Chapter 29 LIMP

Causes of Abnormal Gait

Congenital Problems and Bone Disorders

Key Historical Features

Time of onset of limp or abnormal gait

Time of onset of limp or abnormal gait

Getting better, getting worse, or staying the same

Getting better, getting worse, or staying the same

Time of day when the pain occurs

Time of day when the pain occurs

Painful versus painless limping

Painful versus painless limping

Unexplained weight loss or lack of appropriate growth

Unexplained weight loss or lack of appropriate growth

Past trauma to the lower extremity or back

Past trauma to the lower extremity or back

Missing school or change in normal activity

Missing school or change in normal activity

Symptoms better with rest or worse with strenuous activity

Symptoms better with rest or worse with strenuous activity

Relative increase or decrease in physical activity

Relative increase or decrease in physical activity

Clumsiness or lack of coordination

Clumsiness or lack of coordination

Family history of connective tissue disease

Family history of connective tissue disease

Review of systems, especially fever, weight loss, rash, and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms

Review of systems, especially fever, weight loss, rash, and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms

Key Physical Findings

Observation of gait and stance

Observation of gait and stance

Symmetry of in-toeing, out-toeing, or toe walking

Symmetry of in-toeing, out-toeing, or toe walking

Complete palpation of leg musculature for focal tenderness

Complete palpation of leg musculature for focal tenderness

Examination of each joint in the legs for swelling, erythema, warmth, or tenderness

Examination of each joint in the legs for swelling, erythema, warmth, or tenderness

Palpation of the spine for local tenderness

Palpation of the spine for local tenderness

Observation of the spine in forward flexion to evaluate range of motion and identify asymmetric turning of the spine

Observation of the spine in forward flexion to evaluate range of motion and identify asymmetric turning of the spine

Evaluation of spinal extension

Evaluation of spinal extension

Full range of motion at the hips, knees, and ankles

Full range of motion at the hips, knees, and ankles

Measurement of thigh and calf circumference to evaluate for atrophy

Measurement of thigh and calf circumference to evaluate for atrophy

FABER test (hip flexion, abduction, and external rotation) to evaluate for pain in the sacroiliac joint

FABER test (hip flexion, abduction, and external rotation) to evaluate for pain in the sacroiliac joint

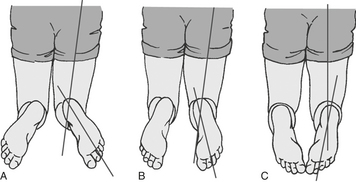

Inspection of forefoot angle and foot shape (Figures 29-1 and 29-2)

Inspection of forefoot angle and foot shape (Figures 29-1 and 29-2)

Examination of the feet for clawing of the toes or cavus foot deformity

Examination of the feet for clawing of the toes or cavus foot deformity

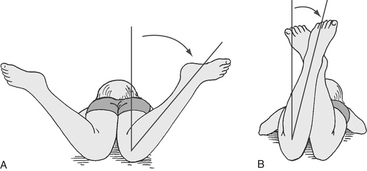

Examination of foot angle with respect to the thigh (Figure 29-3)

Examination of foot angle with respect to the thigh (Figure 29-3)

Focused neurologic examination

Focused neurologic examination

Evaluation of symmetry internal rotation of the hips by placing the child in the prone position with the knees flexed and the ankles falling away from the body (Figure 29-4)

Evaluation of symmetry internal rotation of the hips by placing the child in the prone position with the knees flexed and the ankles falling away from the body (Figure 29-4)

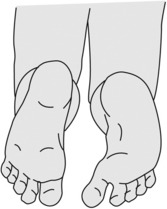

Galeazzi test to evaluate for developmental dysplasia of the hip or a leg-length discrepancy (Figure 29-5)

Galeazzi test to evaluate for developmental dysplasia of the hip or a leg-length discrepancy (Figure 29-5)

Figure 29-1 Observation of long axis of foot for medial deformity of metatarsals in relation to long axis of feet.

(From Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 17th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2004:23–66.)

Figure 29-2 Foot shape. Using the same position for measurement of the thigh-foot angle, in Figure 29-3 the shape of the foot can also be evaluated. In this illustration, the left foot has normal alignment, whereas the right foot demonstrates metatarus adductus.

(From Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 17th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2004:23–66.)

Initial Work-up

| Complete blood count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and/or C-reactive protein (CRP) | If infection or leukemia is being considered |

| Aspiration of the joint with fluid analysis for cell counts, Gram stain, aerobic and anaerobic cultures, protein, and glucose. Include a culture for gonorrhea if the patient is sexually active | If a septic process is suspected |

| Plain films of the areas in question. Films of the entire extremity should be considered for referred pain. Films of the entire extremity should be strongly considered in the nonverbal patient (a fracture is identified in 20% of these patients with a limp) | To evaluate the bones and joints |

Additional Work-up

| Ultrasonography of the hip to identify fluid in the hip joint | Useful when infection of the hip is suspected |

| Alkaline phosphatase, calcium, electrolytes | If a neoplastic process is suspected |

| Serum rheumatoid factor | If inflammatory disease is suspected, though inflammatory diseases in children often are seronegative |

| Creatine kinase | If Duchenne muscular dystrophy is suspected |

| Bone scan | May be considered when the cause of a child’s limp cannot be localized by history or physical examination |

| Computed tomography (CT) scan (best to evaluate bone structure) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI; best to evaluate tissue) | To further evaluate bright areas on bone scan, to further evaluate a particular part of a limb in question, or to evaluate the lumbosacral spine |

1. Behrman R.E., Kliegman R.M., Jenson H.B. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 17th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2004. 23-66

2. Casselbrant M.L., Mandel E.M. Balance disorders in children. Neurologic Clin. 2005;23:807–829.

3. Crawford A.H., Gabriel K.R. Foot and ankle problems. Orthop Clin North Am. 1987;18:649–666.

4. Kogan M., Smith J. Simplified approach to toe-walking. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21:790–791.

5. Leet A.I., Skaggs D.L. Evaluation of the acutely limping child. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61:1011–1018.

6. Thompson G.H. Gait disturbances. In: Kliegman R.M., editor. Practical Strategies in Pediatric Diagnosis and Therapy. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2003:823–843.