CHAPTER 54 Linked Total Elbow Arthroplasty in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis

INTRODUCTION

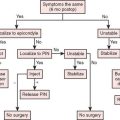

Both coupled and uncoupled elbow replacement prosthetic designs are employed for the management of end-stage rheumatoid arthritis.11,12,43 This chapter reviews the results of the linked, semiconstrained design, primarily that of the Coonrad/Morrey. As noted previously in this text, the clinical and radiologic presentation of inflammatory arthritis in general and rheumatoid arthritis in particular varies considerably (Fig. 54-1). The semiconstrained implant is especially useful in the type III and IV presentations because this design philosophy assesses stability in the face of bone loss and joint laxity2 (Fig 54-2).

FIGURE 54-1 The spectrum of radiographic presentation from grades I to V in patients with rheumatoid arthritis after Connor and Morrey9 and Morrey.33

To date, several evaluation systems exist that allow a critical assessment of the elbow when affected by disease and after therapeutic intervention (see Chapter 5). In the past, we employed the Mayo Elbow Performance Score (MEPS) as defined in Table 54-126 and are currently incorporating the measurements of the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) questionnaire as well.

| Function | Point Score |

|---|---|

| Pain (45 points) | |

| None | 45 |

| Mild | 30 |

| Moderate | 15 |

| Severe | 0 |

| Motion (20 points) | |

| Arc 100 degrees | 20 |

| Arc 50 to 100 degrees | 15 |

| Arc 2 degrees | 5 |

| Stability (10 points)† | |

| Stable | 10 |

| Moderate instability | |

| Gross instability | 0 |

| Daily function (25 points) | |

| Combing hair | 5 |

| Feeding oneself | 5 |

| Hygiene | 5 |

| Putting on shirt | 5 |

| Putting on shoes | 5 |

| Maximum possible total | 100 |

* 90 points or more = excellent; 75 to 89 points = good; 60 to 74 points = fair; and less than 60 points = poor.

† Stable = no apparent varus-valgus laxity clinically; moderate instability = less than 10 degrees of varus-valgus laxity; gross instability = 10 degrees or more of varus-valgus laxity.

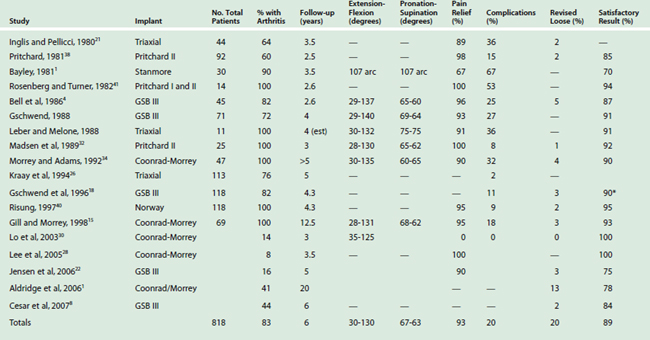

Review of the literature reveals improving and encouraging results with several semiconstrained designs (Table 54-2).16 In this chapter, we review several of these experiences and then focus on Mayo’s perspective and outcomes. The outcome of replacement for rheumatoid is superior to that for traumatic arthritis.3

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

THE PRITCHARD PROSTHESIS

The Pritchard II prosthesis (Fig. 54-3) was an early design introduced in the 1970s as a linked semiconstrained device.32,38,39 Pritchard’s own experience with 92 patients was reported in 1981 and included 55 with rheumatoid arthritis. The mean follow-up was short (2.5 years). Although the range of motion, stability, and measure of function were not reported, relief of pain was reported as 98%.38 A 15% complication rate and 2% loosening requiring revision were recorded.

Subsequently, Madsen and associates32 followed 25 consecutive Pritchard II implants for a mean of 3 years. Twenty-three of 25 patients had relief of pain. The flexion arc averaged 28 to 130 degrees and pronation-supination was 65 to 62 degrees, respectively. Stability was not discussed, but the mean assessment score improved from 40 to 82. However, radiographic loosening occurred in 6 of 24 elbows, and two necessitated revision.

These initial reports of the Pritchard II implant were of small numbers, and their findings were regarded as preliminary.32,38,39 The major problem was wear or fracture of the polyethylene bearing. The device was subsequently modified but is not used to any extent today.

THE TRIAXIAL DEVICE

There has been a tendency for wear and dislocation over time; however,13 this articulation has undergone numerous modifications but still allows several degrees of varus-valgus and axial rotation “play” (Fig. 54-4). The implant has been used almost exclusively for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. A customized version has been described for various pathologic states other than rheumatoid arthritis.

RESULTS

In the past, several reports emanating from the designing institution have documented the use of several variations of this design for rheumatoid arthritis. In general, a 90% satisfactory result is reported with follow-up less than 5 years.21 In one large series, Kraay and associates26 reviewed the outcome of 113 patients. Of these, 86 had rheumatoid arthritis. With surveillance averaging 5 years, five devices had failed owing to sepsis, but only two had been revised because of aseptic loosening. The 3- and 5-year survival rates were 92% and 90%, respectively, but the outcome has subsequently deteriorated owing to instability occurring when the bushing wore.

GSB III PROSTHESIS

The current GSB II device provides about 4 degrees of varus-valgus toggle and uniquely some axial translation (Fig. 54-5). The stem is stabilized by medial and lateral flanges that are attached to the condyles. Hence, a requirement of this implant is intact or reconstructed condyles. Experience with the modified implant was reported by Bell and colleagues4 in 1986. Forty-one of 46 patients had relief of pain, and range of motion averaged 29 to 137 degrees. In 1988, Gschwend and associates17 updated this experience, with the majority of patients having rheumatoid arthritis. Fifty-three of 57 patients had relief of pain; extension-flexion improved from 29 to 140 degrees, with pronation-supination increasing 68 to 64 degrees, respectively. In five elbows, there was a nonprogressive radiolucency. Overall, 27% of the elbows had complications, including four requiring excision arthroplasty. Seven elbows disarticulated during follow-up.

Later Gschwend et al18 focused on the late complications of 118 GSB III implants in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, with a mean surveillance time of 4.3 years. The complication rate was only 11%, with a revision rate of 8.4%. The most common complication in rheumatoid patients was radiographic loosening in 3.4% (clinical, 2.8%), infection in 2.8%, and disarticulation in 2.5%. Instability did not occur. More recently, Cesar et al8 reported satisfactory results in 84% of 44 patients followed a mean of 6 years. Similarly Jensen et al22 observed 85% favorable results at 5 years. These outcomes have been reproduced by others with similar samples and comparable periods of surveillance.

COONRAD-MORREY TOTAL ELBOW ARTHROPLASTY

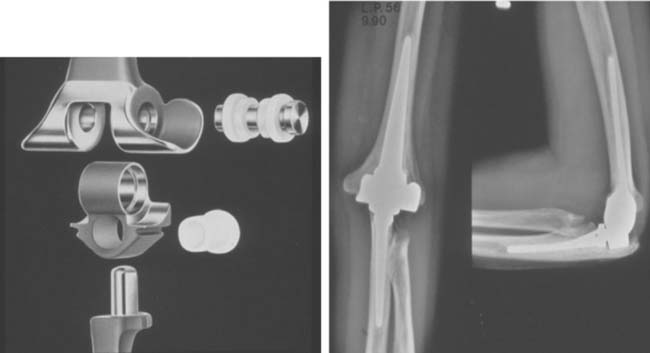

The original Coonrad-Morrey design, used since 1971, was modified in 1978 to allow 7 degrees of varus-valgus motion and 7 degrees of axial rotation (see Chapter 51). In 1981, an anterior flange and plasma spray were added to the humeral component (Fig. 54-6).32,33 The plasma spray was replaced with sintered beads in 1985, and in 1993, the beads were replaced with a polymethyl methacrylate precoat on the ulna (Table 54-3). This design has emerged as a popular implant for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.15,20 In Coonrad’s career experience with 41 joints followed from 10 to 31 years, at final assessment, there were no resections and all were functional joints, although many had been revised for various reasons.1 In contrast, a limited experience from Singapore of just seven implants for rheumatoid arthritis revealed that six (86%) were satisfactory at 2.5 years.27 A clinical experience with 14 replacements for rheumatoid arthritis documented a satisfactory outcome in 97% at 3 years.30

TABLE 54-3 Modifications of the Original Coonrad-Morrey Total Elbow Arthroplasty

| Implant | Modification | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Coonrad III (Mayo modified) | Loose hinge “semi-constrained” | 1978 |

| Coonrad-Morrey | Flange Plasma spray | 1981 |

| Beaded surface | 1984 | |

| Precoat ulna | 1991 | |

| Co-Cr pin | 1993 |

Co-Cr, cobalt-chromium.

MAYO EXPERIENCE

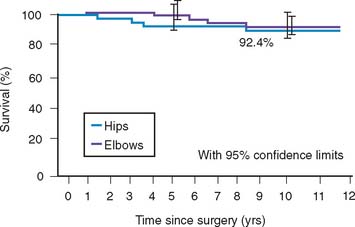

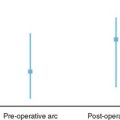

An initial report detailed experience with the Coonrad-Morrey device documented outcomes of 58 consecutive implants with a mean surveillance time of 3.8 years; 53 patients (91%) had relief of pain (Fig. 54-7). The functional component of the MEPS improved from 8 to 23, and overall, the score increased from 38 to 94. There were no aseptic loosening, and reoperations occurred in six elbows (10%).34 Subsequently, more recently, the results of the first 78 consecutive Coonrad-Morrey total elbow arthroplasties with at least 10 years’ and up to 20 years’ surveillance has been reported15 (Fig. 54-8). This group included 69 patients with rheumatoid arthritis, three with a distal humeral nonunion, and 12 with a previous total elbow arthroplasty of another design that failed because of aseptic loosening. Of the 78 patients, 76 (97%) reported relief of pain. Mean extension-flexion was 28 to 131 degrees, representing a 12-degree increase. Mean pronation was 68 degrees and supination was 62 degrees, an increased arc of 22 degrees. The MEPS preoperatively was 42 but increased to 87 at final review. The minimum 10-year objective (MEPS) outcome for the Coonrad-Morrey total elbow arthroplasty was 67 of 78 good/excellent (86%) and 11 (14%) fair/poor (see Fig. 54-8). The 5-year survival rate was 94.4% (95 percent confidence interval [CI], 89% to 99%) and the 10-year rate was 92.4% (95% CI, 85% to 99.1%) (Fig. 54-9).

Radiographic analysis was undertaken in 76 of 78 elbows. More than 90% had a well-incorporated bone graft (Fig. 54-10). Loosening was defined as a progressive radiolucency greater than 2 mm that was completely circumferential about the prosthesis. One humeral and three ulnar components were radiographically loose, and two had been revised. Three of 76 elbows (3.9%) had complete bushing wear, and 6 (7.9%) had partial wear (Fig. 54-11). Of note, only limited osteolysis occurred, even with extensive bushing wear, but some resorption does occur.

During the 10 to 15 years after implantation, 10 of the 78 patients (12.8%) required reoperation for reasons summarized in Table 54-4 (see Chapters 65 and 66). King and associates25 have reported the Mayo experience with revision elbow replacement surgery. This experience is summarized in Chapters 65 and 66. Overall, the success rate approached 90%, with an average MEPS of 87 a mean of 6 years after revision. Overall, patients expressed satisfaction in 74 of 78 (95%) total elbow arthroplasties.

TABLE 54-4 Complications After Coonrad-Morrey Total Elbow Arthroplasty in Rheumatoid Arthritis Requiring Reoperation 10 to 12 Years After Implantation

| Complication | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Aseptic loosening | 3 (4) |

| Triceps avulsions | 3 (4) |

| Deep infection | 2 (2) |

| Ulnar fracture | 1 (1) |

| Ulnar component fracture | 1 (1) |

| Total | 10 (12) |

These are the only long-term results for the Coonrad-Morrey total elbow arthroplasty, and they form the basis for comparison for other total elbow arthroplasty experiences. In our opinion, avulsion of the triceps early in the postoperative period reflects the early learning curve for triceps reattachment using the Mayo approach.7 This complication has not been experienced to any extent in our recent practice (see Chapter 63). The two deep infections (2%) in this most recently reported series represent a marked reduction in the rate of infection compared with previously reported series,34–36 but the rate is higher than that experienced for major joint replacement in the lower extremity at the Mayo Clinic.5,19

We perform the Mayo approach for all primary total elbow arthroplasties in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. We reflect the triceps extensor mechanism and transfer the ulnar nerve with 1 g of gentamicin per 40 g of cement. All elbows are splinted in extension overnight, and active and active-assisted range of motion exercises are begun on the first postoperative day. We do not use physical therapists at any time during the rehabilitation process for the elbow. The long-term Kaplan-Meier survivorship data compare very favorably with total hip arthroplasty data at our institution in rheumatoid patients (see Fig. 54-9).5,24

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS

One comprehensive comparative assessment comparing deficient designs was conducted by Carr et al.29 In this study, the Coonrad/Morrey did outperform the Kudo and Souter Strathclyde by fewer complications and longevity, even though the majority of the Coonrad/Morrey implants had the precoat ulna, known to be vulnerable to osteolysis in a small number of patients.27

CONCLUSION

The reported experience with the semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty is significantly better than that reported for more constrained devices. The experience is also comparable if not better than that reported with the unlinked devices, although the pathologic states that can be addressed are considerably more varied with semiconstrained implants. In fact, the results of the most popular designs now suggest that total elbow arthroplasty approaches the reliability of lower extremity joint arthroplasty.15 Attention to technique remains important, but the success with the full spectrum of pathologic conditions in rheumatoid patients has led to an expansion of the indications for total elbow arthroplasty.32,35,42

1 Aldridge J.M.3rd, Lightdale N.R., Mallon W.J., Coonrad R.W. Total elbow arthroplasty with the Coonrad/Coonrad-Morrey prosthesis. A 10 to 31 year survival analysis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2006;88B:509.

2 An K. Kinematics and constraint of total elbow arthroplasty. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(1 suppl S):168S.

3 Angst F., Goldhahn J., John M., Herren D.B., Simmen B.R. Comparison of rheumatic and post-traumatic elbow joints after total elbow arthroplasty. Comprehensive and specific evaluation of clinical picture, function, and quality of life. Orthopade. 2005;34:794.

3a Bayley J.L.L. Elbow replacement in rheumatoid arthritis. Recon. Surg. Traumat. 1981;18:70.

4 Bell S., Gschwend N., Steiger U. Arthroplasty of elbow: Experience with the Mark III 65B prosthesis. Austr. N. Z. J. Surg. 1986;56:823.

5 Berry D.J., Harmsen W.S., Cabanela M.E., Morrey B.F. Twenty-five year survivorship of 2000 consecutive primary Charnley total hip arthroplasties. Factors affecting survivorship of acetabular and femoral components. J. Bone Joint Surg.. 2002;84A:171.

6 Brumfield R.H., Kushner S.H., Gellman B., Redix L., Stevenson D.V. Total elbow arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty. 1990;5:359.

7 Bryan R.S., Morrey B.F. Extensive posterior exposure of the elbow: A triceps sparing approach. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1982;166:188.

8 Cesar M., Roussanne Y., Bonnel F., Canovas F. GSB III total elbow replacement in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2007;89B:330.

9 Connor P.M., Morrey B.F. Total elbow arthroplasty in patients who have juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1998;80A:678.

10 Davis R.F., Weiland A.J., Hungerford D.S., Moore J.R., Volenec-Dowling S. Nonconstrained total elbow arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1982;171:156.

11 Dennis D.A., Clayton M.L., Ferlic D.C., Stringer E.A., Branlett K.W. Capitello-condylar total elbow arthroplasty for rheumatoid arthritis. J. Arthroplasty. 1990;5(suppl):S83.

12 Ewald F.C., Simmons E.D.Jr., Sullivan J.A., Thomas W.H., Scott R., Poss R., Thornhill T.S., Sledge C.B. Capitellocondylar total elbow replacement in rheumatoid arthritis: Long-term results. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1993;75A:498.

13 Figgie M.P., Su E.P., Kahn B., Lipman J. Locking mechanism failure in semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15:88.

14 Garrett J.C., Ewald F.C., Thomas W.H., Sledge C.B. Loosening associated with GSB hinge total elbow replacement in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1977;127:170.

15 Gill D.R.J., Morrey B.F. The Coonrad-Morrey total elbow arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: 10-15 year follow-up study. J. Bone Joint Surg.. 1998;80A:1327.

16 Gschwend N. Present state of the art in elbow arthroplasty. Acta Orthop. Belg. 2002;68:100.

17 Gschwend N., Loehr J., Ivosevic-Radovanovic D., Sheier H., Munzinger U. Semiconstrained elbow prosthesis with special reference to the GSB III prosthesis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1988;232:104.

18 Gschwend N., Simmen B.R., Matejovsky Z. Late complications in elbow arthroplasty. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5:86.

19 Hanssen A.D., Fitzgerald R.H.Jr., Osmon D.R. The infected total hip arthroplasty. In: Morrey B.F., editor. Reconstructive Surgery of the Joints. 2nd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1996:1229.

20 Hildebrand K.A., Patterson S.D., Regan W.D., MacDermid J.C., King G.J. Functional outcome of semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2000;82A:1379.

21 Inglis A.E., Pellicci P.M. Total elbow replacement. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1980;62A:1252.

22 Jensen C.H., Jacobsen S., Ratchke M., Sonne-Holm S. The GSB III elbow prosthesis in rheumatoid arthritis: a 2-9 year follow-up. Acta Orthop. 2006;77:143.

23 Kasten M.D., Skinner H.B. Total elbow arthro-plasty: An 18-year experience. Clin. Orthop. 1993;290:177.

24 Kavanagh B.F., Dewitz M.A., Ilstrup D.M., Stauffer R.N., Coventry M.B. Charnley total hip arthroplasty with cement: Fifteen-year results. J Bone Joint Surg. 1989;71A:1496.

25 King G.J., Adams R.A., Morrey B.F. Total elbow arthroplasty: Revision with use of a non-custom semiconstrained prosthesis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1997;79A:394.

26 Kraay M.J., Figgie M.P., Inglis A.E., Wolfe S.W., Ranawat C.S. Primary semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty. Survival analysis of 113 consecutive cases. J. Bone Joint Surg.. 1994;76B:636.

26a Leber C., Melone C.P.Jr. Total elbow replacement. Orthop. Rev. 1988;17:85.

27 Lee B.P., Adams R.A., Morrey B.F. Polyethylene wear after total elbow arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2005;87A:1080.

28 Lee K.T., Singh S., Lai C.H. Semi-constrained total elbow arthroplasty for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis of the elbow. Sing. Med. J. 2005;46:718.

29 Little C.P., Graham A.J., Karatzas G., Woods D.A., Carr A.J. Outcomes of total elbow arthroplasty for rheumatoid arthritis: Comparative study of three implants. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2005;87A(11):2439-2448.

30 Lo C.Y., Lee K.B., Wong C.K., Chang Y.P. Semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty in Chinese rheumatoid patients. Hand Surg. 2003;8(2):187-192.

31 Loreto C.A., Rollo G., Comitini V., Rotini R. The metal prosthesis in radial head fracture: Indications and preliminary results. Chir. Organi Mov. 2005;90:253.

32 Madsen F., Gudmundson G.H., Søjberg J.O., Sneppen O. Pritchard Mark II elbow prosthesis in rheumatoid arthritis. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1989;60:249.

33 Morrey B.F. Semiconstrained total elbow replacement. In: Morrey B.F., Thompson R.C.Jr., editors. The Elbow. Master Techniques in Orthopaedic Surgery. New York: Raven Press; 1994:231-255. (series ed.)

34 Morrey B.F., Adams R.A. Semiconstrained arthroplasty for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74A:479.

35 Morrey B.F., Adams R.A. Semiconstrained elbow replacement for distal humeral nonunion. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1995;77B:67.

36 Morrey B.F., Bryan R.S. Infection after total elbow arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1983;65A:330.

37 Plausinis D., Greaves C., Regan W.D., Oxland T.R. Ipsilateral shoulder and elbow replacements: on the risk of periprosthetic fracture. Clin. Biomech. 2005;20:1055.

38 Pritchard R.W. Long-term follow-up study: Semiconstrained elbow prosthesis. Orthopaedics. 1981;4:151.

39 Pritchard R.W. Total elbow arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;21:24.

40 Risung F. The Norway elbow replacement: design, technique and results after nine years. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1997;79B:394.

41 Rosenberg G.M., Turner R.H. Nonconstrained total elbow arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1984;187:154.

42 Schneeberger A.G., Adams R.A., Morrey B.F. Semiconstrained total elbow replacement for the treatment of post-traumatic osteoarthrosis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1997;79A:1211.

43 van der Lugt J.C., Rozing P.M. Systematic review of primary total elbow prostheses used for the rheumatoid elbow. Clin. Rheum. 2004;23:291.