10 Lower Extremity Block Anatomy

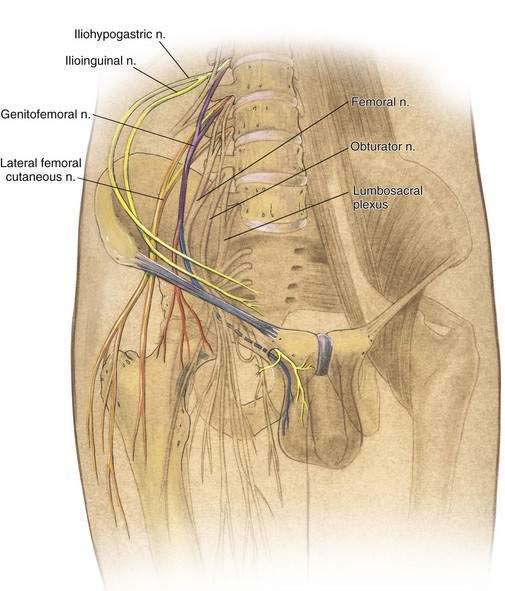

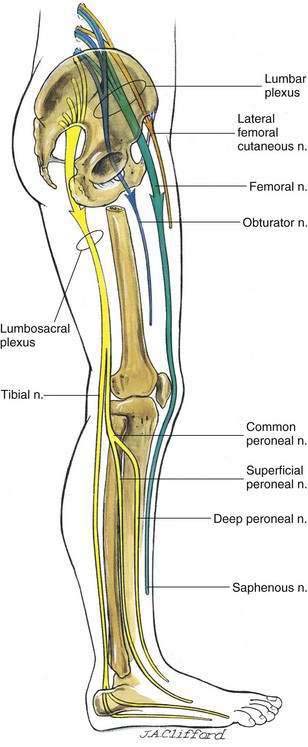

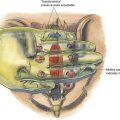

Anesthesiologists are more comfortable carrying out lower extremity regional block than upper extremity regional block because of the ease and simplicity of blocking the lower extremities with neuraxial techniques. Also, in no anatomic site outside the neuraxis are the lower extremity plexuses as compactly packaged as are the nerves to the upper extremity in the brachial plexus. If one compares the path of lower extremity nerves over the pelvic brim to the path of the brachial plexus over the first rib, it is clear that the four major nerves to the lower extremity exit from four widely differing sites (Figs 10-1 and 10-2). Thus, regional block of the lower extremity focuses on block of individual peripheral nerves, and my approach to anatomy will follow that concept.

Two major nerve plexuses innervate the lower extremity: the lumbar plexus and the lumbosacral plexus. The lumbar plexus primarily innervates the ventral aspect, whereas the lumbosacral plexus primarily innervates the dorsal aspect of the lower extremity (see Fig. 10-2).

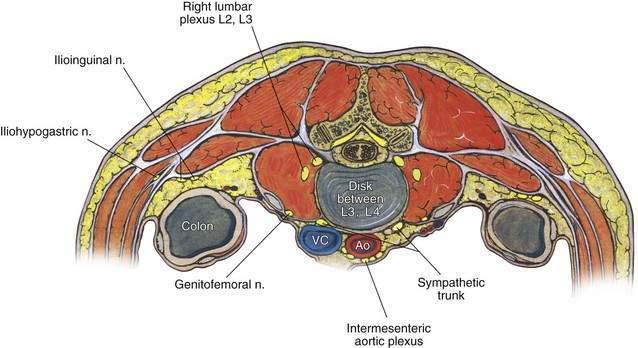

The lumbar plexus is formed from the ventral rami of the first three lumbar nerves and part of the fourth lumbar nerve. In approximately half of patients, a small branch from the twelfth thoracic nerve joins the first lumbar nerve. The lumbar plexus forms from the ventral rami of these nerves anterior to the transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae deeply within the psoas muscle (Fig. 10-3). The cephalad portion of the lumbar plexus (i.e., the first lumbar nerve, and often a portion of the twelfth thoracic nerve) splits into superior and inferior branches. The superior branch redivides into the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves, and the smaller inferior branch unites with a small superior branch of the second lumbar nerve to form the genitofemoral nerve (see Fig. 10-1).

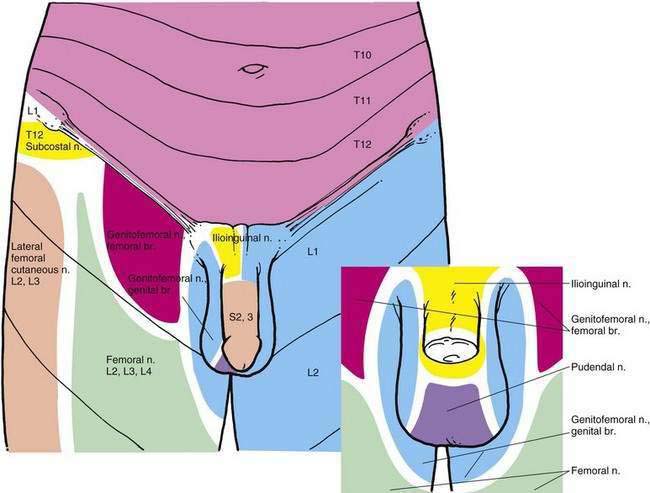

The iliohypogastric nerve penetrates the transversus abdominis muscle near the crest of the ilium and supplies motor fibers to the abdominal musculature. It ends in an anterior cutaneous branch to the skin of the suprapubic region and a lateral cutaneous branch in the hip region (Fig. 10-4).

The ilioinguinal nerve courses slightly inferior to the iliohypogastric nerve. It then traverses the inguinal canal and ends cutaneously in branches to the upper and medial parts of the thigh and near the anterior scrotal nerves, which supply the skin at the root of the penis and the anterior part of the scrotum in males (see Fig. 10-4). In females, the comparable anterior labial nerves supply the skin of the mons pubis and labia majora.

The genitofemoral nerve divides at a variable level into genital and femoral branches. The genital branch is small; it enters the inguinal canal at the deep inguinal ring and supplies the cremaster muscle, small branches to the skin and fascia of the scrotum, and adjacent parts of the thigh. The femoral branch is the more medial of the two branches and continues under the inguinal ligament on the anterior surface of the external iliac artery. Below the inguinal ligament, it pierces the femoral sheath and passes through the saphenous opening to supply the skin over the femoral triangle lateral to that supplied by the ilioinguinal nerve (see Fig. 10-4). These three nerves are clinically important during regional block for inguinal herniorrhaphy or other groin procedures carried out under regional block.

Caudal to these three nerves are three major nerves of the lumbar plexus that exit from the pelvis anteriorly and innervate the lower extremity. These are the lateral femoral cutaneous, femoral, and obturator nerves (see Figs. 10-1 and 10-2).

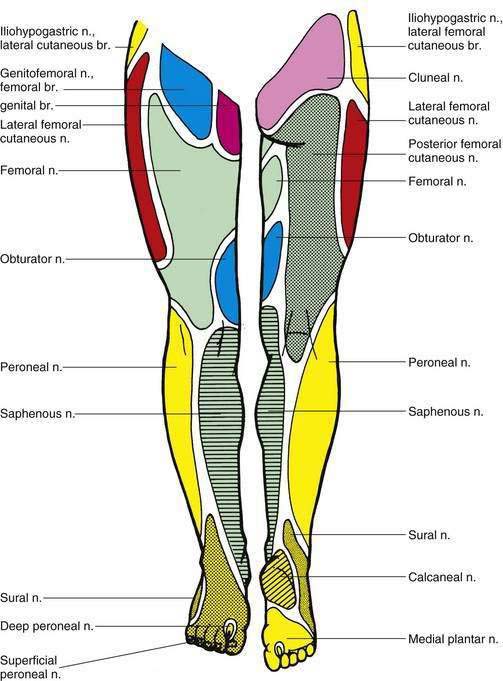

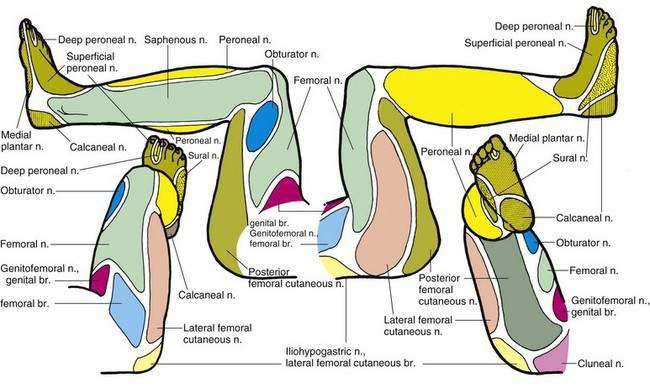

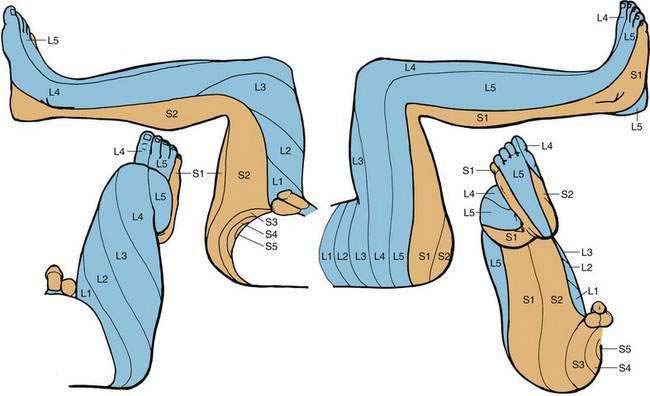

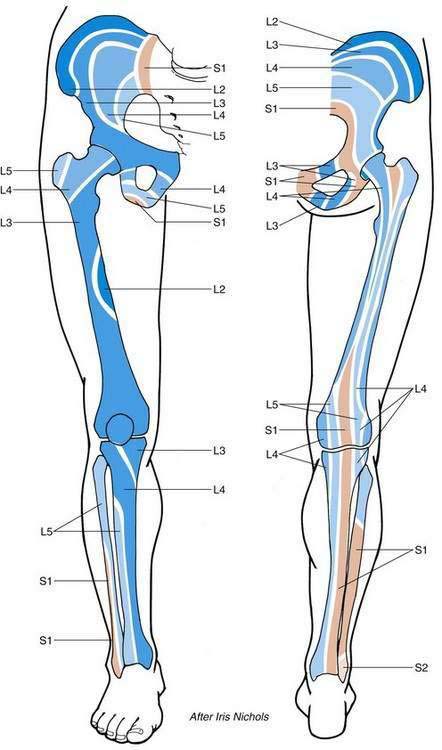

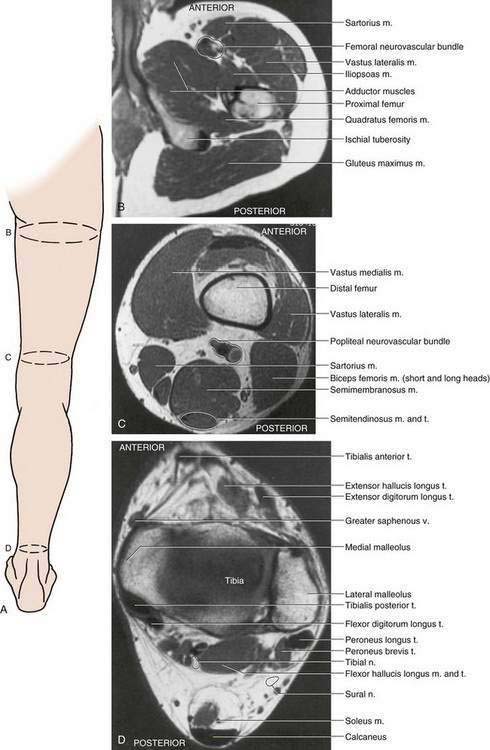

Figures 10-5 and 10-6 illustrate the cutaneous innervation of the peripheral nerves of the lower extremity. This subject is illustrated with the patient’s lower extremity in both the anatomic and the lithotomy positions for greatest clinical utility. Figure 10-7 illustrates the dermatomal innervation of the lower extremities in a similar manner. Figure 10-8 illustrates the osteotome pattern of lower extremity innervation and will be most useful to anesthesiologists who are providing anesthesia for orthopedic procedures. Figure 10-9 helps clarify the cross-sectional anatomy pertinent to regional block of the lower extremity.