84

Lipodystrophies

Key Points

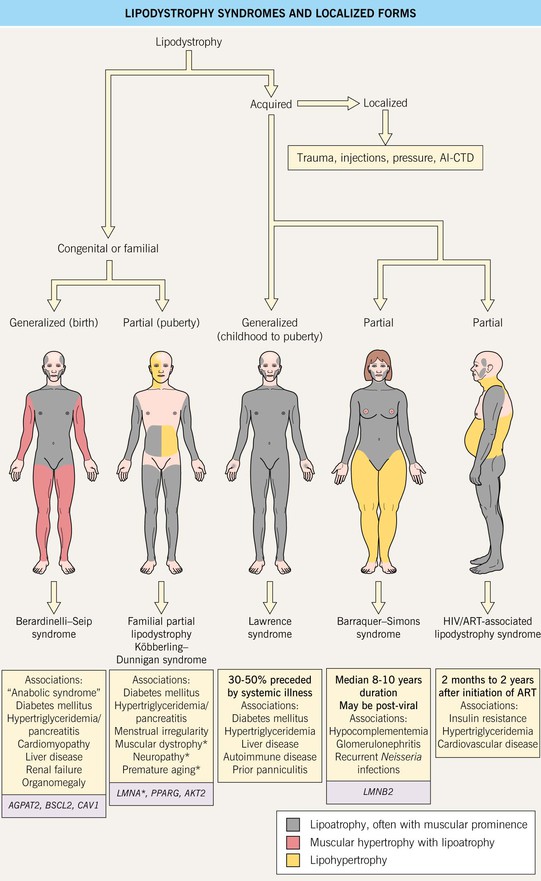

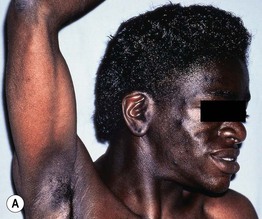

• Lipodystrophy is characterized by areas of fat loss/absence (lipoatrophy), and/or fat accumulation (lipohypertrophy), with both often coexisting in the same patient; lipoatrophy can lead to the appearance of muscular hypertrophy (Fig. 84.1).

Fig. 84.1 Lipoatrophy of the lower extremities, leading to the appearance of muscular hypertrophy. Courtesy, William D. James, MD.

• Lipoatrophy may be classified as.

– Generalized, partial, or localized (Fig. 84.2).

Fig. 84.2 Lipodystrophy syndromes and localized forms. Shaded boxes include best-described underlying genetic mutations. In familial partial lipodystrophy, LMNA mutations are associated with facial lipohypertrophy and abdominal lipoatrophy while PPARG mutations are associated with abdominal lipohypertrophy.

– Inherited (often appears during childhood) or acquired.

• Localized lipoatrophy may be idiopathic or secondary to various causes, e.g. injection of medications (in particular CS), pressure (Fig. 84.3), trauma, autoimmune connective tissue disease (e.g. lupus panniculitis; Fig. 84.4), and other panniculitides due to inflammation or lymphoma.

Fig. 84.3 Localized lipoatrophy of the upper lateral calf. A common finding in women due to crossing the legs while seated. Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

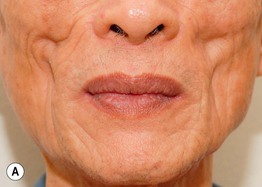

Fig. 84.4 Lipoatrophy secondary to lupus panniculitis. A An area of depression on the cheek due to burnt-out lupus panniculitis; note the dyspigmentation and scarring from an overlapping lesion of discoid lupus erythematosus. B Circular depressions on the upper arm, a common location for lupus panniculitis. Lipoatrophy can be seen with other connective tissue disorders, including dermatomyositis in children. A, Courtesy National Skin Centre, Singapore.

• Localized lipohypertrophy is most commonly seen in the setting of multiple insulin injections.

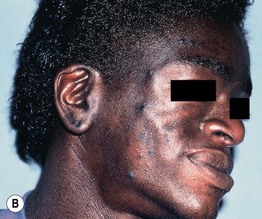

• Human immunodeficiency virus/antiretroviral therapy (HIV/ART) causes a distinct syndrome of central lipohypertrophy and peripheral lipoatrophy (Figs. 84.5 and 84.6).

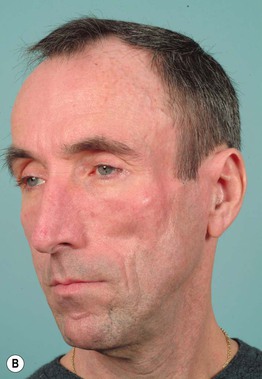

Fig. 84.5 HIV/ART-associated lipodystrophy. A There is symmetric loss of buccal, parotid, and preauricular (Bichat’s) fat pads, resulting in prominent zygomata, sunken eyeballs, and a cachectic appearance. B The side view highlights the loss of temporal fat. In particular, stavudine and protease inhibitors are most strongly associated with lipoatrophy. Courtesy, Ken Katz, MD.

Fig. 84.6 HIV/ART-associated lipodystrophy. A Marked indentation of the medial cheeks in an older patient, with redundant melolabial folds. B Lower extremities with prominent veins and defined musculature. A, Courtesy, Priya Sen, MD; B, Courtesy, Alison Sharpe Avram, MD and Matthew Avram, MD.

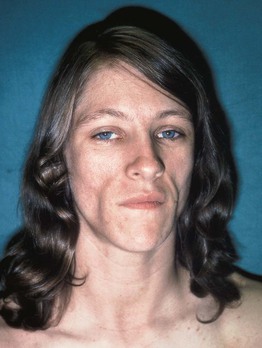

• Extensive lipodystrophy syndromes have characteristic distributions of fat atrophy and hypertrophy (Figs. 84.2 and 84.7–84.9).

Fig. 84.7 Congenital generalized lipodystrophy. A Extensive acanthosis nigricans, facial and extremity lipodystrophy, and muscular habitus. B Close-up view demonstrating loss of Bichat’s fat pad and buccal fat. A, B, Courtesy, Kenneth E. Greer, MD.

Fig. 84.8 Acquired generalized lipodystrophy. There is loss of subcutaneous fat, resulting in a muscular appearance of the legs and accentuation of the tendons. Courtesy, Jacqueline Junkins-Hopkins, MD.

Fig. 84.9 Acquired partial lipodystrophy in a patient with nephritic factor and renal disease. Lipoatrophic features are most prominent on the face, with a marked loss of buccal fat. Axillary acanthosis nigricans was present. Courtesy, Kenneth E. Greer, MD.

• Other associations include hormonal abnormalities, anabolic syndrome, glomerulonephritis.

• Rx: depends in part on underlying etiology (see Fig. 84.2); (1) remove inciting cause (e.g. relieve pressure or rotate sites of injections); (2) address the metabolic syndrome if present; (3) improve cosmetic appearance (e.g. injection of poly-L-lactic acid or autologous fat transfer into the cheeks).

For further information see Ch. 101. From Dermatology, Third Edition.