13 Locomotor system

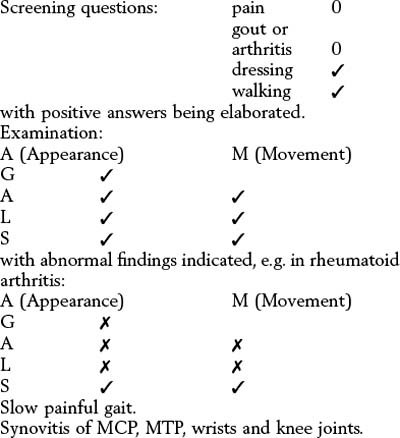

General assessment: the ‘GALS’ locomotor screen

Screening history

If answers to the following four questions are negative, a musculoskeletal disorder is unlikely:

1 Do you have any pain or stiffness in your muscles, joints or back?

2 Have you ever had gout or arthritis?

Positive answers imply the need for a more detailed assessment, as described in this chapter.

Screening examination

Spine

From behind – look for abnormal spinal and paraspinal anatomy and look at the legs.

From behind – look for abnormal spinal and paraspinal anatomy and look at the legs.

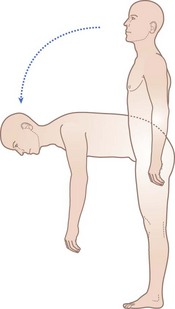

From the side – look for abnormal spinal posture, then ask the patient to bend down and touch his toes (Fig. 13.1).

From the side – look for abnormal spinal posture, then ask the patient to bend down and touch his toes (Fig. 13.1).

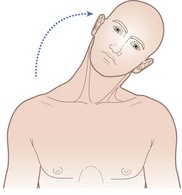

From the front – ask the patient to ‘put your ear on your left then right shoulder’ and watch the neck movements (Fig. 13.2).

From the front – ask the patient to ‘put your ear on your left then right shoulder’ and watch the neck movements (Fig. 13.2).

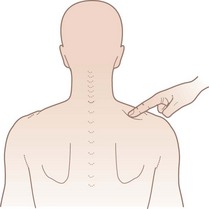

Gently press the mid-point of each supraspinatus muscle to elicit tenderness (Fig. 13.3).

Gently press the mid-point of each supraspinatus muscle to elicit tenderness (Fig. 13.3).

Arms

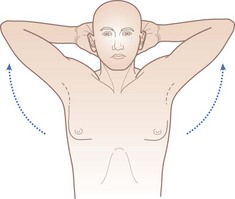

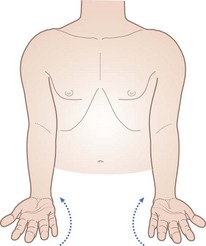

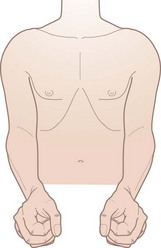

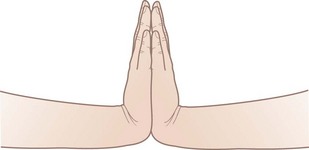

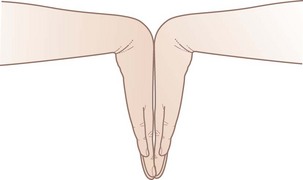

Ask the patient to follow instructions as in Table 13.1 (see Figs 13.4–13.9).

| Instruction | Normal outcome |

|---|---|

| ‘Raise arms out sideways and up above your head’ | 180° elevation through abduction without wincing |

| ‘Touch the middle of your back’ | Touches above T10 with both hands |

| ‘Straighten your elbows right out’ | Elbows extend to 180° or slightly beyond (females) symmetrically |

| ‘Place hands together as if to pray, with elbows right out’ | 90° wrist extension and straight fingers |

| ‘The same with hands back to back’ | 90° wrist flexion |

| ‘Place both hands out in front, palms down, fingers out straight’ | No wrist/finger swelling/deformity, 90° pronation |

| Metacarpophalangeal (MCP) cross-compression | No tenderness |

| ‘Turn hands over’ | 90° supination No palmar swellings, wasting or erythema |

| ‘Make a fist and hide your nails’ | Can hide fingernails |

| ‘Pinch index, middle finger and thumb together’ | Can do |

| Also look for swelling between the heads of the metacarpals and gently squeeze across the MCP joints to elicit tenderness | Tenderness may be elicited |

Legs

With the patient still standing:

Examine the lower limbs for swelling, deformities or limb shortening. Normal: no knee deformity, anterior or popliteal swelling, no muscle-wasting, no hindfoot swelling or deformity.

Examine the lower limbs for swelling, deformities or limb shortening. Normal: no knee deformity, anterior or popliteal swelling, no muscle-wasting, no hindfoot swelling or deformity.

Then, with the patient lying on a couch, continue the examination following the instructions in Table 13.2 (see Figs 13.10–13.14).

Then, with the patient lying on a couch, continue the examination following the instructions in Table 13.2 (see Figs 13.10–13.14).

| Instruction | Normal outcome |

|---|---|

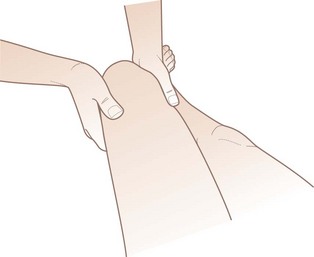

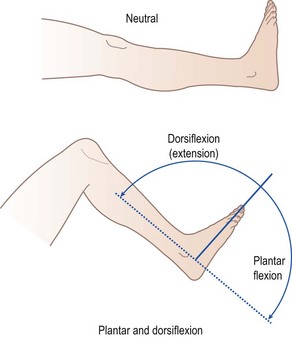

| Flex hip and knee, holding knee | No bony crepitus, 140° knee flexion |

| Passively rotate hips | 90° total pain-free rotation |

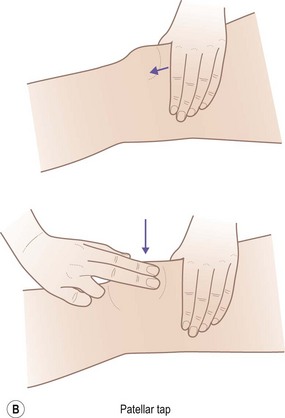

| Bulge test/patellar tap | No detectable fluid |

| Palpate popliteal fossa | No swelling |

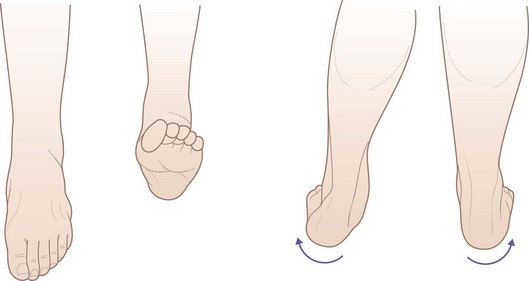

| Inspect feet | No deformity, callosities or forefoot widening (daylight sign) |

| Test subtalar and ankle movement | Pain-free calcaneal mobility at subtalar joint, dorsiflexion beyond plantigrade and 30° plantarflexion |

Specific locomotor history

Pain may be referred or radiate from an affected joint:

Neck pain may radiate through the occiput to the vertex or to the shoulder and down the arm, with paraesthesiae if there is nerve-root impingement.

Neck pain may radiate through the occiput to the vertex or to the shoulder and down the arm, with paraesthesiae if there is nerve-root impingement.

Shoulder joint pain may radiate to the elbow and below.

Shoulder joint pain may radiate to the elbow and below.

Thoracic spine nerve root pain may radiate around the chest and mimic cardiac pain.

Thoracic spine nerve root pain may radiate around the chest and mimic cardiac pain.

Lumbar spinal root pain may radiate through the buttock and leg to the knee and below, with paraesthesiae in the foot with a large disc prolapse – this is called ‘sciatica’.

Lumbar spinal root pain may radiate through the buttock and leg to the knee and below, with paraesthesiae in the foot with a large disc prolapse – this is called ‘sciatica’.

Joint disease

Distribution of joint disease

The pattern of joint involvement is important. Common patterns are: monoarticular (single joint), pauciarticular (up to four joints), polyarticular (many joints) and axial (spinal involvement). Symmetry is useful in distinguishing various inflammatory arthropathies. There are only a few causes of an exactly symmetrical arthropathy (Box 13.1). Other conditions have such a classic history that this is diagnostic. For example, acute inflammation in the first metatarsophalangeal joint (hallux) suggests a diagnosis of gout (Box 13.2). The pain and stiffness of the shoulder and hip girdles in polymyalgia rheumatica is also typical (Box 13.3). The pattern of the spondyloarthropathies can also be diagnostic with inflammatory sacroiliac and spinal pain and stiffness, lower limb arthritis, Achilles tendonitis and plantar fasciitis.

Box 13.1 Importance of distribution of joint involvement in differential diagnosis of pauci- or polyarthritis

Box 13.2 Acute gout

A 48-year-old publican presented with sudden severe pain and swelling of his left big toe. He was unable to weightbear or wear a shoe, and said that he could not even bear the weight of his bed clothes on the toe at night. His past history included hypertension, for which he was taking a thiazide diuretic, and his alcohol intake was excessive. On examination, he had tophi on the ears (Fig. 13.15) and the left first metatarsophalangeal joint was red, hot, swollen and exquisitely painful to touch. Aspiration of the joint revealed urate crystals.

Flitting or migratory joint pains

The other features in the history that should be brought out are best considered under the differential diagnosis of polyarthritis (Box 13.4). Many arthropathies may have a monoarticular presentation.

Inflammatory connective tissue diseases

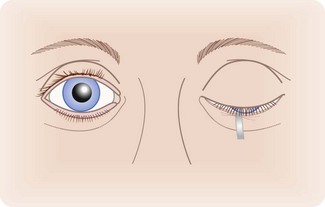

The autoimmune rheumatic disorders, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Sjögren’s syndrome, inflammatory myopathies, systemic sclerosis and the vasculitides, are multisystem disorders. A careful systems enquiry is essential if this diagnosis is suspected. Associated features of these conditions include systemic symptoms such as weight loss, malaise or fevers, and rash, especially if the latter is photosensitive or vasculitic (Fig. 13.16). Alopecia, oral and genital ulceration, Raynaud’s phenomenon and symptoms of neurological, cardiac, pulmonary and gastrointestinal involvement may occur. Dry eyes and dry mouth (sicca symptoms) are common and can be documented with Schirmer’s test (Fig. 13.17). Renal disease is a serious complication of the autoimmune rheumatic disorders, especially in SLE and the systemic vasculitides. Clinical assessment should always include measuring blood pressure and dip-testing the urine for blood and protein, and microscopy of the urine sediment for casts or dysmorphic red cells if this is positive. Ear, nose and throat involvement with sinusitis, facial pain and deafness is common in Wegener’s granulomatosis and Churg–Strauss syndrome. A history of arterial and venous thromboses or miscarriages, especially in the context of livedo reticularis, should raise the suspicion of the antiphospholipid syndrome.

Soft tissue symptoms

Soft tissue problems are common and usually consist of pain, a dull ache, tenderness or swelling. In the elderly these symptoms often appear spontaneously, but in younger people there is usually a history of injury or overuse, through either occupation (e.g. tenosynovitis of the long flexor tendons of the hand) or sport (e.g. Achilles tendinitis). It is important to define the exact site of the symptoms, and the factors that either make them worse or induce relief. The localization of symptoms to specific soft tissue structures can be confirmed by careful examination (Box 13.5). The possible soft tissues involved are joint, tendon, ligament, bursa and muscle.

Examination: general principles

Observe the patient entering the room (Box 13.6). Abnormalities of gait and posture may provide clues that can be pursued in history taking. Observation of any difficulty in undressing and getting onto the examination couch will further help in assessment. The patient must always be asked to stand and walk, even when it is obvious that this may be difficult. Note how much help the patient requires from others or from sticks, crutches, etc. The musculoskeletal system includes the muscles, bones, joints and soft tissue structures such as tendons and ligaments. Remember that although muscle-wasting may be due to primary muscle disease (e.g. polymyositis), it is more commonly secondary to disuse, perhaps because of a painful joint, or to neuropathy due to nerve-root compression or peripheral neuropathy (Fig. 13.18). Examination of the muscles is discussed further in Chapter 14.

The bones

The examination of the bones should always be directed by information obtained from the history.

Inspection

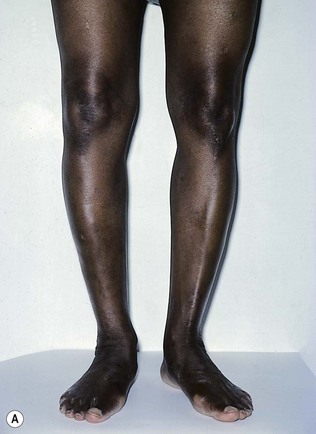

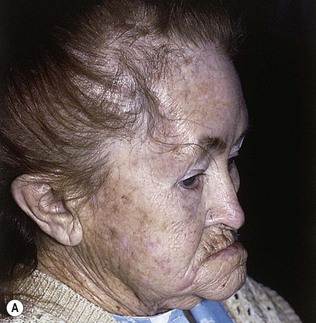

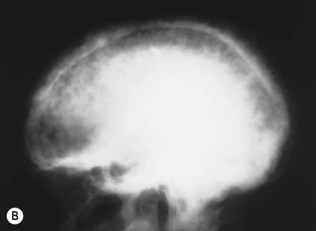

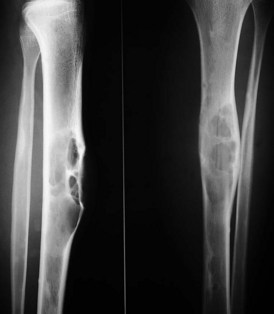

Look for any alterations in shape or outline and measure any shortening. In Paget’s disease (osteitis deformans), bowing of the long bones, particularly the tibia (Fig. 13.19) and femur, is associated with bony enlargement and, usually, increased local temperature. The skull is also commonly involved, but this may not be apparent until the disease is advanced. Early involvement of the skull bones can be detected on X-rays (Fig. 13.20). Alterations in the shape of bones also occur in rickets as a result of epiphyseal enlargement. Deformity of the chest in rickets is due to osteochondral enlargement (rickety rosary).

Fractures

Fractures are common and may involve any bone. They are painful, distressing for the patient and expensive for the community (Box 13.7). Fractures in healthy bones commonly involve the long bones and are usually due to trauma. Fractures of the wrists, hips and vertebrae are more frequently complications of bone disease, such as osteoporosis. Multiple rib fractures, caused by falls, may be found in heavy alcohol users, but may only be seen as healed lesions on chest X-ray. Fractures occur without apparent trauma when a bone is weakened by disease, especially with metastatic malignant deposits in bone (pathological fractures). Traumatic fractures invariably present with local pain, swelling and loss of function, but pathological fractures may be relatively silent. The history will reveal the circumstances of the trauma, whether accidental or due to physical abuse, and should be carefully documented, if necessary with diagrams or digital photographs of the clinical findings. If clinical photographs are taken, prior written consent is needed.

The joints

Inspection

The detection of joint inflammation is a crucial clinical skill. Inflammation is often associated with redness of the joint, and with tenderness and warmth. Look also for swelling or deformity of the joint. The overall pattern of joint involvement should be recorded. Note whether the distribution is symmetrical, as is usual in rheumatoid arthritis (Fig. 13.21), or asymmetrical, as in psoriatic arthropathy or gout (Fig. 13.22). The seronegative spondyloarthropathies (Fig. 13.23) tend to involve predominantly the joints of the lower limb.

Palpation

On palpation of a joint, check first for tenderness. Then determine whether the swelling is due to bony enlargement or osteophytes (e.g. Heberden’s nodes, Fig. 13.24), thickening of synovial tissues, such as occurs in inflammatory arthritis, or effusion into the joint space. Joint effusions usually have a characteristically smooth outline and fluctuation is usually easily demonstrable. Tenderness and enlargement of the ends of long bones, particularly the radius, ulna and tibia, can occur in hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy: a chest X-ray is essential. Gross disorganization of a joint – nearly always the foot and ankle joints – associated with an absence of deep pain and position sense occurs in neuropathic (Charcot) joints. Charcot joints probably arise from recurrent painless injury and overstretching, and are a feature of severe chronic sensorimotor neuropathy.

Joint tenderness may be graded depending on the patient’s reaction to firm pressure of the joint between finger and thumb (Box 13.8). Grade 4 tenderness occurs only in septic arthritis, crystal arthritis and rheumatic fever. In gout, the skin overlying the affected joint is dry, whereas in septic arthritis or rheumatic fever, it is usually moist.

Extra-articular features of joint disease

Some of the extra-articular features of joint disease are listed in Box 13.9.

Subcutaneous nodules

Subcutaneous nodules are associated with several conditions (Box 13.10). If gout is suspected, inspect the helix of the ear for tophi caused by the subcutaneous deposition of urate, which may also be found overlying joints or in the finger pulps (see Figs 13.15 and 13.22). Subcutaneous nodules in rheumatoid arthritis are firm and non-tender; they may be detected by running the examining thumb from the point of the elbow down the proximal portion of the ulna (Fig. 13.25). They can also be found at other pressure and frictional sites, such as bony prominences, including the sacrum. If an olecranon bursa swelling is found, feel also in its wall, as rheumatoid nodules, tophi or, occasionally, xanthomata may be found within the swelling. Subcutaneous nodules are not specific to rheumatoid arthritis and may occur in patients with SLE, systemic sclerosis and rheumatic fever.

Cutaneous vasculitic lesions

These may be seen in rheumatoid arthritis, SLE, Sjögren’s syndrome and the systemic vasculitides. They may be small, punched-out necrotic lesions, palpable purpura or vasculitic ulcers, especially on the lower limbs. Small vessel involvement is typically seen at the nail fold (cutaneous infarct; Fig. 13.26), but also occurs at pressure sites. Splinter haemorrhages, the classic feature of bacterial endocarditis, may also be a feature of vasculitis and the antiphospholipid syndrome.

Local oedema

Local oedema is sometimes seen over inflamed joints (Fig. 13.27), but other causes of oedema must be excluded. Pitting leg oedema may indicate cardiac failure, pericardial effusion or nephrotic syndrome, which can complicate rheumatoid arthritis and SLE.

Examination of individual joints

The spine

General examination of the vertebral column

Palpation

The neutral position of the spine is an upright stance with head erect and chin drawn in. Note any curvature of the spinal column, whether as a whole or of part of it. Abnormal curvature may be in an anterior, posterior or lateral direction (Fig. 13.28). Anterior curvature (convex forward) is termed lordosis. There are natural lordotic curves in the cervical and lumbar regions. Posterior curvature (convex backward) is termed kyphosis. The thoracic spine usually exhibits a slight smooth kyphosis, which increases in the elderly and especially in osteoporosis. It must be distinguished from a localized angular deformity (gibbus; Fig. 13.29) caused by a fracture, by Pott’s disease (spinal tuberculosis; Fig. 13.30) or by a metastatic malignant deposit.

Figure 13.30 X-ray tuberculous discitis. This shows the underlying deformity shown in Figure 13.29. There is tuberculous infection of the intervertebral disc, causing the spinal deformity.

Lateral curvature is termed scoliosis (see Fig. 13.28) and may be towards either side. It is always accompanied by rotation of the bodies of the vertebrae in such a way that the posterior spinous processes come to point towards the concavity of the curve. The curvature is always greater than appears from inspection of the posterior spinous processes. In scoliosis due to muscle spasm (e.g. with lumbosacral disc protrusion syndromes), the spinal curvature and rotational deformity decrease in flexion. When scoliosis is caused by inequality of leg length, it disappears on sitting, because the buttocks then become level. Scoliosis secondary to skeletal anomalies shows in spinal flexion as a ‘rib hump’ due to the rotation. Kyphosis and scoliosis are often combined, particularly when the cause is an idiopathic spinal curvature, beginning in adolescence.

The cervical spine

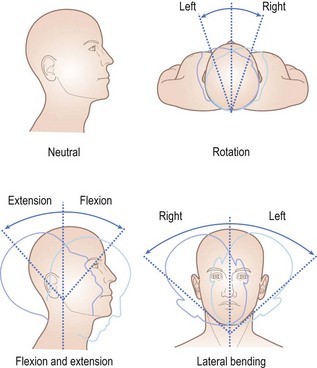

The following movements should be tested (Fig. 13.31):

Rotation (ask the patient to look over one then the other shoulder).

Rotation (ask the patient to look over one then the other shoulder).

Flexion (ask the patient to touch chin to chest).

Flexion (ask the patient to touch chin to chest).

Extension (ask the patient to look up to the ceiling).

Extension (ask the patient to look up to the ceiling).

Lateral bending (ask the patient to bend the neck sideways and to try to touch the shoulder with the ear without raising the shoulder).

Lateral bending (ask the patient to bend the neck sideways and to try to touch the shoulder with the ear without raising the shoulder).

In patients with cervical injury, never try to elicit range of motion of the neck. Instead, splint the neck, take a history, look for abnormality of posture (usually in rotation) and check neurological function in the limbs, including both arms and both legs. Imaging the neck in the lateral (Fig. 13.32) and anteroposterior planes, without moving the neck, is essential and may be with plain radiography or, in trauma patients, with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to assess injury to the cord. Only if imaging is normal should neck movements be examined.

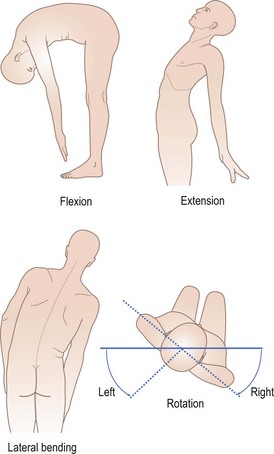

The thoracic and lumbar spine

The main movement at the thoracic spine is rotation, whereas the lumbar spine can flex, extend, and bend laterally. The following movements should be tested (Fig. 13.33):

Flexion (ask the patient to try to touch his toes, without bending at the knees).

Flexion (ask the patient to try to touch his toes, without bending at the knees).

Extension (ask the patient to bend backwards).

Extension (ask the patient to bend backwards).

Lateral bending (ask the patient to run the hand down the side of the thigh as far as possible.

Lateral bending (ask the patient to run the hand down the side of the thigh as far as possible.

Thoracic rotation (ask the seated patient, with arms crossed, to twist round to the left and right as far as possible).

Thoracic rotation (ask the seated patient, with arms crossed, to twist round to the left and right as far as possible).

In flexion, the normal lumbar lordosis should be abolished. The extent of lumbar flexion can be assessed more accurately by marking a vertical 10-cm line on the skin overlying the lumbar spinous processes and the sacral dimples and measuring the increase in the line length on flexion (modified Schober’s test): this should normally be 5 cm or more. Painful restriction of spinal movement is an important sign of cervical and lumbar spondylosis, but may also be found in vertebral disc disease or other mechanical disorders of the back or neck. A useful clinical aphorism is that a rigid lumbar spine should always be investigated for serious pathology, such as infection (e.g. staphylococcal or tuberculous discitis), malignancy or inflammation (e.g. ankylosing spondylitis). Spinal movements may be virtually absent in ankylosing spondylitis (Fig. 13.34), but in the early stages of this condition, lateral flexion of the lumbar spine is typically affected first. In mechanical or osteoarthritic back problems, flexion and extension are reduced more than lateral movements. In prolapsed intervertebral disc lesions, sustained gentle lumbar extension may reproduce the low back pain and sciatic radiation.

The sacroiliac joints

Direct pressure over each sacroiliac joint.

Direct pressure over each sacroiliac joint.

Firm pressure with the side of the hand over the sacrum.

Firm pressure with the side of the hand over the sacrum.

Inward pressure over both iliac bones with the patient lying on one side, in an attempt to distort the pelvis.

Inward pressure over both iliac bones with the patient lying on one side, in an attempt to distort the pelvis.

Flex the hip to 90° and exert firm pressure at the knee through the femoral shaft (this should only be done if the hip and knee are not painful).

Flex the hip to 90° and exert firm pressure at the knee through the femoral shaft (this should only be done if the hip and knee are not painful).

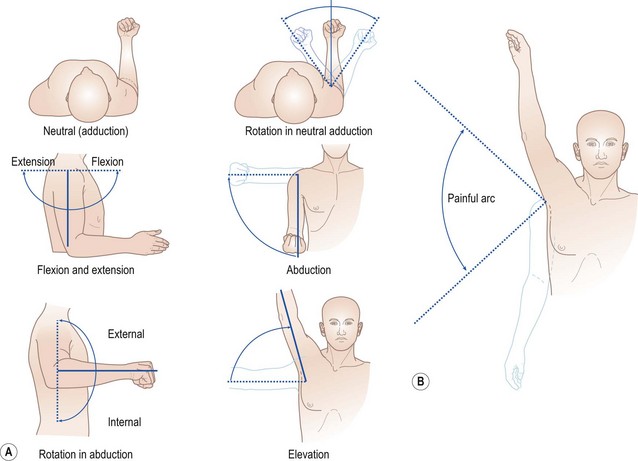

The shoulder

The neutral position is with the arm to the side, elbow flexed to 90° and forearm pointing forwards. Because the scapula is mobile, true shoulder (glenohumeral) movement can be assessed only when the examiner anchors the scapula between finger and thumb on the posterior chest wall. The following movements should be tested (Fig. 13.35):

Note any pain during the range of movement. In supraspinatus tendinitis, a full passive range of movement is found but there is a painful arc on abduction, with pain exacerbated on resisted abduction (see Fig. 13.35). Other tendon involvement should also be defined by pain on resisted action.

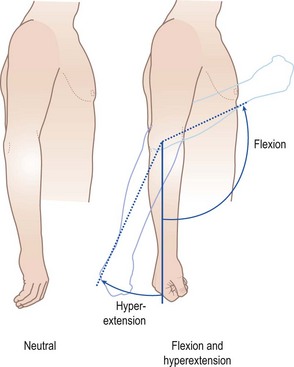

The elbow

The neutral position is with the forearm in extension. The following movements should be tested (Fig. 13.36):

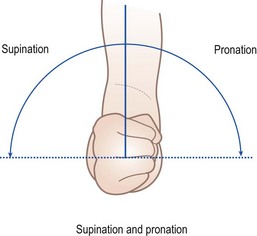

The forearm

The neutral position is with the arm by the side, elbow flexed to 90° and thumb uppermost. The following movements should be tested (Fig. 13.37):

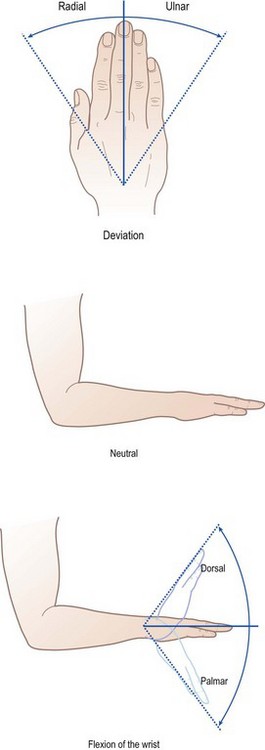

The wrist

The neutral position is with the hand in line with the forearm, and palm down. The following movements should be tested (Fig. 13.38):

Even minor limitation of wrist flexion or extension can be detected by comparing movement in both wrists (Fig. 13.39). Limitation of the wrist joints is usually due to inflammatory arthritis. Primary osteoarthritis of the wrist is rare, but secondary degenerative change is common.

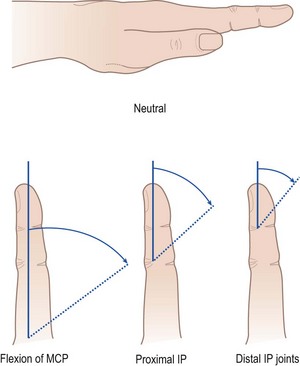

The fingers

When identifying fingers, use the names thumb, index, middle, ring and little. Numbering tends to lead to confusion. The neutral position is with the fingers in extension. Test flexion at the metacarpophalangeal (MCP), proximal interphalangeal (PIP) and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints (Fig. 13.40).

The thumb (carpometacarpal joint)

The neutral position is with the thumb alongside the forefinger, and extended. The following movements should be tested (Fig. 13.41):

The hand

Deformities in joint disease

Examination of the individual joints of the hand may be less informative than inspection of the hand as a whole (Fig. 13.42). The combination of Heberden’s nodes and thumb carpometacarpal arthritis occurs in osteoarthritis (see Fig. 13.24). Pain and subluxation of the carpometacarpal joint is a typical feature of primary nodal osteoarthritis, leading to a ‘square hand’ appearance on making a fist.

A variety of patterns of deformity are characteristic of longstanding rheumatoid arthritis. For example, metacarpophalangeal joint subluxation, ulnar deviation of the fingers at the metacarpophalangeal joints, ‘swan neck’ (Fig. 13.43), and ‘boutonnière’ deformities (flexed proximal and hyperextended distal interphalangeal joints) of the fingers are typical in advanced disease. This is due to the head of the phalanx sliding dorsally between the lateral slips of the extensor tendon, the middle slip having been damaged. In psoriatic arthritis, terminal interphalangeal joint swelling may occur, with psoriatic pitting and ridging of the nail (onychopathy) on that digit.

Deformities due to neuropathy

The hand may adopt a posture typical of a nerve lesion (see Ch. 14). Slight hyperextension of the medial metacarpophalangeal joints with slight flexion of the interphalangeal joints is the ‘ulnar claw hand’ of an ulnar nerve lesion. There is wasting of the small muscles of the hypothenar eminence, with loss of sensation of the palmar and dorsal aspects of the little finger and of the ulnar half of the ring finger. In a median nerve lesion, the thenar eminence (abductor pollicis brevis) will be flattened (see Fig. 13.18) and sensory impairment will be found on the palmar surfaces of the thumb, index, middle and radial half of the ring fingers. Remember that carpal tunnel syndrome may be a presenting feature of wrist inflammation.

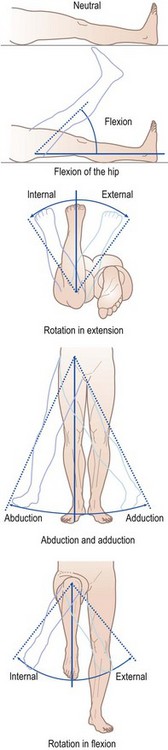

The hip

The neutral position is with the hip in extension and the patella pointing forwards. Ensure the pelvis does not tilt by placing one hand over it while examining the hip with the other. Look for scars and wasting of the gluteal and the thigh muscles. The hip joint is too deeply placed to be accessible to palpation. The following movements should be tested (Fig. 13.44):

Flexion: measured with knee bent. Opposite thigh must remain in neutral position. Flex the knee as the hip flexes.

Flexion: measured with knee bent. Opposite thigh must remain in neutral position. Flex the knee as the hip flexes.

Abduction: measured from a line that forms an angle of 90° with a line joining the anterior superior iliac spines.

Abduction: measured from a line that forms an angle of 90° with a line joining the anterior superior iliac spines.

Adduction (measured in the same manner).

Adduction (measured in the same manner).

Extension: attempt to extend the hip with the patient lying in the lateral or prone position.

Extension: attempt to extend the hip with the patient lying in the lateral or prone position.

Additional examination of the hip joint

Test for flexion deformity. With one hand flat between the lumbar spine and the couch, flex the normal hip fully to the point of abolishing the lumbar lordosis. The spine will come down onto the hand, pressing it onto the couch. If there is a flexion deformity on the opposite side, the leg on that side will move into a flexed position (Thomas’ test).

Test for flexion deformity. With one hand flat between the lumbar spine and the couch, flex the normal hip fully to the point of abolishing the lumbar lordosis. The spine will come down onto the hand, pressing it onto the couch. If there is a flexion deformity on the opposite side, the leg on that side will move into a flexed position (Thomas’ test).

Trendelenburg test. Observe the patient from behind and ask him to stand on one leg. In health, the pelvis tilts upwards on the side with the leg raised. When the weightbearing hip is abnormal, owing to pain or subluxation, the pelvis sags downwards due to weakness of the hip abductors on the affected side.

Trendelenburg test. Observe the patient from behind and ask him to stand on one leg. In health, the pelvis tilts upwards on the side with the leg raised. When the weightbearing hip is abnormal, owing to pain or subluxation, the pelvis sags downwards due to weakness of the hip abductors on the affected side.

Measurement of ‘true’ and ‘apparent’ shortening. The length of the legs is measured from the anterior superior iliac spine to the medial malleolus on the same side. Any difference is termed ‘true’ shortening and may result from disease of either the hip joint or the neck of the femur on the shorter side. ‘Apparent’ shortening is due to tilting of the pelvis and can be measured by comparing the lengths of the two legs, measured from the umbilicus, provided there is no true shortening of one leg. Apparent shortening is usually due to an abduction deformity of the hip. Femoral or tibial shortening may be demonstrated with the patient lying on a couch and looking across both knees held equally flexed.

Measurement of ‘true’ and ‘apparent’ shortening. The length of the legs is measured from the anterior superior iliac spine to the medial malleolus on the same side. Any difference is termed ‘true’ shortening and may result from disease of either the hip joint or the neck of the femur on the shorter side. ‘Apparent’ shortening is due to tilting of the pelvis and can be measured by comparing the lengths of the two legs, measured from the umbilicus, provided there is no true shortening of one leg. Apparent shortening is usually due to an abduction deformity of the hip. Femoral or tibial shortening may be demonstrated with the patient lying on a couch and looking across both knees held equally flexed.

The knee

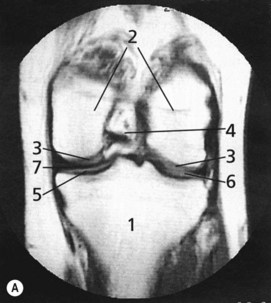

MRI scans of the normal knee are illustrated in Figure 13.45. The neutral position is complete extension. Observe any valgus (lateral angulation of the tibia) or varus (medial angulation) deformity on the couch and on standing. Look for muscle wasting. The quadriceps, especially its medial part near the knee, wastes rapidly in knee joint disease. Swelling may be obvious, particularly if it distends the suprapatellar pouch. Check the apparent height of the patella and watch to see if it deviates to one side in flexion or extension of the knee. Feel for tenderness at the joint margins, not forgetting the patellofemoral joint. Palpate the ligaments, remembering that the medial collateral ligament is attached 8 cm below the joint line. Measure the girth of the thigh muscles 10 cm above the upper pole of the patella.

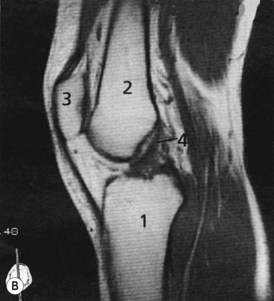

Joint swelling

The movements of the knee are flexion and extension (Fig. 13.46). Loss of flexion can be documented by loss of the angle of flexion or loss of heel-to-buttock distance, either in the crouching position or on the couch. Loss of extension is detected by inability to get the back of the knee onto the flat examining couch. Hyperextension must be sought by lifting the foot with the knee extended and comparing with the normal side. Lack of full extension by comparison with the normal constitutes fixed flexion deformity. Loose bodies in the joint cause crepitus, interruption of movement (locking) and pain and effusion (Fig. 13.47).

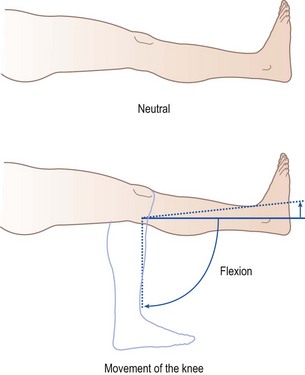

The ankle

The foot

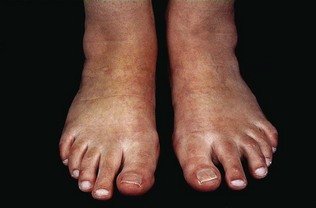

Callosities are areas of hard skin under points of abnormal pressure. The most common site is beneath the metatarsal heads because loss of the normal soft tissue pad allows abnormal loading. There may be abnormal spread of two adjacent toes (daylight sign: Fig. 13.49) on weightbearing if there is synovitis between the metatarsal heads. Check for lateral deviation of the big toe (hallux valgus), usually associated with abnormal swelling at its base (a bunion). There may be deformities affecting any or all toes, with abnormal curvature (claw toes), fixed flexion of the terminal joint (hammer toes) or overriding.

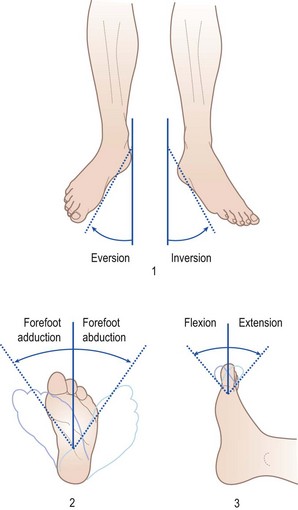

The following movements should be tested (Fig. 13.50):

Subtalar inversion and eversion: cup the heel in the hands and move it in relation to the tibia without any up and down movement; this eliminates movement at the ankle or mid-tarsal joints.

Subtalar inversion and eversion: cup the heel in the hands and move it in relation to the tibia without any up and down movement; this eliminates movement at the ankle or mid-tarsal joints.

Mid-tarsal inversion/eversion and adduction/abduction: hold the os calcis in the neutral position in one hand and grasp and rotate the forefoot in the other.

Mid-tarsal inversion/eversion and adduction/abduction: hold the os calcis in the neutral position in one hand and grasp and rotate the forefoot in the other.

The gait

Abnormalities of gait are usually due either to joint problems in the legs or to neurological disorder, although alcohol intoxication or malingering may occasionally cause difficulty. A full examination of the legs and feet should reveal any local cause, which may range from a painful corn to osteoarthritis of the hip. Abnormalities due to neurological disorders are described in Chapter 14.

Hypermobility

There is a wide variation in the range of normal joint movement, associated with age, sex and race. Excessive laxity or hypermobility of the joints (Fig. 13.51) can be defined in about 10% of healthy subjects and is frequently familial. It is also a feature of two inherited connective tissue disorders: Marfan’s syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Repeated trauma, haemarthrosis or dislocation may produce permanent joint damage.

Investigations in rheumatic diseases

Tests in support of inflammatory disease

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). This is a useful screening test, although it has poor specificity, being affected by the levels of haemoglobin, globulins and fibrinogen. Higher mean values are seen in healthy elderly individuals.

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). This is a useful screening test, although it has poor specificity, being affected by the levels of haemoglobin, globulins and fibrinogen. Higher mean values are seen in healthy elderly individuals.

C-reactive protein (CRP). This is a more specific indicator of inflammation and is a good marker of the acute-phase response. A high ESR with a normal CRP is a useful pointer towards autoimmune rheumatic diseases, especially SLE.

C-reactive protein (CRP). This is a more specific indicator of inflammation and is a good marker of the acute-phase response. A high ESR with a normal CRP is a useful pointer towards autoimmune rheumatic diseases, especially SLE.

Plasma viscosity. This is a more specific measure of the acute-phase response than ESR, but may not be as widely available.

Plasma viscosity. This is a more specific measure of the acute-phase response than ESR, but may not be as widely available.

Anaemia and thrombocytosis. Anaemia of chronic disease and a high platelet count often occur in inflammatory disease but are non-specific. Other abnormalities on blood count, such as neutropenia, thrombocytopenia and lymphopenia, are common in SLE.

Anaemia and thrombocytosis. Anaemia of chronic disease and a high platelet count often occur in inflammatory disease but are non-specific. Other abnormalities on blood count, such as neutropenia, thrombocytopenia and lymphopenia, are common in SLE.

Serum complement. Low levels of serum complement reflect activation due to immune complex deposition; this may be a marker of disease activity in autoimmune diseases such as SLE. Hereditary complement deficiencies are also associated with SLE.

Serum complement. Low levels of serum complement reflect activation due to immune complex deposition; this may be a marker of disease activity in autoimmune diseases such as SLE. Hereditary complement deficiencies are also associated with SLE.

Muscle enzymes. Elevated creatine kinase levels occur in most patients with inflammatory myopathy.

Muscle enzymes. Elevated creatine kinase levels occur in most patients with inflammatory myopathy.

Diagnostic tests

Diagnostic tests differentiate between specific diseases and are relatively specific investigations.

Antibody tests to extractable nuclear antigens (ENA)

Anti-Ro (SSA) and anti-La (SSB), typically in Sjögren’s syndrome. Also seen in SLE, where they are associated with photosensitivity, and the neonatal lupus syndrome, which may result in congenital heart block and neonatal rashes.

Anti-Ro (SSA) and anti-La (SSB), typically in Sjögren’s syndrome. Also seen in SLE, where they are associated with photosensitivity, and the neonatal lupus syndrome, which may result in congenital heart block and neonatal rashes.

Anti-Sm in 5-10% of patients with SLE: a very specific marker if present.

Anti-Sm in 5-10% of patients with SLE: a very specific marker if present.

Anti-RNP (ribonucleoprotein) in some cases of SLE. Also picks out a group of patients who have clinical features of other autoimmune rheumatic disorders and who are therefore often diagnosed as mixed connective-tissue disease (MCTD). The test can be considered a marker for the combination of clinical features, but the major clinical component of the condition will define management.

Anti-RNP (ribonucleoprotein) in some cases of SLE. Also picks out a group of patients who have clinical features of other autoimmune rheumatic disorders and who are therefore often diagnosed as mixed connective-tissue disease (MCTD). The test can be considered a marker for the combination of clinical features, but the major clinical component of the condition will define management.

Anticentromere antibody is found in limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis or ‘CREST syndrome’ (calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, oesophageal symptoms, sclerodactyly and telangiectasiae).

Anticentromere antibody is found in limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis or ‘CREST syndrome’ (calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, oesophageal symptoms, sclerodactyly and telangiectasiae).

Anti-Scl 70 (DNA topoisomerase I) and anti-RNA polymerase are found in scleroderma and are associated with severe disease.

Anti-Scl 70 (DNA topoisomerase I) and anti-RNA polymerase are found in scleroderma and are associated with severe disease.

Other diagnostic antibody tests include the following:

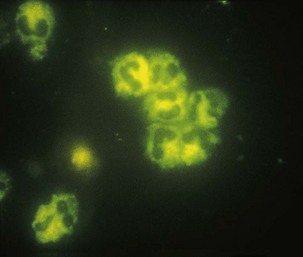

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies are a marker for vasculitic conditions. Two immunofluorescence staining patterns occur:

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies are a marker for vasculitic conditions. Two immunofluorescence staining patterns occur:

Antiphospholipid antibodies include anticardiolipin antibodies, β2 glycoprotein 1 antibodies and the lupus anticoagulant tests and are associated with the antiphospholipid syndrome, characterized by arterial and venous thromboses and, in women, recurrent pregnancy loss and pregnancy morbidity. A false positive VDRL (see Ch. 21) may also be found in these patients.

Antiphospholipid antibodies include anticardiolipin antibodies, β2 glycoprotein 1 antibodies and the lupus anticoagulant tests and are associated with the antiphospholipid syndrome, characterized by arterial and venous thromboses and, in women, recurrent pregnancy loss and pregnancy morbidity. A false positive VDRL (see Ch. 21) may also be found in these patients.

Anti-Jo 1 (histidyl t-RNA synthetase) is a marker for the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies such as dermatomyositis and polymyositis, especially when complicated by interstitial lung disease.

Anti-Jo 1 (histidyl t-RNA synthetase) is a marker for the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies such as dermatomyositis and polymyositis, especially when complicated by interstitial lung disease.

Cryoglobulins are detected by clotting whole blood at 37°C and cooling the serum to 4°C and looking for a precipitate which is usually an IgM rheumatoid factor. Cryoglobulins are associated with vasculitis, infections such as hepatitis C and myeloproliferative disorders.

Cryoglobulins are detected by clotting whole blood at 37°C and cooling the serum to 4°C and looking for a precipitate which is usually an IgM rheumatoid factor. Cryoglobulins are associated with vasculitis, infections such as hepatitis C and myeloproliferative disorders.

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typing: the association of tissue antigen HLA-B27 with ankylosing spondylitis remains the strongest association in medicine. Although about 95% of ankylosing spondylitis patients in the UK possess the B27 antigen, it is also found in 8% of the normal population. Ankylosing spondylitis, therefore, remains a clinical diagnosis, supported by typical radiographic findings. However, in early disease, in children with peripheral arthritis or where the clinical findings are atypical, HLA-B27 typing may provide supportive diagnostic value.

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typing: the association of tissue antigen HLA-B27 with ankylosing spondylitis remains the strongest association in medicine. Although about 95% of ankylosing spondylitis patients in the UK possess the B27 antigen, it is also found in 8% of the normal population. Ankylosing spondylitis, therefore, remains a clinical diagnosis, supported by typical radiographic findings. However, in early disease, in children with peripheral arthritis or where the clinical findings are atypical, HLA-B27 typing may provide supportive diagnostic value.

Antistreptolysin-O (ASO) test: the presence in the serum of this antibody in a titre greater than 1/200, rising on repeat testing after about 2 weeks, indicates a recent haemolytic streptococcal infection.

Antistreptolysin-O (ASO) test: the presence in the serum of this antibody in a titre greater than 1/200, rising on repeat testing after about 2 weeks, indicates a recent haemolytic streptococcal infection.

Viral titres. Certain viruses, notably parvovirus and Coxsackie virus, may cause transient musculoskeletal symptoms which may be mistaken for systemic diseases. Rising viral titres may be useful in the differential diagnosis.

Viral titres. Certain viruses, notably parvovirus and Coxsackie virus, may cause transient musculoskeletal symptoms which may be mistaken for systemic diseases. Rising viral titres may be useful in the differential diagnosis.

Synovial fluid examination

An injured joint can also be aspirated (Box 13.11). The joint swollen after injury may reveal clear pink fluid suggesting a meniscal lesion, or show frank blood. The latter is usually indicative of a torn anterior cruciate ligament. If blood is aspirated, look at its surface for fat globules. This is derived from the marrow and confirms an intra-articular fracture. Synovial fluid examination is diagnostic in two conditions – bacterial infections and crystal synovitis – and every effort should be made to obtain fluid when either of these is suspected. Polarized light microscopy can differentiate between the crystals of urate in gout and those of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate in pseudogout. Outside these conditions, synovial fluid examination is unlikely to be diagnostic. Frank blood may point to trauma, haemophilia or villonodular synovitis, whereas inflammatory (as opposed to degenerative) arthritis is suggested by opaque fluid of low viscosity, with a total white cell count >1000/ml, neutrophils >50%, protein content >35 g/l and the presence of a firm clot. Culture of this fluid may produce a bacterial growth, usually of staphylococci, but occasionally Mycobacterium tuberculosis or other organisms.

Biopsies useful in differential diagnosis

The following biopsies may be useful in the differential diagnosis of rheumatic diseases:

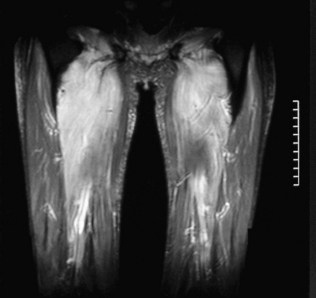

Muscle biopsy should be considered in patients with inflammatory myopathies such as dermatomyositis, polymyositis and inclusion body myositis. Electromyography may show typical features of myopathy and biopsy may be guided by MRI of muscles (Fig 13.53).

Muscle biopsy should be considered in patients with inflammatory myopathies such as dermatomyositis, polymyositis and inclusion body myositis. Electromyography may show typical features of myopathy and biopsy may be guided by MRI of muscles (Fig 13.53).

Rectal biopsy can be useful in the diagnosis of amyloidosis secondary to chronic inflammatory disease, but renal biopsy may still be necessary if the cause of renal impairment is not clear.

Rectal biopsy can be useful in the diagnosis of amyloidosis secondary to chronic inflammatory disease, but renal biopsy may still be necessary if the cause of renal impairment is not clear.

Renal biopsy is essential in the vasculitides or SLE where active glomerulonephritis is suspected. Vasculitis may also be confirmed on renal biopsy but, in general, tissues found to be abnormal on clinical examination or by further investigation (e.g. skin, muscle, sural nerve or liver) should be considered first for diagnostic biopsy in undifferentiated systemic vasculitis.

Renal biopsy is essential in the vasculitides or SLE where active glomerulonephritis is suspected. Vasculitis may also be confirmed on renal biopsy but, in general, tissues found to be abnormal on clinical examination or by further investigation (e.g. skin, muscle, sural nerve or liver) should be considered first for diagnostic biopsy in undifferentiated systemic vasculitis.

Biopsy of a lip minor salivary gland may be useful to confirm Sjögren’s syndrome.

Biopsy of a lip minor salivary gland may be useful to confirm Sjögren’s syndrome.

Temporal artery biopsy is often diagnostic in patients with clinical features of temporal (giant cell) arteritis. This is the investigation of choice.

Temporal artery biopsy is often diagnostic in patients with clinical features of temporal (giant cell) arteritis. This is the investigation of choice.

Synovial biopsy is of little value in the differential diagnosis of inflammatory polyarthritis, but should be considered in any unusual monoarthritis to exclude infection, particularly tuberculous, or rare conditions such as sarcoid, amyloid arthropathy or villonodular synovitis.

Synovial biopsy is of little value in the differential diagnosis of inflammatory polyarthritis, but should be considered in any unusual monoarthritis to exclude infection, particularly tuberculous, or rare conditions such as sarcoid, amyloid arthropathy or villonodular synovitis.

Bone biopsy. May be useful in the diagnosis of osteomalacia, malignancy, renal osteodystrophy and Paget’s disease. The bone marrow can also be aspirated at the same time if necessary.

Bone biopsy. May be useful in the diagnosis of osteomalacia, malignancy, renal osteodystrophy and Paget’s disease. The bone marrow can also be aspirated at the same time if necessary.

Radiological examination

Certain general principles are important, particularly as clinicians may be asked to give an opinion on radiographs of limbs after traumatic injury, whether minor or more serious (Box 13.12). Common problems are shown in Figures 13.54–13.57. A systematic approach is essential (Box 13.13).

Box 13.12 General principles of musculoskeletal imaging

Use a systematic approach (see Box 13.13)

Use a systematic approach (see Box 13.13)

Age, sex and clinical information are essential in interpretation

Age, sex and clinical information are essential in interpretation

Radiographs reveal bones and soft tissues

Radiographs reveal bones and soft tissues

Always obtain two views, at right angles, in trauma patients

Always obtain two views, at right angles, in trauma patients

Radiographs may be normal even in the presence of disease

Radiographs may be normal even in the presence of disease

Diffuse abnormalities are difficult to detect

Diffuse abnormalities are difficult to detect

Figure 13.54 Healed fracture of posterior left and right ribs in a 6-month-old infant, classic non-accidental injury (NAI).

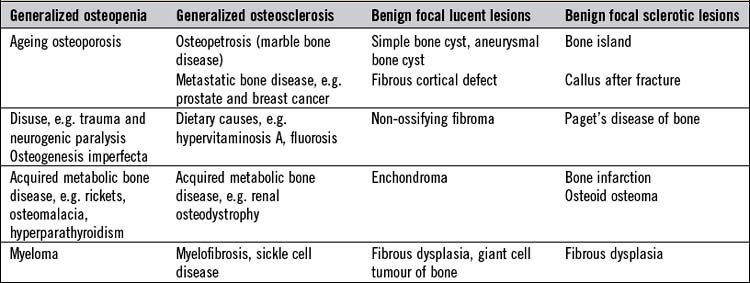

Bone density (Table 13.3) may be normal, reduced (osteopenia) or increased (osteosclerosis). These changes are easy to detect if focal, but difficult if diffuse. When a focal bone lesion (Box 13.14) is noted, look at its position in the bone and at its margins, and note whether there is any focal matrix calcification, whether the cortex of the bone is intact and whether there is any periosteal reaction around it. Most solitary bone lesions in young people are benign and show no periosteal reaction or swelling around them, and no associated soft-tissue swelling. Aggressive (malignant) bone lesions are more common in the elderly. Certain bone metastases have a characteristic appearance (Box 13.15). Isotope imaging is useful in detecting multiple sites of bony involvement in generalized disease and in metastatic cancer. CT imaging is also sensitive in detecting and analysing bony lesions, as it provides good images of the bony margins of the lesions and of the associated soft tissues. MRI is used to assess the extent of the lesion and any local soft tissue invasion.

Fractures

Only radiographs likely to yield specific information should be requested. However, in unilateral joint disease, it is useful to examine both sides for comparison (Fig. 13.58). In patients with inflammatory polyarthritis, three routine films are helpful in the diagnosis and assessment of progression: both hands and wrists on one plate, both feet on another, to compare bone density and to look for periosteal reaction or erosive change, and one of the full pelvis (Fig. 13.59) to show the sacroiliac and hip joints. In the absence of so-called ‘red flag’ signs, for example weight loss, night pain, fevers or neurological signs, most spinal radiographs are unnecessary.

Specialized radiology

High-resolution ultrasound is of value in defining soft-tissue structures, including muscles and tendons, and provides an excellent means for guiding aspiration of joint effusions and biopsy procedures. It is also used in the early detection of bone oedema and erosions in inflammatory arthritis.

High-resolution ultrasound is of value in defining soft-tissue structures, including muscles and tendons, and provides an excellent means for guiding aspiration of joint effusions and biopsy procedures. It is also used in the early detection of bone oedema and erosions in inflammatory arthritis.

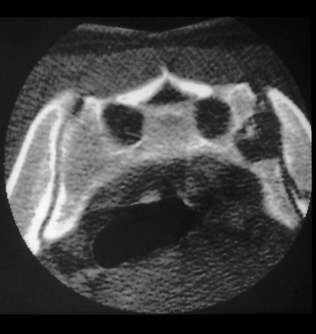

CT. The combination of superior tissue contrast and tomographic technique permits definition of soft-tissue structures obscured by overlapping structures, including intervertebral discs and other joints normally difficult to visualize, such as sacroiliac (Fig. 13.60), sternoclavicular and subtalar.

CT. The combination of superior tissue contrast and tomographic technique permits definition of soft-tissue structures obscured by overlapping structures, including intervertebral discs and other joints normally difficult to visualize, such as sacroiliac (Fig. 13.60), sternoclavicular and subtalar.

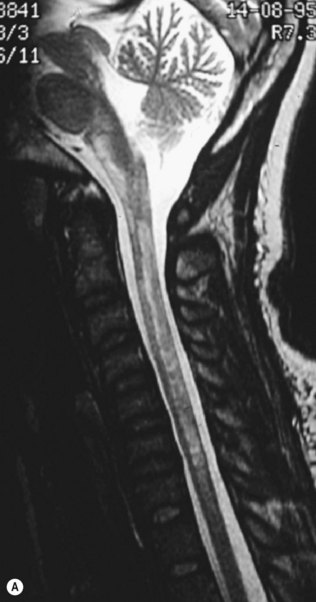

MRI has unique advantages in evaluating the musculoskeletal system, but it is vital that the clinician defines the pathology suspected, as correct positioning and sequence selection (T weighting) are vital in optimizing image quality. MRI is increasingly used to image the major joints in the limbs, especially the knee (see Fig. 13.45), hip, shoulder and elbow. Enhancement by the use of intravenous paramagnetic contrast (e.g. gadolinium) has further improved definition in spinal imaging and in documenting early synovitis. It is of particular value in the non-invasive investigation of disc disease (Fig. 13.61), including spinal infection, and is a sensitive technique for the diagnosis of avascular necrosis. MRI scanning of the brain and spine is the single most important investigation in neuroimaging, as the neural tissues themselves, together with supporting tissues, are well visualized. Bone is less well seen with this technique. As a rule of thumb, most abnormalities appear dark on T1-weighted images and white on T2-weighted images. Some common problems are shown in Figures 13.53, 13.61 and 13.62.

MRI has unique advantages in evaluating the musculoskeletal system, but it is vital that the clinician defines the pathology suspected, as correct positioning and sequence selection (T weighting) are vital in optimizing image quality. MRI is increasingly used to image the major joints in the limbs, especially the knee (see Fig. 13.45), hip, shoulder and elbow. Enhancement by the use of intravenous paramagnetic contrast (e.g. gadolinium) has further improved definition in spinal imaging and in documenting early synovitis. It is of particular value in the non-invasive investigation of disc disease (Fig. 13.61), including spinal infection, and is a sensitive technique for the diagnosis of avascular necrosis. MRI scanning of the brain and spine is the single most important investigation in neuroimaging, as the neural tissues themselves, together with supporting tissues, are well visualized. Bone is less well seen with this technique. As a rule of thumb, most abnormalities appear dark on T1-weighted images and white on T2-weighted images. Some common problems are shown in Figures 13.53, 13.61 and 13.62.

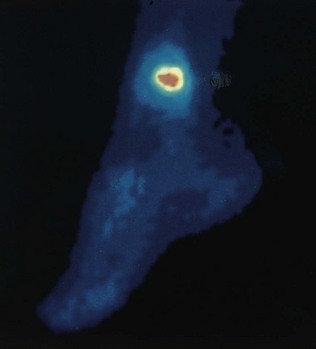

Isotopic scanning (scintigraphy) can be used in the diagnosis of acute (e.g. infection or stress fracture) or multiple (e.g. metastases) bone lesions by use of the first 2-minute (dynamic blood flow) phase, second 10-minute (blood pool) and third 3-hour late phase (osteoblastic) (Fig. 13.63) following intravenous injection of diphosphonate compounds. Tomographic scintigraphy can further refine definition of the isotope uptake (e.g. in stress fracture of the pars interarticularis).

Isotopic scanning (scintigraphy) can be used in the diagnosis of acute (e.g. infection or stress fracture) or multiple (e.g. metastases) bone lesions by use of the first 2-minute (dynamic blood flow) phase, second 10-minute (blood pool) and third 3-hour late phase (osteoblastic) (Fig. 13.63) following intravenous injection of diphosphonate compounds. Tomographic scintigraphy can further refine definition of the isotope uptake (e.g. in stress fracture of the pars interarticularis).

Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) is widely used to assess bone mineral density in metabolic bone disease and osteoporosis. Scans recorded with long intervals (e.g. every 2-3 years) between them may be used to assess the effects of therapy.

Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) is widely used to assess bone mineral density in metabolic bone disease and osteoporosis. Scans recorded with long intervals (e.g. every 2-3 years) between them may be used to assess the effects of therapy.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning is becoming more widely available but remains expensive. It is extremely sensitive in detecting malignancy and is also proving useful in documenting large vessel inflammation in disorders such as Takayasu’s arteritis and giant cell arteritis.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning is becoming more widely available but remains expensive. It is extremely sensitive in detecting malignancy and is also proving useful in documenting large vessel inflammation in disorders such as Takayasu’s arteritis and giant cell arteritis.

Figure 13.60 CT scan of sacroiliac joints, showing distinctive lesion on the left side with a sequestrum due to tuberculosis.