Lumps, Bumps, and Hamartomas

Julie S. Prendiville

Lumps and bumps

A wide variety of conditions affecting the skin and subcutaneous tissues present as papulonodular lesions, or ‘lumps and bumps.’ Benign and malignant neoplasms, hamartomas, and inflammatory and infectious disorders, as well as a number of infiltrative diseases, can be included in this category. Some of these conditions are discussed in detail in other chapters. This section deals with a group of nonmalignant disorders that present as discrete, circumscribed skin lesions or hamartomas in newborns and young infants.

Fibromatoses

The fibromatoses represent a diverse collection of mesenchymal tumors characterized by fibroblastic–myofibroblastic proliferation.1 They are locally invasive neoplasms that do not metastasize but which may recur following surgical excision. They vary in clinical behavior, from benign lesions that regress spontaneously to aggressive life-threatening tumors. They can be solitary or multifocal, and may exhibit skin, soft tissue, bone, or visceral involvement. Most of these tumors are sporadic, but some occur in a familial setting.

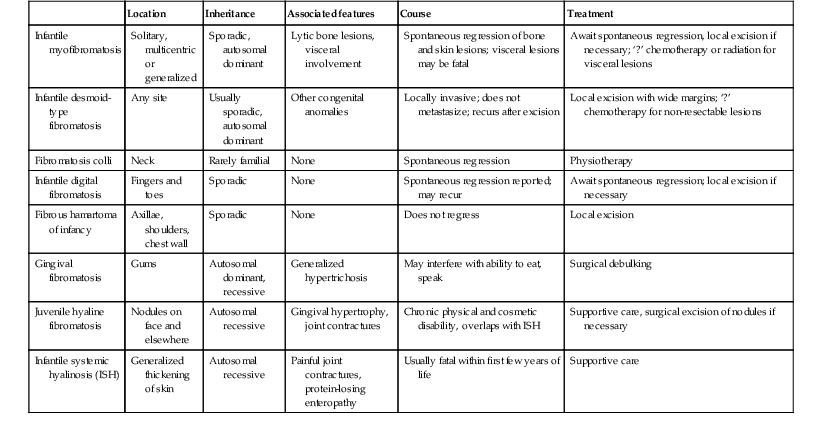

The fibromatoses are classified as juvenile or adult (Box 26.1).1 The juvenile fibromatoses are a unique group of fibroblastic–myofibroblastic proliferations that present at birth or in the first years of life (Table 26.1), accounting for approximately 12% of pediatric soft tissue tumors.1 Adult-type fibromatoses are occasionally observed in infancy and childhood.1 The fibromatoses have also been subdivided according to the site of fibrous tissue overgrowth into superficial or fascial, and deep or musculoaponeurotic (desmoid type).2

TABLE 26.1

Juvenile fibromatoses

| Location | Inheritance | Associated features | Course | Treatment | |

| Infantile myofibromatosis | Solitary, multicentric or generalized | Sporadic, autosomal dominant | Lytic bone lesions, visceral involvement | Spontaneous regression of bone and skin lesions; visceral lesions may be fatal | Await spontaneous regression, local excision if necessary; ‘?’ chemotherapy or radiation for visceral lesions |

| Infantile desmoid-type fibromatosis | Any site | Usually sporadic, autosomal dominant | Other congenital anomalies | Locally invasive; does not metastasize; recurs after excision | Local excision with wide margins; ‘?’ chemotherapy for non-resectable lesions |

| Fibromatosis colli | Neck | Rarely familial | None | Spontaneous regression | Physiotherapy |

| Infantile digital fibromatosis | Fingers and toes | Sporadic | None | Spontaneous regression reported; may recur | Await spontaneous regression; local excision if necessary |

| Fibrous hamartoma of infancy | Axillae, shoulders, chest wall | Sporadic | None | Does not regress | Local excision |

| Gingival fibromatosis | Gums | Autosomal dominant, recessive | Generalized hypertrichosis | May interfere with ability to eat, speak | Surgical debulking |

| Juvenile hyaline fibromatosis | Nodules on face and elsewhere | Autosomal recessive | Gingival hypertrophy, joint contractures | Chronic physical and cosmetic disability, overlaps with ISH | Supportive care, surgical excision of nodules if necessary |

| Infantile systemic hyalinosis (ISH) | Generalized thickening of skin | Autosomal recessive | Painful joint contractures, protein-losing enteropathy | Usually fatal within first few years of life | Supportive care |

Infantile myofibromatosis

The term infantile myofibromatosis was introduced by Chung and Enzinger3 in 1981 to designate a disorder previously described under numerous synonyms, including congenital multiple fibromatosis, diffuse congenital fibromatosis, multiple congenital mesenchymal tumors, and multiple vascular leiomyomas of the newborn. There are three clinical patterns of presentation: solitary infantile myofibroma; multicentric infantile myofibromatosis, with multiple lesions in the skin, soft tissues, and bone; and generalized infantile myofibromatosis, in which there is also visceral involvement.1

Cutaneous findings.

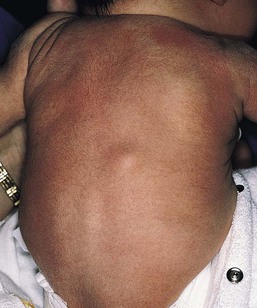

Over 80% of myofibromas present in the first 2 years of life, and 60% are apparent at birth or shortly thereafter.3,4 Lesions may be superficial or deep, involving the skin, subcutaneous tissues, and muscle. They appear clinically as discrete, rubbery, firm to hard nodules measuring from 0.5 to 8 cm in diameter (Fig. 26.1). Cutaneous myofibromas may be skin-colored or have a prominent vascular appearance, resembling hemangioma. Sites of predilection for solitary lesions are the head, neck, trunk, and upper extremities. In the multicentric and generalized forms there are multiple and widespread myofibromas, numbering from a few to over 100 (Fig. 26.2).5 Skin and soft tissue lesions are asymptomatic and usually cause little morbidity. Rarely, a myofibroma presents with surface ulceration or an atrophic morphology (Fig. 26.3).4,6 Joint contractures have been observed with extensive limb lesions.7

Extracutaneous findings.

In the multicentric form of the disease, myofibromas in the skin and soft tissues are associated with multiple lytic bone lesions. These may be extensive and can involve any bone.5 Progression in size and number has been observed during infancy.5 The bone tumors eventually stabilize, and spontaneous healing occurs with complete regression during the first few years of life. The development of sclerotic borders around lytic areas may be an early sign of regression.5 In most cases, there are no clinical signs or symptoms of bone disease. Pathologic fractures may occur rarely and usually heal without residual deformity.5,8 Vertebral body collapse has been described, with residual loss of vertebral height in early childhood.5 There are reports of spinal cord compression resulting from solitary or multicentric lesions involving the spinal canal.9 Solitary infantile myofibroma may also occur in the orbit.10

The much rarer generalized form of infantile myofibromatosis is characterized by involvement of visceral organs in addition to skin, soft tissue, and bone tumors. The gastrointestinal tract, heart, and lungs are most frequently affected. Involvement of the central nervous system is rare. Myofibromatosis in visceral organs is locally invasive and may severely compromise organ function. Cardiopulmonary, gastrointestinal, and hepatobiliary complications can be fatal, particularly in the newborn period or early infancy.11 There have been two reports of associated aneurismal dilatations of arteries as observed in fibromuscular dysplasia.12

Multiple skin and soft tissue tumors may occasionally occur in the absence of bone or visceral involvement.1 Conversely, bone involvement has been observed in association with a single soft tissue lesion,11 or in the absence of skin lesions.5

Etiology and pathogenesis.

The pathogenesis is unknown. Most cases are sporadic. Familial occurrence is associated with autosomal dominant inheritance.13

Diagnosis.

Myofibromatosis may be suspected by the presence of firm, cutaneous and subcutaneous nodules. A biopsy is required to confirm the diagnosis. All three forms of infantile myofibromatosis show interlacing fascicles of spindle-shaped fibroblasts.1 Central vascular areas resembling hemangiopericytoma are variably present. Focal necrosis, calcification, hyalinization, macrophages containing hemosiderin, and chronic inflammation may be seen.1 A giant cell variant containing multiple multinucleated giant cells has also been described. There is positive immunoreactivity for vimentin and actin, consistent with the presumed myofibroblastic derivation of the tumor; desmin staining is variable. Electron microscopy shows cells with features of both fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells.

Infants with cutaneous myofibromas should be evaluated for bone and visceral involvement, particularly when there are multiple lesions. Recommended initial investigations include a skeletal survey, chest X-ray, echocardiogram, and abdominal imaging studies.11

Differential diagnosis.

Infantile myofibromatosis can be distinguished from other pediatric soft tissue tumors by histopathologic examination of biopsy material. These include other forms of fibromatosis, as well as congenital fibrosarcoma, leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma, neurofibroma, metastatic neuroblastoma, hemangioma, hemangiopericytoma, chondromatosis, stiff skin syndrome, and nodular fasciitis.1

Treatment and prognosis.

The prognosis for infantile myofibromatosis is good in the absence of visceral involvement. Lesions in the skin and soft tissues show spontaneous involution during the first few years of life, sometimes leaving residual areas of skin atrophy or hyperpigmentation (Fig. 26.4). Bone lesions also regress spontaneously, usually without significant disability or residual radiologic change. They do not interfere with enchondral bone growth.5 The prognosis is grave for newborns with visceral disease, in whom a mortality rate of 76% has been documented.11

Surgical excision may be necessary to obtain tissue for diagnosis. Otherwise, excision should be limited to lesions that result in functional impairment or severe cosmetic disability.7,11 The role of chemotherapy or radiation for symptomatic, recurrent, or nonresectable disease is not established. Successful treatment of life-threatening generalized infantile myofibromatosis and multicentric disease using low-dose chemotherapy has been reported.14

Infantile desmoid-type or aggressive fibromatosis

Although desmoid fibromatosis has traditionally been considered a deep fibromatosis of adulthood, with abdominal, intra-abdominal, and extra-abdominal variants, a specific juvenile subset is recognized.1 Description of this entity under a variety of synonyms, including among others aggressive fibromatosis of infancy, musculoaponeurotic fibromatosis, desmoma, and fibrosarcoma grade 1 desmoid type, has led to confusion in the literature.15 Up to 30% of juvenile desmoid tumors present in the first year of life, and congenital cases have been reported.1,16

Clinical findings.

Infantile desmoid-like or aggressive fibromatosis involves deep tissues and is generally extra-abdominal.1 The usual clinical presentation is a slowly growing, nontender subcutaneous mass that has been present for weeks or months (Fig. 26.5). Sites of predilection in children are the head and neck, extremities, shoulder girdle, trunk, and hip regions. The abdomen, retroperitoneum, spermatic cord, and breast may also be involved. Rarely, there are multiple lesions. The tumor tends to be very locally aggressive, with infiltration of adjacent skeletal muscles, tendons, or periosteum, and erosion of bone.

Approximately 12% of pediatric patients with desmoid fibromatosis have other congenital abnormalities.1 Adult-type intra-abdominal desmoid tumors are associated with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and Gardner syndrome.1,17 Although most tumors in children are sporadic, there are reported cases of associated Gardner syndrome in childhood, one of which presented in infancy.18–20

Etiology and pathogenesis.

The finding of minor radiologic bone abnormalities in 80% of patients with desmoids and 48% of their relatives suggests an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance.1 Antecedent trauma, including surgery or irradiation, is reported in 12–63% of patients with all forms of desmoid tumor.1 It is postulated that desmoid tumors are associated with a familial defect in the regulation of connective tissue and may be precipitated by multiple factors.1,17,21 Desmoid fibromas in adults and children can be associated with mutations in the adenomatosis polyposis coli (APC) or β-catenin CTNNB1 genes.22

Diagnosis.

The tumor is composed of bundles of slender, uniform spindle cells surrounded by variable amounts of collagen. Cleft or slit-like blood vessels are variable in number and more abundant at the periphery. The fibrous proliferation may be indistinguishable from scar tissue, except that it infiltrates skeletal muscle and tendons. Cellularity is variable. Some childhood lesions have an increased number of mitoses and greater cellularity.1 Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies show that the lesion is composed of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. Immunohistochemistry and genotyping may help to distinguish sporadic from FAP cases.22

Differential diagnosis.

Myofibromatosis and other juvenile fibromatoses should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Keloid scars are more superficial than desmoid tumors. Cellular variants must be distinguished histopathologically from fibrosarcoma.

Treatment and prognosis.

Local excision with wide margins, if possible, is the mainstay of treatment.16–19,23 The recurrence rate varies from 30–80%.1 Higher recurrence rates are associated with a young age at diagnosis, large lesions, intralesional or marginal excision, and intra-abdominal location. Microscopic features of high vascularity, myxoid foci, and abundant immature myofibroblasts are associated with a higher recurrence rate.1 Treatment with combination chemotherapy and radiotherapy, or with tamoxifen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, has been advocated for nonresectable, symptomatic or progressive disease.19,24 Mortality from locally aggressive desmoids is less than 10%.1

Fibromatosis colli

Fibromatosis colli, also known as sternocleidomastoid pseudotumor of infancy or congenital muscular torticollis, is a congenital fibromatosis of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. It occurs in up to 0.4% of live newborns.1 Males are affected more than females. It does not involve the skin.

Clinical findings.

A hard, nontender, lobulated subcutaneous mass is palpable in the lower third of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The trapezoid muscle is sometimes involved. Following an initial rapid period of growth, the tumor stabilizes in size. Torticollis and facial asymmetry are variable and may be transient. There is a right-sided predominance, and 2–3% of cases are bilateral.1

Etiology and pathogenesis.

The pathogenesis is unknown. Birth trauma has been implicated in 50% of cases, with a history of complicated delivery; whether this is a cause or an effect of the tumor is not clear. Familial cases are rare.1

Diagnosis.

Histopathologically, bands of fibroblasts with abundant collagen are intermingled with residual angulated skeletal muscle fibers. The diagnosis may be established by fine-needle aspiration, which shows benign spindle cells and degenerating skeletal muscle fibers. Ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging may also be useful.25

Differential diagnosis.

A combination of the typical location of the lesion in the neck and the characteristic histopathology is diagnostic. The clinical differential diagnosis of a neck swelling includes lymphatic malformation, hemangioma, and malignant neoplasms. The histopathologic features may resemble those of a desmoid tumor.1

Treatment and prognosis.

The majority of lesions regress within the first year of life. Most resolve completely, but minor residual asymmetry or tightening of the sternocleidomastoid muscle is seen in 25% of cases.1 Only 9% have persistence of the tumor and torticollis. Physiotherapy is the treatment of choice.26 Surgery is rarely necessary unless the diagnosis is in doubt or the mass fails to resolve.

Infantile digital fibromatosis

Infantile digital fibromatosis is a recurring myofibroblastic proliferation of the fingers and toes. Synonyms for this tumor include digital fibrous tumor of Reye, digital fibrous swelling, recurring digital fibrous tumor of childhood, and inclusion body fibromatosis.1

Cutaneous findings.

Almost all lesions are diagnosed in infancy, and one-third are present at birth. Both sexes are affected equally. The typical lesion is an asymptomatic, firm, smooth, pink nodule located on the lateral or dorsal aspect of the digit, measuring <3 cm in diameter (Fig. 26.6). Lesions are more common on the fingers than on the toes. The thumbs and great toes are spared. There is often deformity of the affected digit. There may be single or multiple nodules (Fig. 26.7). Rarely, more than one digit is involved or extradigital lesions are seen.27

Extracutaneous findings.

Periosteal attachment is not unusual, but underlying bone erosion is rare.

Etiology and pathogenesis.

The pathogenesis is not known. Defective organization of actin filaments in myofibroblasts has been hypothesized.1

Diagnosis.

Whorls and interdigitating sheets of uniform fibroblasts in a densely collagenous stroma are seen in the dermis or subcutis.1 A unique feature is the presence of distinctive, eosinophilic, perinuclear cytoplasmic inclusions surrounded by a clear halo that stain red with a trichrome stain. Electron microscopy shows abundant cytoplasmic filaments that form whorled bodies; these are the ultrastructural correlate of the cytoplasmic inclusions. Immunostaining is positive for desmin, actin, vimentin, and keratin.

Differential diagnosis.

The digital location and the characteristic histopathology distinguish this lesion from other fibromatoses and pediatric soft tissue tumors.

Treatment and prognosis.

The local recurrence rate is 60–90% following surgical excision. Many tumors regress spontaneously within a few years.27 Conservative management without surgery is appropriate, unless there is functional impairment.27 Mohs micrographic surgery to debulk the tumor has been performed.28 Successful treatment with intralesional fluorouracil injections has been reported in a 7-year-old child.29

Fibrous hamartoma of infancy

Fibrous hamartoma of infancy is a benign fibrous tumor that develops during the first 2 years of life.30 Up to 20% are present at birth.1 Occasional cases have been described in children between 2 and 10 years. Males are affected more frequently than females.

Cutaneous findings.

Fibrous hamartoma presents as a subcutaneous lesion located around the axillae, shoulders, and upper chest wall.31 It may involve other sites, such as the inguinal region, extremities, and head and neck. It is usually a solitary nodule, measuring 2–5 cm in diameter, that feels lumpy to palpation. There may be overlying hypertrichosis. Occasionally, these lesions are multifocal. There are no symptoms.

Extracutaneous findings.

There are no systemic associations.

Etiology and pathogenesis.

Fibrous hamartoma of infancy is believed to represent a hamartomatous process rather than a true neoplasm. It is not familial.

Diagnosis.

The hamartoma is located in the subcutaneous and musculoaponeurotic tissues.30,31 Histopathologic examination reveals three characteristic elements: a fibrous component consisting of well-defined fascicles of fibroblasts or disorderly fibroblasts in a collagenous stroma; mature adipose tissue; and myxoid mesenchymal tissue in a basophilic matrix. Electron microscopy reveals the presence of both fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, primitive mesenchymal cells, small blood vessels, and mature adipocytes.1

Differential diagnosis.

The clinical differential diagnosis of fibrous hamartoma of infancy includes a macrocystic lymphatic malformation, hemangioma, and other soft tissue tumors. Identification of the three histopathologic components of this lesion distinguishes it from other fibroblastic proliferations.31 A similar hamartoma with an admixture of fat and an absence of fibromyxoid tissue is described as lipofibromatosis.32

Treatment and prognosis.

There is no tendency to spontaneous regression. The treatment of choice is surgical excision. The recurrence rate is low, even with incomplete excision.31

Lipofibromatosis

Lipofibromatosis is a rare, slowly growing tumor of fibroblasts and mature adipose tissue.1 It affects infants and young children and is congenital in up to 25% of cases. The tumor typically arises on the distal extremities and is less often encountered on the head and neck.1 Lesions range in size from 2–7 cm in diameter.

Histopathologically, there is abundant adipose tissue traversed by fascicles of fibroblasts with variable collagen and focal myxoid change. Spindle cells stain positive for smooth muscle actin.

The differential diagnosis of lipofibromatosis includes fibrolipoma, lipofibromatous hamartoma, fibrous hamartoma of infancy, lipoblastoma, and desmoid fibromatosis. Treatment is by surgical resection but the rate of recurrence or persistent growth is high.

Gingival fibromatosis

This is a rare familial disorder that manifests at the time of eruption of the deciduous or permanent teeth.

Cutaneous findings.

There is slowly progressive gingival enlargement that may cover the crowns of the teeth and result in difficulty in eating or speaking. It is associated with generalized hypertrichosis.

Extracutaneous findings.

Rarely there is associated mental retardation and epilepsy. The Zimmerman–Laband syndrome is characterized by gingival fibromatosis, hypertrichosis, intellectual disability, and absence and/or hypoplasia of the nails or terminal phalanges of the hands and feet as well as other anomalies.33

Diagnosis.

Mucosal biopsy shows coarse, interlacing collagen bundles with sparse fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. There may be calcification, ossification, abundant amorphous extracellular material, and cellular fibroblastic proliferation.

Differential diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis includes phenytoin usage, chronic gingivitis, cherubism, juvenile hyaline fibromatosis, and other rare syndromes.

Treatment and prognosis.

Treatment options include repeated surgical debulking of the gums or dental extraction.

Adult-type fibromatoses

The superficial fibromatoses of adulthood are the most common type of fibromatosis in the general population but are rare in infants and children. Fibromatosis may involve the palm (Dupuytren contracture), the plantar surface of the foot (Ledderhose disease), or the penis (Peyronie disease). Dupuytren-type fibromatosis of the palms and soles may be seen in childhood, and is occasionally congenital (Fig. 26.8![]() ).1 Surgical excision is only necessary for diagnosis or for release of contractures. Knuckle pads are seen in older children and adolescents but not in infants.

).1 Surgical excision is only necessary for diagnosis or for release of contractures. Knuckle pads are seen in older children and adolescents but not in infants.

Leiomyoma

Leiomyoma is a benign tumor of smooth muscle. Cutaneous leiomyoma may arise from the arrector pili muscle in hair follicles, the dartos muscle of the scrotum and labia majora, the erectile muscle of the nipple, and the muscular wall of veins (angioleiomyoma). Leiomyomas are uncommon in children and are extremely rare in the newborn period.37

Cutaneous findings.

Cutaneous leiomyomas appear as discrete papules or nodules with a pink or brown discoloration of the overlying skin. They are usually solitary but may be multiple. Rarely, a leiomyoma may present as a pedunculated mass at birth or as a papular plaque in early infancy.37–39 Leiomyomas are often painful, particularly on exposure to cold. Leiomyomas of the tongue are also reported.38

Extracutaneous findings.

Most cutaneous leiomyomas are not associated with visceral disease. The multiple leiomyomas of the esophagus and tracheobronchial tree in Alport syndrome may be associated with female genital leiomyomas in older children and adults.40 Leiomyomas that occur in immunocompromised children only rarely involve the skin or soft tissues.41

Etiology and pathogenesis.

Multiple cutaneous leiomyomas presenting in adolescence or adult life may be inherited as an autosomal dominant trait, but the etiology of other forms is unknown.

Diagnosis.

The diagnosis is made by skin biopsy, which demonstrates whorls and bundles of well-differentiated spindle cells with cigar-shaped nuclei in the dermis. There is a variable collagenous component. The smooth muscle stains red with the Masson trichrome stain. Immunochemistry is positive for muscle-specific actin and desmin reactivity.

Differential diagnosis.

Leiomyoma must be distinguished from the fibroblastic and myofibroblastic proliferations of infancy and childhood, as well as from other spindle cell tumors such as neurofibroma and leiomyosarcoma. Immunohistochemistry may be helpful, as myofibroblastic tumors express smooth muscle actin more than muscle-specific actin or desmin.37 The circumscribed spindle cell appearance of leiomyoma differs from the smooth muscle bundles of congenital smooth muscle hamartoma.

Treatment and prognosis.

Excision is curative for solitary lesions.

Neurofibromas and other neural tumors

Cutaneous neurofibromas in infants and young children are most frequently associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1) (see Chapter 29). These benign tumors consist of Schwann cells, nerve fibers, and fibroblasts, and may be cutaneous, subcutaneous, or plexiform. Cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibromas are rarely seen at birth but may sometimes appear within the first year of life. Plexiform neurofibromas are often present at birth and are considered pathognomonic of neurofibromatosis. There may be a large area of hyperpigmentation overlying the plexiform neurofibroma that predates the characteristic ‘bag of worms’ consistency of the tumor. These lesions enlarge with time and can cause considerable cosmetic disfigurement, particularly on the face and around the eye. A plexiform neurofibroma in the neck may compromise airway function, and large lesions over the back are often associated with underlying spinal involvement.

Schwannomas are found in both neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF-2) and in schwannomatosis. Schwannomatosis, or neurilemmomatosis, is characterized by multiple cutaneous schwannomas and can present at birth or develop during childhood.42 These lesions are a marker for development of central nervous system tumors in later childhood and adult life. Schwannomatosis is sometimes associated with SMARCB1 mutations and is distinguished from NF-2 primarily by the absence of vestibular tumors.42

Pacinian neurofibromas, or nerve-sheath myxomas, are uncommon tumors with components that resemble Vater–Pacini corpuscles.43 Multiple hairy pacinian neurofibromas have been reported in children without NF-1 and may be congenital.43 Underlying skeletal anomalies may be associated with pacinian neurofibromas in a sacrococcygeal location.

Non-langerhans’ cell histiocytoses

The non-Langerhans’ cell histiocytoses encompass a diverse group of disorders in which there is proliferation of mononuclear phagocytes other than Langerhans’ cells. Two variants, juvenile xanthogranuloma and benign cephalic histiocytosis, occur primarily in infants and young children. Other benign histiocytoses, such as papular xanthoma, xanthoma disseminatum, and generalized eruptive xanthoma, may rarely present in childhood, but are extremely unusual in infancy.44,45

Juvenile xanthogranuloma

Juvenile xanthogranuloma is a benign, self-healing, non-Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis characterized by solitary or multiple yellow-red papules and nodules in the skin and occasionally in other organs.46 Although adults may be affected, it is predominantly a disorder of infancy and early childhood. There is an increased frequency of juvenile xanthogranuloma in children with NF-1, juvenile myeloid leukemia, and urticaria pigmentosa.47,48 Juvenile xanthogranulomas have also developed in children with Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis either concurrently or at a later date.49 There are single case reports of coexistence with Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome and acute lymphoblastic leukemia.50,51

Cutaneous findings.

The typical juvenile xanthogranuloma is an asymptomatic, firm, well-demarcated papule or nodule that measures from 1 mm to 2 cm in diameter. Early lesions are pink or red in color, later changing to a distinctive yellow or orange-brown (Fig. 26.9). There may be overlying telangiectasia with a purpuric appearance, and occasionally surface ulceration and bleeding with associated pruritus and discomfort. Solitary lesions with a hyperkeratotic surface, pedunculated or plaque-like morphology are also reported.46 As many as 17% of juvenile xanthogranulomas are present at birth, and 70% develop within the first year of life.46 The majority are solitary lesions. Multiple lesions may be few or number in the hundreds (Fig. 26.10A). They can be located at virtually any body site, but are most common on the head, neck, and upper trunk.

Juvenile xanthogranulomas may be classified as micronodular, measuring 2–5 mm, or macronodular, measuring 0.5–2 cm in diameter. An unusual variant is the giant juvenile xanthogranuloma, which measures from 2–10 cm in diameter (Fig. 26.10B).52 These lesions are congenital or appear in early infancy and may have a greater propensity to ulcerate. Rarely, numerous micronodular lesions may present as a generalized lichenoid eruption.53

Extracutaneous findings.

Extracutaneous juvenile xanthogranuloma is rare, and less than 50% of these patients have associated cutaneous lesions.54 The most frequent extracutaneous sites are the eye and orbit, central nervous system, liver/spleen, lung, oropharynx, and muscle. In contrast to cutaneous lesions, a systemic juvenile xanthogranuloma may produce symptoms related to a mass effect or infiltration of the involved organ. The incidence of ocular disease in patients with cutaneous lesions is 0.3–0.4%.55 Eye lesions manifest as an asymptomatic mass on the iris, unilateral glaucoma, spontaneous hyphema, or color change of the iris. Risk factors for eye involvement include multiple lesions, age <2 years, and recently diagnosed disease.55

Juvenile xanthogranulomas are seen with increased frequency in patients with NF-1. A triple association between juvenile chronic myeloid leukemia, juvenile xanthogranulomas, and NF-1 is recognized (Fig. 26.11![]() ).47

).47

Diagnosis.

The typical histopathologic appearance consists of a dense dermal infiltrate of foamy histiocytes with Touton giant cells. There is an admixture of other cell types, including lymphocytes, eosinophils, neutrophils, and foreign body giant cells, as well as infrequent mitoses. In early lesions, there may be few or absent foam cells or Touton giant cells, with a variable number of spindle cells and numerous mitotic figures.59 Immunohistochemistry shows negative staining for S100 and CD1a, and positive staining for factor X111a, CD68, CD163, fascin and CD14.56 There are no Birbeck granules visible on ultrastructural examination.

Differential diagnosis.

Distinguishing a small juvenile xanthogranuloma from clinically similar lesions such as xanthoma, mastocytoma, Spitz nevus, and other benign skin tumors may require a skin biopsy. Giant lesions may be mistaken for a hemangioma or malignant tumor. Early lesions that lack the characteristic lipid-laden histiocytes and Touton giant cells may resemble Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis on histopathologic examination.56,59 The absence of Birbeck granules and negative staining for S100 is characteristic of juvenile xanthogranuloma.

Treatment and prognosis.

Most cutaneous lesions resolve spontaneously over months or years and do not require treatment. Ulcerating, symptomatic, or large unsightly lesions may require surgical excision. A residual area of hyperpigmentation or anetoderma-like atrophy may persist. Ocular and systemic lesions can be more problematic and involvement of the liver and bone marrow can be life-threatening.60 Treatment options include observation, corticosteroids, surgical excision, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy.46,60

Benign cephalic histiocytosis

Benign cephalic histiocytosis is a non-Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis characterized clinically by multiple brownish-yellow macules and papules on the face and adjacent areas. Some authors believe that benign cephalic histiocytosis is a variant of micronodular juvenile xanthogranuloma.61,62

Cutaneous findings.

Lesions first appear between the ages of 2 months and 2 years. The face is the site of predilection, but the scalp, neck, and ears can also be involved. Lesions may be scattered over the shoulders and upper arms. Typical lesions are slightly raised, asymptomatic papules measuring 2–3 mm in diameter that vary from erythematous to light-brown or yellowish in color (Fig. 26.12![]() ). The mucous membranes are not involved.

). The mucous membranes are not involved.

Extracutaneous findings.

Typically, extracutaneous disease is absent, but there has been one report of associated diabetes insipidus.63

Diagnosis.

Histopathologically, a monomorphous histiocytic infiltrate is located in the upper and mid-dermis. There may also be a few lymphocytes and eosinophils. Foamy macrophages and Touton giant cells are typically absent. Staining for S100 protein is usually negative.64 Electron microscopy reveals coated vesicles and comma- or worm-shaped bodies. Birbeck granules are absent.

Differential diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis includes juvenile xanthogranuloma, Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis, and cutaneous mastocytosis. The lesions of mastocytosis have a similar color but urticate when rubbed (Darier sign) and have a distinctive histology. Benign cephalic histiocytosis can be distinguished from Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis by immunohistochemical stains and the absence of Birbeck granules on electron microscopy.

Treatment and prognosis.

There is no effective treatment. The skin lesions regress spontaneously over months to years. There may be residual hyperpigmentation and anetoderma-like atrophy.

Calcifying disorders of the skin

Calcium deposition in the skin, or calcinosis cutis, is found in a diverse group of disorders. It is termed dystrophic calcification when calcium is deposited in abnormal or injured tissue in patients with no abnormality of calcium or phosphate metabolism. Metastatic calcification develops in normal tissues as a result of abnormal calcium and phosphorus metabolism. Idiopathic calcification occurs in the absence of any discernible tissue injury or metabolic abnormality. Iatrogenic calcification may develop as a complication of calcium infusions or the application of calcium-containing paste to abraded skin. Cutaneous ossification, in which normal bone is formed in the dermis and subcutaneous soft tissues, is termed osteoma cutis.

Dystrophic calcification

Dystrophic calcification arises at sites of skin trauma or in association with inflammatory lesions, connective tissue disorders, skin tumors, and cysts. Calcinosis cutis on the heels is a not uncommon sequela of drawing blood by heel sticks during the neonatal period.65,66 It presents some months later as one or more white papules or nodules, and usually resolves spontaneously by 18–30 months of age. Calcification may also occur in association with subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn.67,68 Calcium deposition has been observed histopathologically both in the septa and within the fat lobules.67,69 Widespread subcutaneous calcification may develop in cases of subcutaneous fat necrosis complicating hypothermic cardiac surgery.68–70 Although hypercalcemia is a known complication of subcutaneous fat necrosis, the majority of reported cases of soft-tissue calcification have occurred in normocalcemic patients. Conversely, most infants with subcutaneous fat necrosis and hypercalcemia do not show evidence of calcium deposition in biopsies taken from affected sites.68

Dystrophic calcification has been reported in the skin lesions of a newborn infant with intrauterine-acquired herpes simplex infection.71 The calcification was present at birth and appeared to have developed in utero. A lethal disorder characterized by extensive congenital skin necrosis and follicular calcification has been described in three newborn females.72 Dystrophic calcification may also occur as a complication of intralesional corticosteroid injection of infantile periocular hemangiomas.73

Metastatic calcification

Metastatic calcification occurs when calcium salts are precipitated in normal tissues as a result of high serum calcium or phosphate levels. The calcium deposits usually consist of hydroxyapatite crystals. This is associated primarily with chronic renal insufficiency, in which ulceration of the skin may be caused by calcification of blood vessels, leading to ischemic skin necrosis, or by painful disseminated calcification of the dermis and subcutaneous tissues (calciphylaxis).74 Chronic renal failure is also associated with benign nodular calcification. Cutaneous calcium deposits may develop as a result of hypervitaminosis D, milk-alkali syndrome, and other causes of hypercalcemia and hyperphosphatemia.

Metastatic calcinosis in the skin is rarely seen in infancy and childhood.75 In contrast, the cutaneous bone formation, or osteoma cutis, associated with Albright hereditary osteodystrophy frequently appears first in infancy or childhood and may present in the neonatal period. This metabolic disorder is discussed below.

Idiopathic calcification

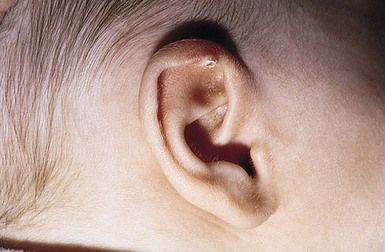

Idiopathic calcification can be congenital or acquired. Congenital calcified nodules occur most frequently on the ear, but may be seen elsewhere on the face and limbs. These lesions are variously described as congenital calcified nodule of the ear, subepidermal calcified nodule, or solitary congenital nodular calcification of Winer.76–78 Other types of idiopathic calcinosis cutis, such as idiopathic calcification of the scrotum or vulva, and the milia-like lesions associated with Down syndrome, present later in childhood or adolescence and are not seen in the newborn. There are rare reports of juxta-articular tumoral calcinosis in infancy.79–82

Calcified ear nodule

A solitary calcified nodule on the pinna or earlobe is the most common presentation of idiopathic calcinosis in the newborn (Fig. 26.13). These nodules may occur elsewhere on the face or limbs, and occasionally there is more than one. Auricular lesions developing after birth have also been described. There is a male preponderance.

Cutaneous findings.

The nodule is firm and measures 3–10 mm in diameter. The surface may be warty in appearance, or smooth and dome-shaped. The color is chalky white or yellow. Surface ulceration and discharge of calcified material may occur spontaneously or as a result of trauma. There are usually no associated symptoms.

Extracutaneous findings.

Serum calcium and phosphate levels are normal. There are no systemic abnormalities.

Etiology and pathogenesis.

The pathogenesis of these lesions is not clear. Most authors believe they represent dystrophic calcification following dermal damage from some unknown source. Proposed hypotheses include derivation from milia, syringomas, other sweat gland hamartomas, nevi, trauma, and ischemic injury.77,78

Diagnosis.

The diagnosis is often made on the clinical appearance. Histopathologically, amorphous and/or globular masses of calcified material are seen in the papillary dermis and may extend to the reticular dermis. Foreign body giant cells may be observed in association with the calcified masses. The overlying epidermis shows a warty architecture with variable amounts of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. Ulceration and transepidermal elimination of calcium may occur.

Differential diagnosis.

Clinically, calcified nodules may be misdiagnosed as viral warts, molluscum contagiosum, pilomatricomas, syringomas, and congenital inclusion cysts.

Treatment and prognosis.

If treatment is necessary, the nodule can be removed by curettage or excision. Calcified nodules sometimes recur following curettage or shave excision. Intralesional injection of triamcinolone at the time of shave excision has been suggested for recurrent lesions.76

Tumoral calcinosis

Tumoral calcinosis is characterized by painless, calcified soft tissue nodules located close to large joints in otherwise healthy children and adults.79–82 It may affect several family members and occurs most frequently in patients of African or Middle-Eastern descent. There have been reports of tumoral calcinosis presenting in infancy, and two in the neonatal period.81,83,84

Cutaneous findings.

Tumoral calcinosis presents as progressively growing, lobulated masses in a juxta-articular location. The hip joints, shoulders, and elbows are most frequently affected in older children and adults. A predilection for the anterior aspect of the knee has been noted in three infants.81 Involvement of the buttock, axilla, and supraclavicular region has also been observed in infancy.82 Lesions may be multifocal and occasionally bilateral. Rarely, ulceration of the overlying skin with discharge of a chalky-white substance may occur.80 Large lesions may interfere with joint or muscle function.

Extracutaneous findings.

One subtype of tumoral calcinosis is associated with idiopathic hyperphosphatemia. Transient and marginally elevated serum phosphate levels were found in an affected infant.81 Serum calcium levels are normal.

Etiology and pathogenesis.

Familial tumoral calcinosis with hyperphosphatemia has been linked to mutations in the GALNT3 gene on chromosome 2q24, to the KL gene, encoding Klotho, and to the fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF-23) gene.84 Normophosphatemic familial tumoral calcinosis is linked to SAMD9 mutations. Both subtypes have an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance.84

Diagnosis.

Radiographs show discrete, sometimes lobulated, calcified areas. There is no joint involvement, and the underlying bones appear normal. Excisional biopsy specimens usually show a well-encapsulated calcified mass, but there may be invasion of the surrounding musculature. Histopathologic examination reveals calcification, central necrosis, a chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate including multinucleate giant cells, and fibrosis.79,81

Treatment.

Excision is the treatment of choice, but there may be recurrence after excision. Spontaneous resolution was observed in one infant after incisional biopsy of a supraclavicular mass.82

Iatrogenic calcification

Iatrogenic calcinosis cutis (see Chapter 8) may result from intravenous infusion of calcium gluconate, with or without extravasation of the solution into the tissues. In addition to cutaneous calcification there may be an intense inflammatory response and occasionally soft tissue necrosis.85

Iatrogenic calcification has also been described following electrode placement for electroencephalography, electromyography, and brainstem auditory evoked potentials when calcium-containing electrode paste was applied to abraded skin.86 Treatment is generally symptomatic, and resolution occurs spontaneously over several months.

Osteoma cutis

Osteoma cutis is caused by heterotopic differentiation of osteoblasts in the dermis. It is classified as primary and secondary. In primary osteoma cutis there is no pre-existing skin pathology. In secondary osteoma cutis bone formation develops within scars, inflammatory lesions, skin tumors, hamartomas, or cysts.

Primary osteoma cutis may present in infancy as a manifestation of pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1 (PHP1), pseudopseudohypoparathyroidism (PPHP), or progressive osseous heteroplasia (POH).87,88 Congenital plate-like osteoma cutis (POC)89 and reported cases of familial ectopic ossification or hereditary osteoma cutis may be related variants.90

Pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1 and Albright hereditary osteodystrophy

Pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1 (PHP1) is characterized by a lack of end-organ responsiveness to parathormone and variable degrees of hypocalcemia and hyperphosphatemia. PHP1 can be associated with the phenotype of Albright hereditary osteodystrophy (AHO), a related clinical syndrome associated with PHP1 or PPHP. PPHP patients have the phenotype of AHO but serum calcium and phosphate levels are normal. Both PHP1 and PPHP may occur in the same kindred, although not in the same sibship.87

Cutaneous findings.

Osteoma cutis is present in up to 42% of patients with PHP1 and PPHP. Lesions are usually first noted in infancy or childhood. They may be located anywhere on the body and have a predilection for sites of friction or mild trauma. The characteristic lesions are blue-tinged, stone-hard papules, nodules, or plaques that range in size from pinpoint to 5 cm in diameter (Fig. 26.14). Early lesions may present as blue or erythematous macules (Fig. 26.15![]() ). Rarely, more extensive or deeper cutaneous ossification or POH may develop (Fig. 26.16

). Rarely, more extensive or deeper cutaneous ossification or POH may develop (Fig. 26.16![]() ). Ulceration occurs occasionally.

). Ulceration occurs occasionally.

Extracutaneous findings.

The characteristic phenotype of AHO includes short stature, round face, obesity, and brachydactyly, in particular a shortened fourth metacarpal. Other manifestations include dental defects, short broad nails, cataracts, calcification of the basal ganglia, and variable degrees of mental retardation. These findings are easier to discern in late childhood and adulthood than in infancy. Hypocalcemia may result in seizures and tetany. Most patients with PHP1 have thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) resistance and hypothyroidism may occasionally present in the neonatal period. Hypogonadism and growth hormone resistance may also occur.

Etiology and pathogenesis.

The metabolic changes in PHP result from a failure of receptors in renal and skeletal target tissues to respond to PTH. This resistance to the action of PTH is variable in PHP and absent in PPHP. End-organ resistance to PTH in PHP1 is associated with reduced expression or function of a guanine nucleotide stimulatory protein (Gs-α) that is required for activation of adenylate cyclase by the hormone-bound receptor.87 This protein is encoded by the GNAS1 gene located on chromosome 20q13. Inheritance is by autosomal dominant transmission. AHO with hormone resistance (PHP1) occurs only with maternal transmission of the genetic defect, whereas paternal imprinting results in PPHP or POH.91 The reason for development of cutaneous ossification is unclear but may relate to differentiation of dermal mesenchymal cells into osteoblasts.92

Diagnosis.

Skin histopathology shows bone formation in the dermis and subcutis. Osteoblasts, osteocytes, and osteoclasts are present within the spicules of bone. When ossification is severe and progressive, a proliferation of spindle cells, resembling fibroblasts, may be prominent.

In PHP there is hypocalcemia, hyperphosphatemia, and an elevated serum PTH. In PPHP there is no discernible abnormality of calcium and phosphate metabolism. Urinary excretion of cAMP in response to intravenous infusion of PTH is impaired in most cases of PHP1, but is normal in PPHP.

Radiologic abnormalities include ossification of the skin and subcutaneous tissues; shortening of the metacarpal, metatarsal, and phalangeal bones, notably the distal phalanx of the thumb and the fourth metacarpal; and cone epiphyses. Occasionally, there may be radiographic evidence of hyperparathyroidism or osteomalacia.

Differential diagnosis.

Hypocalcemia, hyperphosphatemia, and elevated levels of circulating PTH in the absence of renal disease, steatorrhea, and generalized osteomalacia are characteristic of PHP1. A diagnosis of PPHP may be difficult to establish in infancy, particularly when there is no family history of AHO. The differential diagnosis includes POH, congenital plate-like osteoma cutis, and familial osteoma cutis in families without evidence of AHO.90

Treatment and prognosis.

Treatment of PHP is directed towards controlling hypocalcemia by careful administration and monitoring of calcium and vitamin D. Normocalcemic patients must be monitored closely and evaluated regularly for the development of cataracts or hypocalcemia. Mental retardation may be causally related to poorly-controlled or undetected hypocalcemia. Patients should also be screened for hypothyroidism. There is no effective treatment for osteoma cutis. Surgical excision may be considered for individual lesions that cause pain or cosmetic disfigurement.

Progressive osseous heteroplasia

Progressive osseous heteroplasia (POH) is characterized by progressive heterotopic ossification of the skin and deeper soft tissues, including muscle.88,92,93 It presents at birth or in early infancy with focal areas of dermal ossification that enlarge and coalesce to form larger nodules and plaques. Extension to the subcutaneous tissues and muscle often results in ankylosis of affected joints and growth retardation of involved limbs. There have been case reports of ossification limited to one half of the body or to a single limb.93,94 Histopathologic examination reveals mainly intramembranous ossification similar to that seen in AHO, although foci of enchondral bone formation with cartilage are sometimes present. There is a female preponderance. POH may be sporadic or inherited as an autosomal dominant trait with phenotypic variability.92 Familial cases have been linked to GNAS1 mutations inherited exclusively from the father.91,95

POH is not associated with endocrine dysfunction or the skeletal and developmental abnormalities of Albright hereditary osteodystrophy. The heterotopic ossification in AHO is usually more superficial and limited to the dermis and subcutis. However, the clinical phenotype of POH is observed in families with AHO (Fig. 26.16![]() ).96 The relationship of AHO to POH and other forms of osteoma cutis awaits further understanding of mutations in the GNAS1 gene and their effects on osteogenic differentiation in the skin and soft tissues.97

).96 The relationship of AHO to POH and other forms of osteoma cutis awaits further understanding of mutations in the GNAS1 gene and their effects on osteogenic differentiation in the skin and soft tissues.97

Congenital plate-like osteoma cutis

Congenital plate-like osteoma cutis (POC) is a rare entity that occurs in infants with no abnormality of calcium or phosphate metabolism.89 Lesions present at birth or in the first year of life as a large, asymptomatic, skin-colored plaque, varying in size from 1–15 cm. There are no predisposing events such as trauma or infection to explain the heterotopic ossification. The scalp is the site of predilection, but lesions may also be found on the limbs or trunk. There are no associated abnormalities. Radiographs reveal calcified sheets or nodules in the subcutaneous soft tissues. Histopathology shows mature spongy bone in the dermis and subcutis. There may be gradual progression of the lesion with time and clinical overlap with POH. It is proposed that the term congenital plate-like osteoma cutis should be reserved for nonprogressive, superficial lesions to distinguish this disorder from POH in which ossification extends deeper into muscle and is relentlessly progressive.88 GNAS1 mutations have been reported suggesting it may be a variant of POH.89 Treatment is by excision, if necessary and feasible. Recurrence after excision has been reported.

Pilomatricoma

Pilomatricoma, previously known as calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe, is a benign adnexal tumor derived from hair matrix cells. It commonly appears in children in the first decade of life and may be seen in infancy.98,99 Familial occurrence is documented and it can be associated with myotonic dystrophy or Gardner syndrome and familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP).100,101 There is a slight female preponderance.99

Cutaneous findings.

The pilomatricoma presents clinically as a slowly enlarging, hard nodule that is fixed to the skin but freely mobile over the underlying tissues. The overlying skin may be white, skin-colored, or have a blue-red discoloration. The size varies from 0.1–6 cm in diameter, with an average of about 1 cm.99 Ulceration of the overlying skin occurs rarely, with discharge of a white chalk-like material, and rapid enlargement due to bleeding within the lesion has been described.102 Pilomatricomas are seen most commonly on the head and neck (Figs 26.17, 26.18), but also appear on the trunk and extremities (Fig. 26.19). They are usually solitary, but multiple and recurrent pilomatricomas are well recognized and may be seen in otherwise healthy children. Multiple lesions are reported in myotonic dystrophy, Gardner syndrome and FAP, the Rubinstein–Taybi, Soto and Turner syndromes and in association with trisomy 9, gliomatosis cerebri and glioblastoma.98,101,103–105

Etiology and pathogenesis.

The tumor derives from cells in the hair matrix. Mutations in the β-catenin gene, a gene associated with colon cancer, have been demonstrated in pilomatricomas.106 Mutations in APC causative for Gardner syndrome/FAP may result in pilomatricoma formation possibly by affecting a different part of the same Wnt signaling pathway.101

Diagnosis.

The histopathology of pilomatricoma is very characteristic, with two distinct types of cell, basophilic and shadow cells, located in the dermis or subcutis and surrounded by a fibrous capsule. The basophilic cells are seen at the periphery of the tumor and have rounded, darkly staining nuclei and scanty cytoplasm. The shadow cells are eosinophilic with a well-defined border and a central unstained area where the nucleus has been lost. Areas of keratinization may be seen, with foreign body giant cells and melanin pigmentation. Dystrophic calcification is a common finding and ossification occasionally occurs. Immunohistochemical staining typically shows nuclear β-catenin accumulation in the basaloid cellular component.101

Differential diagnosis.

The clinical differential diagnosis includes other skin tumors, dermoid cyst, or a calcified nodule. Dermoid cysts are attached to underlying tissues rather than to the skin. A calcified nodule is hard to palpation and has a white surface discoloration; it can be difficult to distinguish clinically from a calcified pilomatricoma. Ultrasound examination of pilomatricomas shows a mass with an echogenic center and a hyperechoic rim at the junction of the dermis and subcutaneous fat.107

Presentation with multiple lesions or familial disease should raise the possibility of an underlying genetic disorder.101

Treatment and prognosis.

Surgical excision with narrow margins or through a small skin incision is the treatment of choice. In asymptomatic lesions without progressive growth or recurrent inflammation, this may be deferred until the child is older and able to cooperate with excision under local anesthesia. Very superficial lesions may be amenable to incision and curettage. Spontaneous resolution is occasionally observed.

Granuloma annulare

Granuloma annulare is a benign inflammatory skin disorder of unknown etiology. The typical morphology is of skin-colored, erythematous or violaceous dermal papules that extend with centrifugal clearing to form an annular lesion with a beaded margin. Other variants include: subcutaneous granuloma annulare (Fig. 26.20), which may resemble rheumatoid nodules; a generalized papular form, perforating granuloma annulare; and a patch type.108

While not uncommon in school-aged children, granuloma annulare is rarely seen in infancy. A number of cases of generalized granuloma annulare have been reported in Korean children as young as 3 months of age.109,110 Two of these occurred following Bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccination.109 Subcutaneous granuloma annulare may occur in young children, and a case of apparent congenital onset has been described.111,112 Granuloma annulare with a rare linear distribution developed in an infant at 8 months of age.113 Unusual presentations of granuloma annulare are confirmed by the histopathologic finding of palisading granulomas associated with areas of collagen degeneration and mucin deposition in the dermis.

Most cases resolve spontaneously and treatment is rarely necessary.

Hamartomas

A hamartoma is a developmental abnormality of the skin in which there is an excess of one or more mature or nearly mature tissue structures normally found at that site.114 The term nevus is often used synonymously, although not all ‘nevi’ are hamartomas (e.g., nevus anemicus, nevus depigmentosus). Whether a lesion is designated a hamartoma or a nevus depends largely on tradition. An organoid nevus or organoid hamartoma refers to a malformation that contains adnexal structures such as sebaceous glands or hair follicles.115

Most hamartomas are isolated, sporadic malformations. They can be single or multiple, localized or extensive, and may be distributed in a linear or whorled pattern corresponding to the lines of Blaschko. Some arise from a post-zygotic mutation in the embryo that leads to somatic mosaicism.116 Others are manifestations of well-defined genetic disorders such as tuberous sclerosis. Epidermal hamartomas may be associated with underlying abnormalities in the central nervous system, skeleton, or other organs. Rarely, a post-zygotic mutation that involves the germline results in transmission of generalized skin disease to subsequent offspring.116,117

Epidermal nevus

The term epidermal nevus is used to encompass a group of hamartomas of ectodermal origin in which there is clinical and histopathologic overlap (Box 26.2). These include the nevus sebaceus, linear keratinocytic epidermal nevus, inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN), and nevus comedonicus. Other hamartomas that may be considered epidermal nevi are syringocystadenoma papilliferum, linear porokeratosis, Becker nevus, and the porokeratotic eccrine nevus (porokeratotic eccrine and ostial dermal duct nevus). Epidermal nevi also occur as a component of a number of well-defined or less well-defined syndromes.115,118 When applied without qualification, the term epidermal nevus usually refers to a keratinocytic epidermal nevus. Epidermal nevi affect about 0.1–0.3% of newborns.119

Nevus sebaceus

The nevus sebaceus (of Jadassohn) is an organoid hamartoma of appendageal structures and is present at birth. It occurs mainly where pilosebaceous and apocrine structures are prominent on the head and neck. There is no racial or gender predilection.

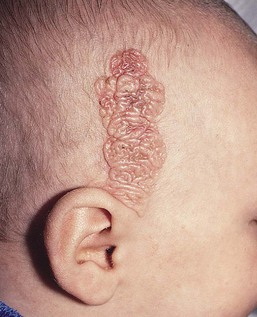

Cutaneous findings.

The typical nevus sebaceus is a pink-yellow or yellow-orange plaque with a pebbly or velvety surface that is located on the scalp or face (Fig. 26.21). It varies in size from one to several centimeters and can be round, oval, or linear in shape. Lesions on the scalp present as a congenital area of circumscribed alopecia (Fig. 26.21B). There may be evolution from a slightly raised plaque at birth to a flat, almost macular lesion in infancy and childhood. A verrucous or cobblestone appearance develops in adolescence when the sebaceous and apocrine glands enlarge and proliferate.114 Some lesions present with an atypical cerebriform (Fig. 26.22) or papillomatous morphology (Fig. 26.23![]() ).

).

Extracutaneous findings.

Nevus sebaceus is usually an isolated lesion with no extracutaneous findings. Rarely, it is associated with other developmental abnormalities in the Schimmelpenning or linear nevus sebaceus syndrome.115 The nevus sebaceus can be of any size or shape but is often extensive and/or linear, with a distribution following the lines of Blaschko. Extracutaneous manifestations include mental retardation, seizures and other central nervous system abnormalities, skeletal developmental anomalies, and ocular lesions, including coloboma of the eyelid and lipodermoid of the conjunctiva.115,117,120–122 Vitamin D-resistant hypophosphatemic rickets is a less common but well-described association.115,117,123,124 Vascular anomalies are also reported.125

A related syndrome in which an extensive nevus sebaceus is associated with a large speckled lentiginous nevus (which appears as an area of segmental hyperpigmentation in infancy) is termed phakomatosis pigmentokeratotica (PPK) (see Chapter 24). Hypophosphatemic rickets occurs more commonly in PPK whereas ocular lipodermoids and colobomas are apparently not found.115 Nevus sebaceus adjacent to an area of aplasia cutis congenita has been termed didymosis aplasticosebacea, or SCALP syndrome when the additional features of CNS abnormalities, limbal dermoid and pigmented melanocytic nevus are present.126

Etiology and pathogenesis.

Nevus sebaceus is thought to be caused by a post-zygotic somatic gene mutation. Lesional mutations in HRAS, and less commonly KRAS, have been identified both in localized nevus sebaceus and in Schimmelpenning syndrome.119,127 There have been rare reports of familial occurrence of nevus sebaceus.128,129 The Schimmelpenning syndrome occurs sporadically, and an autosomal lethal mutation that survives by mosaicism is postulated.130

Diagnosis.

The diagnosis of nevus sebaceus is usually made on clinical grounds except in atypical cases. In infancy and childhood the characteristic histopathologic changes are less developed than in adolescence and adulthood. Mature lesions show numerous hyperplastic sebaceous and apocrine glands in the dermis, with overlying epidermal hyperplasia. In infants the histopathologic findings are more subtle, with rudimentary hair follicles and immature glandular structures. Sebaceous hyperplasia may not be so evident in a linear nevus sebaceus localized outside the head and neck area.115

Differential diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis of a circumscribed area of alopecia on the scalp at birth includes aplasia cutis congenita and neural tube closure defects such as meningocele, encephalocele, and rests of heterotopic meningeal or brain tissue in the skin (see Chapter 9). Aplasia cutis congenita can be distinguished by the presence of atrophy and scarring, and in some cases ulceration of the skin at birth. Neural tube defects are located in or close to the midline at the vertex, nasal bridge, or lower occipital scalp. Both aplasia cutis congenita and neural tube closure defects may show a collarette of dark terminal hair in the newborn.131 Eczematous changes overlying a nevus sebaceus may sometimes cause diagnostic confusion.132

Treatment and prognosis.

The nevus sebaceus has a propensity to develop neoplastic growths, most of which are benign appendageal tumors such as syringocystadenoma papilliferum, trichilemmoma, trichoblastoma, and apocrine cystadenoma. Malignant tumors include basal cell epithelioma, squamous cell carcinoma, and apocrine or sebaceous carcinoma. These tumors are unusual in childhood, are localized to the skin lesion and rarely metastasize, although they may be locally invasive.133 The lifetime risk of developing a superimposed malignant tumor is uncertain, and previously high figures may be due to ascertainment bias.133 More recent studies have found a lower incidence of malignant tumors and suggest that benign follicular neoplasms such as trichoblastoma may have been misinterpreted as basal cell carcinoma in the past.134–136 Changes that should lead one to suspect a neoplastic growth include surface ulceration or the development of a nodule within the lesion.

The need for prophylactic excision of a nevus sebaceus is controversial.134–136 Decisions regarding surgery should be individualized. Excision may be performed in infancy or postponed until later childhood or adolescence. Continued observation may be preferable to surgery for lesions that are difficult to excise with a good cosmetic result, particularly on the face.

Syringocystadenoma papilliferum

Syringocystadenoma papilliferum (SCAP) is a benign adnexal hamartoma believed to be derived from either apocrine and/or eccrine glands or pluripotential appendageal cells.137 When it occurs de novo, it is typically congenital but some cases develop later in life. The clinical appearance is of one or more papules or papillomatous lesions arranged singly or in clusters, as a confluent plaque, or in a linear distribution. Papules may be skin colored, pink or light brown and there may be surface ulceration.138 The scalp, face, and neck are the typical sites of predilection. However, lesions occur on the trunk and extremities in approximately 25% of cases and unusual presentations are described.139 Development of SCAP in an 8-year-old child with focal dermal hypoplasia and a documented PORCN mutation is reported.140

Syringocystadenoma papilliferum arises within a nevus sebaceus in at least 30% of cases.139 It may also rarely be associated with other adnexal hamartomas such as apocrine cystadenoma, hidrocystoma and apocrine nevus. The diagnosis is made by histopathologic examination. This is characterized by cystic and epidermal invaginations with papillary projections lined by an outer layer of cuboidal cells and an inner layer of columnar cells; a connective tissue core contains plasma cells and lymphocytes.

Surgical excision is the treatment of choice. Ablation with the CO2 laser has been described in a newborn.141 There are rare reports of syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum arising from SCAP in older adults.142

Keratinocytic epidermal nevus

The keratinocytic epidermal nevus is a nonorganoid hamartoma of keratinocytes that may present at birth, within the first few years of life, or sometimes later.117 There are a number of histopathologic variants including nonepidermolytic, epidermolytic and inflammatory linear epidermal nevus subtypes.117

Cutaneous findings.

The keratinocytic epidermal nevus presents at birth or during early childhood and may continue to extend for a variable period.117 Rarely, new lesions become apparent in adolescence or adult life. They vary in extent from a small cluster or linear arrangement of pigmented, warty papules to widespread linear and swirled areas of pigmentation following the lines of Blaschko (Fig. 26.24A,B). A linear keratinocytic nevus may involve an entire limb, half of the body in a unilateral distribution, or both sides of the trunk, limbs, and face in a symmetric pattern, with demarcation at the midline. Extensive bilateral lesions have been referred to historically as ‘systematized epidermal nevus’ or ‘ichthyosis hystrix,’ and unilateral lesions as ‘nevus unius lateris.’

Keratinocytic nevi may have a macerated appearance at birth because of prolonged contact with amniotic fluid (Fig. 26.24C). During childhood, the degree of verrucosity varies from subtle, almost flat pigmentation to a grossly elevated, warty appearance.117 They have a tendency to become more verrucous with age, particularly during puberty. Keratinocytic nevi involving the head and neck often exhibit the morphology of a nevus sebaceus. Scalp lesions may be associated with woolly hair nevus, and occasional epidermal nevi have overlying hypertrichosis.143 A linear lesion that impinges on the nail matrix may cause dystrophy of the involved nail.

A number of patients with one or more small hyperkeratotic papules with a distinctive histopathologic appearance have been described as ‘papular epidermal nevus with skyline basal cell layer’ or PENS.144 Somewhat similar epidermal nevi with a white color have been observed at birth as a presentation of tuberous sclerosis.145

The linear inflammatory verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN) is an extremely pruritic, erythematous lesion that can occur at any site, but is most often seen on the limbs or perineum in girls (Fig. 26.25). It may simulate linear psoriasis or linear lichen planus. It is rarely present at birth, but may appear in the first months of life.

Extracutaneous findings.

Most keratinocytic nevi are isolated lesions with no evidence of extracutaneous disease. A number of syndromes are associated with non-epidermolytic keratinocytic nevi.115,118 These include Proteus syndrome; CLOVES (congenital lipomatous overgrowth, vascular malformation, epidermal nevus and skeletal abnormalities) syndrome; type 2 segmental Cowden disease; FGFR3 epidermal nevus, and CHILD (congenital hemidysplasia with ichthyosiform nevus and limb defects) syndrome.115,118 In the Proteus syndrome, epidermal nevi occur in association with limb overgrowth, lipomatous lesions, cerebriform malformations of the feet, and cutaneous vascular anomalies.106,117 The CHILD syndrome is characterized by verrucous lesions corresponding to the lines of Blaschko in conjunction with limb reduction defects.117,130

Extracutaneous manifestations have also been described in association with PENS.146,147

Diagnosis.

The most common histopathologic pattern is that of a benign papilloma, with acanthosis, elongation of rete ridges, hyperkeratosis, and papillomatosis. This histopathologic appearance may be shared by viral warts, seborrheic keratosis, or acanthosis nigricans. Histopathology of lesions from the scalp may reveal features of a nevus sebaceus, especially after puberty. A subset of keratinocytic nevi shows the histopathologic features of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, characterized by perinuclear vacuolization of keratinocytes and increased numbers of enlarged keratohyalin granules with overlying hyperkeratosis. In a less common variant, there is acantholytic hyperkeratosis similar to that seen in Darier disease.148 Another rare variant is linear Cowden nevus, described as having a soft, thick papillomatous appearance and associated with a PTEN mutation.115 In PENS, the basal cell nuclei have a characteristic palisaded pattern.144 Histopathologic findings in ILVEN include psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia and an inflammatory infiltrate in the upper dermis.117 The nevus of CHILD syndrome resembles ILVEN but may also have collections of foam cells in the upper dermis consistent with a verruciform xanthoma.117

Etiology and pathogenesis.

The distribution of lesions following the lines of Blaschko suggests somatic mosaicism. Chromosomal mosaicism has been demonstrated in a number of patients with linear keratinocytic nevi.149,150 Keratin 1 and 10 gene mutations have been identified in epidermolytic keratinocytic nevi.151 Keratinocytic nevi are thought to represent a phenotypic expression of several genetic defects due to post-zygotic mutations, rather than a single disease. Whether the basic pathogenetic defect of nonepidermolytic lesions lies in the dermal fibroblast or in the keratinocyte is not known.

Differential diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis of a localized cluster of lesions includes viral warts, which do not commonly have a linear arrangement and regress spontaneously with time. Linear lesions at birth may be confused with the verrucous stage of incontinentia pigmenti. Linear keratinocytic nevi that develop during infancy and childhood differ in morphology, if not in distribution, from lichen striatus, a self-limiting disorder with an inflammatory, papular appearance and lichenoid histopathology. The differential diagnosis of ILVEN includes lichen simplex chronicus, linear psoriasis, and linear lichen planus, none of which is seen in the newborn period.

The CHILD syndrome, the CLOVE syndrome and Proteus syndrome have distinctive clinical features.

Treatment and prognosis.

Unlike nevus sebaceus, the linear keratinocytic nevus is rarely associated with the development of superimposed benign or malignant tumors in adult life. Patients with epidermal nevi should be evaluated clinically for manifestations of one of the epidermal nevus syndromes.115,118 When histopathologic examination shows epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, the patient should receive counseling about the potential for genetic transmission of a keratinopathic ichthyosis via germline mutation although the actual risk of transmission is not known.

Treatment may be requested for cosmetically disfiguring lesions but is generally undertaken in later childhood or adolescence. Excision of small lesions or localized areas of larger lesions may be feasible. Treatment of extensive nevi is difficult. Various destructive modalities, including CO2 laser ablation, dermabrasion, or liquid nitrogen cryotherapy, have been attempted, but there may be recurrence.117 The same is true for pharmacologic treatments such as topical or oral retinoids and 5-fluorouracil.152

Nevus comedonicus

A nevus comedonicus is a developmental abnormality of the pilosebaceous unit that appears as a grouped or linear arrangement of small or large comedones. Lesions present at birth or during infancy in the majority of cases. Nevus comedonicus is considered a rare type of epidermal nevus.

Cutaneous findings.

Groups of enlarged follicular openings containing pigmented, comedo-like keratin plugs may be localized or extensive (Fig 26.26). Most nevi are unilateral and located on the face or upper trunk. They frequently have a linear arrangement. Extensive lesions are distributed along the lines of Blaschko and are limited at the midline.153,144 There may be associated white papules representing milia, closed comedones, or deeper follicular cystic structures. Interfollicular atrophy is often observed.115

Later in childhood or adolescence these lesions may develop painful, inflammatory cystic nodules and acneiform scarring (Fig. 26.26).154 The coexistence of a nevus comedonicus and a keratinocytic epidermal nevus has been reported.155 Comedo-like structures may also be seen within keratinocytic nevi.117

Extracutaneous findings.

In most cases, there are no extracutaneous manifestations. Rarely, a nevus comedonicus is associated with ipsilateral central nervous system, skeletal, and ocular abnormalities in the nevus comedonicus syndrome.115 Ipsilateral cataracts are a characteristic feature.115 Rarely, these extracutaneous anomalies may be localized contralaterally.115

Etiology and pathogenesis.

Nevus comedonicus is a sporadic disorder and is not inherited. The pathogenesis is believed to involve somatic mosaicism.130,156 A mutation in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) gene detected in an inflammatory acne nevus suggests that some cases of this type of nevus represent a mosaic form of Apert syndrome.157

Diagnosis.

The diagnosis is made on the clinical appearance of the lesion. Histopathologic examination reveals hyperkeratosis and acanthosis of the epidermis with widely dilated, keratin-filled, cystic structures. Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis may be observed in the keratinocytes of the follicular epithelial wall.153,154

Differential diagnosis.

The localized appearance of the lesion is very characteristic and unlikely to be mistaken for comedonal acne unless bilateral.156

Porokeratotic eccrine nevus presents with comedo-like lesions on the palms and soles and has distinctive histopathologic features.

Inflammatory cysts may closely resemble cystic acne.

Nevus comedonicus syndrome should be distinguished from the Happle–Tinschert syndrome, in which multiple segmentally arranged basaloid follicular hamartomas are associated with ipsilateral osseous, dental and cerebral anomalies, and from a less well-defined syndrome with multiple trichilemmal cysts arranged along Blaschko’s lines.115,118,158

Treatment and prognosis.

Recurrent inflammation and scarring can cause cosmetic disfigurement. Treatment is difficult. Excision of smaller lesions is curative,159 but inflammatory acneiform cysts may recur if excision is incomplete. Pharmacologic agents such as oral or topical retinoids are of minimal benefit. Topical and systemic antibiotics have been used to treat inflammatory lesions, with variable success.156

Porokeratotic eccrine nevus

The porokeratotic eccrine nevus is a congenital hamartoma of the eccrine ducts and follicular openings. Although usually present at birth, lesions may first appear in later childhood or adult life. Other terms used to describe this hamartoma include porokeratotic eccrine ostial and dermal duct nevus, porokeratotic eccrine and hair follicle nevus and porokeratotic adnexal ostial nevus.160

Cutaneous and extracutaneous findings.

Porokeratotic eccrine nevus is characterized clinically by grouped comedo-like keratotic papules or pits on a palm or sole.161 Lesions may be more widespread with a linear distribution following the lines of Blaschko.162 Keratotic papules and plaques located in sites other than the palms and soles may resemble a linear keratinocytic nevus or ILVEN.162,163 Multiple erosions and atrophy have been reported in cases presenting in the newborn period.160 Most cases are asymptomatic but pruritus has been reported.160 Rare cases have associated anhidrosis, hair loss and nail dysplasia, psoriasis, palmar plantar keratoderma or ipsilateral breast hypoplasia.160 Development of Bowen disease or squamous cell carcinoma within the lesional skin is an unusual complication.160

Cases of generalized porokeratotic eccrine nevus associated with deafness and also with the keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness (KID) syndrome have been reported.164–166

Etiology and pathogenesis.

The pathogenesis is believed to represent a circumscribed disorder of keratinization localized to the acrosyringium and follicular ostia.162 Somatic mutations in the GJB2 gene encoding the gap junction protein connexin 26, have been identified in patients with generalized porokeratotic eccrine nevus suggesting it might be a mosaic form of the KID syndrome.166 These authors also report the observation of generalized lethal KID syndrome in an infant born to a mother with porokeratotic eccrine nevus.

Diagnosis.

Histopathologically, there are epidermal invaginations with parakeratotic plugs emerging from dilated eccrine ostia and follicular openings, surrounded by parakeratotic columns of cornoid lamellae.160

Differential diagnosis.

The clinical differential diagnosis includes linear porokeratosis, nevus comedonicus, and linear keratinocytic nevus. Histopathologically, punctate porokeratosis and linear porokeratosis of Mibelli can be distinguished by the lack of epidermal invaginations. The histopathologic features can resemble those seen in KID syndrome.166

Congenital smooth muscle hamartoma

Congenital smooth muscle hamartoma is a benign cutaneous developmental anomaly characterized by an excess of arrector pili muscle within the reticular dermis. It is usually evident at birth or shortly thereafter. The estimated prevalence is 1 in 2600 live births, with a slight male preponderance.168 Rarely, more extensive involvement may be associated with the phenotype of the ‘Michelin tire baby’.169–172

Cutaneous findings.