Chapter 351 Liver Abscess

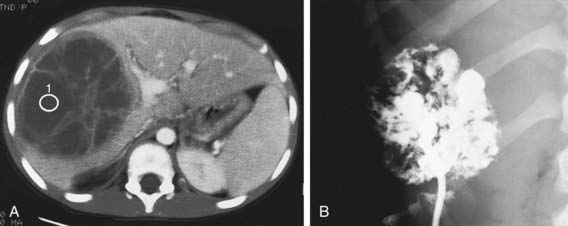

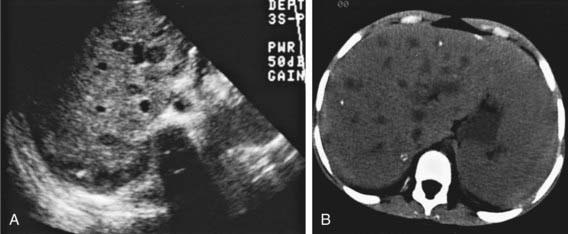

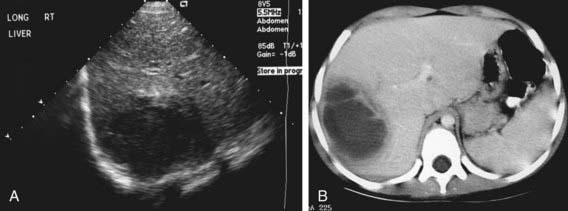

Signs and symptoms are nonspecific and can include fever, chills, night sweats, malaise, fatigue, nausea, abdominal pain with right upper quadrant tenderness, and hepatomegaly; jaundice is uncommon. Diagnosis can be challenging and is often delayed; a high index of suspicion is necessary in children with risk factors. Serum aminotransferase and more often the alkaline phosphatase levels are elevated. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate is high, and leukocytosis is common. The results of blood cultures are positive in 50% of patients. Chest x-rays might show elevation of the right hemidiaphragm with decreased mobility or a right pleural effusion. Ultrasound or CT can confirm diagnosis (Figs. 351-1 to 351-3). Solitary liver abscesses (70% of cases) in the right lobe of the liver (75% of cases) are more common than multiple abscesses or solitary left lobe abscesses.

Fung CP, Change SC, Hu BS, et al. A global emerging disease of Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: is serotype K1 an important factor for complicated endopthalmitis? Gut. 2002;50:420-424.

Kaplan GG, Gregson DB, Laupland KB. Population-based study of the epidemiology of and the risk factors for pyogenic liver abscess. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:1032-1038.

Kumar A, Srinivasan S, Sharma AK. Pyogenic liver abscess in children—South Indian experiences. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:417-421.

Margalit M, Elinav H, Ilan Y, et al. Liver abscess in inflammatory bowel disease: report of two cases and review of the literature. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:1338-1342.

Pereira FE, Musso C, Castelo JS. Pathology of pyogenic liver abscess in children. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 1999;2:537-543.

Pineiro-Carrero VM, Andres JM. Morbidity and mortality in children with pyogenic liver abscess. Am J Dis Child. 1989;143:1424-1427.