CHAPTER 68 LOWER EXTREMITY AND DEGLOVING INJURY

Injuries of the lower extremity can be devastating (see Mangled Extremities section) and life-threatening or minimal and quickly healed. Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) assessments should be made on all patients. The history, if obtainable, should include the mechanism of injury, initial physical examination by emergency medical services, and any pertinent medical information. Control of exsanguinating hemorrhage and splint immobilization should take priority.

OPEN FRACTURES

Identification and Classification

Open fractures require special attention to minimize risk of clostridial and pyogenic infections. Treatment is guided by classification of the severity of the injury, primarily according to the extent of soft tissue trauma, and level of contamination (Table 1). It is important to consider the entire soft tissue wound and not just the skin opening. In severe crush injuries, small lacerations may overlie extensively contused or necrotic soft tissue.

| Grade I | Small wounds caused by low-velocity trauma, with minimal contamination and soft tissue damage (e.g., skin laceration by bone end or a low-velocity gunshot wound). |

| Grade II | Wounds more extensive in length and width, but that have little or no avascular or devitalized soft tissue and minimal contamination. |

| Grade IIIA | Significant wounds caused by high-energy trauma, often with extensive lacerations and soft tissue flaps, but such that after final debridement, adequate local soft tissue coverage is maintained and delayed primary closure is feasible. |

| Grade IIIB | Major wounds with considerable devitalized soft tissue, contamination, or both. Bone is exposed in the wound, and extensive periosteal avulsion may be present. Coverage of the soft tissue defect usually requires a local or free microvascular muscle pedicle graft. |

| Grade IIIC | Open fracture with an associated arterial injury that requires repair. |

Management

Wound Coverage

For all but the most trivial wounds and especially when open fractures are internally fixed, it is best to avoid primary wound closure. When wounds are left open, the use of antibiotic bead-pouch dressing technique developed by Seligson and colleagues20 is still a good technique. Polymethylmethacrylate cement (one full sized batch) is mixed with 1.2 g of tobramycin powder. This is used to make beads of 5-mm diameter, which are molded onto twisted stainless steel wire, separated by 3–4 mm. Although this can be done by the surgical team in the OR, our pharmacy follows the procedures described by Seligson and colleagues20 for prefabrication and gas sterilization of bead chains, which are made available to us in individual sterile peel-apart pouches. The beads are placed in the wound, and a large piece of Tegaderm or Opsite is used to cover and seal the opening and to keep the gentle traction of the wound flaps to prevent flap shrinkage.

COMPARTMENT SYNDROMES

Forearm compartment syndromes may involve anterior (flexor) or posterior (extensor) muscles and may require releasing the intrinsic fascia of each involved muscle. An extensive surgical approach is required, such as McConnell’s combined exposure of the median and ulnar nerves, as described by Henry in Extensile Exposure.1

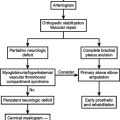

MANGLED EXTREMITIES: DELAYED AMPUTATION

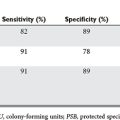

Many scoring systems have been developed to predict those patients who should undergo immediate amputation and those who should have reconstruction. Our own bias is reflected by Bonanni et al.,13 who state that predictive scoring is an exercise in futility. In their study, they could not show reliable sensitivity or specificity using the MESI, PSI, MESS, or the LSI. Surgical judgment based on experience is still the gold standard.

In a recent study by Bosse et al.,17 of 569 patients with severe leg injuries who underwent reconstruction or amputation, the sickness impact profile (SIP) showed no difference in outcomes between these two groups. Their study did show that there was a poorer score for the SIP if the patient was rehospitalized or had a major complication, lower educational level, nonwhite ethnicity/race, poverty, lack of private health insurance, poor social support network, low selfefficiency, smoking, and involvement in disability-compensation litigation. Interestingly, patients who underwent reconstruction were more likely to be rehospitalized than those who underwent amputation. Return to work in the two groups was similar. The fact that the groups are similar reflects good decisions made by the surgeons.

Few other areas in trauma care are as controversial as whether amputations for mangled extremities should be done early or delayed. The most common reasons for delayed amputation are loss of wound cover in un-united fractures, infection in a nonunion fracture, an insensate limb, recurrent ulcerwations, a dystrophic limb, sympathetic dystrophy, and phantom pain, to name a few. Some surgeons have argued that functional recovery is faster and less costly following amputation than with multiple procedures for salvage and reconstruction. In addition to the study by Bosse et al.17 mentioned previously, Pozo et al.18 studied 35 patients who had amputation following the failure of treatment for severe lower limb trauma. Seven of the amputations were for ischemia within 1 month of the injury; 13 were between 1 month and 1 year for infection, complicating loss of limb cover or un-united fractures; and 15 occurred later than 1 year postinjury mainly for infected nonunion. The latter group had an average of 12 operations and 50 months of treatments, including 8 months in hospital. Factors that contributed to salvage failure were vascular injuries, nerve damage, bone damage, muscle damage, skin cover, and sepsis. Overall, these authors concluded that if lower limb reconstruction is attempted, it should be assessed very early on by two specialists, one in trauma surgery and the other in orthopedic or plastic surgery, as to whether failure is inevitable. Obviously, this requires experience, and persistent attempts at salvage can be extremely difficult.

Another study that might influence surgeons on whether to salvage comes from Case Western Reserve.16 Thirty-four patients were followed, of whom 16 had a successful limb salvage procedure, and 18 had an immediate below knee amputation (BKA). The patients who had a successful limb salvage procedure took significantly more time to achieve full weight bearing, were less willing or able to work, and had higher hospital charges than the patients who had been managed with an early BKA. Furthermore, patients who had limb salvage considered themselves severely disabled, and they had more problems than the amputation group with the performance of occupational and recreational activities. These quality-of-life evaluations, however, must be put into the perspective that Bosse and MacKenzie17 have already outlined.

In a final study for consideration, Roessler and colleagues19 reviewed 80 patients for a 4-year period and asked the question of when to amputate. They concluded that neurologic, bone, and tissue status influenced the decision regarding immediate amputation, but had little to do with delayed loss of limb or life. Somewhat surprisingly, they found that the circulation as determined by the presence or absence of a palpable or Doppler-detected pulse was critical. They concluded that in cases in which salvage is attempted, amputation should be performed at 24 hours if the patient’s condition, including a markedly positive fluid balance, indicates systemic compromise. They also made the observation that in the absence of a distal pulse on presentation, the eventual amputation rate is high.

1 Henry AK. Extensile Exposure, 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1973.

2 Mackinnon SE, Dellon AL. Surgery of the Peripheral Nerve. New York: Thieme, 1988.

3 McCraw JB, Arnold PC. McCraw and Arnold’s Atlas of Muscle and Musculocutaneous Flaps. Norfolk: Hampton Press, 1986.

4 Serafin D. Atlas of Microsurgical Composite Tissue Transplantation. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1996.

5 Caudle RJ, Stern PF. Severe open fractures of the tibia. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1987;69:801-807.

6 Hansen STJr. The type-IIIC tibial fracture: salvage or amputation. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1987;69:799-800.

7 Dagum AB, Best AK, Schemitsch EH, et al. Salvage after severe lower-extremity trauma: are the outcomes worth the means? Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:1212-1220.

8 Eairhurst MJ. The function of below-knee amputee versus the patient with salvaged grade III tibial fracture. Clin Orthop. 1994;301:227-232.

9 Gustilo RB, Mendoza RM, Williams DN. Problems in the management of type III (severe) open fractures: a new classification of type III open fractures. J Trauma. 1984;24:742-746.

10 Swiontkowski MF, MacKenzie FJ, Bosse MJ, et al. Factors influencing the decision to amputate or reconstruct after high-energy lower extremity trauma. J Trauma. 2002;52:641-649.

11 Johansen K, Daines M, Howey T, et al: Objective criteria accurately predict amputation following lower extremity trauma. J Trauma 30:568–573.

12 Matsen SL, Malchow D, Matsen FAIII. Correlations with patients’ perspectives of the result of lower-extremity amputation. J Bone joint Surg [Am]. 2000;82:1089-1095.

13 Bonanni F, Rhodes M, Lucke JF. The futility, of predictive scoring of mangled lower extremities. J Trauma. 1993;34:99-104.

14 Bondurant FJ, Cotler HB, Buckle R, et al. The medical and economic impact of severely injured lower extremities. J Trauma. 1988;23:1270-1273.

15 Butcher JL, MacKenzie EJ, Cushing B, et al. Long-term outcomes after lower extremity trauma. J Trauma. 1996;41:4-9.

16 Georgiadis GM, Behrens FF, Joyce MJ, et al. Open tibial plateau fractures with severe soft-tissue loss. Limb salvage compared with below-the-knee amputation. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1993;75A:1431-1442.

17 MacKenzie EJ, Burgess AR, McAndrew MP, et al. Patient oriented functional outcome after unilateral lower extremity fracture. J Orthop Trauma. 1993;7:393-401.

18 Pozo JL, Powell B, Hutton PA N, Clarke J. The timing of amputation for lower limb trauma. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1990;728:288-292.

19 Roessler MS, Wisner DH, Holcroft JW. The mangled extremity: when to amputate? Arch Surg. 1991;126:1243-1249.

20 Henry SL, Ostermann PA, Seligson D. The antibiotic bead pouch technique: the management of severe compound fractures. Clin Orthop. 1993;295:54-62.