CHAPTER 72 Lip augmentation

History

With the FDA approval of the first hyaluronic acid (HA) preparation for soft tissue augmentation in 2004, this opened the door to a new generation of injectable dermal fillers. The hyaluronic acid products have proved exciting materials which work superbly in soft tissue augmentation. HAs are a naturally occurring polysaccharide found in the dermis and through the cross-linking process, a greater tissue residence time has resulted. As injectors refine their techniques and as manufacturers work on better cross-linking materials and techniques, these agents have proved superior to bovine collagen and in the right hands with the best technique, we routinely obtain lasting results which approach and in some cases exceed one year.

Physical evaluation

• Evaluate general health and medical condition of your patient.

• Take photographs for before and after comparison.

• Assess whether or not your patient has undergone prior lip augmentation procedures and if so, which injectable fillers were used. This is critical to a good outcome.

• Discuss with your patient what she or he expects from the procedure. Many patients have unrealistic expectations of lip augmentation and as a result will not be entirely pleased with the result.

• Examine the degree of structural/bony loss the patient has experienced and the degree of volume lost in the lips. This will help determine how much filler you will need and how much you will need to rebuild the support in the lower third of the face.

• Explain to your patient what your plan is for their procedure, what you recommend and what they should expect. This is generally where we explain to some patients that contrary to what they may have been told or have seen, it is not appropriate to inject large amounts of filling material into the lips as this will not provide an aesthetically pleasing result. We explain that there is more to lip augmentation than just injecting volume into the lips; we must also rebuild structural support on which the lips sit.

• Pain is always a significant concern to our patients and lip augmentation can be a painful procedure if not done properly. Take the time to reassure the patient that you will take certain steps and explain what they are so they will not experience pain.

• Discuss with your patient postoperative expectations from ice application, use of pain relievers, the possibility of bruising, and temporary distortion due to swelling. Most patients expect that they will have the final result the minute the procedure is completed and many do, but educating the patient is critical.

Anatomy and architecture of the lip

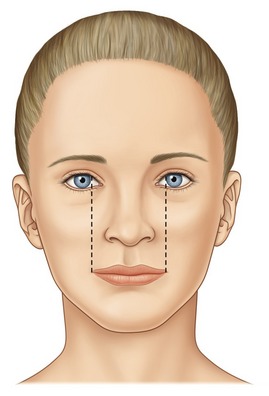

Are there specific considerations that can be established for lip augmentation? In looking at the aging lip, there are two important factors that one should consider. One is the shape of the lips themselves and the other is the importance of the support provided to the lower third of the face by bony structures and the teeth. These are all features dependent upon not only injection of the lips themselves, but also on the volumetric restoration of the lower third of the face. The lips should be full and well-defined. They should be injected without blunting the edge of the vermilion border of the upper lip, which if not done precisely will give a flat simian quality to the upper lip. The injector must also focus on the restoration of the ends of the lips or oral commissures, as well as the building of buttresses at these ends to restore proper height to the lips and lower third of the face; correcting the labio-mandibular grooves/oral commissures. While dermatologic and aesthetic journals deal with substances for implantation, these journals have not, in themselves, held good information dealing with the proper concepts of lip augmentation. Instead, we have found this information in the dental literature where a number of articles have discussed in great detail the proper lip height, size, and location of the lips as produced by dental restoration. The following are some criteria for evaluating the aesthetic lip in the well-proportioned face. The length of the closed, relaxed mouth should equal the distance between the medial aspect of the irises. The ratio of the mucosa show of the upper to lower lips should be 1 : 1.6 (Fig. 72.1).

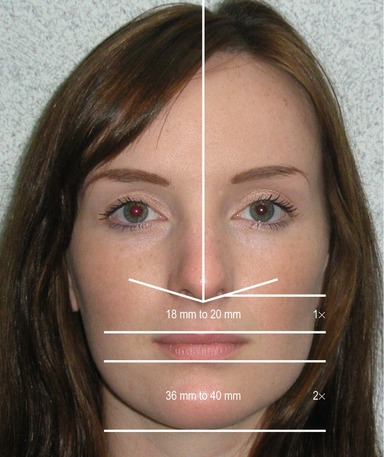

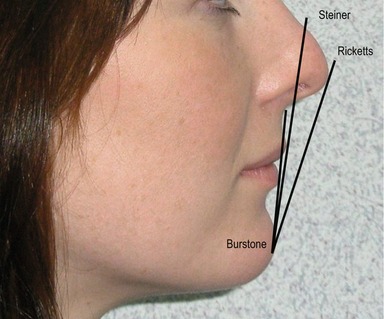

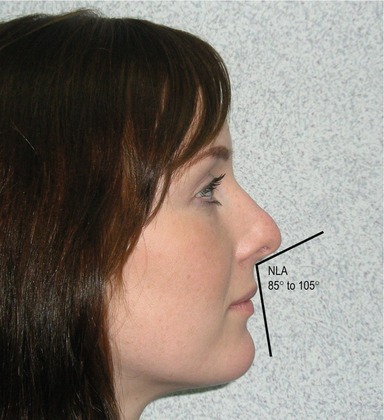

The inter-pupillary line and commissural line should be parallel when the mouth is relaxed (Fig. 72.2). The distance from the base of the nose to the upper lip should be 18–20 mm and the distance from the lower lip to the point of the chin should be 36–40 mm (Fig. 72.3). These distances change as the face ages and need to be restored. A line from the midpoint of the nose to the chin (Steiner line) should touch the upper lip (Fig. 72.4). The nasolabial angle should range from approximately 84–105 degrees (Fig. 72.5). The most important aspect of lip augmentation involves restoring the ends of the lip and building buttresses at the ends to restore the height loss. This also corrects the labio-mandibular grooves. It is important to inject the lips so as to maintain the ski-jump edge (the Glogau–Klein point) of the upper lip (Fig. 72.6). Oftentimes, using a combination of products can result in an improved aesthetic result. It is important to balance the treatment by refilling lost space in the nasolabial folds, as well as the lower third of the face. Lips must maintain a natural profile. Unnatural fullness above the lip is to be avoided at all costs since it blunts the edge of the lip and gives them a prognathic appearance. With respect to the facial profile, the nasolabial angle should be 85 to 105 degrees (Fig. 72.3). Finally, there is a slight elevation or ski-jump, which is a point of inflection as the lip turns from glabrous skin to mucosa. This site had not been formally noted in the scientific literature previously, therefore, it is referred to as the G-K (Glogau–Klein) point.

Fig. 72.2 The interpupillary line and commissural line should be parallel when the mouth is relaxed.

Technical steps

The patient is injected from right to center and then from left to center (Fig. 72.7). The preservation of the cupid’s bow is critical because it is the defining aesthetic of the upper lip. Furthermore, the lower lip is to be injected not as a rounded wheel mass, but instead to produce central rollout or pout. When the lip is injected, the physician must stretch the lip to assure themselves that they are beginning at the end of the lip that is now part of the labio-mandibular groove (Fig. 72.8). Furthermore, with a firm surface to inject against, the stretched lip provides a better flow surface.

The tip of the needle should be inserted into the potential vermilion space at a 45-degree angle on the mucosal side. The needle is then redirected at a 20 degree angle from the lip. With the lip stretched, this will allow the material to flow along the potential space. Injection must be slow to ensure that the material stays uniform within this tubular potential. Again, adequate stretch of the lip is critical because a firm surface improves the volume uniformity of flow of the material, which can be hampered by the high viscosity of the agent. The finger can be kept at the G-K point to ensure flow within the channel.

Flow out of or flow above the channel can create an elevated lump, while flow below the channel is also to be avoided. As a point of resistance is met where the material will not flow, the continuation of the injection is moved to the next point. This technique, which was developed by the primary author, is referred to as the Klein anterior flow technique or serial puncture technique. Once the material is injected past the midline of the lower lip, this section of the lip is complete. Next, the portion of the lip that connects the lower lip to the upper lip along the side of the mouth is addressed (the Klein space). This will lift the lip and decrease the labio-mandibular groove. One may wonder how this elevates the corner of the mouth. Theoretically, this is accomplished because the material flows around the modeolus and securely elevates the corner of the upper and lower lip. The upper lip is injected in a similar manner, paying particular attention to retaining the shape of the cupid’s bow. Again, care must be taken to keep the material in the proper channel avoiding a lump above the lip. Once this is complete, supportive buttresses from the jaw to the lip are injected in a sequential manner to support the lips and re-establish the vertical height, which has been lost as previously noted to bone resorption and any dental changes that may have occurred (Fig. 72.9). While there are other techniques for lip augmentation, it the belief of the authors (and the literature supports this) that this technique provides for the fewest possible adverse events. It is our hope that this framework will provide the basis for lip augmentation.

Complications

Pearls & pitfalls

Pearls

• Critical to a good outcome is assessment of whether or not the patient has undergone prior lip augmentation procedures and if so, which injectable fillers were used.

• There is more to lip augmentation than just injecting volume into the lips; you must also rebuild support on which the lips sit.

• The length of the closed, relaxed mouth should equal the distance between the medial aspect of the irises.

• The ratio of the mucosa show of the upper to lower lips should be 1 : 1.6.

• It is important to inject the lips so as to maintain the ski-jump edge (the Glogau–Klein point) of the upper lip.

Pitfalls

• Take time to adequately prepare patients for realistic outcome.

• Take sufficient time to assess the lips and their dimensions.

• Take time to inject slowly, carefully and deliberately.

• Use caution not to over-augment lips.

• Use care in maintaining natural curve, G-K point and do not fill above the vermilion border on the upper lip to maintain sharp border.

Summary of steps

1. Prior to injection, suitable anesthesia should be administered.

2. Without the use of a dental block (these are not recommended), a very gentle injection technique is required.

3. After application of a topical anesthetic agent, we mix 10 mL of 1% lidocaine with epinephrine to the HA product.

4. The patient is injected from right to center and then from left to center.

5. Injection must be slow to ensure that the material stays uniform within this tubular potential.

6. Adequate stretch of the lip is critical because a firm surface improves the volume uniformity of flow of the material.

7. The finger can be kept at the G-K point to ensure flow within the channel.

8. Care must be taken to keep the material in the proper channel avoiding a lump above the lip.

9. Once the material is injected past the midline of the lower lip, this section of the lip is complete. Next, the portion of the lip that connects the lower lip to the upper lip along the side of the mouth is addressed (the Klein space).

10. The upper lip is injected in a similar manner paying particular attention to retaining the shape of the cupid’s bow.

11. Once this is complete, supportive buttresses from the jaw to the lip are injected in a sequential manner to support the lips and re-establish the vertical height.

Carruthers J, Klein A, Carruthers A, Glogau R, Canfield D. Safety and efficacy of non-animal stabilized hyaluronic acid for improvement of mouth and lip corners. Dermatol Surg. 2005:227–231.

Cheng JT, Perkins SW, Hamilton MM. Perioral rejuvenation. Facial Plast Surg. 2000;8(2):223–233.

Elson ML. Anesthesia for lip augmentation. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23(5):405.

Etcoff N. Survival of the prettiest: The science of beauty. New York: Doubleday; 1999.

Friedman P, et al. Safety data of injectable non-animal stabilized hyaluronic acid gel for soft tissue augmentation. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:491–494.

Guerrissi JO. Surgical treatment of the senile upper lip. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106(4):938–940.

Klein AW. Tissue augmentation in clinical practice, 2nd edn. London: Taylor and Francis; 2006.

Klein AW. In search of the perfect lip. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31(11):1599–1603.

Maloney BP. Cosmetic surgery of the lips. Facial Plast Surg. 1996;12(3):265–278.

Niamtu J. Cosmetic oral and maxillofacial surgery: the frame for cosmetic dentistry. Dent Today. 2001;20(4):88–91.