92 Low Back Pain

• Nonspecific low back pain is usually self-limited and of short duration: about 60% of cases will resolve within 1 week and 90% within 2 to 6 weeks.

• Clues pointing to inflammatory, infectious, and oncologic disorders as possible causes of low back pain may be subtle and easily missed.

• Testing should be directed toward specific diagnostic concerns rather than screening studies.

• The primary treatment option for back pain is nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs along with judicious opioid use.

• Skeletal muscle relaxants and steroids have not been shown to improve outcomes and have significant side effects, although some patients do report relief.

• Patients who have pain longer than 2 weeks or in whom leg weakness, bowel or bladder dysfunction, fever, or new adverse symptoms develop at any time should be reevaluated.

Epidemiology

Most adults will experience LBP at some point in their lifetime, and about one in five adults experience LBP within a single year. LBP costs billions of dollars per year. About 85% to 90% of patients with LBP in a variety of outpatient settings are considered to have nonspecific LBP.1 This may lead to physician complacence in the evaluation of a presumably benign disorder.

Conversely, LBP can be incapacitating, and the patient may perceive the problem as a harbinger of death or disability, regardless of the cause. Patient expectations of a specific diagnosis of the pain source and a complete cure are rarely met and are probably unrealistic. Psychologic, social, and economic factors play a role in the natural history of many pain-related conditions, including progression of LBP from an acute to a chronic condition. LBP often becomes a chronic condition subject to exacerbations, akin to asthma and diabetes mellitus.2 These issues combine to make LBP a source of frustration for patients and physicians alike.

Pathophysiology

LBP is often classified as specific or nonspecific, mechanical or nonmechanical, or primary or secondary or is classified on the basis of presumed etiology (structural, neoplastic, referred pain or visceral, infectious, inflammatory, or metabolic). All these classification systems recognize that in the majority of cases a specific pathoanatomic diagnosis cannot be assigned. Indeed, clear correlation between a specific anatomic abnormality and pain is rarely established in patients, and proposed mechanisms of pain in the medical literature have been fraught with controversy. For example, many asymptomatic subjects have evidence of bulging, prolapsed, or herniated intervertebral disks.3

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

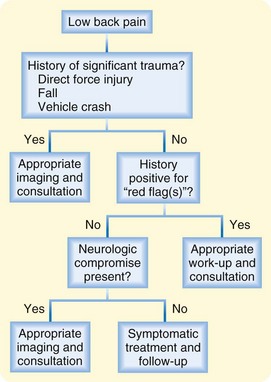

Nonmechanical causes must be distinguished from mechanical causes of LBP. The key to such distinction rests on eliminating systemic (infectious, neoplastic, metabolic, or inflammatory) and visceral causes. Figure 92.1 shows one diagnostic approach, and Box 92.1 lists the differential diagnosis for LBP.

Box 92.1

Differential Diagnosis of Low Back Pain*

Mechanical Lower Back or Leg Pain (97%)†

Nonmechanical Spine Conditions (≈1%)**

From Jarvik JG, Deyo RA. Diagnostic evaluation of low back pain with emphasis on imaging. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:586–97.

* Figures in parentheses indicate the estimated percentages of patients with these conditions among all adult patients with low back pain in primary care. Diagnoses shown in italics are often associated with neurogenic leg pain. Percentages may vary substantially according to demographic characteristics or referral patterns in a practice. For example, spinal stenosis and osteoporosis are more common in geriatric patients, spinal infection in injection drug users, and so forth.

† The term mechanical is used here to designate an anatomic or functional abnormality without underlying malignant, neoplastic, or inflammatory disease. Approximately 2% of cases of mechanical low back or leg pain are accounted for by spondylolysis, internal disk disruption, or discogenic low back pain and presumed instability.

‡ Strain and sprain are nonspecific terms with no pathoanatomic confirmation. Nonspecific low back pain or idiopathic low back pain may be a preferable term.

§ Spondylolysis is as common in asymptomatic persons as in those with low back pain; thus its role in causing low back pain remains ambiguous.

¶ Internal disk disruption is diagnosed by provocative diskography (injection of contrast material into a degenerated disk with assessment of pain at the time of injection). However, diskography often causes pain in asymptomatic adults, and the condition in many patients with positive diskogram findings improves spontaneously. Thus the clinical importance and appropriate management of this condition remain unclear. The term diskogenic lower back pain is used more or less synonymously with the term internal disk disruption.

¶ Presumed instability is loosely defined as greater than 10 degrees of angulation or 4 mm of vertebral displacement on lateral flexion and extension radiographs. However, the diagnostic criteria, natural history, and surgical indications remain controversial.

** Scheuermann disease and Paget disease of bone probably account for less than 0.01% of nonmechanical spinal conditions.

Specific causes of LBP are shown in Table 92.1, together with red flag signs or symptoms suggesting these diagnoses. When the history and physical examination suggest a nonmechanical cause of LBP, appropriate diagnostic testing or specialty consultation (or both) is necessary to confirm or rule out the suspected specific cause or causes.

Table 92.1 “Red Flags” in the History and Physical Examination of Patients with Low Back Pain

| DISORDER | HISTORY | PHYSICAL EXAMINATION |

|---|---|---|

| All | Duration of pain >1 mo Bed rest with no relief Age < 20 or >50 yr* |

|

| Cancer | Age ≥ 50 yr Previous cancer history Unexplained weight loss† |

Neurologic findings‡ Lymphadenopathy |

| Compression fracture | Age ≥ 50 years (≥60 yr more specific) Significant trauma§ History of osteoporosis Corticosteroid use Substance abuse‖ |

Fever (>100° F [38° C]) Tenderness of spinous processes |

| Infection | Fever or chills Recent skin or urinary infection Immunosuppression Injection drug use |

|

| Inflammatory arthritis | Insidiously causing pain for >3 mo Bed rest with no relief Morning stiffness improved with activity |

* Age younger than 20 years is associated with increased risk for spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis, and stress fractures; age older than 50 years suggests increased risk for cancer and compression fractures.

† Unexplained weight loss is defined as more than 10 lb over the preceding 6 months.

‡ Most commonly caused by a herniated lumbar disk or lumbar spinal stenosis rather than malignancy.

§ Significant trauma is a fall from a height or external trauma such as a motor vehicle accident.

‖ Substance abuse can increase the risk for fracture through higher rates of trauma. Alcohol abuse can also increase the risk for fracture as a result of decreasing bone density.

Adapted from Atlas SJ, Deyo RA. Evaluating and managing acute low back pain in the primary care setting. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:120–31.

Systemic causes of LBP are disease processes that involve the structures of the spinal column, including cancer, infection, inflammation, and degenerative processes. Cancer (with metastatic or primary tumor invasion of the spinal column) typically occurs in those older than 50 years. Weight loss, pain with bed rest, and failure of therapy (with pain lasting a month or longer) are frequent symptoms. Back pain in any patient with a history of cancer should be considered to be due to a cancerous lesion of the spine until ruled out.4

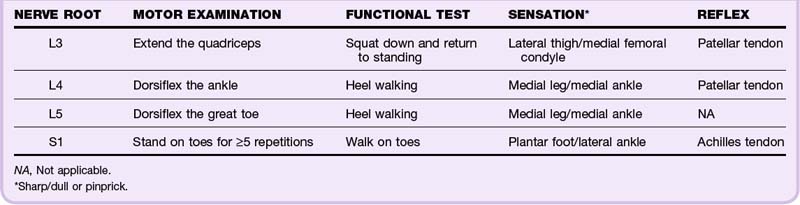

LBP can be associated with leg pain secondary to radiating pain, but other causes include sciatica (or lumbosacral radiculopathy) with pain radiating from the back to the buttock and posterior or lateral aspect of the leg. Sciatica is frequently caused by lumbar degenerative disk disease. True sciatica usually causes pain below the knee; at least 95% of degenerative disks in the lumbar spine occur at the L4-L5 and L5-S1 vertebral levels. For this reason, the neurologic examination should be focused on both sensory and motor testing of the lumbosacral nerve roots. Table 92.2 details the motor, sensory, and reflex test components of the neurologic examination of patients with LBP. Note that functional strength testing is more likely than simple motor testing to detect subtle muscle weakness.

Passive straight leg raise (SLR) testing appears to help in the diagnosis of sciatica by stretching the sciatic nerve. A positive ipsilateral SLR test (which results in pain below the knee when the leg to which LBP radiates is raised higher than 30 to 60 degrees with the patient supine) is sensitive but not specific for sciatica, whereas a positive crossed SLR test (in which pain in the affected leg is provoked or worsened when the contralateral leg is raised) is specific but insensitive.5 A negative SLR test may be of greater value because patients with this finding generally have good long-term outcomes.

Cauda equina syndrome (CES) results from compression of the conus medullaris of the spinal cord or the nerve roots that make up the cauda equina. It is typically caused by a large central disk herniation but can also be due to other space-occupying lesions such as spinal stenosis, tumor, SEA, and hematoma.2 The most consistent findings in patients with CES are LBP, urinary symptoms, and sacral and perineal (“saddle”) paresthesias.6 Bilateral sciatica is also a concerning symptom. Central disk herniations may not cause sciatica, and back pain may be a minor component of the patient’s symptoms. The presence of urinary retention has good sensitivity and specificity for CES.7 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is diagnostic and usually shows severe spinal canal impingement by a disk.

Expeditious diagnosis and therapy may help maximize the long-term outcome (in terms of pain and disordered bladder, bowel, and sexual function) in these patients. Despite some controversy regarding the role of impairments already present at diagnosis, there appears to be some improvement in the outcome of CES if decompression is performed within 48 hours of arrival in the emergency department (ED).8

Children have back pain at higher rates than previously appreciated and are at higher risk for spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis, especially adolescent and teenage athletes. A one-legged hyperextension test may help diagnose these conditions. Bone scans using single-photon emission computed tomography may be the most appropriate initial test, assuming that the findings on plain radiography are normal.9

The Waddell signs have been promoted as tools to help demonstrate a “nonorganic” cause of patients’ symptoms, but they are mainly useful for predicting patients at risk for prolonged recovery from LBP.10 Waddell signs may also point to a diagnosis of depression or another psychoneurosis.

Diagnostic Testing

Plain films of the lumbosacral spine, rectal examination, postvoid residual bladder volume, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and MRI are useful diagnostic adjuncts in the ED (Table 92.3). Other studies such as myelography (plain or computed tomographic [CT]), electromyography, and diskography should be obtained at the discretion of consultants.

| TEST | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| Plain radiography | Reserve for <15 OR >50 yr old OR significant trauma* |

| Rectal examination | To check for neurologic compromise OR a prostate mass |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | >20 mm/hr is concerning in patients with possible infection or cancer† |

| Postvoid residual bladder volume | >100-200 mL implies possible CES; bladder scan accurate to ±25 mL‡ |

| Magnetic resonance imaging | Reserve for suspected CES, SEA, or spinal cord compression§ |

CES, Cauda equina syndrome; SEA, spinal epidural abscess.

* Deyo RA, Weinstein JN. Low back pain. N Engl J Med 2001;344:363–70.

† Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM. Screening for malignancy in low back pain patients: a systematic review. Eur Spine J 2007;16:1673–9.

‡ Small SA, Perron AD, Brady WJ. Orthopedic pitfalls: cauda equina syndrome. Am J Emerg Med 2005;23:159–63.

§ Gilbert FJ, Grant AM, Gillan MG, et al. Low back pain: influence of early MR imaging or CT on treatment and outcome—multicenter randomized trial. Radiology 2004;231:343–51.

Treatment

Hospital Management

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain

Establish the absence of a systemic or visceral source of the pain.

Rule out fracture and orthopedic instability.

Check for neurologic compromise, especially cauda equina syndrome.

Treat specific systemic, visceral, and orthopedic diseases as indicated.

Use conservative therapy for nonspecific back pain.

Manage patient expectations regarding nonspecific back pain.

Counsel patients regarding concerning symptoms accompanying the pain.

Nonspecific LBP is usually self-limited and of short duration: about 60% of cases will resolve within 1 week and 90% within 2 to 6 weeks. Treatment is conservative. Acetaminophen and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are first-line analgesics; they are usually prescribed for all patients who do not have contraindications.11 Patients should be instructed to use NSAIDs routinely because administration only as needed does not seem to be as effective. Narcotic administration is restricted to patients with severe pain and only for short courses. Narcotics are not more beneficial than other medications for acute or subacute LBP and may lead to higher rates of chronic pain.12 See Table 92.4 for other treatment modalities.

Table 92.4 Treatment of Nonspecific Low Back Pain and Sciatica

| TREATMENT | EVIDENCE-INFORMED CONSIDERATIONS |

|---|---|

| Medications | |

| Acetaminophen | As effective as NSAIDs for short-term pain relief* |

| NSAIDs | Offer modest short-term pain relief* |

| Skeletal muscle relaxants | No improvement in outcomes; have significant side effects† |

| Corticosteroids | No improvement in outcomes; have significant side effects‡ |

| Narcotic analgesics | Not recommended by guidelines; may foster chronic pain§ |

| Nonpharmacologic Modalities | |

| Symptom-limited activities of daily living | Equal or superior to bed rest or specific therapeutic exercise‖ |

| Self-paced walking | Seems to reduce recurrence and speed recovery¶ |

| Superficial heat | Good evidence for moderate relief of low back pain** |

NSAIDs, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs.

* Roelofs PD, Deyo RA, Koes BW, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain: an updated Cochrane review. Spine 2008;33:1766–74.

† Turrurro MA, Frater CR, D’Amico FJ. Cyclobenzaprine with ibuprofen versus ibuprofen alone in acute myofascial strain: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Ann Emerg Med 2003;41:818–26.

‡ Holve RL, Barkan H. Oral steroids in initial treatment of acute sciatica. J Am Board Fam Med 2008;21:469–74.

§ Wevster BS, Verma SK, Gatchel RJ. Relationship between early opioid prescribing for acute occupational low back pain and disability duration, medical costs, subsequent surgery and late opioid use. Spine 2007;32:2127–32.

‖ Dahm KT, Brurberg KG, Jamtvedt G, et al. Advice to rest in bed versus advice to stay active for acute low-lack pain and sciatica. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;6:CD007612.

¶ Sculco AD, Paup DC, Fernhall B, et al. Effects of aerobic exercise on low back pain patients in treatment. Spine J 2001;1:95–101.

** Ghou R, Huffman LH. Nonpharmacologic therapies for acute and chronic low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:492–504.

Patients frequently prefer “alternative” modes of therapy (e.g., chiropractic or osteopathic spinal manipulation, acupuncture, massage, magnets) over traditional allopathic approaches. In most cases there are neither proven benefits nor drawbacks to these therapies13; however, patients will often use them regardless of physician recommendations. Risk for CES may be increased following manipulation in patients with disk disease, tumors, or other specific diseases of the spinal column.

Admission and Discharge

Patients with nonspecific LBP can be discharged home in almost all circumstances; there appears to be limited need or utility in admitting patients for pain control. All patients with LBP who are discharged from the ED should be warned about the risk for CES and be told to return if they experience neurologic or bowel or bladder symptoms.14

Patients with specific systemic or visceral sources of their LBP require specialist consultation.

![]() Documentation

Documentation

Presence or absence of “red flags” suggesting specific, systemic, or visceral sources of the patient’s complaints

Findings from a systematic neurologic examination of the lower extremities, including sacral nerve function

Discussion of findings requiring urgent work-up, including consultations (because of a possible specific cause, neurologic compromise, or spinal instability)

Discussions with patients and their families or friends (specific instructions about follow-up and warning signs suggesting cauda equina syndrome requiring immediate evaluation)

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Low back pain is a common problem, with four of every five adults having back pain at some time in their lifetime.

The most common causes of low back pain are:

Treatment of low back pain (what doctors call “conservative therapy”) includes:

Follow up with your primary care provider to make sure that you are getting better and to help minimize recurrence of your symptoms. If you have back pain plus any of the following signs or symptoms, call your doctor:

1 Manek NJ, MacGregor AJ. Epidemiology of back disorders: prevalence, risk factors, and prognosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17:134–140.

2 Deyo RA, Weinstein JN. Low back pain. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:363–370.

3 Jensen MC, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Obuchowski N, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:69–73.

4 Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM. Screening for malignancy in low back pain patients: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:1673–1679.

5 van der Windt DA, Simons E, Riphagen II, et al. Physical examination for lumbar radiculopathy due to disc herniation in patients with low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2010. CD007431

6 Jalloh I, Minhas P. Delays in the treatment of cauda equina syndrome due to its variable clinical features in patients presenting to the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2007;24:33–34.

7 Small SA, Perron AD, Brady WJ. Orthopedic pitfalls: cauda equina syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23:159–163.

8 Qureshi A, Sell P. Cauda equina syndrome treated by surgical decompression: the influence of timing on surgical outcome. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:2143–2151.

9 Auerbach JD, Ahn J, Zgonis MH, et al. Streamlining the evaluation of low back pain in children. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:1971–1977.

10 Waddell G, McCulloch JA, Kummel E, et al. Non-organic physical signs in low-back pain. Spine. 1980;5:117–125.

11 Roelofs PD, Deyo RA, Koes BW, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain: an updated Cochrane review. Spine. 2008;33:1766–1774.

12 Webster BS, Verma SK, Gatchel RJ. Relationship between early opioid prescribing for acute occupational low back pain and disability duration, medical costs, subsequent surgery and late opioid use. Spine. 2007;32:2127–2132.

13 Assendelft WJ, Morton SC, Yu EI, et al. Spinal manipulative therapy for low back pain. A meta-analysis of effectiveness relative to other therapies. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:871–881.

14 Kostuik JP. Medicolegal consequences of cauda equina syndrome: an overview. Neurosurg Focus. 2004;16:e8.