CHAPTER 29 Limited Open Osteochondroplasty for the Treatment of Anterior Femoroacetabular Impingement

Indications

Surgical treatment

Hip Arthroscopy

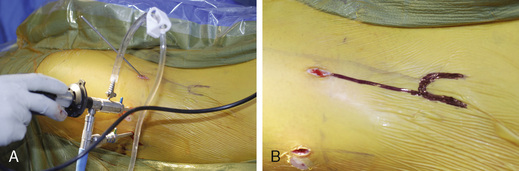

We make use of the anterior, anterolateral, and posterolateral portals for arthroscopic surveillance (Figure 29-1). These portals are established with fluoroscopic assistance by placing 4.0-mm, 4.5-mm, and 5.0-mm hip arthroscopy cannulas. The joint is systematically evaluated with 70-degree and 30-degree angled arthroscopes. The articular cartilage of the femoral head, the acetabulum, and the acetabular labrum are inspected. In patients with an anterior FAI complex, degenerative tears of the anterior and acetabular labrum are common. These lesions are frequently associated with the delamination of the adjacent articular cartilage at the transition zone, and they are addressed with the appropriate arthroscopic technique. After the joint is inspected, the final arthroscopic plan is developed.

Limited Open Osteochondroplasty

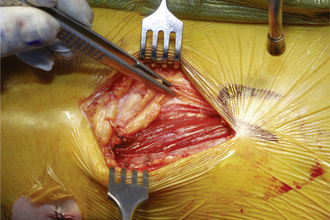

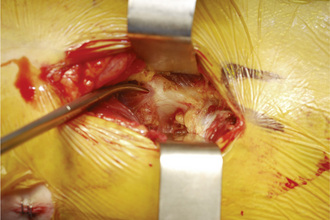

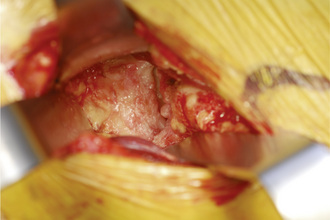

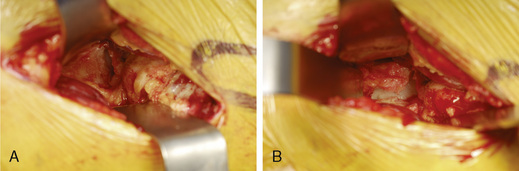

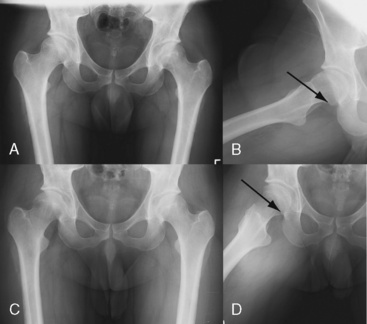

During the second part of the procedure, the patient remains in the same position. After the traction is released, the central post is removed. An anterior longitudinal incision of 8 cm to 10 cm is made starting just distal and lateral (2 cm to 3 cm) to the anterosuperior iliac spine (see Figure 29-1). The dissection is extended laterally in the subcutaneous tissue to dissect directly onto the fascia of the tensor fascia lata muscle. The fascia is incised, the muscle belly is retracted laterally, and the fascia is retracted medially (Figure 29-2). This medial sleeve of tissue contains the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, which should be protected by placing the fascial incision lateral to the tensor sartorius interval. The interval between the tensor and the sartorius is then developed, and the origin of the rectus femoris is identified (Figure 29-3). Next, the direct and reflected heads of the rectus femoris are released. The rectus is reflected distally, and the adipose tissue and the iliocapsularis muscle fibers are dissected off of the anterior hip capsule (Figure 29-4). Alternatively, the direct head of the rectus may remain intact and be retracted medially. An “I”-shaped capsulotomy is then performed to provide adequate exposure of the anterolateral head–neck junction (Figure 29-5). Most commonly, an outgrowth of osteochondral tissue is observed along the anterolateral head–neck junction (Figure 29-6). The offset from the femoral head to the neck in this region is deficient. The normal head–neck offset anteromedially serves as a reference point for the resection of the abnormal osteochondral lesion. In addition, we almost always observe a marked delineation between the normal articular cartilage of the femoral head and the impinging rim (see Figure 29-6). A ½-inch curved osteotome is used to perform an osteoplasty at the head–neck junction. The osteotome is directed distally and posteriorly to perform a beveled resection to prevent the delamination of the retained femoral head articular cartilage (Figure 29-7). After the osteoplasty is performed and the head–neck offset is re-established, the accuracy of the surgical resection is confirmed with intraoperative fluoroscopy. The Dunn view or the frog-leg lateral view is effective for visualizing the anterolateral head–neck junction and for assessing the reconstruction. The hip can also be examined at this time to assess impingement during hip flexion and during combined flexion and internal rotation; this is performed while palpating the anterior hip to test for residual impingement. If the anterior acetabular rim was overgrown as a result of labral calcification or osteophyte formation, this is carefully debrided until adequate clearance is achieved. Hip motion should improve at least 5 degrees to 15 degrees in flexion and 5 degrees to 20 degrees in internal rotation. The goal of the osteoplasty is to remove all prominent anterolateral osteochondral tissue that contributes to an aspheric shape of the femoral head (Figure 29-8). Bleeding from the surface of the osteoplasty is controlled with bone wax. The joint is irrigated, and the longitudinal and superior transverse arms of the arthrotomy are closed with absorbable sutures. The direct and reflected heads of the rectus tendon, if released, are repaired with nonabsorbable suture, and the remainder of the wound is closed in a standard fashion.

Technical Pearls

Labral Debridement or Repair

Limited Open Osteochondroplasty

Results and outcomes

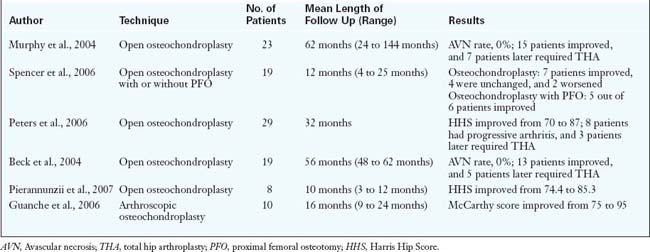

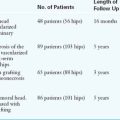

The results of these procedures are summarized in Table 29-1, but highlights include the following:

Annotated references and suggested readings

Beaule P.E., Allen D.J., Clohisy J.C., Schoenecker P., Leunig M. The young adult with hip impingement: deciding on the optimal intervention. J Bone Joint Surg Am.. 2009;91(1):210-221.

Beck M., Leunig M., Parvizi J., Boutier V., Wyss D., Ganz R. Anterior femoroacetabular impingement: part II. Midterm results of surgical treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. (418); 2004:67-73.

Byrd J.W. Hip arthroscopy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg.. 2006;14(7):433-444.

Clohisy J.C., McClure J.T. Treatment of anterior femoroacetabular impingement with combined hip arthroscopy and limited anterior decompression. Iowa Orthop J.. 2005;25:164-171.

Ganz R., Parvizi J., Beck M., Leunig M., Nötzli H., Siebenrock KA. Femoroacetabular impingement: a cause for osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. (417); 2003:112-120.

Guanche C.A., Bare A.A. Arthroscopic treatment of femoroacetabular impingement. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(1):95-106.

Murphy S., Tannast M., Kim Y.J., et al. Debridement of the adult hip for femoroacetabular impingement: indications and preliminary clinical results. Clin Orthop.. 2004;429:178-181.

Peters C.L., Erickson J.A. Treatment of femoro-acetabular impingement with surgical dislocation and debridement in young adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am.. 2006;88:1735-1741.

Philippon M.J., Maxwell R.B., Johnston T.L., Schenker M., Briggs K.K. Clinical presentation of femoroacetabular impingement. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc.. 2007;15(8):1041-1047.

Philippon M.J., Stubbs A.J., Schenker M.L., Maxwell R.B., Ganz R., Leunig M. Arthroscopic management of femoroacetabular impingement: osteoplasty technique and literature review. Am J Sports Med.. 2007;35(9):1571-1580.

Pierannunzii L., d’Imporzano M. Treatment of femoroacetabular impingement: a modified resection osteoplasty technique through an anterior approach. Orthopedics. 2007;30(2):96-102.

Spencer S., Millis M.B., Kim Y.J. Early results of treatment of hip impingement syndrome in slipped capital femoral epiphysis and pistol grip deformity of the femoral head-neck junction using the surgical dislocation technique. J Pediatr Orthop.. 2006;26(3):281-285.

Tannast M., Siebenrock K.A., Anderson S.E. Femoroacetabular impingement: radiographic diagnosis—what the radiologist should know. AJR Am J Roentgenol.. 2007;188(6):1540-1552.

Tanzer M., Noiseux N. Osseous abnormalities and early osteoarthritis: the role of hip impingement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. (429); 2004:170-177.