Chapter 30 Lower Back and Lower Limb Pain

Lower back pain is one of the most common reasons for neurological and neurosurgical consultation. The cost to society is huge, with estimates of up to $80 billion per year in direct and indirect healthcare costs and loss of productivity. In Switzerland, low back pain consumes 6.1% of the total healthcare budget and up to 2.3% of their GDP (Wieser et al., 2010). In many of the patients who present with lower back pain, the pain either developed or was exacerbated as a result of occupational activity. Lower limb pain is a common accompaniment to lower back pain but can occur independently.

Related Anatomy and Physiology

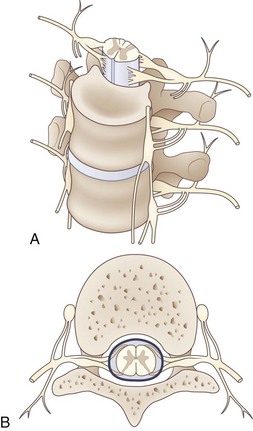

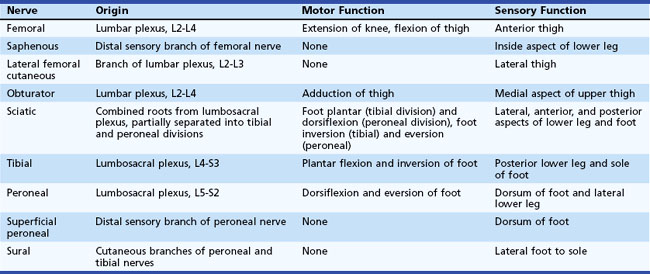

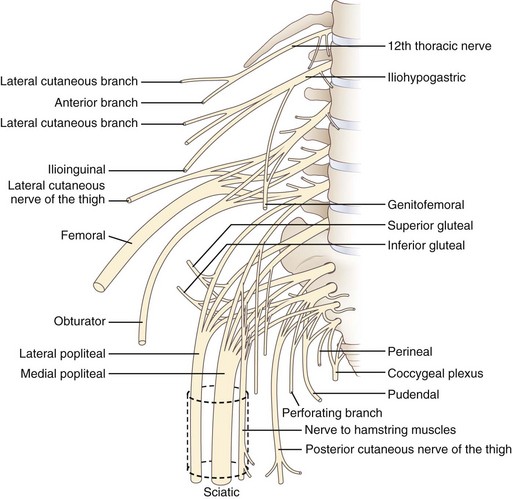

The lumbosacral spinal cord terminates in the conus medullaris at the level of the body of the L1 vertebra (Fig. 30.1). The motor and sensory nerve roots from the lumbosacral cord form the cauda equina. From there, the motor and sensory nerve roots unite at the dorsal root ganglion to form the individual spinal nerves. These anastomose in the lumbosacral plexus (Fig. 30.2), from which run the major nerves supplying the leg (Table 30.1).

Fig. 30.2 Anatomy of the lumbosacral plexus.

(Reprinted with permission from Bradley, W.G., 1974. Disorders of the Peripheral Nerves. Blackwell, Oxford, p. 29.)

Causes of lower back pain without leg pain include:

Causes of lower back plus lower limb pain include:

Important causes of leg pain without low back pain include:

Diagnosis

History and Examination

The history should focus first on features of the back and leg pain:

Associated motor and sensory symptoms

Associated motor and sensory symptoms

Exacerbating and remitting factors

Exacerbating and remitting factors

History of predisposing factors (e.g., trauma, cancer, osteoporosis)

History of predisposing factors (e.g., trauma, cancer, osteoporosis)

Differential Diagnosis of Lower Back and Leg Pain

The differential diagnosis of lower back and leg pain can be addressed as shown in Tables 30.2 through 30.5. Classification into mechanical and neuropathic categories is useful to narrow the scope of diagnostic considerations. The possibility of non-neurological causes should always be kept in mind.

| Type | Examples |

|---|---|

| Mechanical pain |

Table 30.3 Differential Diagnosis of Lower Back and Leg Pain

| Disorder | Clinical Features | Diagnostic Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Radiculopathy | Back pain radiating into leg in a dermatomal distribution. Sensory loss and motor loss are in a root distribution. Increased pain with coughing or straining. | Suspected when neuropathic pain radiates from back down into leg in a single root distribution. Disk or mass can be seen on MRI or CT. Zoster and diabetes can cause radiculopathy without abnormal studies. |

| Plexopathy | Back and leg pain with a neuropathic character, dysesthesias, burning, or electric sensation. Back pain can develop when cause is mass lesion in region of plexus. | Suspected when patient has leg pain in more than one peripheral nerve or root distribution. MRI of plexus or CT of abdomen and pelvis can show mass or hematoma. |

| Spinal stenosis | Pain in lower back, buttocks, and legs, especially with standing, walking, and lumbar spine extension. | MRI or CT shows obliteration of subarachnoid space. |

CT, Computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Table 30.4 Differential Diagnosis of Isolated Lower Back Pain

| Disorder | Clinical Features | Diagnostic Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Sacroiliac joint inflammation | Pain lateral to spine where sacrum inserts into top of iliac bone. Pain is exacerbated by movement and pressure but does not radiate down leg. | Clinical diagnosis. Radiographs can show degenerative changes in joint. Bone scan shows increased uptake in region. |

| Facet pain | Unilateral or bilateral paraspinal pain without radiation. Pain is increased by spine motion, especially extension. | Clinical diagnosis. Radiographs can show facet degeneration. |

| Ovarian cyst or cancer | Pain in hip and lower back, often but not always extending into lower quadrant. Bowel disturbance may develop with advanced disease. | Abdominal and pelvic CT shows mass lesion in ovary. |

| Endometriosis | Usually pelvic pain but occasionally pain in back and legs. Pain is often timed to menses. | Diagnosis suspected during pelvic exam. Vaginal ultrasound is supportive. Laparoscopy is diagnostic. |

| Retroperitoneal mass, abdominal aortic aneurysm, abscess, hematoma | Pain in back. May be bilateral to spine. May be associated with superimposed neuropathic pain in cases with plexus or proximal nerve involvement. | CT or MRI shows hematoma, aneurysm, eroding vertebral bodies, or abdominal mass. |

| Urolithiasis | Pain in upper to mid-back laterally that may radiate to groin. No radiation into leg. | Radiographs may show stones. Intravenous pyelography typically shows obstruction of flow. Contrasted abdominal CT usually shows the stone and obstruction. |

| Diskitis | Pain in lower back exacerbated by movement. Some patients may have radiation of pain to abdomen, hip, or leg. | MRI shows characteristic changes in disk and surrounding tissues. |

Table 30.5 Differential Diagnosis of Isolated Leg Pain

| Disorder | Clinical Features | Diagnostic Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Peroneal neuropathy | Loss of sensation on dorsum of foot. Weakness of foot and toe dorsiflexion. | Slowed nerve conduction velocity across region of entrapment, usually at fibular neck. EMG may show denervation in peroneal-innervated muscles, especially tibialis anterior, without involvement of short head of biceps femoris. |

| Femoral neuropathy | Pain and sensory loss in anterior thigh, often with weakness of quadriceps and suppression of knee reflex. | NCS can sometimes be performed but may be technically difficult. EMG may show denervation in a distribution limited to femoral nerve. |

| Piriformis syndrome | Pain from back or buttock down posterior thigh. Pain is exacerbated by sitting or climbing stairs. Stretch of piriformis (flexion and adduction of the hip) worsens pain. | Clinical diagnosis. Pain radiating down leg in a sciatic nerve distribution. Exacerbation of pain by flexion and adduction of hip. EMG and NCS may show proximal sciatic nerve damage. |

| Meralgia paresthetica (lateral femoral cutaneous nerve dysfunction) | Pain and loss of sensation of lateral femoral cutaneous nerve on lateral aspect of thigh. | Clinical diagnosis. NCS is difficult to perform on this nerve. |

| Claudication | Pain in thigh and lower leg with exertion. Pain does not occur with lumbar spine extension. |

Suspected with exertional leg pain without back pain. Ultrasonography or angiography confirms arterial insufficiency. |

| Plexopathy | Back and leg pain that has a neuropathic character. Dysesthesias, burning, or electric sensation. Plexitis has no associated back pain. | Suspected when a patient has leg pain in more than one peripheral nerve distribution. MRI of plexus or CT of abdomen can show a structural lesion in some patients. |

| Radiculopathy | Pain largely in one dermatomal distribution. May be motor and reflex loss. Most patients have back pain, but not all. |

Suspected with pain radiating down one leg with or without back pain. Best imaged by MRI or postmyelographic CT. |

CT, Computed tomography; EMG, electromyography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NCS, nerve conduction studies.

Some basic guidelines for the differential diagnosis of lower back and leg pain are as follows:

Pain confined to the lower back generally is caused by a low back disorder.

Pain confined to the lower back generally is caused by a low back disorder.

Pain confined to the leg usually is caused by a leg disorder, although neuropathic pain from lumbar spine disease can radiate down the leg without back pain in a minority of patients.

Pain confined to the leg usually is caused by a leg disorder, although neuropathic pain from lumbar spine disease can radiate down the leg without back pain in a minority of patients.

Pain in both the low back and the leg usually is caused by lumbar radiculopathy or, less commonly, lumbosacral plexopathy.

Pain in both the low back and the leg usually is caused by lumbar radiculopathy or, less commonly, lumbosacral plexopathy.

Clinical abnormalities confined to one nerve root distribution usually are caused by intervertebral disk disease or lumbosacral spondylosis producing radiculopathy.

Clinical abnormalities confined to one nerve root distribution usually are caused by intervertebral disk disease or lumbosacral spondylosis producing radiculopathy.

Clinical abnormalities that involve several nerve distributions usually are caused by plexus lesions, with cauda equina lesions being the alternative diagnosis.

Clinical abnormalities that involve several nerve distributions usually are caused by plexus lesions, with cauda equina lesions being the alternative diagnosis.

Bilateral lesions suggest proximal damage in the spinal canal affecting the roots of the cauda equina.

Bilateral lesions suggest proximal damage in the spinal canal affecting the roots of the cauda equina.

Impairment of bladder control indicates either a cauda equina lesion or, less commonly, a bilateral sacral plexopathy.

Impairment of bladder control indicates either a cauda equina lesion or, less commonly, a bilateral sacral plexopathy.

Presence of more than one lesion may complicate neurological localization.

Presence of more than one lesion may complicate neurological localization.

Non-neurological causes of lower back pain are possible and particularly include urolithiasis, abdominal aortic aneurysm, and other intraabdominal pathological processes.

Non-neurological causes of lower back pain are possible and particularly include urolithiasis, abdominal aortic aneurysm, and other intraabdominal pathological processes.

Multiple lesions can make the differential diagnosis more difficult. For example, radiculopathies at two or more levels may look like a plexopathy or peripheral neuropathic process.

Multiple lesions can make the differential diagnosis more difficult. For example, radiculopathies at two or more levels may look like a plexopathy or peripheral neuropathic process.

Evaluation

Diagnostic evaluation of lower back and lower leg pain begins with proper clinical localization and classification of the complaint. Diagnostic tests are summarized in Table 30.6 (Russo, 2006). The tests used depend on the clinical presentation, as discussed later (see Clinical Syndromes).

Table 30.6 Diagnostic Studies for Lower Back and Lower Limb Pain

| Diagnostic Test | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) | Sensitive for identification of lumbar disk herniation, spinal stenosis, paravertebral mass in region of plexus, perineural tumors, and diskitis | May overemphasize structural lesions. May miss vascular lesions of spinal cord. Paravertebral disorders may be overlooked if they are not the focus of interest. Cannot be performed on patients with some implanted metallic and electrical devices. |

| Non-contrast computed tomography (CT) | Shows osteophytes and lateral disk herniations best. Can show bone fractures and extension of fragments into regions that may contain neural elements. | Cannot identify neural elements without intrathecal contrast. Disk herniations without bone involvement may be missed. |

| Myelography with postmyelographic CT | Many neurosurgeons consider this the definitive test for identification of lumbar disk herniation, osteophytes, and intervertebral foraminal stenosis. Postmyelographic CT should be routinely performed. | May miss far-lateral herniations. Is invasive with a small risk of serious adverse effects. |

| Nerve conduction studies (NCS) and electromyography (EMG) | Sensitive for identification of specific nerve root or peripheral neuropathic involvement | Patients may have clinically significant radiculopathy without EMG evidence of denervation (or vice versa if radiculopathy is old). |

| Diskogram | Can identify disk anatomy in comparison with bony and neural anatomy. May confirm disk level if it produces pain that reproduces patient’s complaints. | Invasive test, but risk of serious complications is low. Seldom performed in routine practice. |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI of the lumbosacral spine has the highest yield when the patient has back pain associated with radicular distribution of pain. Isolated back pain with no clinical symptoms or signs in the leg seldom is associated with significant findings on MRI. Intraspinal disorders that may not be revealed by MRI without contrast enhancement include neoplastic meningitis and some chronic infectious meningitides (Tan, Tsou, and Chee, 2002).

Clinical Syndromes

Lower Back and Leg Pain

Lumbar Spine Stenosis

Treatment can be conservative in the absence of neurological deficits. Physical therapy and medications can help, but surgical decompression is often required. Weakness of the legs or sphincter disturbance indicates a need for decompression. Although good evidence supports the benefit of surgical decompression in at least the short term, it is not clear that complex spine surgery with instrumentation produces substantial improvement in outcome (Gibson and Waddell, 2005).

Lumbosacral Radiculopathy

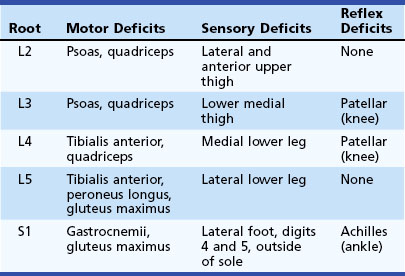

Patients present with back pain radiating down the leg in a distribution appropriate to the involved nerve root. The most common lumbosacral radiculopathy is of the S1 nerve root, produced by a lesion at the L5-S1 interspace. Table 30.7 presents the typical motor, sensory, and reflex deficits associated with lumbosacral radiculopathy at individual levels.

Plexopathy

Neoplastic Lumbosacral Plexopathy

Diagnosis is suspected with pain and often weakness in a leg associated with a known neoplasm. In such patients, the differential diagnosis often includes plexus infiltration, compression, and radiation plexopathy. MRI of the lumbar spine and plexus may show plexus involvement by tumor. EMG can help with differentiation of radiation plexopathy from neoplastic infiltration (Jaeckle, 2010).

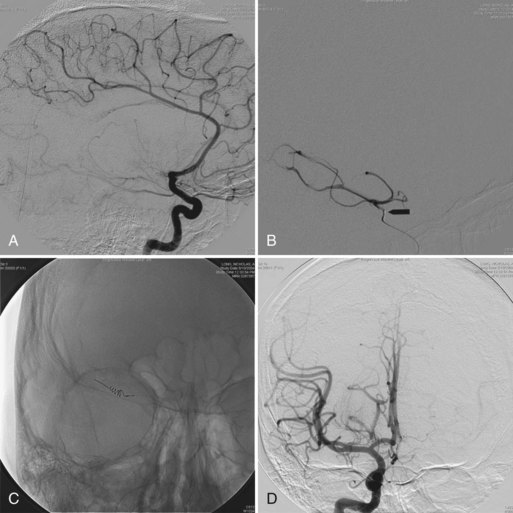

Plexus Injury from Retroperitoneal Hematoma

Retroperitoneal hematoma usually is caused by a bleeding disorder, a pelvic fracture, or abdominal surgery. Occasionally, bleeding from the site of arteriography can result in tracking of blood into the region of the lumbosacral plexus, especially after thrombolytic therapy or anticoagulation. Hematoma has also been described in patients after lumbar plexus block and may be delayed (Aveline and Bonnet, 2004).

Leg Pain without Lower Back Pain

Peripheral Nerve Syndromes

Meralgia Paresthetica

Treatment is conservative. Weight loss usually is effective in preventing recurrence. Anticonvulsants and tricyclic antidepressants are effective for control of the neuropathic pain. A nerve block may be supportive of the diagnosis in patients unresponsive to conservative measures. Surgery is rarely performed, and controversy about its indications and effectiveness is ongoing (Harney and Patijn, 2007; Haim, et al., 2006).

Piriformis Syndrome

Piriformis syndrome is an uncommon condition in which the sciatic nerve is compressed by the piriformis muscle in the posterior gluteal area. Hypertrophy of the piriformis muscle and other anatomical variants predispose affected persons to development of the syndrome. This condition may affect not only the main sciatic trunk but also the superior gluteal nerve. The diagnosis and even existence of this as a singular condition is controversial (Halpin and Ganju, 2009).

Piriformis syndrome is a clinical diagnosis. A patient with symptoms of sciatic neuropathy has typical clinical features on examination but no signs of radiculopathy or spinal stenosis on imaging. Spinal claudication can be confused with piriformis syndrome, so imaging of the spine usually is warranted. MRI neurography may show the lesion in many patients (Filler et al., 2005).

Peroneal Neuropathy

Peroneal neuropathy commonly is caused by compression of the nerve as it passes from the popliteal fossa across the fibular neck into the anterior compartment of the lower leg. Patients often present with foot drop from weakness of the tibialis anterior muscle. The diagnosis is confirmed by NCSs and EMG, with slowing of peroneal nerve conduction across the region of entrapment, usually across the fibular neck. The EMG shows evidence of active and chronic denervation in many patients, in keeping with the axonal damage indicated by the foot drop (Marciniak et al., 2005).

Peroneal neuropathy may be secondary to prolonged bed rest, or it may result from hyperflexion of the knee, usually from an occupational activity. The condition also may accompany peripheral neuropathy, predisposing to pressure palsy, or may be the result of a fibrous band attached to the peroneus longus, predisposing to nerve compression (Dellon, Ebmer, and Swier, 2002). In addition, pressure in obstetrical stirrups, prolonged sitting with crossed legs, cast on the lower leg for sprain or fracture, and stretch and compression by the contracted tibialis anterior muscle in ballet dancers all have been implicated. A fibrous band beneath the superficial head of the peroneus longus is found in a much larger proportion of patients with peroneal entrapment than in normal persons.

Polyneuropathy

Diagnosis usually is confirmed by NCS and EMG. Axonal neuropathy is more common than demyelinating neuropathy. Occasionally, patients with a predominantly small-fiber sensory neuropathy have normal NCS findings. Laboratory studies for peripheral neuropathy typically are performed as outlined in Chapter 31.

Treatment is with tricyclic antidepressants or anticonvulsants. Amitriptyline commonly is used for patients with small-fiber neuropathic pain. Anticonvulsants are used predominantly for patients with large-fiber neuropathic pain. When patients have symptoms of both, treatment with gabapentin, pregabalin, or oxcarbazepine can be helpful. Combination therapy with a tricyclic and anticonvulsant may be beneficial. Pure analgesics occasionally are used on a nightly basis to assist with sleep (Singleton, 2005).

Plexopathy

Lumbosacral Plexitis

Lumbosacral plexitis is similar to brachial plexitis, a presumed autoimmune process, but is less common. This entity is differentiated from radiculitis, which can be an inflammatory disorder of autoimmune or infectious origin (Tyler, 2008).

Lower Back Pain without Leg Pain

Facet Joint Pain Syndrome

Facet pain usually is treated with antiinflammatory agents and physical therapy. Avoidance of exacerbating activity usually is helpful. Facet blocks can be performed but often are not necessary, and effectiveness in terms of long-term relief is controversial (Varlotta et al., 2011). As part of physical therapy, traction can change the character of weight bearing on the joints. Physical therapy can strengthen paraspinal muscles and improve posture.

Lumbar Spine Osteomyelitis

The diagnosis of vertebral osteomyelitis is suggested by lower back pain in a patient who has not received radiation therapy, associated with systemic signs of infection—fever, elevated CRP concentration, and elevated white blood cell count (An and Seldomridge, 2006). MRI shows changes in the vertebral body and often in adjacent psoas muscle. Radiographs show degeneration of the disk margin of the vertebral body and disk space narrowing. Needle biopsy can reveal the causative organism in most cases. Open biopsy usually is not necessary. The diagnosis can easily be missed initially, since it can occur in patients with preexisting lumbar spine pain, and inflammatory signs may not be marked early on (Mylona et al., 2009).

Lumbar Diskitis

Diskitis is an inflammatory process affecting the intervertebral disks of any level, often occurring in the lumbar spine. In adults, Staphylococcus aureus and mycobacteria are important causes, although the list of potential pathogens is large. The causative organism typically reflects the source from which the bacteria spread—for example, skin infection, urinary tract infection, or intestinal infection. Diskitis associated with recent lumbar surgery is likely to be caused by resistant bacteria. In children, diskitis is also usually due to S. aureus, but extraspinal manifestations of infection are less likely (Early, Kay, and Tolo, 2003).

A diagnosis of lumbar diskitis is suggested by the presence of severe lower back pain without a radicular component, with tenderness and spasm of the paravertebral muscles associated with willingness of the patient to flex the hips but not the spine (Mikhael et al., 2009). Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and CRP concentration usually are increased. The diagnosis can be confirmed by MRI, which shows decreased signal intensity of the disk on T1-weighted images and increased signal intensity on T2-weighted images, often with changes in the end-plates of the adjacent vertebrae. Bone scan shows increased uptake in the region of the infected disk. Radiographs show disk space narrowing.

MRI is the most sensitive test for diskitis. Biopsy often is needed to identify an organism. Treatment begins with bed rest and antibiotics (Grados et al., 2007). Extensive surgery usually is not necessary; even tuberculous diskitis is successfully treated with antibiotics in more than 80% of cases (Bhojraj and Nene, 2002).

An H.S., Seldomridge J.A. Spinal infections: diagnostic tests and imaging studies. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;444:27-33.

Aveline, C., Bonnet, F. Delayed retroperitoneal haematoma after failed lumbar plexus block. Br J Anaesth. 2004;93(4):589-591. Epub 2004 Aug 20

Bhojraj S., Nene A. Lumbar and lumbosacral tuberculous spondylodiscitis in adults. Redefining the indications for surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:530-534.

Dellon A.L., Ebmer J., Swier P. Anatomic variations related to decompression of the common peroneal nerve at the fibular head. Ann Plast Surg. 2002;48:30-34.

Early S.D., Kay R.M., Tolo V.T. Childhood diskitis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2003;11:413-420.

Filler A.G., Haynes J., Jordan S.E., et al. Sciatica of nondisc origin and piriformis syndrome: diagnosis by magnetic resonance neurography and interventional magnetic resonance imaging with outcome study of resulting treatment. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;2:99-115.

Gibson, J.N., Waddell, G. 2005. Surgery for degenerative lumbar spondylosis, Cochrane Database Syst Rev, vol. 4, CD001352.

Grados F., Lescure F.X., Senneville E., et al. Suggestions for managing pyogenic (non-tuberculous) discitis in adults. Joint Bone Spine. 2007;74:133-139.

Haim A., Pritsch T., Ben-Galim P., et al. Meralgia paresthetica: a retrospective analysis of 79 patients evaluated and treated according to a standard algorithm. Acta Orthop. 2006;77:482-486.

Halpin, R.J., Ganju, A. Piriformis syndrome: a real pain in the buttock? Neurosurgery. 2009;65(4 Suppl):A197-A202.

Harney, D., Patijn, J. Meralgia paresthetica: diagnosis and management strategies. Pain Med. 2007;8(8):669-677.

Jaeckle, K.A. Neurologic manifestations of neoplastic and radiation-induced plexopathies. Semin Neurol. 2010;30(3):254-262.

Marciniak C., Armon C., Wilson J., et al. Practice parameter: utility of electrodiagnostic techniques in evaluating patients with suspected peroneal neuropathy: an evidence-based review. Muscle Nerve. 2005;31:520-527.

Mikhael, M.M., Bach, H.G., Huddleston, P.M., et al. Multilevel diskitis and vertebral osteomyelitis after diskography. Orthopedics. 2009;32(1):60.

Mylona, E., Samarkos, M., Kakalou, E., et al. Pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis: a systematic review of clinical characteristics. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2009;39(1):10-17.

Russo R.B. Diagnosis of low back pain: role of imaging studies. Clin Occup Environ Med. 2006;5:571-589. vi

Singleton J.R. Evaluation and treatment of painful peripheral polyneuropathy. Semin Neurol. 2005;25:185-195.

Tan D.Y.L., Tsou I.Y.Y., Chee T.S.G. Differentiation of malignant vertebral collapse from osteoporotic and other benign causes using magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2002;31:8-14.

Tyler, K.L. Acute pyogenic diskitis (spondylodiskitis) in adults. Rev Neurol Dis. 2008;5(1):8-13.

Varlotta, G.P., Lefkowitz, T.R., Schweitzer, M., et al. The lumbar facet joint: a review of current knowledge: Part II: diagnosis and management. Skeletal Radiol. 2011;40:149-157.

Wieser, S., Horisberger, B., Schmidhauser, S., et al. Cost of low back pain in Switzerland in 2005. Eur J Health Econ. 2010. [Epub ahead of print.]