Liver and Lung Trematodes

1. List the clinically significant trematodes capable of infecting the liver and lungs.

2. Describe the general life cycle of the liver and lung flukes and identify the infective stage for humans.

3. Describe the diagnostic methods used to identify the liver and lung flukes including the microscopic differentiation of eggs and serologic methods.

4. Describe the pathogenesis of the liver and lung flukes including location and associated disease manifestations.

5. List the drug of choice for infections with liver and lung flukes.

6. Describe the transmission of the liver and lung flukes and discuss how infection may be prevented.

The Liver Flukes

General Characteristics

Epidemiology and Life Cycle

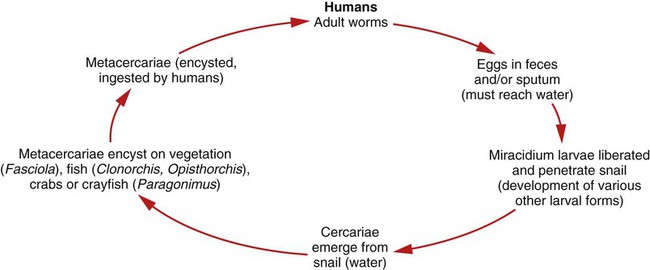

The life cycle of the liver flukes is very similar to that of the intestinal flukes. The adult worms produce eggs in the biliary ducts that are then excreted from the body in the feces. The free-swimming miracidium is released from the egg in freshwater and enters the snail host where it develops into a redia and then a cercariae, which leaves the snail and enters the water (Figure 57-1). The cercariae of Clonorchis and Opisthorchis are ingested by a second intermediate host, a freshwater fish. The cercariae then encyst and develop into the metacercariae within the intermediate host. The metacercaria is the infective stage for humans. When infected freshwater fish are eaten raw or undercooked, the metacercariae will excyst in the duodenum and then travel to the bile duct where they mature. The cercariae of Fasciola encyst on freshwater vegetation, such as watercress and water chestnuts, and develop into metacercariae. When the infected vegetation is eaten raw, the metacercariae will excyst in the duodenum and then travel to the bile duct and mature. Figure 57-2 depicts the general life cycles of the liver and lung flukes.

Laboratory Diagnosis

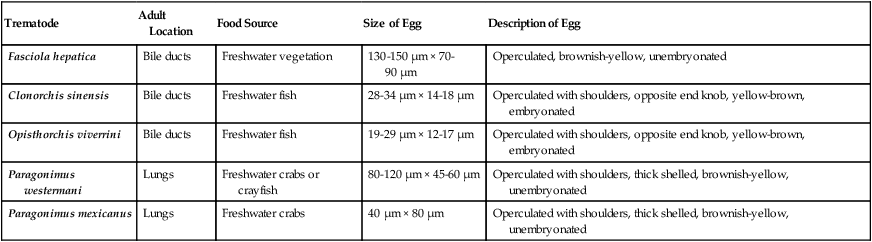

Identification of the liver flukes is primarily made by recovery of the eggs in feces using a sedimentation method and a wet mount with or without iodine staining. Table 57-1 shows some diagnostic characteristics of the liver and lung flukes.

TABLE 57-1

Characteristics of Liver and Lung Trematodes

| Trematode | Adult Location | Food Source | Size of Egg | Description of Egg |

| Fasciola hepatica | Bile ducts | Freshwater vegetation | 130-150 µm × 70-90 µm | Operculated, brownish-yellow, unembryonated |

| Clonorchis sinensis | Bile ducts | Freshwater fish | 28-34 µm × 14-18 µm | Operculated with shoulders, opposite end knob, yellow-brown, embryonated |

| Opisthorchis viverrini | Bile ducts | Freshwater fish | 19-29 µm × 12-17 µm | Operculated with shoulders, opposite end knob, yellow-brown, embryonated |

| Paragonimus westermani | Lungs | Freshwater crabs or crayfish | 80-120 µm × 45-60 µm | Operculated with shoulders, thick shelled, brownish-yellow, unembryonated |

| Paragonimus mexicanus | Lungs | Freshwater crabs | 40 µm × 80 µm | Operculated with shoulders, thick shelled, brownish-yellow, unembryonated |

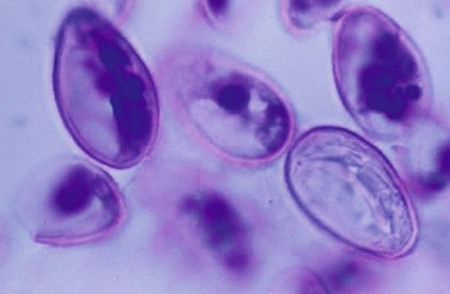

The adult worms of Clonorchis are elongated and narrow, and a transparent reddish-yellow color. Adult Clonorchis may vary in size from 10 to 25 mm × 3 to 5 mm. The eggs of Clonorchis are 28 to 30 µm × 14 to 18 µm. The eggs have shouldered opercula and a small knob at the end opposite the operculum, are yellow-brown in color, and are embryonated when they leave the body (Figure 57-3).

Like Clonorchis, the adult worms of Opisthorchis are elongated and narrow, and a transparent reddish-yellow color. Adult worms of Opisthorchis, however, are much smaller in size: 5 to 10 mm × 0.8 to 1.9 mm. The size of Opisthorchis eggs is slightly smaller than those of Clonorchis; Opisthorchis eggs are 19 to 29 µm × 12 to 17 µm. Also like Clonorchis, the eggs have shouldered opercula and a small knob at the end opposite the operculum, are yellow-brown in color, and are embryonated when they leave the body (see Figure 57-3).

The adult worm of Fasciola is much larger (2 to 5 cm × 0.8 to 1.3 cm), with a cephalic cone at the anterior end that contains the oral sucker. The eggs are 130 to 150 µm × 70 to 90 µm, operculated, brownish-yellow, and unembryonated when they leave the body. Because the eggs of Fasciola and Fasciolopsis are virtually indistinguishable, it may also be necessary to recover eggs from bile specimens, or to recover adult worms. Definitive identification of Fasciola is important because the treatment is different than that for Fasciolopsis. There is also serologic testing available in the United States for diagnosis of Fasciola. Enzyme immunoassay (EIA) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) serum IgG antibody testing is performed at private references laboratories; cross reactivity with other trematodes, such as the schistosomes, may be an issue. Figure 56-3 shows the eggs of Fasciola hepatica, and Figure 56-2 is a Fasciolopsis buski adult fluke.

The Lung Flukes

General Characteristics

Epidemiology and Life Cycle

The adult worms, encapsulated in the lungs, produce eggs that leave the lung via the bronchioles, stimulating a cough response. The eggs are then swallowed and eventually excreted in the feces.* The free-swimming miracidium is released from the egg in freshwater and enters the snail host where it develops into a redia and then a cercariae, which leaves the snail and enters the water. The cercariae then enter a second intermediate host, a crab or crayfish, where they encyst and develop into metacercariae. The metacercaria is the infective stage for humans. When infected freshwater crabs and crayfish are eaten raw or undercooked, the metacercariae will excyst in the duodenum and then migrate through the intestinal wall, and eventually through the diaphragm and into the lungs where they encapsulate (usually in pairs) and mature (see Figure 57-2).

Laboratory Diagnosis

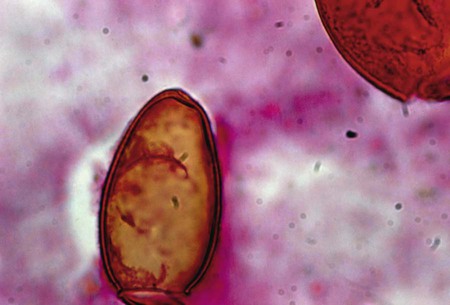

Paragonimus eggs (see Table 57-1) may be recovered from sputum, and occasionally in feces using a sedimentation concentration method. The eggs may be observed in a wet mount (with/without iodine stain) (Figure 57-4). Charcot-Leyden crystals may also be observed in sputum or lung tissue specimens. Charcot-Leyden crystals are slender and pointed at both ends. The crystals normally appear colorless and stain purplish to red with trichrome. Elevated levels of eosinophils in whole blood and elevated IgE levels in serum may be present. Lesions in the lungs may be observed in x-ray. There is also serologic testing available in the United States for diagnosis of P. westermani. The Division of Parasitic Disease at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) performs serum IgG EIA and immunoblot testing, and EIA serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) IgG antibody testing is performed at private reference laboratories; cross reactivity with other species and trematodes may occur.