42 Liver Disorders

• Causes of jaundice are best categorized by the fraction of measured bilirubin implicated in disease—unconjugated or conjugated hyperbilirubinemia.

• The possibility of cerebral edema should be considered in patients with advanced liver disease and nausea, vomiting, and changes in mental status.

• As a result of the uncertain relationship of measured serum ammonia and cerebral ammonia concentration, patients with known or suspected hepatic encephalopathy should be treated for hyperammonemia regardless of the measured level.

• The prevalence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is high in cirrhotic patients, with rates of 3.5% in those with no symptoms to 30% in patients who seek treatment in a hospital for any reason and undergo paracentesis.

• Hepatitis B virus immune globulin effectively prevents transmission of hepatitis B virus if administered within 72 hours of exposure; it should be given for any high-risk exposure.

• Pyogenic liver abscesses are best treated with a combination of antibiotics and percutaneous drainage. Antibiotics alone are insufficient treatment.

Epidemiology

Chronic liver disease accounts for 70,000 hospitalizations annually in the United States and is one of the top 10 leading causes of death. Almost half of the 40,000 deaths per year in the United States are related to alcohol abuse. Although the majority of deaths are due to chronic liver disease and cirrhosis, 2000 deaths per year are associated with fulminant hepatic failure.1 Many of these patients die while awaiting liver transplantation. Hepatitis B and hepatitis C infections account for 40% of chronic liver disease, although many of these cases are exacerbated by concomitant alcohol abuse.

Common Signs and Symptoms of Liver Disease

Jaundice

Pancreatic and biliary cancer associated with jaundice may be manifested as pain.2 Patients with cirrhosis from chronic hepatitis are likely to describe painless jaundice but also complain of fatigue, pruritus, and constitutional symptoms. Patients who are acutely ill with jaundice, nausea, emesis, and fever should be tested for causes of acute hepatitis; similar manifestations without fever occur in toxic ingestions.

Hepatomegaly

In patients with hepatomegaly, the liver becomes significantly enlarged and easily palpable as a result of sudden edema from hepatitis or the appearance of fatty infiltrates with alcohol binging. If the enlargement is significant enough to cause portal hypertension, the spleen is often enlarged and palpable as well. As the liver scars and hepatocytes are replaced by fibrous tissue in cirrhosis, the organ shrinks and eventually becomes small and nodular. The presence or absence of hepatomegaly on examination is an unreliable estimate of liver function and should not be used to exclude a particular diagnosis.3,4

Signs and Symptoms of Advanced Liver Disease

Encephalopathy

The second and more easily measurable toxicity results from an increased ammonia concentration. The serum ammonia concentration rises as liver function declines, with intermittent fluctuations occurring in chronically ill patients. Many factors affect ammonia production, including changes in diet, constipation, hepatorenal syndrome, and gastrointestinal bleeding. Ammonia readily crosses the blood-brain barrier, and in patients with hepatic encephalopathy, ammonia causes cerebral toxicity, which promotes mental status decline and eventually coma.5–7

Ammonia is clearly toxic, and in animal models, ammonia infusions alone have been directly linked to the development of cerebral edema. In the setting of acute liver failure, ammonia levels higher than 200 mcg/dL are strongly associated with the development of cerebral edema and herniation.8–10 In patients with advanced liver disease and cirrhosis, however, mental status may not correlate directly with measured ammonia levels. Ammonia tends to accumulate in the brain, and although blood levels may be normal, the patient may still have enough ammonia in cerebrospinal fluid to induce encephalopathy.

Because of the uncertain relationship of the measured serum ammonia and cerebral ammonia concentration, patients with known or suspected hepatic encephalopathy should be treated for hyperammonemia regardless of measured serum levels. No convincing evidence suggests that arterial sampling for measurement of ammonia is superior to venous measurements.7

Treatment

Emergency department (ED) management of hepatic encephalopathy consists of appropriate airway control and resuscitation, followed by the administration of ammonia-lowering agents. Lactulose (15 to 45 mL once or twice daily) is the most common treatment of choice in the United States, although sodium benzoate has been shown to be equally effective and less expensive.11 Lactulose is a nonabsorbable disaccharide that decreases intestinal transit time through a direct cathartic effect, thus lowering intestinal bacterial loads. Lactulose also lowers intestinal pH, which favors competitive non–ammonia-producing bacteria. Lactulose may be given orally, by nasogastric tube, or in severely obtunded patients, as a retention enema.12

Neomycin is a poorly absorbed aminoglycoside used as secondary treatment to further reduce intestinal bacterial counts. Even though it is poorly absorbed, neomycin does cause systemic toxicity and should be used only when lactulose is ineffective. Mannitol (0.5 to 1 g/kg) effectively reduces cerebral edema and improves survival in patients with hepatic encephalopathy secondary to acute liver failure.8,13

The following therapies have been shown to be ineffective and should be avoided: hyperventilation,8,14 corticosteroids,8,13 and terlipressin.15

Ascites

Ascites associated with cirrhosis has a poor prognosis. One episode of ascites has a 3-year mortality rate of 50%, and recurrent ascites has the same 50% mortality at 1 year.16,17 Comorbid conditions contribute to mortality, including the development of hepatocellular carcinoma, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, coma, and infection.

One important infectious cause of death in patients with ascites is spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP). The prevalence of SBP in cirrhotic patients is high, with rates of 3.5% in asymptomatic patients to 30% in patients who seek treatment in a hospital for any reason and undergo paracentesis.18,19

Paracentesis for the relief of tense ascites has been shown to improve cardiac function.20 Reduction of intraabdominal hypertension and resolution of an effective abdominal compartment syndrome improve venous return to the heart.21

Patients with symptomatic ascites require paracentesis. Given the high rate of occult SBP in these patients, peritoneal fluid should always be sent for analysis. Previously, it was thought that large-volume paracentesis was associated with complications and should be avoided, but this common misperception has been disproved. Large-volume (>5 L) paracentesis is safe and is associated with shorter hospitalization than is the case with diuretic therapy in patients with refractory ascites.22,23

Complications of paracentesis are rare, even in thrombocytopenic patients. Most complications involve bleeding or persistent leakage from the puncture site and occur within 24 hours. Patients with such complications should be admitted to the hospital for observation.24,25

Controversy exists regarding volume expansion with colloids in conjunction with paracentesis. Studies have not demonstrated any short-term improvements in mortality or morbidity with the use of plasma expanders, although some alterations in renal function, such as elevations in blood urea nitrogen and decreased sodium levels (both of which are associated with a worse prognosis), have been observed. Albumin is the least expensive, safest, and usually most effective colloid for intravascular volume expansion and should be used in patients with paracentesis volumes of 5 L or larger.26–28

Paracentesis is improved when ultrasonography is used to identify ascites and guide the paracentesis. In one study, paracentesis performed under ultrasonographic guidance was successful in 95% of patients as opposed to 65% of procedures without such guidance.29

Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis

SBP is thought to be caused by translocation of intestinal flora, although this long-held premise is now under question. Previously, SBP was almost entirely associated with gram-negative bacteria, mostly Escherichia coli; a growing number of patients with SBP now have gram-positive organisms.30

The diagnosis is confirmed by culture of peritoneal fluid aspirated during paracentesis. SBP is likely if peritoneal fluid neutrophil counts are greater than 250 cells/µL. Peritoneal fluid lactate levels may be even more accurate.26,27

Patients with suspected SPB should have as much fluid drained as possible. Empiric antibiotic treatment should begin as soon as the diagnosis is considered. SBP in cirrhotic patients carries a mortality rate of 20% to 40%, with a 1-year survival rate of just 40%.26 Treatment should begin with a third-generation cephalosporin, such as ceftriaxone or cefotaxime. Quinolones should not be used because bacterial resistance to these agents is high and will worsen if the incidence of gram-positive infections continues to rise. Failure rates have been increasing regardless of which antibiotic regimen is used—it is often necessary to tailor individual therapy to the organisms found on culture.31

Portal Hypertension

Abdominal wall: Varices involving the abdominal wall are called caput medusae, so named for their serpentine appearance. They arise from dilation of the abdominal wall and umbilical veins.

Rectum: Hemorrhoids represent a form of rectal varices. They are often friable and subject to significant bleeding.

Esophagus: Esophageal varices are a common source of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with portal hypertension. Bleeding may be massive and difficult to control because of concomitant coagulopathy.

Hyponatremia

Cirrhotic patients have impaired excretion of free water. Low sodium levels, found in a third of all patients with cirrhosis, contribute to ascites, frequent falls, and cognitive decline. Hyponatremia is associated with a decreased response to diuretic therapy and a poor prognosis.32 In 2009 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the novel drug tolvaptan for the treatment of hyponatremia; tolvaptan acts as a vasopressin antagonist. As with any new pharmaceutical class, data are limited, but the early results are promising.33

Infectious Causes of Liver Disease

Hepatitis A Virus

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) is a single-stranded RNA enterovirus in the disease-producing family Picornaviridae, which also includes poliovirus. Also known as epidemic hepatitis because of its ability to spread swiftly and suddenly, HAV infects an average of 60,000 individuals annually worldwide. Transmission is fecal-oral, as in settings such as day care, or through sexual contact. It may also be transmitted by contaminated water or food sources; shellfish is a common vector, although seemingly innocuous food sources, such as imported lettuce, have been implicated in outbreaks as well.35,36

Hepatitis B Virus

More than 1 million individuals have chronic HBV infection in the United States, and approximately 500 million are infected worldwide. From 1990 to 2004, the overall incidence of reported acute HBV infection declined 75% through vaccination efforts, from 8.5 to 2.1 per 100,000 persons.37–39

Hepatitis C Virus

An RNA virus that is extremely complex and diverse, hepatitis C virus (HCV) has at least six distinct genotypes and 50 subtypes. This genetic diversity complicates development of a vaccine against it. HCV infection is the leading reason for liver transplantation; chronic infection commonly causes cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.38 Transmission occurs through sexual contact and sharing needles with infected individuals.

HCV transmission peaked in the United States in the 1980s before its discovery, with an estimated 250,000 new cases per year in that decade. Infection rates have dropped to approximately 40,000 annually. Carriers with chronic HCV infection number almost 3 million.40 The prevalence of HCV in trauma patients is 15% to 20%.41,42

Amebiasis

Amebic liver infections are of growing concern in the United States, although the infection is much more prevalent in the developing world. Amebiasis affects 50 million persons worldwide and is estimated to cause 50,000 to 100,000 deaths per year.43

Amebiasis is frequently manifested as colitis. It is unknown what percentage of cases progress to abscess formation, although approximately one third of patients with abscesses have prodromal nausea, emesis, diarrhea, and bloating.44,45 Solitary abscess formation is common in patients with amebic abscesses, as opposed to the multiple foci often seen in those with pyogenic abscesses. Amebic abscesses have a predilection for males, with a 10 : 1 ratio of infection; such gender bias is not seen with pyogenic abscesses.

Diagnosis

Most patients in the United States in whom amebic liver abscess is diagnosed are seen in the southwestern states and are males of Mexican origin.46 The symptoms may mimic those of cholecystitis, with right upper quadrant abdominal pain, fever, chills, and nausea. In one series, 20% of patients with amebiasis had isolated pulmonary complaints.46

Abscesses are easily seen on ultrasonography. The ultrasonographic appearance in combination with acute symptoms makes the diagnosis in at least two thirds of patients.45,47,48 Computed tomography (CT) is sensitive as well and should be used when the diagnosis is in question.

Treatment and Prognosis

Metronidazole remains the first-line treatment (a high-dose schedule consisting of 750 mg three times daily for 10 days provides a 90% cure rate).49 Aspiration has traditionally been recommended for abscesses larger than 5 cm, although the results of studies examining this practice are equivocal.50,51

Pyogenic Liver Abscesses

Liver abscesses in the United States and worldwide are most often due to amebiasis, although pyogenic abscesses represent a more serious condition. Pyogenic abscesses were diagnosed in 3000 patients per year in one European study.52

Diagnosis

Because the causes of pyogenic abscesses are so varied, the abscesses are not manifested in a uniform fashion. Right upper quadrant tenderness and hepatomegaly are noted in approximately 50% of cases.53 Patients commonly show signs of systemic disease, such as fever, malaise, weight loss, and anorexia.

Liver function values may or may not be elevated and should not be used to exclude the diagnosis. Ultrasonography and CT are both excellent imaging modalities, with sensitivities of 85% and 95%, respectively.53,54

Treatment and Prognosis

Pyogenic liver abscesses are treated with a combination of antibiotics and drainage. Catheter drainage and needle aspiration produce similar success rates of 60% to 90%, although these two options have not been compared directly. The largest published trials have demonstrated success rates exceeding 95% with ultrasound-guided aspiration without catheter placement followed by broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics (to cover gram-positive, gram-negative, and anaerobic organisms).55,56 Antibiotic therapy without abscess drainage is generally unsuccessful.

Parasitic Infections

Diagnosis

ED patients with hepatobiliary symptoms after travel to Asia should be considered at high risk for parasitic infection. Ultrasonography and CT may show indirect signs of infection, such as biliary stones and dilation; these imaging methods are not helpful for identifying the organisms themselves.57

Noninfectious Liver Disorders

Alcoholic Liver Disease

Alcohol consumption is responsible for half of all chronic liver disease in the United States.1 Alcohol may poison the liver acutely or may damage hepatocytes through repeated insult, with permanent destruction of hepatic architecture and the eventual development of cirrhosis. Alcohol consumption causes accumulation of fat in the liver that displaces hepatocytes; the accumulation is normally reversible, but if the liver is subject to repeated insult, the accumulation of fat slowly becomes permanent. Chronic fatty liver is subject to inflammatory changes that induce scarring and permanent replacement of functional hepatocytes with lipocytes and fibrous tissue. The smaller numbers of hepatocytes cannot handle the physiologic requirements of the body. This pathologic progression is significantly accelerated by coexisting HCV or HBV infection.60 Women are much more prone to alcohol-induced hepatic injury.61

Treatment and Prognosis

Treatment is mostly supportive, although as with other forms of liver disease, both coagulopathy and changes in mental status should be treated aggressively. The mortality rate in hospitalized patients with alcoholic hepatitis is approximately 10%.62 Higher mortality is observed when patients have concomitant encephalopathy and coagulopathy; immediate liver transplantation may be required for their survival.

Corticosteroid use in hospitalized patients with alcoholic hepatitis is controversial. During the 1980s and early 1990s, a number of published studies proclaimed significant reductions in mortality with the use of corticosteroids (particularly convincing was one study of the use of prednisolone in 199263). However, a carefully performed metaanalysis published in 1995 that examined 12 controlled trials did not find any benefit.64 The use of corticosteroids should be reserved for inpatient units and not be initiated in the ED.

Autoimmune Liver Disorders

Patients with autoimmune liver disorders have progressive disease and a survival rate of 10% to 50% at 5 years if untreated. As the disease advances, the patient exhibits signs of liver insufficiency similar to those in other patients with chronic liver disease.65,66

The prognosis has improved with liver transplantation, which provides a 10-year survival rate of 75%; recurrence is seen in 42% of patients.67

Drug-Induced Liver Disease

Many pharmaceutical and naturally occurring substances can cause catastrophic liver injury (Box 42.1). The manifestation of drug-induced liver disease varies from benign jaundice to fulminant hepatic failure. Almost 40% of cases of acute hepatic failure in the United States are caused by drug-induced injury; almost half of these cases are due to acetaminophen alone.68,69

Care of Patients with Liver Transplants

More than 36,000 patients living in the United States have undergone liver transplantation.70 Transplantation patients come to the ED with common complaints, such as fever and abdominal pain, which are associated with high morbidity in this population. Almost 70% of liver transplant recipients who seek care in an ED require hospitalization.71

Infectious Complications

The most common serious infection seen in the first few months after transplantation is cytomegalovirus, which is manifested as fever, arthralgias, and malaise. Other viral infections, such as herpes simplex virus, varicella-zoster virus, and herpes zoster virus, are also common but are not as serious as cytomegalovirus.70 Infections with fungi such as Candida should also be suspected.

Mechanical Complications

Liver transplant recipients are subject to vascular or structural problems surrounding and within the transplant. Hepatic artery stenosis and hepatic artery thrombosis are each present in approximately 10% of liver transplant recipients, frequently because of rejection. Either stenosis or thrombosis of the hepatic artery can be manifested as abdominal pain, and both are accurately detected with ultrasonography.71 Timely discussion with a transplant team and early use of angiography are recommended because of the need for a rapid decision on corrective treatment.

Finally, the biliary tree is also affected by stenosis or ischemia in approximately 10% of patients and is diagnosed by ultrasonography or anigiography.72

Liver Function Tests

Alanine Transaminase And Aspartate Transaminase

Both ALT and AST, which are called transaminases, are concentrated intrahepatocyte enzymes (although AST exists in measurable quantities elsewhere in the body as well). Any hepatocyte necrosis elevates these enzymes. The often quoted 2 : 1 ratio of AST to ALT in patients with alcoholic liver disease is not supported by the literature.73,74

Chronic disease states such as HCV, alcoholic cirrhosis, and autoimmune hepatitis are often associated with persistent elevations in ALT and AST, although normal values should not be used to exclude the possibility of disease. More than 15% of patients with biopsy-proven chronic HCV disease have transaminase elevations.75

Bilirubin

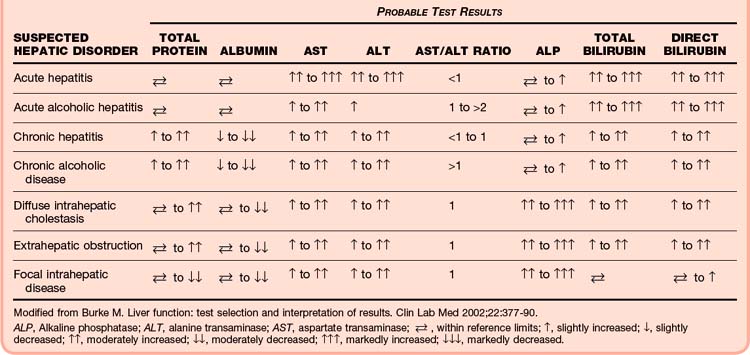

Understanding this process of bilirubin metabolism helps focus the differential diagnosis of patients with hyperbilirubinemia or jaundice, or with both (Tables 42.1 and 42.2). Unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia results from increased production of bilirubin (hemolysis) or from decreased uptake in the liver (as seen in various inherited conditions). Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia results from loss of excretory capacity, which can occur as a result of intrahepatic diseases (e.g., drug reactions, hepatitis, cirrhosis) or biliary obstruction. Obstructive jaundice is due to a lesion that blocks the excretion of bile through the biliary ducts, either proximally at the hepatic duct or more distally at the common bile duct.73,76

| TYPE | CAUSE | CLINICAL FEATURES AND BIOCHEMICAL ABNORMALITIES |

|---|---|---|

| Unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia | Hemolysis | Decreased hemoglobin and haptoglobin levels Increased reticulocyte count |

| Gilbert syndrome | None | |

| Hematoma reabsorption | Increased creatine kinase and lactic dehydrogenase levels | |

| Ineffective erythropoiesis | — | |

| Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia | Bile duct obstruction | Preceded by a marked increase in transaminase levels Presence of suggestive symptoms (right upper quadrant pain, nausea, fever) |

| Hepatitis (various causes) | Concomitant moderate to marked increase in transaminase levels | |

| Cirrhosis | Transaminase levels may be normal or only slightly increased Presence of other physical and instrumental signs of chronic liver disease |

|

| Autoimmune cholestatic diseases (primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis) | Marked increase in ALP levels with normal or mildly increased transaminase levels Presence of other autoimmune diseases or associated diseases (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease) |

|

| Total parenteral nutrition | Increased ALP and γ-glutamyltransferase levels | |

| Drug toxins | Concomitant increase in ALP levels | |

| Vanishing bile duct syndrome | Can be associated with drug reactions or occur with orthotopic liver transplantation |

ALP, Alkaline phosphatase.

From Giannini E, Testa R, Savarino V. Liver enzyme alteration: a guide for clinicians. CMAJ 2005;172:367-79.

Burke M. Liver function: test selection and interpretation of results. Clin Lab Med. 2002;22:377–390.

Cardenas A. Hepatorenal syndrome: a dreaded complication of end-stage liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:460–467.

Evans LT. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in asymptomatic outpatients with cirrhotic ascites. Hepatology. 2003;37:897–901.

Knox T, Olans L. Liver disease in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:569–576.

Polson J, Lee WM. American Association for the Study of Liver Disease: AASLD position paper: the management of acute liver failure. Hepatology. 2005;41:117997.

1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Deaths and hospitalizations from chronic liver disease and cirrhosis—United States, 1980-1989. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1993;41(52-53):969–973.

2 Modolell I. Vagaries of clinical presentation of pancreatic and biliary tract cancer. Ann Oncol. 1999;10(Suppl 4):82–84.

3 Zoli M. Physical examination of the liver: is it still worth it? Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1428–1432.

4 Tucker WN. The scratch test is unreliable for detecting the liver edge. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;25:410–414.

5 Basile AS, Jones EA. Ammonia and GABA-ergic neurotransmission: interrelated factors in the pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology. 1997;25:1303–1305.

6 Lockwood AH, Bolomey L, Napoleon F. Blood-brain barrier to ammonia in humans. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1984;4:516–522.

7 Lockwood AH. Blood ammonia levels and hepatic encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis. 2004;19:345–349.

8 Polson J, Lee WM. American Association for the Study of Liver Disease: AASLD position paper: the management of acute liver failure. Hepatology. 2005;41:1179–1197.

9 Clemmensen JO, Larsen FS, Knodrup J, et al. Cerebral herniation in patients with acute liver failure is correlated with arterial ammonia concentration. Hepatology. 1999;29:648–653.

10 Blei AT, Olafsson S, Therrien G, et al. Ammonia induced brain edema and intracranial hypertension in rats after portacaval anastomosis. Hepatology. 1994;19:1437–1444.

11 Sushma S, Dasarathy S, Tandon RK, et al. Sodium benzoate in the treatment of acute hepatic encephalopathy: a double-blind randomized trial. Hepatology. 1992;16:138–144.

12 Alba L, Hay JE, Angulo P, et al. Lactulose therapy in acute liver failure. J Hepatol. 2002;36:33A.

13 Canalese J, Gimson AES, Davis C, et al. Controlled trial of dexamethasone and mannitol for the treatment of fulminant hepatic failure. Gut. 1982;23:625–629.

14 Ede RJ, Gimson AE, Bihari D, et al. Controlled hyperventilation in the prevention of cerebral edema in fulminant hepatic failure. J Hepatol. 1986;2:43–51.

15 Shawcross D. Worsening of cerebral hyperemia by the administration of terlipressin in acute liver failure with severe encephalopathy. Hepatology. 2004;39:471–475.

16 Moreau R. Clinical characteristics and outcome of patients with cirrhosis and refractory ascites. Liver Int. 2004;24:457–464.

17 D’Amico G, Morabito A, Pagliaro L, et al. Survival and prognostic indicators in compensated and decompensated cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 1986;31:468–475.

18 Jepsen P. Prognosis of patients with liver cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:2133–2136.

19 Evans LT. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in asymptomatic outpatients with cirrhotic ascites. Hepatology. 2003;37:897–901.

20 Guazzi M. Negative influences of ascites on the cardiac function of cirrhotic patients. Am J Med. 1975;59:165–170.

21 Malbrain M, Chiumello D, Pelosi P, et al. Incidence and prognosis of intraabdominal hypertension in a mixed population of critically ill patients: a multiple-center epidemiological study. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:315–322.

22 Gines P, Arroyo V, Quintero E, et al. Comparison of paracentesis and diuretics in the treatment of cirrhotics with tense ascites: results of a randomized study. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:234–241.

23 Choi CH. Efficacy and safety of large volume paracentesis in cirrhotic patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a randomized prospective study. Taehan Kan Hakhoe Chi. 2002;8:52–60.

24 Peltekian KM. Cardiovascular, renal, and neurohumoral responses to single large-volume paracentesis in patients with cirrhosis and diuretic-resistant ascites. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:394–399.

25 Webster ST. Hemorrhagic complications of large volume abdominal paracentesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:366–368.

26 Ginès P, Arroyo V, Rodés J. Pathophysiology, complications, and treatment of ascites. Clin Liver Dis. 1997;1:129–155.

27 Gines P, Tito L, Arroyo V, et al. Randomized comparative study of therapeutic paracentesis with and without intravenous albumin in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1988;94:1493–1502.

28 Nasr G, Hassan A, Ahmed S. Predictors of large volume paracentesis induced circulatory dysfunction in patients with massive hepatic ascites. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2010;1:136–144.

29 Naxeer S, Dewbre H, Miller A. Ultrasound assisted paracentesis performed by emergency physicians vs the traditional technique: a prospective randomized study. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23:363–367.

30 Cholongitas E, Papatheodoridis GV, Lahanas A, et al. Increasing frequency of gram-positive bacteria in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Liver Int. 2005;25:57–61.

31 Angeloni S, Leboffe C, Parente A. Efficacy of current guidelines for the treatment of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in the clinical practice. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:2757–2762.

32 Arroyo V. Prognostic value of spontaneous hyponatremia in cirrhosis with ascites. Am J Dig Dis. 1976;21:249–256.

33 Schrier RW, Gross P, Gheorghiade M, et al. for the SALT Investigators. Tolvaptan, a selective oral vasopressin V2-receptor antagonist, for hyponatremia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2099–2112.

34 Cardenas A. Hepatorenal syndrome: a dreaded complication of end-stage liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:460–467.

35 U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition. Hepatitis A virus. In: Foodborne pathogenic microorganisms and natural toxins handbook. Available at http://vm.cfsan.fda.gov/~mow/chap31.html/

36 Kemmer N, Miskovsky E, Hepatitis A. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2000;14:605–615.

37 Lin K, Kerchner J, Hepatitis B. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:75–82.

38 Hayashi P, Bisceglie A. The progression of hepatitis B and C infections to chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and pathogenesis. Med Clin North Am. 2005;89:371–389.

39 Diehl A. Alcoholic liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 1998;2:103–118.

40 Boyer J, Chang E, Collyar D, et al. NIH consensus statement: management of hepatitis C: 2002. Available at http://consensus.nih.gov/2002/2002HepatitisC2002116html.htm

41 Brillman JC. Prevalence and risk factors associated with hepatitis C in ED patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:476–480.

42 Caplan E, Preas M, Micheal A, et al. Seroprevalence of human immunodeficiency virus, HBV, HCV, and RPR in a trauma population. J Trauma. 1995;39:533–538.

43 World Health Organization. Amoebiasis. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 1997;72:97–99.

44 Hai AA. Amoebic liver abscess: review of 220 cases. Int Surg. 1991;76:81–83.

45 Hughes MA, Petri WM, Jr. Amebic liver abscesses. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2000;14:565–582.

46 Hoffner R, Kilaghbian T, Esekogwu V, et al. Emergency department presentation of amebic liver abscesses. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:470–474.

47 Sharma MP. Amoebic liver abscess. Trop Gastroenterol. 1993;14:3–9.

48 Ralls PW. Focal inflammatory disease of the liver. Radiol Clin North Am. 1998;36:377–389.

49 Maltz G. Amebic liver abscesses: a 15 year experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:704–710.

50 Tandon A. Needle aspiration in large amoebic liver abscess. Trop Gastroenterol. 1997;18:19–21.

51 Blessmann J, Binh HD, Hung DM, et al. Treatment of amoebic liver abscess with metronidazole alone or in combination with ultrasound-guided needle aspiration: a comparative prospective and randomized study. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8:1030–1040.

52 Hansen PS, Schonheyder HC. Pyogenic hepatic abscess: a 10-year population-based retrospective study. APMIS. 1998;106:396–402.

53 Johannsen E. Pyogenic liver abscesses. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2000;14:547–563.

54 Seeto RK, Rockey DC. Pyogenic liver abscess: changes in etiology, management, and outcome. Medicine (Baltimore). 1996;75:99–113.

55 Giorgio A, Tarantino L, Mariniello N, et al. Pyogenic liver abscesses: 13 years of experience in percutaneous needle aspiration with US guidance. Radiology. 1995;195:122–124.

56 Ch Yu S, Hg Lo R, Kan PS, et al. Pyogenic liver abscess: treatment with needle aspiration. Clin Radiol. 1997;52:912–916.

57 Elliott D. Schistosomiasis: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterol Clin. 1996;25:599–625.

58 Lun ZR. Clonorchiasis: a key foodborne zoonosis in China. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:31–41.

59 Homeida MA. Association of the therapeutic activity of praziquantel with the reversal of periportal fibrosis induced by S. mansonii. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1991;45:360–365.

60 Lieber CS. Biochemical factors in alcoholic liver disease. Semin Liver Dis. 1993;6:136–147.

61 Saunders JB, Davis M, Williams R. Do women develop alcoholic liver disease more readily than men? Br Med J. 1981;282:1140–1143.

62 Fujimoto M, Uemura M, Kojima H. Prognostic factors in severe alcoholic liver injury. Nara Liver Study Group. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23(Suppl):33S–38S.

63 Ramond MJ, Poynard T, Rueff B, et al. A randomized trial of prednisolone in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:507–512.

64 Christensen E, Gluud C. Glucocorticoids are ineffective in alcoholic hepatitis: a meta-analysis adjusting for confounding variables. Gut. 1995;37:113–118.

65 Krawitt EL. Autoimmune hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:54–66.

66 Mabee C, Thiele D. Mechanisms of autoimmune liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2000;4:431–445.

67 Duclos-Vallee JC, Sebagh M, Rifai K, et al. A 10 year follow up study of patients transplanted for autoimmune hepatitis: histological recurrence precedes clinical and biochemical recurrence. Gut. 2003;52:893–897.

68 Lewis J. Drug-induced liver disease. Med Clin North Am. 2000;84:1275–1311.

69 Schiodt FV, Atillasoy E, Shakil AO, et al. Etiology and prognosis for 295 patients with acute liver failure. Liver Transpl Surg. 1999;5:29–34.

70 U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). Annual report 2005. Available at www.optn.org/

71 Dodd GD, 3rd., Memel DS, Zajko AB, et al. Hepatic artery stenosis and thrombosis in transplant recipients: Doppler diagnosis with resistive index and systolic acceleration time. Radiology. 1994;192:657–661.

72 Sheng R, Zajko AB, Campbell WL, et al. Biliary strictures in hepatic transplants: prevalence and types in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis vs those with other liver diseases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 161, 1993. 297-230

73 Pinto H, Babtisti A. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: clinicopathological comparison with alcoholic hepatitis in ambulatory and hospitalized patients. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:172–179.

74 Kew M. Serum aminotransferase concentration as evidence of hepatocellular damage. Lancet. 2000;355:591–592.

75 Gholson C, Morgan K. Chronic hepatitis C with normal aminotransferase levels: a clinical histologic study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1788–1792.

76 Burke M. Liver function: test selection and interpretation of results. Clin Lab Med. 2002;22:377–390.