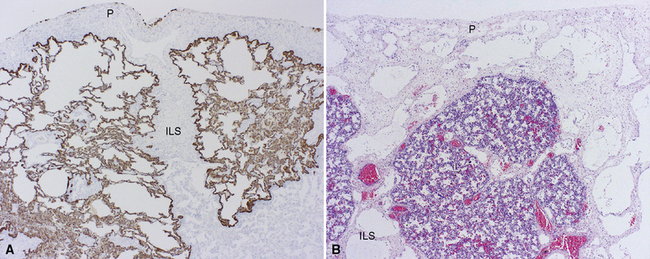

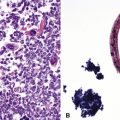

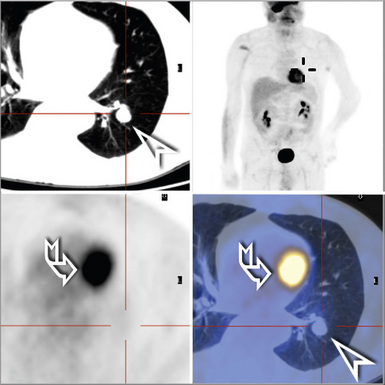

The Pulmonary Lymphatics

The lymphatic vessels of the peripheral lung begin at the outer edge of the acinus, draining along interlobular septa to coalesce finally at the hilum.22 A separate centriacinar system is present in the bronchovascular sheaths, beginning around the level of the respiratory bronchiole.23 No lymphatics are present in the alveolar sacs, where it is believed that the interstitial space serves the purpose of extracellular fluid collection and drainage to more proximal regions. The lymphatic net of the pulmonary arteries extends further distally in the acinus than does that associated with the terminal airways.23 The lymphatic networks of the airways and pulmonary arteries anastomose freely during their course back to the hilum. The lymphatics (and veins) also are distributed over the surface of the lobes within the pleura. The relationship among airways, arteries, veins, and lymphatics is nicely illustrated by Okada,23 in Figure 1-26. When affected by certain diseases such as diffuse lymphangiomatosis (Fig. 1-27A) or lymphangiectasis (see Fig. 1-27B), the distribution of the pulmonary lymphatics becomes much more apparent.

Other Pulmonary Lymphoid Tissue

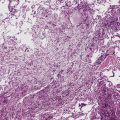

Lymphoid Aggregates

Lymphoid aggregates are uncommon in the lung under normal circumstances. They have no capsule and are composed of B cells, T cells, and dendritic cells. Lymphoid aggregates increase in the lungs of cigarette smokers11,24 and may be present within interlobular septa or the pleura (Fig. 1-28) and in the subpleural connective tissue.25 Lymphoid aggregates may be one of the sources for the condition known as diffuse lymphoid hyperplasia.

Dendritic Cells

Dendritic cells are antigen-presenting cells that function in concert with T lymphocytes to develop acquired immunity. Dendritic cells occur in the epithelium and subepithelial tissue of the airways. Their kidney-shaped nucleus is eccentrically placed, and they feature prominent cytoplasmic protrusions. Dendritic cells strongly express the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) antigens.26 A subpopulation of dendritic cells carry the Langerhans cell marker24 and contain Birbeck granules in their cytoplasm on ultrastructural examination.27 Langerhans cells are increased in the lungs of smokers and can be identified by immunohistochemical techniques using antibodies directed against S100 protein and CD1a. The Langerhans cell is involved in the smoking-related disease known as pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis (formerly known as pulmonary eosinophilic granuloma or histiocytosis X).

1 Moore K. The Developing Human. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1973.

2 Langeman J. Medical Embryology, 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1969.

3 Wells L.J., Boyden E.A. The development of the bronchopulmonary segments in human embryos of horizons XVII to XIX. Am J Anat.. 1954;95(2):163-201.

4 Nagaishi C. Functional Anatomy and Histology of the Lung. Baltimore: University Park Press, 1972.

5 Boyden E.A. Development of the pulmonary airways. Minn Med.. 1971;54(11):894-897.

6 Boyden E.A. Observations on the anatomy and development of the lungs. Lancet.. 1953;73(12):509-512.

7 Boyden E.A. Observations on the history of the bronchopulmonary segments. Minn Med.. 1955;38(9):597-598.

8 Kwon K.Y., Myers J.L., Swensen S.J., Colby T.V. Middle lobe syndrome: a clinicopathological study of 21 patients. Hum Pathol.. 1995;26(3):302-307.

9 Aguayo S., Schuyler W., Murtagh J., et al. Regulation of branching morphogenesis by bombesin-like peptides and neutral endopeptidase. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol.. 1994;10:635-642.

10 Bienenstock J., Johnston N., Perey D. Bronchial lymphoid tissue I. Morphological characteristics. Lab Invest. 1973;28:686-692.

11 Richmond I., Pritchard G., Ashcroft T., et al. Bronchus associated lymphoid tissue (BALT) in human lung: its distribution in smokers and non-smokers. Thorax.. 1993;48:1130-1134.

12 Thurlbeck W. Chronic airflow obstruction. In: Churg A., editor. Pathology of the Lung. 2nd ed. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers; 1995:739-825.

13 Fukuda Y., Ishizaki M., Masuda Y., et al. The role of intraalveolar fibrosis in the process of pulmonary structural remodeling in patients with diffuse alveolar damage. Am J Pathol.. 1987;126(1):171-182.

14 Leslie K., King T.E.Jr, Low R. Smooth muscle actin is expressed by air space fibroblast-like cells in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Chest.. 1991;99(suppl 3):47S-48S.

15 Leslie K.O., Mitchell J., Low R. Lung myofibroblasts. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton.. 1992;22(2):92-98.

16 Parker J.C., Cave C.B., Ardell J.L., et al. Vascular tree structure affects lung blood flow heterogeneity simulated in three dimensions. J Appl Physiol.. 1997;83(4):1370-1382.

17 Li C.W., Cheng H.D. A nonlinear fluid model for pulmonary blood circulation. J Biomech.. 1993;26(6):653-664.

18 Huang W., Yen R.T., McLaurine M., Bledsoe G. Morphometry of the human pulmonary vasculature. J Appl Physiol.. 1996;81(5):2123-2133.

19 Hislop A.A. Airway and blood vessel interaction during lung development. J Anat.. 2002;201(4):325-334.

20 Boyden E.A. Human growth and development. Am J Anat.. 1971;132(1):1-3.

21 Boyden E.A. The developing bronchial arteries in a fetus of the twelfth week. Am J Anat.. 1970;129(3):357-368.

22 Okada Y., Ito M., Nagaishi C. Anatomical study of the pulmonary lymphatics. Lymphology.. 1979;12(3):118-124.

23 Okada Y. Lymphatic System of the Human Lung. Siga, Japan: Kinpodo Publishing, 1989.

24 van Haarst J., de Wit H., Drexhage H., Hoogsteden H.C. Distribution and immunophenotype of mononuclear phagocytes and dendritic cells in the human lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol.. 1994;10(5):487-492.

25 Kradin R., Mark E. Benign lymphoid disorders of the lung, with a theory regarding their development. Hum Pathol.. 1983;14:857-867.

26 Van Voorhis W., Hair L., Steinman R., Kaplan G. Human dendritic cells. Enrichment and purification from peripheral blood. J Exp Med.. 1982;155(4):1172-1187.

27 Soler P., Moreau A., Basset F., Hance A.J. Cigarette smoking-induced changes in the number and differentiated state of pulmonary dendritic/Langerhans cells. Am Rev Respir Dis.. 1989;139(5):1112-1117.