Lumps in the head and neck and salivary calculi

Introduction

Thyroid swellings may be confused with other anterior neck swellings, so head and neck examination must include the thyroid area, described in Chapter 49.

Mouth problems are managed by oral and maxillofacial surgeons but patients often seek advice first from another clinician. Thus most doctors, particularly in an accident department, should understand the essentials of oral and dental disease and their management (see also Ch. 48).

History and examination in the head and neck

Many different tissues are concentrated here, so there is a profusion of conditions causing lumps. Box 47.1 provides a simple classification.

Special points in the history and examination

Most lumps are best examined with the patient sitting so the examiner can palpate from in front and behind. The examiner should establish the characteristics of the lump (Box 47.2) and determine how it relates to overlying or underlying structures. For example, a lump in the cheek may originate in skin, parotid, buccinator muscle, oral mucosa or parotid duct. In clinical exams, it is useful to describe the characteristics as if to someone who cannot see the patient.

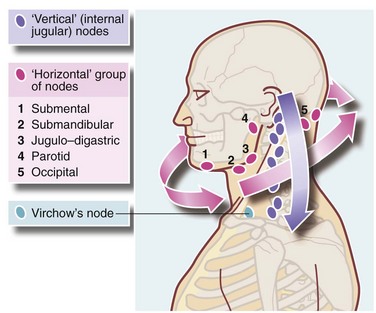

With a lump or swelling, the whole of scalp, back of neck and skin behind and in the ears should be examined. Head and neck lymph nodes must be palpated. A simple method considers nodes lying in two planes, horizontal and vertical (Figure 47.1) which can be examined systematically. For lumps in the lower half of the face or submandibular region, the oral cavity should be examined to exclude salivary gland lesions, oral malignancies or sources of infection such as a dental abscess. For lumps in the parotid region, the integrity of the facial nerve should be tested since malignant tumours often cause neurological deficits. If the presenting complaint is lymph node enlargement, endoscopy of upper airways and pharynx may be necessary to exclude primary tumours or infected lesions.

Examination of the oral cavity

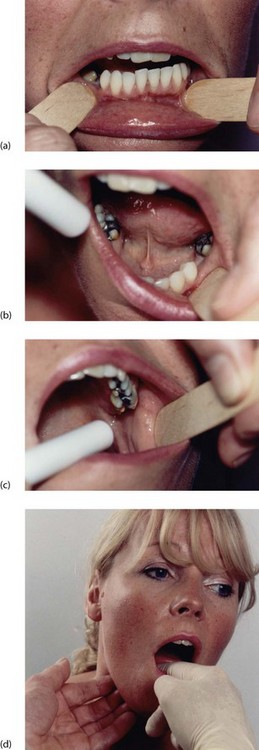

For many doctors, asking the patient to open the mouth represents the entire oral examination. The simple technique illustrated in Figure 47.2a–d, will enable most significant lesions to be seen without special instruments or lighting.

Fig. 47.2 Technique of oral examination

Teeth, gums and buccal sulci can be inspected by retracting the lips with wooden spatulas or fingers (a). The palate is inspected by tilting the patient’s head back and retracting the lips, and the floor of the mouth and movements of the tongue examined as shown in (b). The parotid papilla is demonstrated in (c). Finally, bimanual palpation of the submandibular area, including the course of the submandibular duct, is performed with a gloved finger inside the mouth, as shown in (d)

First, the patient should remove dentures. Then lips and their mucosal lining, and the lining of cheeks and gums are inspected. To do this, the lips are retracted by the examiner’s gloved fingers or a wooden spatula and the mouth illuminated with a pen torch. Teeth are inspected for obvious decay and gum inflammation. A flap of gum over a partially erupted lower wisdom tooth can cause painful inflammation (Fig. 48.6).

Lumps in the floor of the mouth, submandibular area and cheeks should be palpated bimanually as shown in Figure 47.2d. Lumps in these areas are often mobile and tend to move away from examining fingers.

Tumours of salivary glands

Salivary gland tumours

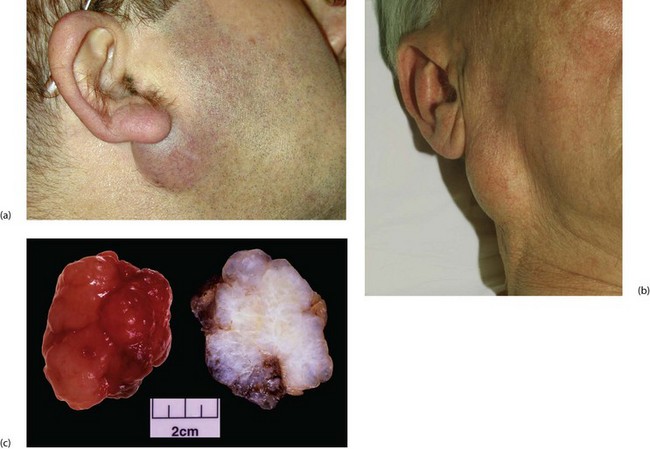

Clinically, pleomorphic adenoma presents as a very slowly growing, painless lump (see Fig. 47.3). Most are in the parotid, some in the submandibular gland and a few are in minor salivary glands.

Fig. 47.3 Pleomorphic adenomas of the parotid

(a) Small lesion in the typical position below the ear lobe, between the posterior border of the ramus of the mandible and the upper end of the sternomastoid. (b) Larger lesion in an older man. This had been present at least 4 years before the patient presented. (c) Pathological specimen of large pleomorphic adenoma removed by extracapsular dissection. On the left the specimen has been freshly removed and shows the typical knobbly surface. On the right, the fixed and cut specimen shows the variegated and predominantly myxomatous appearance

Treatment: Treatment is by excision. For superficial lesions, the standard operation has long been superficial parotidectomy to excise all glandular tissue superficial to the facial nerve, but nowadays many surgeons perform extracapsular dissection of the lump alone. In benign disease this cures the problem and carries a lower risk of side-effects, particularly facial nerve damage and Frey’s syndrome of gustatory sweating (see below). Recurrence is uncommon with either procedure. For deeper lesions, an attempt should be made to excise the entire lesion, carefully identifying and preserving the facial nerve branches. Again, extracapsular dissection may be the safer option.

Complications of parotid surgery: The main complication is facial nerve damage. Damage to the temporal or upper zygomatic branches may prevent complete closure of the eye, leading to corneal drying and damage. Mandibular branch damage causes weakness at the angle of the mouth and embarrassing salivary dribbling. Nerve damage may also complicate submandibular gland excision: the mandibular branch of the facial nerve is vulnerable if the incision is incorrectly sited, and the lingual and hypoglossal nerves lie close to the deep surface of the gland. Damage causes unilateral tongue wasting and numbness respectively.

Salivary gland stone disease (sialolithiasis)

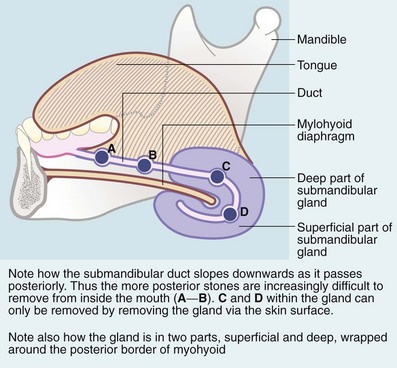

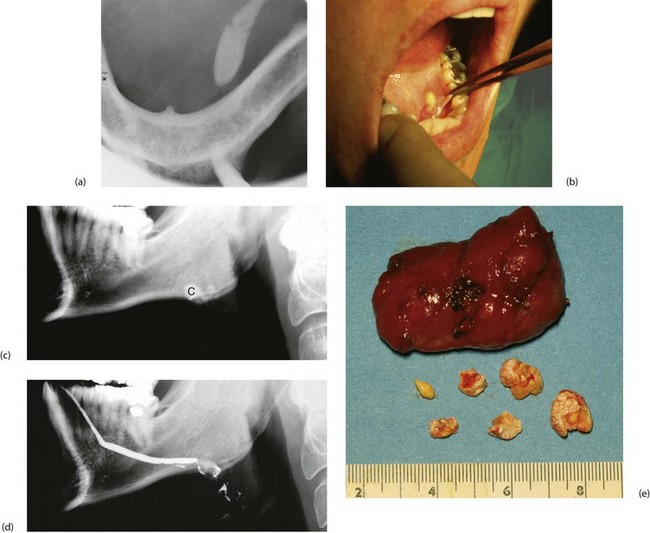

Submandibular stones may be found anywhere along Wharton’s duct (Fig. 47.4), including its course within the gland. Stones vary from several millimetres to a centimetre in diameter. Those in the distal duct tend to have an elongated ‘date stone’ shape (see Fig. 47.5a).

Clinical features

Salivary calculi rarely cause complete obstruction but the patient usually experiences intermittent swelling or pain at mealtimes when salivary flow is high. The swelling then subsides over the next hour or so. Acidic foods such as lemon juice stimulate rapid salivary flow, and can be used as a test in clinic. Pain is not usually a prominent feature; rather, patients describe a sensation of fullness. Salivary calculi occasionally present with acute or chronic bacterial infection (sialadenitis). Secondary infection in the obstructed system leads to rapidly worsening symptoms and even spreading cellulitis of the floor of the mouth (Ludwig’s angina, Fig. 47.6).

Management of salivary calculi

Plain X-rays demonstrate most calculi. For the submandibular gland and duct, an occlusal film held between the teeth shows the floor of the mouth, and a lateral oblique gives a second viewpoint. For the parotid, AP and lateral views are often used. Contrast radiography of the ducts (sialography) is sometimes indicated if the history suggests stone disease yet no stone is palpable or visible on plain X-ray, although this has largely been replaced by ultrasound. Sialography (Fig. 47.7) requires cannulation of the salivary duct which may reveal a stenosis of the orifice and may relieve symptoms temporarily. Stenosis alone of any part of the duct may produce symptoms similar to calculus obstruction.

The anterior two-thirds of the submandibular duct lie in the floor of the mouth and calculi here are removed via an intraoral (Fig. 47.5a) approach. Immediately before operation, the stone should be confirmed to be present by palpation or X-ray. Operation may be performed under local or general anaesthesia. A longitudinal incision is made in the duct over the stone and the stone lifted out. If the stone is impalpable, the duct is incised from the orifice backwards and the stone removed with forceps. The incision is not sutured but left open to improve salivary drainage. Stones can also be removed endoscopically or destroyed by lithotripsy.

Less commonly, calculi lie within the gland where they are often multiple (Fig. 47.5c–e). The usual treatment is to excise the entire submandibular gland via an incision below the mandible, placed to avoid damaging the mandibular branch of the facial and avoiding the hypoglossal nerve.

Inflammatory disorders of salivary glands

Lymph node disorders of the head and neck

Patients are often referred to a surgeon for biopsy of an enlarged cervical lymph node, often with no other symptoms or signs. Isolated lymph node enlargement may be caused by local disease in its field of drainage. Examples of local disorders include tonsillitis or dental infection, tonsillar tuberculosis or a malignant oropharyngeal tumour. Nodes draining a bacterial infection may themselves suppurate, sometimes after the primary disorder has disappeared (see Fig. 47.8). Enlarged nodes may be part of a systemic lymphadenopathy caused by glandular fever, lymphoma or HIV. Thus, any patient presenting with an enlarged lymph node requires general examination as well as of the head, neck and mouth. The latter often includes endoscopy of the pharyngeal area, usually by a specialist ENT surgeon (otorhinolaryngologist).

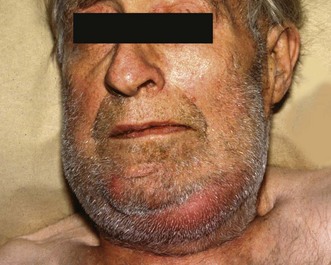

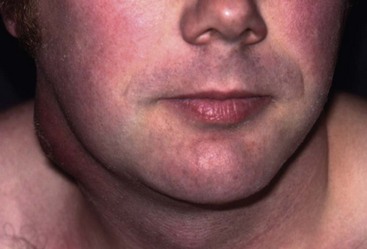

Fig. 47.8 Suppurating lymph node in the neck

This patient presented with a suppurating node in the neck which required external drainage. The primary site of sepsis was a dental abscess on a lower molar tooth

Secondary (metastatic) tumours

• Squamous carcinoma or melanoma of the skin of neck, face, scalp and ear

• Squamous carcinoma of mouth and tongue

• Squamous carcinoma of nasopharynx, oropharynx, larynx and paranasal sinuses. Note the primary tumour may be exceedingly small

• Adenocystic carcinoma of major or accessory salivary glands

• Papillary (and occasionally medullary) carcinomas of the thyroid

In contrast, tumours from the chest or abdomen usually metastasise to the lower part of the posterior triangle, particularly to Virchow’s node (Fig. 47.9), lying deeply in the angle between sternocleidomastoid and clavicle on the left side.

Miscellaneous causes of a lump in the neck

Branchial cysts, sinuses and fistulae

The embryological origin of these is disputed but they probably arise from remnants of the second pharyngeal pouch or branchial cleft. Branchial cysts usually present in early adulthood but sometimes later (Fig. 47.10). Such late presentation is unusual for congenital lesions generally. The patient typically complains of a painless swelling in the side of the neck which varies in size. Some present with a sudden painful red swelling due to inflammation of a previously unnoticed cyst.