16 Liver disease

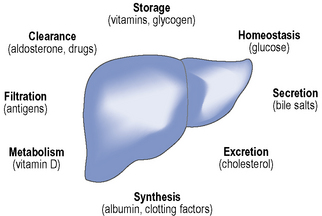

The liver weighs up to 1500 g in adults and as such is one of the largest organs in the body. The main functions of the liver include protein synthesis, storage and metabolism of fats and carbohydrates, detoxification of drugs and other toxins, excretion of bilirubin and metabolism of hormones, as summarised in Fig. 16.1. The liver has considerable reserve capacity reflected in its ability to function normally despite surgical removal of 70–80% of the organ or the presence of significant disease. It is noted for its capacity to regenerate rapidly. However, once it has been critically damaged multiple complications develop involving many body systems. The distinction between acute and chronic liver disease is conventionally based on whether the history is less or greater than 6 months, respectively.

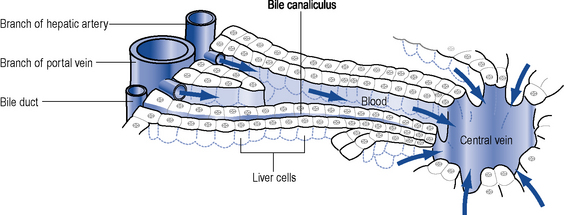

The hepatocyte is the functioning unit of the liver. Heptocytes are arranged in lobules and within a lobule hepatocytes perform different functions depending on how close they are to the portal tract. The portal tract is the ‘service network’ of the liver and contains an artery and a portal vein delivering blood to the liver and bile duct which forms part of the biliary drainage system (Fig. 16.2). The blood supply to the liver is 30% arterial and the remainder is from the portal system which drains most of the abdominal viscera. Blood passes from the portal tract through sinusoids that facilitate exposure to the hepatocytes before the blood is drained away by the hepatic venules and veins. There are a number of other cell populations in the liver, but two of the most important are Kuppfer cells, fixed monocytes that phagocytose bacteria and particulate matter, and stellate cells responsible for the fibrotic reaction that ultimately leads to cirrhosis.

Chronic liver disease

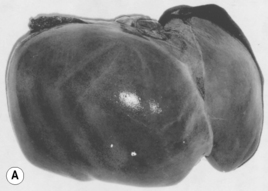

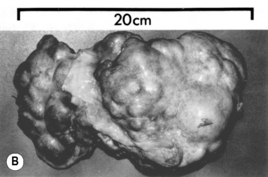

Chronic liver disease occurs when permanent structural changes within the liver develop secondary to long-standing cell damage, with the consequent loss of normal liver architecture. In many cases, this progresses to cirrhosis, where fibrous scars divide the liver cells into areas of regenerative tissue called nodules (Fig. 16.3). Conventional wisdom is that this process is irreversible, but therapeutic intervention in hepatitis B and haemochromatosis has now repeatedly documented cases of reversal of cirrhosis. Once chronic liver disease progresses, patients are at risk of developing liver failure, portal hypertension or hepatocellular carcinoma. Cirrhosis is a sequel of chronic liver disease of any aetiology and it develops over very variable time periods from 5 to 20 or more years.

Causes of liver disease

Immune disorders

Metabolic and genetic disorders

There are various inherited metabolic disorders that can affect the functioning of the liver.

Clinical manifestations

Signs of liver disease

Cutaneous signs

Hyperpigmentation is common in chronic liver disease and results from increased deposition of melanin. It is particularly associated with PBC and haemachromatosis. Scratch marks on the skin suggest pruritus which is a common feature of cholestatic liver disease. Vascular ‘spiders’ referred to as spider naevi are small vascular malformations in the skin and are found in the drainage area of the superior vena cava, commonly seen on the face, neck, hands and arms. Examination of the limbs can reveal several signs, none of which are specific to liver disease. Palmar erythema, a mottled reddening of the palms of the hands, can be associated with both acute and chronic liver disease. Dupuytren’s contracture, thickening and shortening of the palmar fascia of the hands causing flexion deformities of the fingers, was traditionally associated with alcoholic cirrhosis. It is now considered to be multifactorial in origin and not to reflect primary liver disease. Nail changes, highly polished nails or white nails (leukonychia) can be seen in up to 80% of patients with chronic liver disease. Leukonychia is a consequence of low serum albumin. Finger clubbing is most commonly seen in hypoxaemia related to hepato-pulmonary syndrome, but is also a feature of chronic liver disease (Table 16.1)

| Common findings | End-stage findings |

|---|---|

| Jaundice | Ascites |

| Gynaecomastia & loss of body hair | Dilated abdominal blood vessels |

| Hand changes: | Fetor hepaticus |

| Palmar erythema | Hepatic flap |

| Clubbing | Neurological changes: |

| Dupuytren’s contracture | Hepatic encephalopathy |

| Leuconychia | Disorientation |

| Liver mass reduced or increased | Changes in consciousness |

| Parotid enlargement | Peripheral oedema |

| Scratch marks on skin | Pigmented skin |

| Purpura | Muscle wasting |

| Spider naevi | |

| Splenomegaly | |

| Testicular atrophy | |

| Xanthelasma | |

| Hair loss |

Jaundice

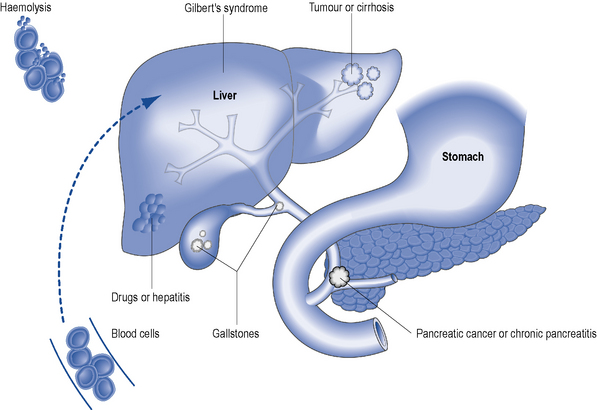

Jaundice is the physical sign regarded as synonymous with liver disease and is most easily detected in the sclerae. It reflects impaired liver cell function (hepatocellular pathology) or it can be cholestatic (biliary) in origin. Hepatocellular jaundice is commonly seen in acute liver disease, but may be absent in chronic disease until the terminal stages of cirrhosis are reached. The causes of jaundice are shown in Fig. 16.4.

Ascites

Investigations

Patient care

Pruritus

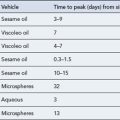

Opioid antagonists

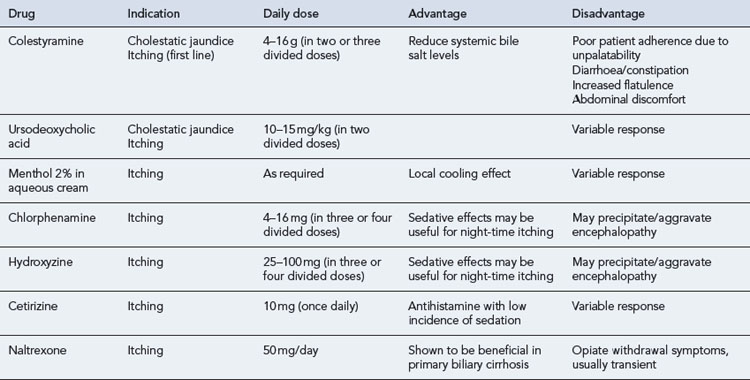

A growing spectrum of opioid antagonists have been used to treat pruritus because it is believed that endogenous opioids in the central nervous system are potent mediators of itch. As a consequence the centrally acting opioid antagonists naloxone, naltrexone and nalmefene are thought to reverse the actions of these endogenous opioids. The use of such agents is limited by their route of administration. Naloxone is given by subcutaneous injection, while naltrexone and nalmefene are reported to be more substantially bioavailable after oral administration. A summary of drugs used in the management of pruritus is shown in Table 16.2.

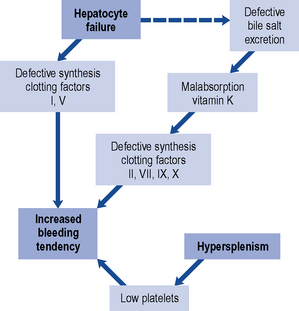

Clotting abnormalities

The relationship of liver disease to clotting abnormalities is shown diagrammatically in Fig. 16.5. Haemostatic abnormalities develop in approximately 75% of patients with chronic liver disease and 100% of patients with ALF. The majority of clotting factors (with the exception of factor V) are dependent on vitamin K. Patients with liver disease who develop deranged blood clotting should receive intravenous doses of phytomenadione (vitamin K), usually 10 mg daily for 3 days. Administration of vitamin K to patients with significant liver disease does not usually improve the prothrombin time because the liver is unable to utilise the vitamin to synthesis clotting factors. Oral vitamin K is less effective than the parenteral form and so, has little or no place in the management of clotting abnormalities and bleeding secondary to liver disease.

Ascites

Aggressive weight reduction in the absence of peripheral oedema should be avoided as it is likely to lead to intravascular fluid depletion and renal failure. Weight loss should not exceed 300–500 g/day in the absence of peripheral oedema and 800–1000 g/day in those with peripheral oedema to prevent renal failure. However, diuretics and/or paracentesis are the cornerstone in the management of moderate to large volume ascites. A sequential approach to the management of ascites is outlined in Box 16.1.

Box 16.1 The sequential approach to the management of cirrhotic ascites

Bedrest and sodium restriction (60–90 mEq/day, equivalent to 1500–2000 mg of salt/day)

Spironolactone (or other potassium-sparing diuretic)

Spironolactone and loop diuretic

Large-volume paracentesis and colloid replacement

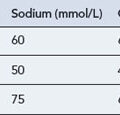

Diuretics

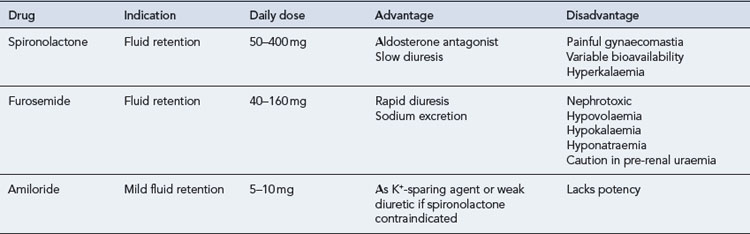

The aldosterone antagonist, spironolactone is usually used as a first-line agent in the treatment of ascites. In most instances, a negative sodium balance and loss of ascitic fluid can be achieved with low doses of diuretics. Spironolactone can be used alone or in combination with a more potent loop diuretic. The specific agents and dosages used are outlined in Table 16.3. Spironolactone acts by blocking sodium reabsorption in the collecting tubules of the kidney. It is usually commenced at 50–100 mg/day, but this varies, depending on the patient’s clinical status, electrolyte levels and concomitant drug therapies. It can take many days to have a therapeutic effect, so dose augmentation should be conducted with caution and strict observation of renal parameters. The addition of a loop diuretic, furosemide 40 mg/day enhances the natriuretic activity of spironolactone, and should be used when ascites is severe or when spironolactone alone fails to produce acceptable diuresis.

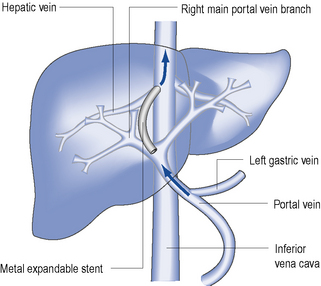

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting (TIPS)

TIPS is an invasive procedure, used to manage refractory ascites or control refractory variceal bleeding. It is carried out under radiological guidance. An expandable intrahepatic stent is placed between one hepatic vein and the portal vein by a transjugular approach (Fig. 16.6). In contrast to paracentesis, the use of TIPS is effective in preventing recurrence in patients with refractory ascites. It reduces the activity of sodium retaining mechanisms and improves the renal response to diuretics. However, a disadvantage of this procedure is the high rate of shunt stenosis (up to 30% after 6–12 months) which leads to recurrence of ascites. TIPS can also induce or exacerbate hepatic encephalopathy.

Hepatic encephalopathy

Clinical features of hepatic encephalopathy range from trivial lack of awareness, altered mental state to asterixis (liver flap) through to gross disorientation and coma. During low-grade encephalopathy, the altered mental state may present as impaired judgement, altered personality, euphoria or anxiety. Reversal of day/night sleep patterns is very typical of encephalopathy. Somnolence, semistupor, confusion and, finally, coma can ensue (Table 16.4).

| Grade 0 | Normal |

|---|---|

| Subclinical | Abnormal psychometric tests for encephalopathy (e.g. number correction test) |

| Grade 1 | Mood disturbance, abnormal sleep pattern, impaired handwriting +/− asterixis |

| Grade 2 | Drowsiness, grossly impaired calculation ability, asterixis |

| Grade 3 | Confusion, disorientation, somnolent but arousable, asterixis |

| Grade 4 | Stupor to deep coma, unresponsive to painful stimuli |

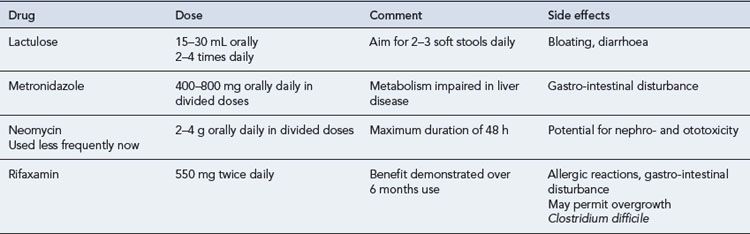

Encephalopathy associated with cirrhosis and/or portal-systemic shunts may develop as a result of specific precipitating factors (Box 16.2) or spontaneously. Common precipitating factors include gastro-intestinal bleeding, SBP, constipation, dehydration, electrolyte abnormalities and certain drugs including narcotics and sedatives. Identification and removal of such precipitating factors is mandatory. Therapeutic management is then aimed at reducing the amount of ammonia or nitrogenous products in the circulatory system. Treatment with laxatives increases the throughput of bowel contents, by reducing transit time and also increases soluble nitrogen output in the faeces. Drug therapies for encephalopathy are summarised in Table 16.5.

Antibiotics such as metronidazole or neomycin may also be used to reduce ammonia production from gastro-intestinal bacteria. Metronidazole has been the preferred option in the past, while the use of neomycin has largely been abandoned because of associated toxicity. Recent data has supported the use of the rifaximin, a minimally absorbed antibiotic, for the treatment of acute encephalopathy and the remission of chronic encephalopathy (Bass et al., 2010). Other therapies investigated for the treatment of encephalopathy include l-ornithine-l-aspartate (LOLA), sodium benzoate, l-dopa, bromocriptine and the benzodiazepine receptor antagonist, flumazenil.

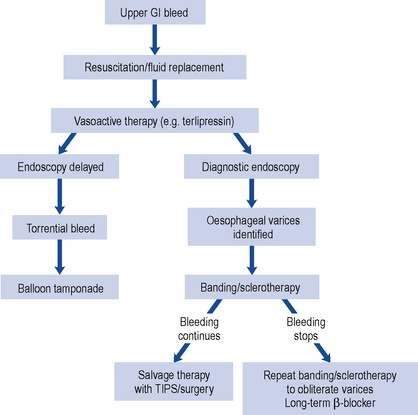

Oesophageal varices

Initial treatment is aimed at stopping or reducing the immediate blood loss, treating hypovolaemic shock, if present, and subsequent prevention of recurrent bleeding. Immediate and prompt resuscitation is an essential part of treatment. Only when medical treatment has been initiated and optimised should endoscopy be performed. Endoscopy confirms the diagnosis and allows therapeutic intervention. Fluid replacement is invariably required, and should be in the form of colloid or packed red cells and administered centrally. Saline should generally be avoided in all patients with cirrhosis. Fluid replacement must be administered with caution, as over-zealous expansion of the circulating volume may precipitate further bleeding by raising portal pressure, thereby exacerbating the clinical situation. A flow chart for the management of bleeding oesophageal varices is shown in Fig. 16.7.

Drug treatment

Several pharmacological agents are available for the emergency control of variceal bleeding (Table 16.6). Most act by lowering portal venous pressure. They are generally used to control bleeding in addition to balloon tamponade and emergency endoscopic techniques. Vasopressin was the first vasoconstrictor used to reduce portal pressure in patients with actively bleeding varices. However, its associated systemic vasoconstrictive adverse effects limited its use. The synthetic vasopressin analogue, terlipressin, is highly effective in controlling bleeding and in reducing mortality. It can be administered in bolus doses every 4–6 h and has a longer biological activity and a more favourable side effect profile. Once a diagnosis of variceal bleeding has been established, a vasoactive drug infusion (usually terlipressin) should be started without further delay and continued for 2–5 days. Somatostatin and the somatostatin analogue, octreotide, are reported to cause selective splanchnic vasoconstriction and reduce portal pressure. Although they are reported to cause less adverse effects on the systemic circulation, terlipressin remains the agent of choice.

Table 16.6 Drugs used in the treatment of acute bleeding varices

| Drug | Dosage and administration |

|---|---|

| Terlipressin | 1–2 mg bolus 4–6 hourly for 48 h |

| Octreotide | 50 μcg/h i.v. infusion for 48 h or longer if patient rebleeds |

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS)

TIPS is now established as the preferred rescue therapy in cases where endoscopic intervention has failed to control bleeding (Fig. 16.7). Recent data suggests the use of early TIPS, within the first 48 h, may be life saving in patients with advanced liver failure.

Disease specific therapies

Hepatitis B

It is the persistence of covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) which is considered to preclude a ‘cure’ for HBV. Thus, therapies currently available for the treatment of chronic HBV are measured in terms of HBeAg seroconversion (in eAg positive disease), viral suppression, ALT normalisation and improvement in liver histopathology. More recently, there has been specific focus on HBsAg quantification, with loss of HBsAg considered a surrogate marker of cccDNA levels (Sung et al., 2005). Thus, all therapies in the treatment of HBV should be benchmarked against HBsAg loss, as a marker of drug utility and efficacy.

There is now concensus amongst the major liver disease authorities in terms of their clinical practice guidelines and the recommended agents available for the treatment of chronic HBV infection. Treatment strategies have broadened and include the potent oral antiviral agents tenofovir (Marcellin et al., 2008; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2009) and entecavir (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2008) as first-line monotherapies. While these two agents have emerged as the leading oral antivirals, the weaker and more outdated agents such as telbivudine, lamivudine and adefovir are still widely used. The use of lamivudine or adefovir as monotherapy is no longer recommended and should be avoided if at all possible, owing to the high rates of resistance reported with these drugs. Pegylated interferon (peginterferon) alfa-2a has re-emerged as a viable alternative to oral antiviral agents in the treatment of chronic HBV. This is due primarily to its potent immunomodulatory effects which gives it a clear advantage over oral antivirals. Significant rates of surface antigen (sAg) loss have been reported in both HBeAg positive and negative disease and the inclusion of surface antigen quantification has provided an objective tool to assess response to pegylated interferon. The advantages of interferon therapy, such as a finite treatment course, good rates of surface antigen loss in selected patients, must be weighed against the disadvantages associated with an injection-based therapy and the inherent side effect profile associated with interferons. Therefore, a careful and rational approach must be followed when considering treatment of chronic HBV. While reported rates of resistance is extremely low with entecavir, and none reported with tenofovir, the treatment landscape for chronic HBV has changed dramatically from the high rates of resistance previously seen with lamivudine and adefovir. However, when commencing oral antiviral agents, the patient must be aware they are potentially embarking on a lifelong course of treatment.

Hepatitis C

Pegylated interferon and ribavirin combination therapy are now the standard care of chronic HCV (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2010). The SVR for treatment of naïve patients is of the order of 55% for genotypes 1 and 4 (48 weeks of therapy) and 80–85% for genotypes 2 and 3 (24 weeks of therapy). The treatment duration, however, can be individualised based on the baseline viral load and the speed of virological response during treatment. Patients failing to achieve a significant reduction in viral load after 12 weeks will normally have therapy discontinued. The current standard of care combination therapy is limited by the side effect profile, complications of therapy and poor patient tolerability. Side effects of therapy include influenza-like symptoms, decrease in haematological parameters (haemoglobin, neutrophils, white blood cell count and platelets), gastro-intestinal complaints, psychiatric disturbances (anxiety and depression) and hypo- or hyperthyrodism. It is accepted that these side effects are a major obstacle preventing completion of therapy by hindering compliance or enforcing significant dose reductions. While growth factors (erythropoietin, GCSF) and antidepressants may alleviate some side effects, there remains a clear need for better treatment strategies in chronic HCV infection.

Wilson’s disease

Case 16.1

| Na | 124 (133–143 mmol/L) |

| K | 3.0 (3.5–5.0 mmol/L) |

| Creatinine | 131 (80–124 μmol/L) |

| Urea | 14.3 (2.7–7.7 mmol/L) |

| Bilirubin | 167 (3.15 μmol/L) |

| ALT | 24 (0–35 IU/L) |

| PT | 18.9 (13 s) |

| Albumin | 24 (35–50 g/dL) |

| Hb | 8.9 (13.5–18 g/dL) |

Questions

Answers

Case 16.2

| Na | 116 | (133–143 mmol/L) |

| K | 3.8 | (3.5–5 mmol/L) |

| Urea | 8.5 | (3.3–7.7 mmol/L) |

| Cr | 119 | (80–124 μmol/L) |

| Bilirubin | 459 | (3–17 μmol/L) |

| Albumin | 23 | (35–50 g/L) |

| ALT | 23 | (0–35 iu/L) |

| Alk P | 524 | (70–300 iu/L) |

| PT | 18.6 | (13 s) |

Drugs on admission are as follows:

Answers

Bass N.M., Mullen K.D., Sanyal A., et al. Rifaximin treatment in hepatic encephalopathy. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2010;362:1071-1081.

Marcellin P., Heathcote E.J., Buti M., et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus adefovir dipivoxil for chronic hepatitis B. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2008;359:2442-2455.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Entecavir for the Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis B, Technology Appraisal 153.. London: NICE. 2008. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/TA153

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Tenofovir Disoproxil for the Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis B, Technology Appraisal 173. London: NICE. 2009. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/TA173

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Peginterferon Alfa and Ribavirin for the Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C, Technology Appraisal 200. London: NICE. 2010. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA200

Sung J.J., Wong M.L., Bowden S., et al. Intrahepatic hepatitis B virus covalently closed circular DNA can be a predictor of sustained response to therapy. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1890-1897.

Foster G., Reddy K.R., editors. Clinical Dilemmas in Viral Liver Disease. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2010.

Friedman L.S., Keeffe E.B., editors. Handbook of Liver Disease, second ed., London: Elsevier Health, 2004.

Lindor K.D., Talwalkar J.A. Cholestatic Liver Disease. New Jersey: Humana Press; 2008.

Mahl T.E., O’Grady J. Fast Facts: Liver Disorders, (Fast Facts series).. Oxford: Health Press Limited. 2006.