17 Loss of appetite and loss of weight

Case

A 64-year-old man presents with a 3-month history of upper abdominal pain associated with weight loss and mild diarrhoea. He describes the pain as a dull ache and, on specific questioning, says it radiates straight through to the back. The pain is sometimes made worse by eating, and comes and goes. He has lost about 8 kilograms in the last 3 months. He has had, up to three times daily, loose stools which are more smelly than normal, but are not pale and flush away without difficulty. He has lost his appetite. He has not noticed dark urine or pale stools. There is no history of arterial or venous thrombosis or embolism. An upper endoscopy 1 month ago was normal based on the report brought by the patient. He is an ex-smoker, having ceased 10 years ago. He has otherwise been in good health. There is no family history of gastrointestinal disease.

Introduction

Weight loss is defined as a state when the caloric output (from the basal metabolic rate and voluntary activities) exceeds the input. Weight loss that equals or exceeds 5% of body weight (or 4.5 kg) over a 6-month period is arbitrarily defined as clinically significant. Most individuals can sustain a loss of 5–10% of their body weight without any significant health consequences. In a hospital or institutional setting, patients who have lost weight have increased morbidity and mortality, particularly elderly patients and cancer patients. Those who have lost 5 kg or more in the preceding 6 months also have an increased postoperative morbidity and mortality.

Pathophysiology of Anorexia and Weight Loss

Anorexia

Anorexia alone is not a symptom of diagnostic value and can occur in many gut and systemic diseases (Box 17.1). Anorexia should be differentiated from ‘sitophobia’, which is a term used to describe a fear of food because of subsequent abdominal pain. Sitophobia can occur with chronic mesenteric vascular insufficiency (abdominal angina) or small intestinal Crohn’s disease with partial obstruction. Anorexia should also be distinguished from early satiation (a feeling of fullness after eating a small amount such that a normal meal cannot be finished), such as occurs after a partial gastrectomy and in patients whose gastric fundus fails to relax (e.g. after a vagotomy, and in some patients with functional dyspepsia).

Weight loss

Involuntary weight loss is a common manifestation of a variety of disease processes (Table 17.1). Although the precise pathophysiological mechanisms inducing weight loss are unclear, multiple factors have been implicated.

| Cause | Examples |

|---|---|

| Medical conditions | |

| Malignancy | Carcinoma of the pancreas, stomach, oesophagus, colon, liver, lung, breast, kidney |

| Gastrointestinal and liver disease | Malabsorptive states, inflammatory bowel disease, secondary to dysphagia, pancreatitis, hepatitis |

| Cardiovascular disease | End-stage heart failure |

| Respiratory disease | End-stage respiratory failure |

| Renal disease | Chronic kidney disease |

| Endocrine disease | Hyperthyroidism (and hypothyroidism-induced anorexia in elderly patients), hyperparathyroidism, diabetes mellitus, panhypopituitarism, Addison’s disease, phaeochromocytoma |

| Connective tissue disease | Scleroderma, rheumatoid arthritis |

| Infections | HIV, tuberculosis, pyogenic abscess, infective endocarditis, atypical Mycobacterium, systemic fungal infections |

| Neurological disease | Stroke, dementia, Parkinson’s disease |

| Drugs | Amphetamines, cocaine, opiates, serotonin reuptake inhibitors |

| Psychiatric conditions | |

| Depression | |

| Anorexia nervosa | |

| Bulimia nervosa | |

| Alcoholism | |

| Neuroleptic-withdrawal | |

| Miscellaneous conditions | |

| Oral disorders | Ill-fitting dentures, candidiasis, gingivitis |

| Hyperemesis gravidarum | |

Cancer patients may be unable to eat or may not feel like eating (secondary to treatment or depression). Failure to down-regulate energy expenditure in the face of decreased caloric intake can lead to energy imbalance, which may be one of the main mechanisms of weight loss in some cancers. Increased caloric utilisation by tumour tissue may also be a factor, although increases in resting energy expenditure have not been shown to occur in all patients with tumours. In the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), poor oral intake, malabsorption, tumour development and repeated infections coupled with a relatively high resting energy expenditure may all have a role. In elderly people, preferential oxidation of fatty acids and an increase in anaerobic glucose metabolism result in inefficient expenditure or wastage of adenosine triphosphate.

Clinical Approach to Anorexia and Weight Loss

The differential diagnosis is extensive (Box 17.1 and Table 17.1), but investigations should be directed by the history and physical examination.

History

Weight loss does not always accompany anorexia. Patients may actually have weight loss with an increase in appetite in malabsorption, hyperthyroidism, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, phaeochromocytoma or occasionally with lymphoma or leukaemia.

Ask whether the patient is afraid to eat because eating precipitates pain or other gastrointestinal symptoms. Abdominal pain that usually occurs after eating suggests peptic ulcer disease, chronic pancreatitis or chronic mesenteric ischaemia (abdominal angina). Pain after eating may also occur in patients with the irritable bowel syndrome or functional dyspepsia (Chs 6 and 7).

In elderly patients, poor dentition is a common but often overlooked problem. Oral disease resulting from conditions such as vitamin deficiencies, candidiasis or gingivitis can affect mastication. Ask about alterations in taste (dysgeusia), which may make food seem unpalatable. Zinc deficiency may sometimes be responsible for dysgeusia (Ch 3).

Ask about previous medical conditions (e.g. pulmonary tuberculosis, renal disease, previous cancer, cardiac disease) and past surgery. Postgastrectomy syndromes can cause malabsorption (Ch 6). Prior abdominal surgery causes adhesions that can lead to chronic incomplete intestinal obstruction.

Physical examination

Examine for specific features of vitamin and mineral deficiencies (Table 17.2). Glossitis, cheilosis or perioral dermatitis can result from deficiency of vitamins such as riboflavin, pyridoxine or niacin, whereas peripheral neuropathy or ataxia can occur due to lack of thiamine or vitamin B12.

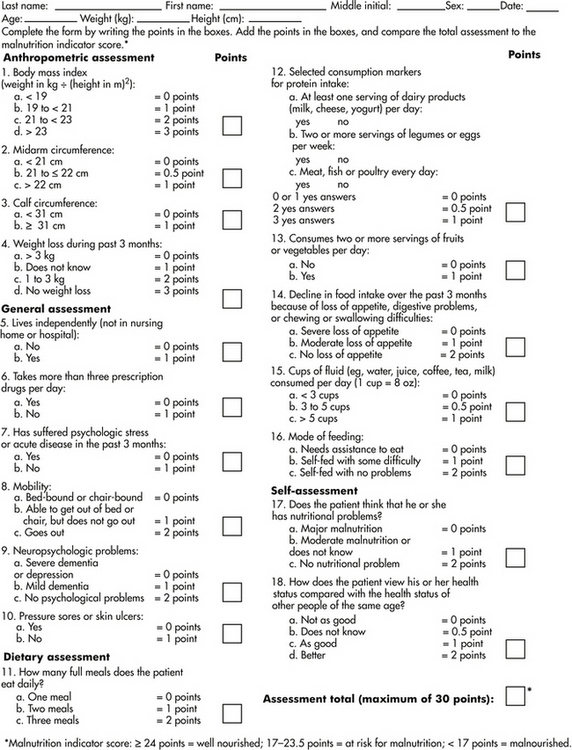

Figure 17.1 Mini nutritional assessment

Reproduced with permission from Guigoz, Y, Vellas, B, Garry, PJ. Assessing the nutritional status of the elderly: The Mini Nutritional Assessment as part of the geriatric evaluation. Nutr Rev 1996; 54(1 Pt 2):S59. Copyright © 1996 International Life Sciences Institute.

Next, conduct a careful gastrointestinal examination. For instance, in a patient with weight loss and jaundice (Ch 23), a pancreatic cancer with biliary obstruction may be the explanation. If stigmata of chronic liver disease are present and abdominal examination reveals a liver mass with or without a bruit, cirrhosis with development of a hepatoma should be considered. Large abdominal masses can occasionally compress the stomach or small bowel, inducing anorexia (Ch 19).

Investigations

The diagnostic work-up needs to be directed towards defining the extent of malnutrition and detecting the underlying cause of weight loss.

Tests to estimate nutritional status

Calculate the BMI (Box 17.2). Other anthropometric measurements include triceps skin-fold thickness and mid-arm muscle circumference to assess the fat reserve and the muscle mass of the body, respectively. These quantitative measurements are useful for follow-up of nutritional status.

Box 17.2 Classification of nutritional status by body mass index (BMI)

| < 16.0 | Severely malnourished |

| 16–16.9 | Moderately malnourished |

| 17–18.4 | Mildly malnourished |

| 18.5–24.9 | Normal |

The prognostic nutritional index predicts the likelihood of developing postoperative complications in patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery. It is based on a simple linear equation incorporating measurements of serum proteins (albumin and transferrin concentration), subcutaneous fat (triceps skin fold), and immunologic function (delayed skin hypersensitivity).

In the elderly, the mini-nutritional assessment is a valid tool that allows subdivision of patients into nourished, malnourished or at risk of malnutrition (Fig 17.1).

Table 17.2 Clinical findings associated with vitamin and mineral deficiencies

| Findings on physical examination | Associated vitamin deficiencies |

|---|---|

| Mucocutaneous | |

| Dermatitis/cheilosis/glossitis | Riboflavin (B2), pyridoxine (B6), niacin |

| Bleeding/swollen gums | Vitamin C |

| Petechiae/ecchymoses | Vitamins C and K |

| Perifollicular haemorrhages/keratitis | Vitamin C |

| Rash (face/body: pustular, bullous, vesicular, seborrhoeic, acneiform), skin ulcers, alopecia | Zinc |

| Neurological | |

| Peripheral neuropathy | Thiamine/vitamin B12, chromium, vitamin E |

| Dementia/confusion | Thiamine/niacin, zinc, manganese |

| Night blindness | Vitamin A |

| Ophthalmoplegia | Thiamine |

| Haematological | |

| Pallor (anaemia) | Vitamin B12/folic acid, iron, copper |

| Miscellaneous | |

| Dysgeusia | Zinc |

| Fractures | Vitamin D |

| Loosening of teeth, periosteal haemorrhages | Vitamin C |

| Cardiac failure/cardiomyopathy | Thiamine, selenium |

| Hypothyroidism | Iodine |

Tests aimed at detecting the cause

Diagnostic tests can be arbitrarily classified into those of a screening nature and those that target specific abnormalities detected by the history, physical examination or initial screening test results (Table 17.3). The tests are most successful in finding the cause when they are directed by the history and examination findings.

Table 17.3 Investigations for weight loss and examples of diseases to consider

| Diagnostic test | Examples of diseases screened |

|---|---|

| Bedside tests | |

| Urine analysis | Renal cell cancer |

| Laboratory tests | |

| Routine | |

| Full blood count and iron studies | Iron deficiency anaemia from gastrointestinal blood loss |

| Folate/vitamin B12 | Macrocytic anaemia in bacterial overgrowth |

| Electrolytes | Chronic kidney disease, Addison’s disease |

| Liver function tests | Chronic liver disease |

| Calcium/phosphate | Hyperparathyroidism, bony metastases |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein | Autoimmune disease, inflammatory bowel disease, malignancy |

| Specific | |

| Anti-nuclear antigen | Autoimmune disease, e.g. systemic lupus, scleroderma |

| Rheumatoid factor/anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Thyroid function tests | Hyper/hypothyroidism |

| Tumour markers | (See Box 17.3) |

| Imaging tests | |

| Chest x-ray | Lung cancer, tuberculosis |

| Barium studies of small bowel/small bowel capsule/enteroscopy | Crohn’s disease |

| CT scan chest/abdomen/pelvis Magnetic resonancecholangio-pancreatography |

Empyema, lung/ovarian/liver cancers Bile duct/pancreatic cancer |

| Invasive tests | |

| Gastroscopy, colonoscopy | Peptic ulcer, oesophagus/stomach/colon cancers |

| Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography | Pancreatic cancer, cholangiocarcinoma, ampullary tumour |

| Laparoscopy, laparotomy | Crohn’s disease, internal malignancies |

| Fine needle aspiration | Liver/breast/thyroid/lymph node cancers |

Routine tests are inexpensive, and may help to identify the basic nature of the problem. A full blood count can detect evidence of iron deficiency anaemia, which may suggest blood loss from a gastrointestinal tract cancer. A high erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein may suggest inflammation or malignancy. Electrolyte and creatinine tests can identify chronic kidney disease as a cause of anorexia. Liver function tests can be helpful (e.g. elevated transaminase levels in hepatitis, obstructive jaundice due to pancreatic cancer or hypoalbuminaemia in malignancy or chronic liver disease). A serum calcium may detect hypercalcaemia caused by a malignancy. A bedside urine analysis may detect proteinuria (e.g. nephrotic syndrome) or haematuria. In the absence of infection or stones, persistent haematuria may indicate renal or bladder cancer. A positive result of a stool occult blood test may indicate colorectal neoplasia or inflammatory bowel disease, but this test has low sensitivity and specificity and is less often done (Ch 10). If malabsorption is suspected, then an appropriate work-up should be done (Ch 14). A thyroid-stimulating hormone test will detect hyperthyroidism and fasting blood sugar level test, diabetes mellitus. Tumour markers may occasionally help point towards a correct diagnosis in difficult cases but are of most use in following response to treatment (Box 17.3).

Box 17.3 Causes of elevated levels of tumour markers

Carcinoembryonic antigen

Alpha fetoprotein

CA-125

CT scans of the chest and abdomen provide excellent anatomical definition and objective assessment which is not operator dependent. They are extremely useful for defining mediastinal and retroperitoneal pathologies. Mediastinal widening seen on chest x-ray films in small cell lung cancer, lymphoma or thymoma can be delineated further with a chest CT scan. Similarly, metastatic lymph notes in the mesentery or in the retroperitoneum, or organomegaly detected on clinical examination can be accurately defined by an abdominal CT scan. Although CT should be reserved for localising a suspected lesion, this test is increasingly used for screening when no diagnosis is forthcoming. Ultrasound examination can provide valuable information about biliary anatomy or pelvic pathology (Ch 19). Mammography should be done in women if breast cancer is a consideration.

Management of Patients with Weight Loss

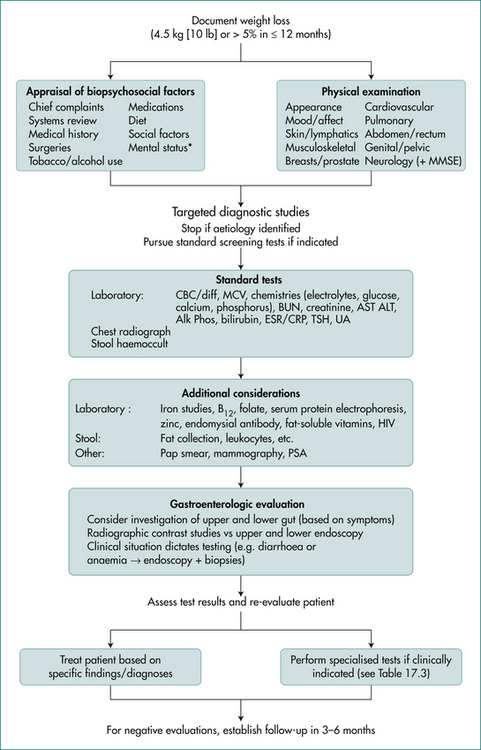

A summary of an approach is presented in Figure 17.2.

Empiric therapy has a place in stimulating appetite and increasing weight in patients with end-stage cancer and AIDS. Cyproheptadine, a serotonin antagonist, has been extensively used in both adults and children and may be of benefit in a few cases. Corticosteroids have an established role in stimulating appetite and improving the sense of well-being in patients with malignancies. However, steroids have side effects and do not usually result in non-fluid weight gain (e.g. increased muscle bulk). Megesterol is a synthetic progestin that is an antiemetic with an appetite-stimulating effect. It is helpful in increasing oral food intake and non-fluid weight gain in patients with AIDS. This medication is usually well tolerated but is expensive.

Nutritional Support

Enteral feeding

Another specific problem associated with nasogastric or nasoenteric feeding is gastro-oesophageal reflux. Aspiration is also an important complication. Patients with symptomatic aspiration (e.g. aspiration pneumonia) may benefit from elevation of the head end of the bed during and post feeding, and the avoidance of bolus feeding. If aspiration occurs with a PEG despite the incorporation of the above regimen, a revision to jejunostomy tube feeding should be considered. Placement of the tube beyond the pylorus reduces, but does not overcome, this complication. The main indications for use of jejunostomy feeding over gastrostomy include tracheal aspiration, gastroparesis and a partial or total gastrectomy.

Total parenteral nutrition

While the enteral route is always preferable, total parenteral nutrition (TPN) is required when anatomical or physiological abnormalities of the gut preclude enteral feeding. In clinical practice, the most common indications are protracted periods of non-functioning bowel (e.g. major abdominal sepsis). Short gut syndrome occurs infrequently, but requires long-term TPN. Preoperative TPN is of no benefit in healthy patients or even those with mild-to-moderate malnutrition. Indications for TPN are summarised in Box 17.4.

Complications related to TPN can be either local (related to insertion and maintenance of the central venous catheter) or systemic (related to the infusion itself). In patients receiving TPN, local defence barriers may break down, allowing bacterial colonisation and systemic seeding. Strict asepsis and insertion by experienced personnel, followed by patient education in the care of the line, should minimise local complications. Long (peripherally inserted central catheter) lines placed through, for example, the brachial vein to just above the right atrium can be left in place up to a year before needing replacement. As metabolic derangements are frequent, close monitoring by a dedicated TPN team is preferable. The complications are summarised in Box 17.5.

The refeeding syndrome occurs with overly aggressive nutritional replacement. Severe hypophosphataemia occurs because carbohydrates given enterally or intravenous glucose stimulates insulin, leading to phosphate shifts into cells. Irritability and hyperventilation followed by profound muscle weakness, acute rhabdomyolysis, seizures and respiratory failure (from diaphragm paralysis) then death can occur. Alcoholics who are malnourished are at particular risk; the refeeding syndrome can then occur after starting a normal diet. It is therefore very important to give adequate supplemental phosphate in these settings unless renal function is impaired.

Diseases Associated with Weight Loss

Some common gastrointestinal cancers, and anorexia and bulimia nervosa are discussed here. Other diseases are covered elsewhere (e.g. malabsorption: Ch 14).

Adenocarcinoma of the pancreas

Adenocarcinomas arising from ductal cells constitute 90% of all cases of pancreatic cancer. Islet cell tumours, acinar cell tumours, and cystadenocarcinomas account for most of the remaining 10% of cases (see Ch 26). The incidence appears to be on the increase, with carcinoma of the pancreas being the second most common gastrointestinal malignancy (after colon cancer).

Pathogenesis

The exact aetiopathogenesis is unclear. It is rare before age 45 years and is more common in men and people of African descent. Increasing age (over 60 years) is a risk factor. Chronic pancreatitis and hereditary chronic pancreatitis (autosomal dominant due to a mutation in the cationic trypsinogen gene (PRSS1), Ch 6), and some familial cancer syndromes (e.g. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome) are of established importance. Smoking, diabetes mellitus, obesity, increased dietary fat, partial gastrectomy and Helicobacter pylori are also risk factors. There is no convincing evidence that coffee intake is a causal factor.

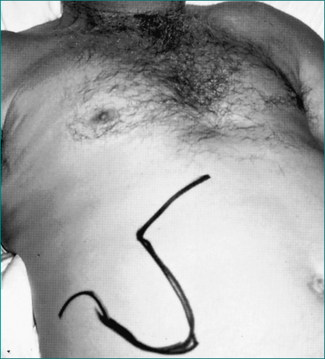

Clinical features

Jaundice due to biliary obstruction is found in the majority of patients with cancer of the pancreatic head. Pruritus is often associated. The gall bladder is usually enlarged in patients with cancer of the pancreatic head, but is impalpable in more than 50% (Courvoisier’s law: if the gall bladder is enlarged and the patient is jaundiced, the cause is unlikely to be gallstones) (Fig 17.3).

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is initially suggested by demonstrating a mass in the pancreas or by dilated bile ducts. On ultrasound scan, this is characteristically hypoechoic. On CT scan, the mass is usually of reduced density compared with the rest of the pancreas. If the tumour is in the head of the pancreas, it commonly produces dilatation of the common bile duct and the main pancreatic duct (the double-duct sign). Lymphatic metastases may be apparent as masses in the porta hepatis. Liver metastases may also be apparent.

Helical CT combined with intravenous contrast (CT angiograph) helps evaluate for resectability.

Histological diagnosis is mandatory for confirmation of the tumour and to rule out focal pancreatitis, autoimmune pancreatitis or other neoplasms, such as lymphoma, islet cell tumours and cystadenocarcinoma, where the prognosis and therapeutic options are significantly different (Ch 26).

The cancer-associated antigen (CA-19-9) is often elevated in advanced disease.

Treatment

Islet cell pancreatic neoplasms

A gastrinoma will cause peptic ulcer disease as part of the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (Ch 6), and can be found in the pancreas (25%) or duodenum (50%). Two-thirds of cases with a vasoactive intestinal polypeptide secreting tumour occur in the pancreas and over 50% are malignant; this causes a severe secretory diarrhoea (‘pancreatic cholera’). An insulinoma causes hypoglycaemia, but is very rare (insulin and C-peptide are both high during hypoglycaemic episodes). A glucagonoma is also very rare but has a distinctive presentation: it causes weight loss, hyperglycaemia and a scaly red rash (necrolytic erythema).

Carcinoma of the oesophagus

Treatment

Apart from early oesophageal cancers (e.g. those detected during Barrett’s screening [see Ch 1] that are treated by curative surgery), the prognosis is generally poor (the 5-year survival rate is about 5% for all patients, but as high as 20% for patients selected for surgical resection). Nevertheless, surgery offers the only hope of cure and, as long as the tumour can be resected with clear margins, this achieves the best palliation. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy has been shown to improve the disease-free interval and possibly survival. Unfortunately, many patients are too old or frail to tolerate this approach. In those unsuitable for surgery by a specialist oesophageal surgeon, palliation of dysphagia can be achieved by placement of an expandable metal stent. Palliative chemotherapy and radiotherapy have limited roles.

Gastric carcinoma

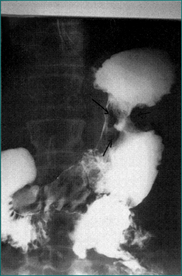

Pathology

Adenocarcinoma accounts for the majority (over 90%) of gastric carcinomas (Fig 17.4). Lymphomas account for most of the remainder. Adenocarcinomas can be further classified histologically into intestinal and diffuse types. The intestinal type is characterised by cohesive neoplastic cells, which form gland-like structures and are frequently polypoid. The diffuse cancers lack cohesion, are usually ulcerative and develop throughout the stomach. Adenocarcinomas are also staged into early and advanced cancers. In early cancers, the depth of invasion is limited to the submucosa; if detected early, gastric cancer is potentially curable with resection.

Aetiology

Chronic atrophic gastritis, which begins as a multifocal process, can progress in those predisposed to intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia. This sequence can ultimately lead to cancer. H. pylori is classified as a class I carcinogen by the World Health Organization; it causes chronic atrophic gastritis and is linked to gastric adenocarcinoma, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma and B-cell lymphoma. Patients with H. pylori infection have a higher risk (three- to sixfold) of developing non-cardia gastric adenocarcinoma. Other risk factors for gastric cancer are listed in Box 17.6. Changes in multiple oncogenes and tumour suppressor genes (e.g. MCC, APC and DDC) have been identified in gastric cancer.

Treatment

Surgery may also afford a means of palliation in patients with gastric outlet obstruction or significant gastrointestinal bleeding. Combination chemotherapy can be used to palliate some non-surgical candidates with advanced gastric cancers. However, the medial survival with combination chemotherapy is only 6–10 months, and is toxic.

Anorexia nervosa

Complications

The medical complications arise from starvation. Hypokalaemia, hypochloraemia and metabolic alkalosis are typical (Table 17.4). Cardiac complications are the most frequent cause of death in these patients. Prolongation of the Q-T interval is thought to predict the onset of serious cardiac arrhythmias. As glucose metabolism and insulin secretion are disturbed, hypoglycaemia is common and potentially lethal. Osteopenia from oestrogen deficiency is common and can lead to debilitating fractures.

Table 17.4 Laboratory findings that may occur in patients with anorexia nervosa

| Investigation | Finding |

|---|---|

| Endocrine investigations | Low gonadotrophin (FSH and LH) levels |

| Low oestrogen and testosterone levels | |

| Sick euthyroid state | |

| Increased cortisol level | |

| Metabolic investigations | Hypokalaemia, metabolic alkalosis |

| Hypocalcaemia, hypomagnesaemia,hypophosphataemia | |

| Hypoglycaemia | |

| Prerenal azotaemia | |

| Haematological investigations | Anaemia, pancytopenia |

| Low plasma protein levels |

Bulimia nervosa

Clinical features

Hypokalaemia and metabolic alkalosis (from vomiting or laxatives) may be present.

Key Points

Attia E., Walsh B.T. Behavioral management for anorexia nervosa. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:500-506.

Bouras E.P., Lange S.M., Scolapio J.R. Rational approach to patients with unintentional weight loss. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:923-929.

Fuccio L., Zagari R.M., Eusebi L.H., et al. Meta-analysis: can Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment reduce the risk for gastric cancer? Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:121-128.

Hernandez J.L., Matorras P., Riancho J.A., et al. Involuntary weight loss without specific symptoms: a clinical prediction score for malignant neoplasm. QJM. 2003;96:649-655.

Katz M.H., Mortenson M.M., Wang H., et al. Diagnosis and management of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: an evidence-based approach. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207(1):106-120.

Lagergren J., Bergstrom R., Lindgren A., et al. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux as a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:825-831.

Madeddu C., Macciò A., Panzone F., et al. Medroxyprogesterone acetate in the management of cancer cachexia. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10(8):1359-1366.

Messing B., Joly F. Guidelines for management of home parenteral support in adult chronic intestinal failure patients. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(2 Suppl. 1):S43-S51.

Penman I.D., Henry E. Advanced esophageal cancer. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2005;15:101-116.

Rolland Y., Kim M.J., Gammack J.K., et al. Office management of weight loss in older persons. Am J Med. 2006;119:1019-1026.

Steinhausen H.C., Weber S. The outcome of bulimia nervosa: findings from one-quarter century of research. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:1331-1341.

Visvanathan R., Chapman I.M. Undernutrition and anorexia in the older person. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2009;38(3):393-409.

Yager J., Andersen A.E. Clinical practice. Anorexia nervosa. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1481-1488.