Chapter 6 Limb problems

6.1 Introduction

Diseases of the arterial, venous, lymphatic, neurological and musculoskeletal systems of the limbs produce specific symptoms requiring special examination techniques for each system. These techniques are discussed in more detail under the clinical problems that arise from diseases of the bones, joints, vessels, nerves and other structures of the upper and lower limbs. It is essential to compare both sides during examination. In all patients it should be routine to test the urine for diabetes, a common aetiological factor in diseases affecting the lower limb.

Arterial circulation

Examination

2 Palpation

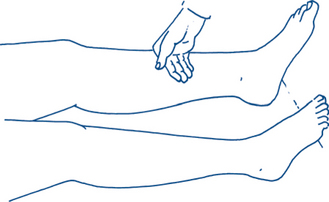

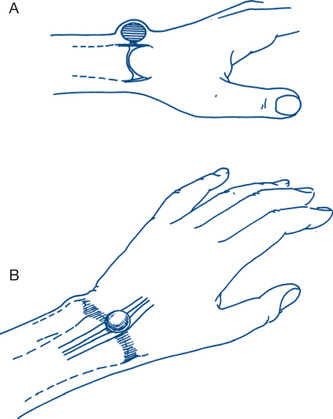

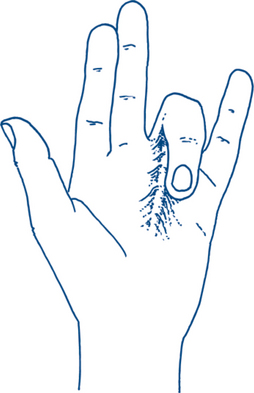

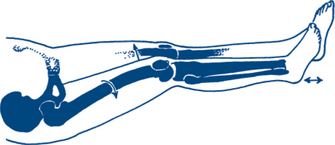

The leg with arterial ischaemia is cool, a sign that is emphasised by comparison with the other side. Skin temperature is best appreciated by palpation using the sensitive thin skin over the dorsum of the middle phalanges (Fig 6.1). Diminished capillary return is present if more than two seconds is taken for colour to return after finger pressure is applied to the big toe.

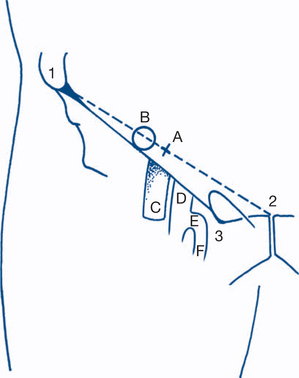

The peripheral pulses in the affected limb are diminished or absent. The dorsalis pedis artery runs from a point midway between the malleoli to the space between the first and second metatarsal bones and is just lateral to the extensor hallucis longus on the forefoot. The dorsalis pedis may be absent in 5–10% of the population and its place may be taken by a branch of the peroneal artery. The pulse will then be felt more laterally. The posterior tibial artery is found in the soft tissue groove below and behind the medial malleolus, halfway between it and the Achilles tendon. The popliteal pulse is the most difficult to find and is best palpated in the lower popliteal fossa with the knee passively flexed. Beware that an easily felt popliteal pulse is often a sign of a pathologically enlarged popliteal artery. The femoral pulse is usually easily palpable in the groin at the midinguinal point (Fig 6.2). The effects of exercise on the appearance of the limb and on distal pulses should be assessed. In moderately severe disease, palpable pulses may disappear on exercise. It is also important to remember the surface landmarks for the various pulses in situations of ‘extremis’ when pulses may be very weak. The abdominal aorta and iliac vessels should also be examined.

Venous circulation

Examination

1 Inspection

The legs are inspected for visible varices involving the long and short saphenous venous systems. A small proportion will also show evidence of chronic venous insufficiency. In patients with chronic venous insufficiency, inspection reveals visible subcutaneous or varicose veins together with bluish-red patches of minute intradermal vessels, known as ankle or malleolar flares or venous stars. The skin in the region of the lower medial third of the leg (gaiter area) shows the signs of venous hypertension: apart from malleolar flares these are: the brown pigmentation of extravasated haemosiderin; dry eczema with a ‘psoriatic’ skin reaction; sclerosing periangiitis with subcutaneous induration; and fibrosis and ulceration. With chronic ulceration and fibrosis, the leg takes the permanent shape of an inverted bottle; contracture may be sufficient to produce an equinus deformity of the ankle and a characteristic waddling gait.

Neurological system

This system is discussed in more detail in Chapter 5. The following is a brief summary relevant to limb examination.

Examination

1 Motor nerve function

Muscle power is tested by active movement against resistance and graded from 0 to 5 therefore (see Tables 5.1 and 5.2):

4 Gait

Bilateral abductor dysfunction or weakness may result in a waddling gait. Waddling gait may also be seen in obese patients, those with bilateral congenital dislocation of the hips and in patients with muscular dystrophy affecting the trunk and pelvic girdle muscles. In those with dystrophy there is often a need to use their hands to climb up their own thighs when getting up from lying down (‘Gower sign’). A short leg results in a limp that can easily be recognised. A stiff knee and hip results in the leg often being swung out (circumducted) as it is brought forward to take a step (using pelvic rotation to advance it rather than hip or knee flexion). In the hemiplegic gait the foot is dragged and the toes are scraped along the ground. With each step the affected limb is circumducted at the hip and swung out and the pelvis on that side tilts forward (see also Ch 5).

Musculoskeletal locomotor system

Examination

2 Palpation

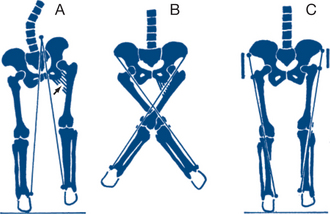

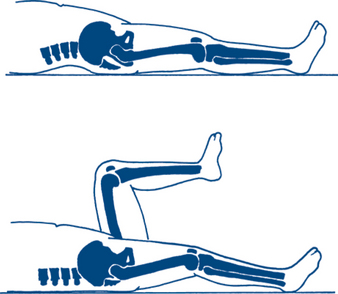

There is a temptation to commence this part of the process by poking the painful area — something best avoided until closer to the end of the examination. Signs of heat, tenderness, swelling or oedema are noted by a hand laid gently onto the affected limb segment. Any localised swelling is noted and its physical characteristics recorded. In the supine patient, one leg may appear to be shorter than the other (apparent shortening — measured from the malleolus to a fixed point on the trunk such as the umbilicus). True shortening of the limb is established by comparing the distance on both sides from the tip of the medial malleolus to a fixed point on the bony pelvis — the anterior superior iliac spine. Accurate measurement of true shortening requires that the joints of both limbs be in an identical position, with the pelvis square to the sagittal plane and both iliac spines at right angles to the line of the spine (Fig 6.3). A fixed abduction or adduction deformity of one limb can cause apparent lengthening or shortening of that side — true shortening is checked after placing the opposite limb in a similar position of abduction or adduction. True shortening is often due to hip disease. The level can be simply and rapidly demonstrated by the disparity in span shown on bilateral palpation of the hip joint — placing the thumb on the anterior superior iliac spine and the middle finger on the greater trochanter and measuring by eye any disparity in distance between these digits on each side.

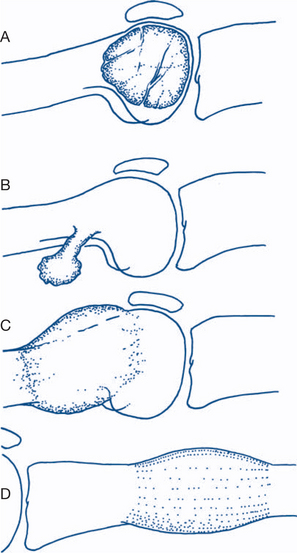

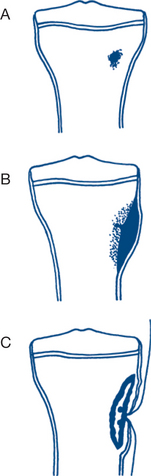

6.2 Bony lumps

The usual causes of bony lumps are injuries, benign or malignant neoplasms and malformation and inflammatory lesions (Fig 6.4). A history of injury suggests reparative bony callus as a cause. It must be remembered that fractures may occur through a pathological focal lesion and sometimes normal bones fracture with no history of injury. Primary bone neoplasms are much less common than are secondary tumours but are more common as a cause of a painfully enlarging mass in the bone. Secondaries in the bone more often present with pain alone or as a spontaneous or pathological fracture. Infections, soft tissue sarcoma and benign developmental skeletal abnormalities can also present as a painful bony swelling. Bony swellings near a joint can be mistaken for an inflammatory monoarticular arthritis. In some instances it may be difficult to tell whether a limb swelling is arising from the bone or from adjacent soft tissues. Normally, when a soft tissue swelling arises primarily from bone, it involves all layers and radiates more or less symmetrically from the bone outwards. The adjacent joints are usually normal.

The most common causes of localised bony swelling in patients aged under 25 years are fracture, callus formation, acute osteomyelitis and osteosarcoma; aged from 25 to 50 years, giant cell tumour, fibrosarcoma and chondrosarcoma; aged over 50 years, metastatic bone disease, localised myeloma and fibrosarcoma (Table 6.1). Nearly all benign tumours occur in the young and stop growing when growth is completed, so diagnosis of these is easy to make in most cases. Large tumours are not necessarily malignant, although recent increase in size does suggest the possibility of malignant change. The main features that suggest malignancy are pain, warmth and tenderness with cortical destruction on X-ray and calcification that extends into the soft tissues. The most common benign tumours are exostoses (bony hard lesions fixed to the bone found near the lower end of the femur and upper end of the tibia), osteomas (flat bony swellings frequently found on the forehead) and chondromas. Chondromas may grow in or out from the surface of the bone. Enchondroma within the bone may present as a fusiform swelling of the bone. Biopsy is essential when malignancy is suggested clinically and histological confirmation of malignancy is essential prior to radical surgery.

| Age group (years) | Lesion |

|---|---|

| <25 | Fracture, callus formation, acute osteomyelitis, osteosarcoma |

| 25–50 | Giant cell tumour, fibrosarcoma, chrondrosarcoma |

| >50 | Metastatic bone disease, myeloma, fibrosarcoma |

History, physical examination and radiology

1 Callus formation

The most common cause of a bony tumour is exuberant callus formation at a fracture site. In most cases there is a history of injury, but sometimes a palpable callus is felt to develop after some weeks of pain from a spontaneous fracture. It is the latter group where diagnosis may be a problem. The most common sites are rib after paroxysmal coughing, second metatarsal bone after a long walk (‘March fracture’) and the upper end of the tibia (‘Recruit’s fracture’). Examination reveals a relatively nontender fusiform enlargement of the bone. The diagnosis is, as a rule, made easily on X-ray.

2 Acute osteomyelitis

X-rays show a central area of rarefaction, surrounding sclerosis of bone and deposition of subperiosteal new bone. Within about two weeks of the onset of acute osteomyelitis, an area of sclerotic dead bone (sequestrum) will appear in the central area of rarefaction (Fig 6.5). However, X-rays may not show any abnormal features in the first few days of the disease process.

3 Osteosarcoma

Most cases of osteosarcoma (osteogenic sarcoma) occur before the age of 25 years. Occasionally osteosarcoma occurs in the aged patient as a complication of Paget’s disease of bone. Osteosarcomas may also arise in bone that has been irradiated for other reasons. A painful bony lump is the predominant symptom. The onset is usually gradual, with a progressive increase in pain, a variable degree of swelling, local heat, venous engorgement and tenderness. Most sarcomas develop in the medullary cavity near the metaphysis of a major long bone; half lie in the region of the knee. A history of previous trauma may be given, that is, either incidental to the underlying process or has precipitated a pathological fracture. Palpation usually reveals a swelling close to the knee without detectable joint disease and with free joint movement.

7 Metastatic carcinoma

Secondaries are a relatively uncommon cause of painful bony swelling. However, they are the most common bone tumour in patients over the age of 40. The major primary sites that commonly metastasise to bone include a lung, breast, prostate, kidney and thyroid. The vast majority of metastases in bone present with bone pain rather than swelling and a minority present with spontaneous fracture. Kidney and thyroid secondaries are the ones most likely to produce swelling as well as pain. The patient often has a past history of the primary tumour and its treatment, such as mastectomy for carcinoma of the breast. Sometimes symptoms of the primary tumour and its metastases may be synchronous. Approximately 10% of patients with cancer present with bony metastases as the first sign of disease. Some metastases, such as from the kidney, may be so vascular that they resemble an aneurysm. The common sites of metastasis are areas of bone marrow formation such as skull, clavicle, rib, vertebrae and upper femur and humerus. Local radiotherapy will often relieve bone pain. Lesions in long bones resulting in extensive cortical destruction and pain may often require an orthopaedic opinion regarding prophylactic surgery in order to prevent fracture.

Diagnostic and treatment plans

A benign tumour remains localised and on X-ray has a well-defined edge. In contrast, a malignant tumour has the potential to metastasise, growth is rapid and its edge is often ill defined. The features that suggest malignancy on X-ray are cortical destruction and calcification extending into the soft tissues (Fig 6.6).

One of the main management problems is to establish the diagnosis of osteosarcoma and to exclude the differential diagnoses of subacute osteomyelitis or a benign neoplasm. It may also be difficult to distinguish neoplasia from the various cystic diseases of bone. Biopsy and histology generally provide the definitive diagnosis but must be correlated with the other clinical and radiological findings. If the diagnosis remains in doubt, conservative treatment may be started, with careful clinical and radiological observation for a period of time before radical surgery is recommended. With a definitive diagnosis of osteosarcoma surgery combined with chemotherapy improves survival. Limb salvage surgery combined with adjuvant chemotherapy, in the right setting, may provide results that are at least comparable to those with amputation and adjuvant chemotherapy. The chemotherapy is most often administered preoperatively, with the pathologist being able to examine the specimen postoperatively and comment on a better outcome should there be a higher degree of necrosis (preferably greater than 95%). Other malignant tumours may also often require limb ablation surgery.

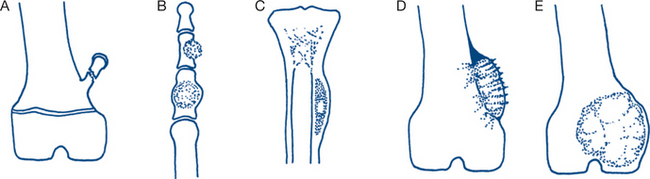

6.3 Musculotendinous lumps

Muscle rupture and degeneration often occur at the junction of the muscle with its tendon or aponeurosis. Sometimes the injury occurs within a tendon widely distant from the parent muscle and presents as a focal lump in the tendon or a spontaneous rupture of the tendon. Symptoms and signs will then be mainly concerned with the tendon; disabilities and deformities induced by active contraction will again be diagnostic.

Benign and malignant neoplasms within and near muscles have their physical characteristics distorted by this proximity — important signs are limited mobility or fixation of the lump when the muscle is tensed and contracted. As well as becoming less mobile, swellings may change in shape and size on muscle contraction. The lump may disappear or become more difficult to feel, suggesting that the lump is within the muscle (Fig 6.7). On the other hand, the lump may occasionally become prominent only when adjacent muscles contract, suggesting extrusion from between muscle bundles or through a defect in the fascial envelope of the muscle. The patient can be asked to contract the muscle isometrically or isotonically to elicit these points or the muscle can be put on the stretch by the examiner, separating origin and insertion by passive joint movements.

Tendinous swellings

Clinical features, diagnostic and treatment plans

Muscle swellings

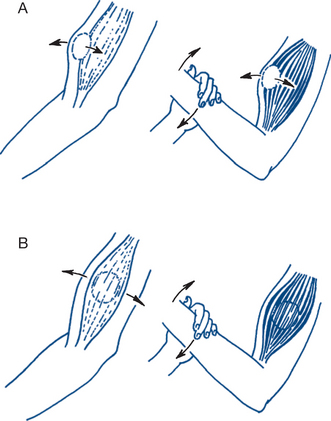

1 Muscle rupture

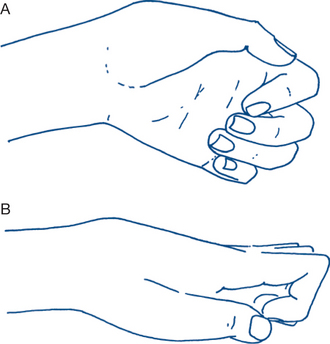

Ruptured long head of biceps brachii tendon. The patient is usually over 50 years; however, the injury may also occur in an athlete performing a large amount of weight training such as bench-press activities. Rupture in the older age group is usually secondary to degenerative weakness and the long head, with its complex intracapsular course over the humeral head, is particularly at risk. The patient may have felt something snap while lifting or flexing the elbow but may not have noted a precipitating event. The clinical picture is unmistakable (Fig 6.8). The belly of the muscle is distorted, looks lower than the other side, does not tighten properly on contraction and is round or semicircular in shape rather than fusiform and ovoid. Shoulder and elbow movements are free and painless — apart from evidence of degenerative joint disease or, occasionally, rheumatoid arthritis. In the younger athlete, sometimes pain may be reproduced by passive stretching of the biceps (Speed’s test) or resisted active contraction (Yergason’s test). While active treatment in either case is rarely required, there is an increasing tendency to repair proximal ruptures in the younger, high-performance athlete. Occasionally the biceps are avulsed from their distal (radial) insertion — this is usually a more acute and painful injury from lifting heavy weights and the muscle belly retracts to a higher position and sometimes requires repair to the bicipital tuberosity in order to preserve full motor power in the younger person.

Supraspinatus (rotator cuff) rupture. This can accompany shoulder injuries such as dislocation or lifting strains. A degenerative rotator cuff in patients over 45 years is more prone to rupture. Active abduction of the shoulder is impaired or not possible, despite an actively contracting deltoid. The shoulder hunches laterally on attempts by the patient to initiate abduction. If the arm is passively elevated through the painful arc, it can be maintained above the head by action of deltoid and the remaining muscles (see Ch 6.4). The treatment of this pathology should include treatment of the tendinopathy and treatment of the associated bony abnormalities. The lateral edge of the acromion may impinge on the rotator cuff during active abduction of the shoulder. Surgical repair of complete rupture is the standard in young patients. In older patients a corticosteroid injection into the subacromial space combined with an exercise program to strengthen the rotator cuff and the periscapular muscles may be all that is required. Surgery in older patients is mainly for the pain-relief associated with alleviating impingement rather than gains in muscle power.

Sternomastoid ‘tumour’. Tearing of sternomastoid muscle fibres can occur in infants, causing a sternomastoid muscle ‘tumour’ with muscle spasm and torticollis (wry neck). The wry neck is seldom visible at birth. Usually within a week or two the parents notice a lump at the lower end of the sternomastoid muscle with the head being held asymmetrically and persistently rotated to one side. As the child spends more time on the one side the face and occiput become more flattened on that side. Treatment is predominantly conservative, with gentle stretching exercises supervised by a paediatric physiotherapist. It is prudent to ask for an orthopaedic opinion in order to exclude congenital cervical vertebral anomalies. The syndrome can also occur in older children and adults. In older children inflammatory conditions of surrounding soft tissue structures, optical disorders and rotatory subluxation of the C1 vertebra on the C2 vertebra are the most common casues. In adults it is more commonly due to a nearby inflammatory lymph node swelling.

2 Intramuscular haematoma

This presents as a painful, tender, firm lump with indistinct edges within a muscle. It often follows an injury during a movement with the muscle under heavy load or after localised contusion. There is associated muscle pain and weakness. Common sites are the thigh, involving quadriceps femoris or hamstring muscles in footballers (‘cork leg’). Treatment is by a brief period of rest; local ice packs and compression, followed by active exercises (Ch 13).

4 Benign or malignant intramuscular neoplasms

‘Desmoid’ tumour (Paget’s tumour). This is a less common form of locally aggressive tumour and usually occurs in the muscles of the anterior abdominal wall. It presents as a firm lump within the rectus muscle of the lower abdomen, often in multiparous women. It requires wide local excision to avoid recurrence (Ch 8.3).

Malignant muscle tumours (fibrosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma). Fibrosarcoma is the most common mesodermal tumour of muscle and presents as a painless intramuscular lump. Distal spread occurs late, the lump may be firm or soft and may be vascular and even demonstrate a soft bruit. It can be difficult to distinguish from a benign haematoma without biopsy. CT scanning and more recently MRI are helpful in the diagnosis and delineation of the extent of suspected tumour masses. The lesions are most common on the limbs and may be close to or attached to bone. Smaller tumours present as completely circumscribed and, as they enlarge, tend to become diffusely infiltrative. Other sarcomas such as rhabdomyosarcoma are more malignant and spread locally and systemically at an early stage. Removal of the tumour is necessary for local control. Treatment requires wide local excision after exploration and biopsy. As local spread tends to be within the muscle bundle, excision should encompass the whole muscle involved, from origin to insertion. Consideration needs to be given to excising the whole compartment in which the muscle is found. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy are often also required. Multimodal therapy involving limb salvage surgery combined with adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy may provide survival rates comparable to amputation and chemotherapy, while preserving a functioning limb.

5 Less common causes

Myositis ossificans. Traumatic myositis ossificans occurs after severe soft tissue or bony injury with lifting and disruption of the periosteum at the site of attachment of muscles and ligaments to bone. Calcification and ossification occur within the soft tissue haematoma. Common sites are around the elbow and knee — within the brachialis, deltoid or quadriceps femoris after fractures and dislocations or tendinous avulsions. Patients present with hard, bony lumps, usually attached to bone at the site of tendinous insertions or in continuity with the callus of a fracture. Initially the swelling may have sharp edges and be painful and tender. Later the swelling’s edges become rounded, tenderness diminishes and the lump may regain a degree of mobility on the underlying bone. Joint stiffness is common, but there are no signs of inflammation. Differentiation from an intrinsic bony swelling can be difficult (Ch 6.2). With a primary swelling of bone, the muscles are usually more freely mobile over the lesion. In myositis, muscle function is impaired and the swelling is in continuity with the muscle.

Tendinous swellings

Stenosing tenosynovitis

De Quervain’s disease (stenosing tenosynovitis of the wrist). This presents as pain and tenderness over the radial styloid process at the site of the common sheath of the tendons of abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis, with pain radiating down to the thumb. A tender nodule may be felt at the site of the constriction while movements of the thumb exacerbate discomfort (e.g. writing or typing). Ulnar deviation of the wrist and thumb in combination is exquisitely painful (Finkelstein’s test), ulnar deviation of the fingers alone much less so.

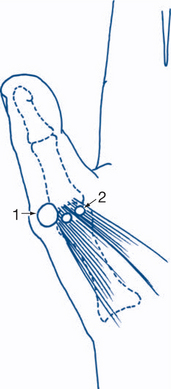

Trigger finger, snapping thumb (stenosing tenosynovitis of the flexor tendons of the hand). This gives a classic and immediately recognisable clinical picture and is a stenosis at the origin of the fibrosynovial flexor sheath just proximal to the metacarpal head in the palm of the hand. The ulnar digits (little and ring) and the thumb are most frequently affected. The power of flexion of the digits is greater than extension so the affected finger can be flexed into the palm but, on attempts to straighten it, remains flexed until straightening occurs on increased effort with a characteristic ‘give’ or jerk. A tender nodule is usually palpable along the course of the tendon just proximal to the metacarpophalangeal joint (see Ch 6.7). The condition has a variable natural history and often resolves spontaneously with time. Recalcitrant and persistent symptoms are easily cured by releasing the tendon pulley just proximal to the fibrous flexor sheath, exposing the nodule in the tendon and checking that free gliding occurs at operation.

6.4 Painful shoulder

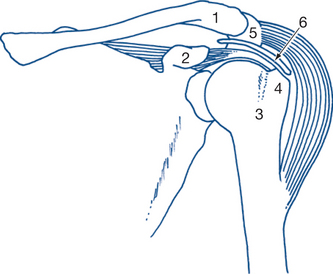

The predominant symptoms of shoulder joint disease are pain, stiffness and loss of function. Pain in the shoulder is usually felt anterolaterally along the edge of the acromion and down the lateral side of the arm. The pain of intrinsic shoulder disease can be difficult to distinguish from that referred from the neck, diaphragm or mediastinum. Ischaemic heart disease may be associated with localised pain in either shoulder. Correlation of anatomy and function is particularly important in the examination of the shoulder. Sites of articulation and movement are designed to allow maximum freedom of action and reach combined with strength. The sites required to move during the various stages of shoulder abduction are the glenohumeral joint, the subacromial space, the acromioclavicular joint, and the sternoclavicular joint (Fig 6.9).

Scapular movement on the thoracic wall allows considerable further range of movement. Stability of the glenohumeral joint is maintained by the tendons of the short rotator muscles — the supraspinatus above, the subscapularis anteriorly and the infraspinatus and teres minor posteriorly. These muscles blend with the capsule of the joint to form the rotator cuff. They act to stabilise the joint during movement and to rotate the arm externally or internally during abduction to allow the great tuberosity to clear the acromion. In the majority of instances, painful shoulder is due to rotator cuff problems. Osteoarthritis of the glenohumeral joint is uncommon. When examining the shoulder, the normal side should always be tested before the abnormal one. Inspection may reveal muscle wasting, swelling or deformity. Local tenderness and stiffness of movement are the most important signs. Active and passive movements may reproduce the pain. If the movement of abduction is painful, it should be noted if this is maximal over a limited arc of abduction. Pain early in the arc of abduction suggests a supraspinatus tear in the mid-range subacromial bursitis and, at the end of abduction, suggests acromioclavicular joint arthritis. Abduction of the arm above the head normally involves a fluid combination of glenohumeral movement and scapular rotation. Frozen shoulder (adhesive capsulitis) can cause complete immobility of the glenohumeral joint, but passive movement to 90° is still possible by rotation of the scapular on the chest wall. Thus, to test for glenohumeral abduction, the angle of the scapula must always be fixed with one hand, while the other moves the patient’s arm. A very sensitive test for frozen shoulder is the lack of shoulder external roration.

History and physical examination

1 Rotator cuff lesions

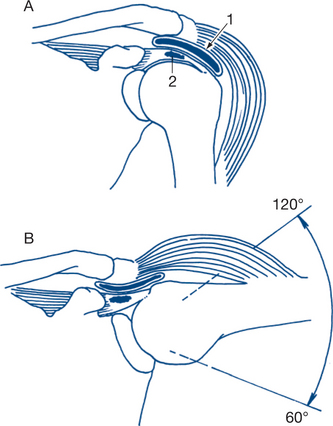

The tendons of the rotator cuff are separated by the subacromial bursa from the bony arch of the coracoid process and the undersurface of the acromion. The pathology of rotator cuff disease consists of three processes: degeneration; traumatic and inflammatory oedema; and bursitis. An insidious onset during middle age, with pain on lifting the arm, particularly in mid-abduction within a painful arc, suggests the presence of chronic supraspinatus tendinitis. The condition is predisposed to overuse and minor trauma, accompanied by degeneration and calcification in the tendon. The pain is often worse at night and is a dull pain felt in the shoulder and down the lateral side of the arm. Local tenderness extends along the edge of the acromion and anteriorly in the angle between the acromion and the coracoid process. Abduction is painful particularly between 60° and 120° of its arc — a ‘painful arc’ (Fig 6.10). The arc may be negotiated with less pain by a trick movement in which the shoulder is dropped while externally rotating the arm to allow the tendon to clear the coracoacromial arch. It is not uncommon to have a bony spur on the undersurface of the acromion. Acute intermittent or cyclical supraspinatus tendinitis also affects young adult females. Pain may increase to an agonising peak over hours, and then subside over the next few days. During the acute attack the arm is held immobile and is too painful to examine. Early calcification of the tendon can occur. In older patients, complete rotator cuff tears in the shoulder may suddenly occur on lifting, without the warning of longstanding shoulder symptoms. Pain is felt immediately and the patient is unable to abduct the arm despite an active deltoid. There may be partial recovery with a persistent painful arc of abduction or gradual development of a frozen shoulder or slow full recovery. Traumatic defects in the rotator cuff are often situated anteriorly, and instability and recurrent anterior dislocation of the shoulder may be associated with the rotator cuff lesion. Chronic cuff tears can predispose the shoulder to osteoarthritis with a humeral head that sits more superiorly than its normal relationship to the glenoid cavity — ‘cuff arthropathy’.

2 ‘Frozen’ shoulder

Frozen shoulder may be primary or secondary in nature. The primary form has vague beginnings and a protracted natural history. It often starts with chronic night pain and a painful arc of abduction characteristic of chronic degenerative tendinitis. Sometimes a history of minor trauma is followed by increasing shoulder pain and tenderness with walking and when the patient lies on the involved shoulder. There are three phases with the first characterised by pain, the second by stiffness — which may last between three and 18 months — and the third by a gradual improvement as the pain subsides and the stiffness improves — ‘thawing’. During the initial period, as the pain lessens, the stiffness of the shoulder increases. Stiffness may progress to involve the hand and elbow; alternatively, any distal lesion of the hand or forearm causing prolonged immobility can lead to secondary shoulder stiffness (‘shoulder–hand syndrome’). Movements of the shoulder are limited in all directions; in severe cases the arm may be held internally rotated, with gross restriction of movement in all directions and muscle wasting. The secondary form may follow significant injuries to the shoulder including fractures and dislocations. Frozen shoulder may also be a part of a complex regional pain syndrome (previously termed reflex sympathetic dystrophy) as in patients after myocardial infarction and stroke.

3 Bicipital tendinitis and rupture

Tendinitis of the long head of the biceps muscle occurs in athletes, particularly those who repeatedly move their arm at the shoulder. Pain is felt on abduction and external rotation of the shoulder with precise localisation of tenderness to the bicipital groove. In older patients chronic bicipital tendonitis is often associated with cuff tears. The proximal biceps tendon may also completely rupture through a degenerated section of tendon. In these cases, function usually returns to near normal after the initial acute pain. On examination, the distorted belly of the long head of the biceps can sometimes be mistaken for a muscle tumour (Ch 6.3).

Treatment plan

Reassurance is important for patients with frozen shoulder; they should be informed that recovery will eventually occur. Once the acute pain has subsided, manipulation under anaesthesia may hasten recovery; however, one must avoid perioperative periarticular fractures. More recently, hydrodilatation of the capsule, which entails radiologically guided overdilatation of the shoulder joint with saline, may hasten recovery. Local anaesthetics and corticosteroids by local injection can assist recovery. Active pendular exercises should commence with resolution of the pain to preserve as much function as possible and assist with rehabilitation.

6.5 Pain in the upper limbs

Referred pain from lesions at another site is common and important. Cardiac ischaemic pain can radiate down the arm or to the neck; occasionally pain at the referred site may seem to be the major or sole presenting problem. Ischaemic pain from peripheral vascular disease can be precipitated by exertion or episodic and precipitated by cold in Raynaud’s syndrome (Ch 6.16). Pain due to cervical spondylosis or, less commonly, to a spinal cord lesion, is another important cause of brachialgia (see Ch 2.18). Local shoulder lesions, particularly of the rotator cuff and subdeltoid bursa, can give shoulder, neck and arm pain (Ch 6.4).

There are four common causes of chronic acral upper limb pain and paraesthesia.

Clinical features and diagnosis

2 Tennis elbow

Tennis elbow, also called baseball elbow, is localised pain due usually to a tendinitis at the origin of the extensor muscles from the lateral epicondyle of the humerus (Fig 6.11). The condition is characterised by precise local tenderness over the dorsal radial head below the epicondyle. Most cases will settle with activity modification and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications. An injection of local corticosteoid or autologous blood at the site of the tenderness is sometimes required. For recalcitrant cases surgical excision of the origin of extensor carpi radialis brevis with decortication of the lateral epicondyle may be required. Tenderness at the origin of the flexor muscles from the medial epicondyle on the other side of the elbow has been called golfers’ elbow. The point of maximal tenderness is usually anterior to the medial epicondyle. The pain can usually be reproduced with flexion of the wrist and pronation of the forearm against resistance. Management is also along conservative lines. Surgery is rarely required. Both conditions can follow repetitive actions such as hammering, sawing and sanding and are frequently related to occupation as well as to sport.

3 De Quervain’s tenosynovitis

De Quervain’s disease is a stenosing tenosynovitis of the extensor pollicis brevis and abductor pollicis longus causing pain and tenderness proximal to the radial styloid process (Fig 6.12). Clinical features are as outlined in Chapter 6.2.

6.6 Subcutaneous hand lumps

Lumps affecting subcutaneous tissues are very common in the hand and warrant special consideration. The disorders that cause them can almost all present at other sites in the body as well. Several such swellings are found more frequently in the hand than elsewhere (implantation dermoid, ganglion) and some (Dupuytren’s disease, giant cell tumour of tendon sheath, Heberden’s nodes) are specific, or almost so, to the hand. Patients present with a focal lump because of concern over appearance or function, pain and fear of cancer. Skin lesions of the hand are common, particularly on the dorsum and many of these are indeed malignant. Subcutaneous lumps are rarely malignant, although local recurrence and invasiveness can occur. Hand infections (Ch 6.8) present as local or diffuse swellings, but severe pain and local or systemic signs of inflammation easily distinguish most infections as a separate group. Gross deformities of the hand and of the fingers are due to contractures of palmar fascias, tendons, joints or nerve palsies and are considered in Chapter 6.7.

Clinical features and diagnostic plan

1 Ganglion

Small localised wrist ganglia. The dorsal ganglion is the most common, located over the dorsal carpus near the proximal tubercle of the capitate, lying to the radial aspect of the midline on the dorsum of the wrist (Fig 6.13). This often arises from the dorsal wrist joint and effective management involves excision of the stalk of the ganglion and repair of the defect in the dorsal wrist capsule.

Small localised ganglia of palm and fingers (‘sesamoid’ ganglia). These ganglia arise from the lateral volar aspects of the fibrous flexor tendon sheath of the metacarpophalangeal joints of the thumb or fingers — usually opposite the metacarpal head. The small firm tense nodule can be confused with the sesamoid bones that lie on the volar aspects of the metacarpophalangeal joints cradling the flexor tendon (Fig 6.14).

2 Synovioma of tendon sheath (benign giant-cell tumour, xanthoma)

These lesions are benign solid neoplasms of tendon sheaths and are virtually confined to the hand. They present as progressive, but slow-growing, firm lumps related to the tendon sheaths of fingers or thumb, usually on the proximal volar surface. They are thus often difficult to distinguish clinically from ganglia. Pain is not usually a marked feature although discomfort occurs with finger movement or gripping. The firm, solid, lobulated mass spreads into tissue planes around the tendon sheath and adjacent joints. They can cause absorption of bone and joint surfaces (usually metacarpal head or proximal phalanx) by compression rather than infiltration and may encircle the bone. They occur in adults of all ages and require surgical excision with an adequate margin because the risk of local recurrence from incomplete excision is high. On exploration, synoviomas are greyish-white lobulated lumps, showing yellow or red areas on the cut surface. On histology, characteristic multinucleated giant cells and foamy macrophages are seen, which are responsible for the yellow colour and the alternative name of xanthoma.

4 Traumatically induced lesions

Traumatic false aneurysms of the radial artery can develop after arterial puncture for blood gas analysis or after a penetrating injury.

Treatment plan: general

Many lesions just require clinical diagnosis and reassurance of the patient (most commonly ganglia, Dupuytren’s nodules and Heberden’s nodes). Persistent discomfort or a suspicion of malignancy requires surgical exploration. Optimal surgical management requires detailed knowledge of hand anatomy and function. Almost all lesions are best explored under an avascular field with a pneumatic tourniquet using either general anaesthesia or brachial plexus block. Adequate removal of ganglia and synoviomas is almost impossible without an avascular field. Because of the compact and complex anatomy of the hand, many lesions are closely associated with important nerves and blood vessels, tendons and joints. An avascular field facilitates preservation of all these structures, but care in avoiding inadvertent arterial damage is very important when operating under a tourniquet. The operation should be concluded and circulation restored within an hour under ordinary circumstances. If prolonged ischaemia is inevitable, it is preferable to release the tourniquet intermittently each hour. Haemostasis is important. Unipolar cautery is never used when operating on the fingers under a tourniquet for fear of thrombosing the digital vessels — bipolar diathermy may be used judiciously. A firm, but not tight, elastic dressing and plaster immobilisation conclude the procedure. After the operation the surgeon must check the hand for circulation. At the end of the procedure, haemostasis (with the tourniquet deflated) is performed in order to avoid the development of a subcutaneous haematoma.

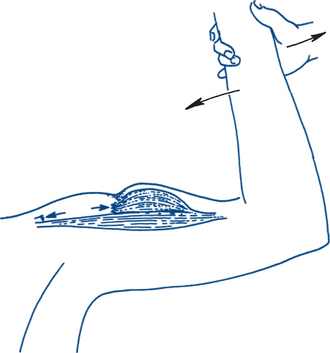

6.7 Hand deformities

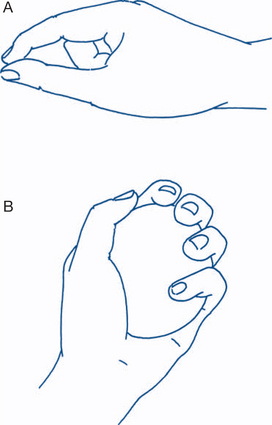

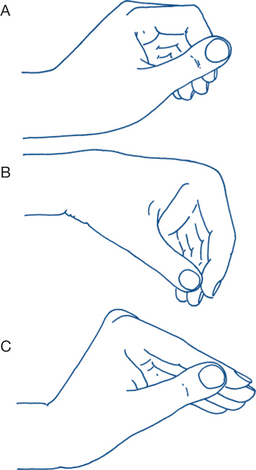

The hand is an intricate and highly sophisticated organ. Even minimum deformity can produce marked disability that can prevent both gainful employment and normal performance of the activities of daily living. Treatment aims to restore, as far as possible, hand functions. These comprise three main areas: sensory perception; fine dextrous movements; and more powerful gripping functions. Manipulative precision, as in the use of fine tools, depends upon sensory perception and dexterity. Precision of grip entails the ability to oppose the thumb with the index and middle fingers. The stronger power grip requires the additional ability to flex strongly the ring and little fingers, combined with powerful movements of wrist, shoulder and elbows (Fig 6.15).

Detailed knowledge of the anatomy and function of the hand is required to prevent and correct deformity. Elective skin incisions must be designed to cause the least interference with hand function and to heal with minimal scarring. Incisions may be placed in flexure skin creases or along lines of cleavage or along the lateral margins of fingers in areas of relative skin immobility (Fig 6.16).

Zig-zag oblique incisions between joint flexure lines can ensure that the incision does not cross the crease line at right angles but does so at the lateral extremities of the creases in areas of less mobile skin. Immobilisation early after surgery promotes healing: ‘every operation on the hand deserves a plaster’. However, the hand tolerates prolonged immobilisation poorly and finger splints should not be maintained for longer than three weeks. The position in which the hand is splinted is also extremely important (Fig 6.17).

In the position of rest, the wrist is slightly flexed and the fingers moderately and progressively flexed into the palm from index to little finger. In the position of function, the wrist is extended and the fingers are a little more flexed. Short-term splinting is usually in the position of function. The lateral ligaments of the finger joints can become shortened during prolonged immobilisation and, to prevent contracture, are preferably kept taut during more prolonged splinting. To do this the metacarpophalangeal joints of the fingers are splinted in flexion with the interphalangeal joints maintained in extension.

History and physical examination

2 Wound contractures

Skin contractures due to secondary scarring of wounds across skin creases, and especially after deep burns, are common causes of deformity. They have a characteristic history and appearance. Surgery may be required in order to improve function; however, there is a tendency for recurrence.

3 Dupuytren’s contracture

As the disease progresses, continuing fibrosis and infiltration involve the subcutaneous tissues and palmar aponeurosis. Diverging bands run from the palm in the region of the flexor retinaculum to the volar aspects of the digits and extend across the metacarpophalangeal joint and proximal interphalangeal joint to the middle phalanx. The terminal interphalangeal joint is usually not involved. The effect of the disease on the end joint of the finger depends upon the degree to which the finger is rolled into the palm by contracture at the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints. The deformity can cause flexion of the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints to a right angle; the distal and intermediate phalanges remain in line and forced against the palm (Fig 6.18). Less commonly the terminal interphalangeal joint is flexed and the affected finger is rolled tightly into the palm with flexion of all joints. All degrees of contracture of the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints occur; the firm subcutaneous fascial bands causing the deformities are easily palpable and often attached to overlying skin. The deformity is unaffected by movements of the wrist joint and there is no sensory disturbance. The contracted fingers impair the grip and make it difficult to let objects go, and also get caught up in pockets.

4 Ischaemic muscle contracture (Volkmann’s)

Volkmann’s ischaemic contracture follows ischaemic fibrosis involving the long flexor muscles of the forearm and gives a disabling and characteristic claw-like deformity of the fingers and wrist. The usual causes of muscle ischaemia are injury to the brachial artery from supracondylar fractures of the humerus or to its branches from fractures of both bones of the forearm or from an excessively tight arm plaster or occasionally after arterial embolism. Prevention of the complication requires adequate treatment of these conditions and effective management of incipient ischaemia from any cause. The major sign of incipient ischaemia of the long flexor muscles of the forearm is extreme pain on attempted finger extension. This should alert the clinician to the danger of ischaemic contracture; it demands immediate diagnosis and relief. The muscle ischaemia involves muscles within the flexor compartment of the forearm, often with secondary involvement of nerves due to ischaemic neuritis. The skin and subcutaneous tissues are not involved and the fingers are paraesthetic but not ischaemic. Muscle ischaemia leads to permanent damage and ultimately fibrosis if ischaemia is not relieved within six to 12 hours. The infarcted muscles undergo progressive fibrotic contracture that particularly affects the long finger flexors and, to a variable degree, the wrist flexors.

In the most severe case the deformity is unmistakable and involves all digits and the whole hand. The wrist is usually held moderately flexed. The metacarpophalangeal joints are in neutral position or extended due to tension of the long extensors and the proximal and interphalangeal joints are grossly flexed (Fig 6.19). Varying degrees of ischaemic neuritis may accompany the contracture. Most often, regeneration of affected nerves occurs so that muscle function of the small muscles of the hand is maintained and sensation of the fingers is present. The deformity and its effects are thus very different from that produced by a claw hand due to a neurologic deficit. It is also soon obvious on examination that the deformity is associated with contracture of the long flexor muscles of the fingers: extension of the wrist worsens the finger deformity and flexion of the wrist diminishes it. The source of proximal ischaemia will be apparent on questioning or examination. The most common findings are an old fracture of the elbow or forearm or a proximal source of vascular embolus.

Fibrous contracture of the small muscles of the hand can also occur, secondary to ischaemia or to rheumatoid arthritis, or to the hypertonicity found in cerebral palsy. The deformity resulting from fibrous shortening of the interossei and lumbricals is very typical and results in metacarpophalangeal flexion of the joints of the fingers and thumb, interphalangeal joint extension and adduction of the thumb. This position is called the ‘intrinsic plus’ hand (Fig 6.20). Minor degrees of contracture of the short muscles are diagnosed by passive hyperextension of the metacarpophalangeal joints; the interphalangeal joints will not be capable of passive flexion in this position, as it stretches the intrinsic muscles of the fingers and thus the dorsal capsules of the distal joints.

5 Tendon disorders

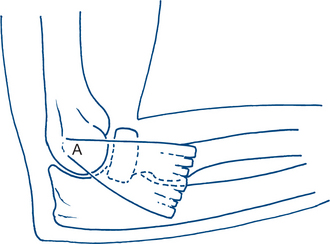

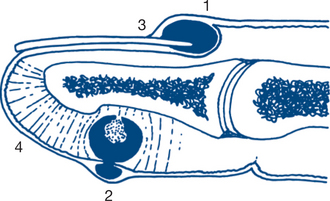

Trigger finger (stenosing flexor tenosynovitis) is a very characteristic condition in which the finger becomes locked in full flexion. Forced active or passive extension is associated with a sudden click and release (Fig 6.21).

Figure 6.21 Trigger finger from stenosing tenosynovitis of the flexor tendon

The finger becomes locked in flexion. Forced extension leads to a sudden click and release.

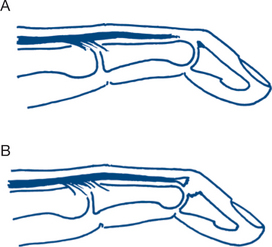

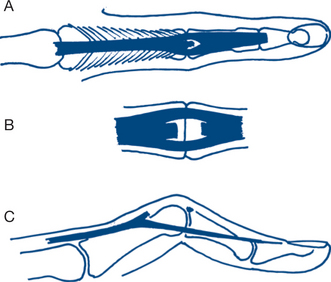

Mallet finger (Fig 6.22) is a flexion deformity of the distal interphalangeal joint caused most commonly by a hyperflexion injury of the finger tip while catching a ball, resulting in rupture of the extensor tendon slip to the base of the distal phalanx. Sometimes the injury is associated with avulsion of a small flake of bone from the dorsal aspect of the base of the distal phalanx. Occasionally, division of the tendon occurs from a penetrating wound. For closed injuries, early treatment by splinting in the hyperextended position can result in healing without final disability or deformity, particularly when a bony fracture is present. However, healing of the tendon is often accompanied by lengthening and deformity, with failure of complete extension on straightening the finger. Passive extension confirms that the deformity is not due to joint stiffness but to tendon weakness (drop finger). The condition may also follow invasion of the extensor tendon and its insertion by rheumatoid inflammatory tissue, in which case other deformities of rheumatoid arthritis are usually obvious. Treatment is usually immobilisation of the distal joint in a hyperextended position in a ‘mallet splint’. Should the piece of bone be large or include a significant segment of articular surface, then surgical repair may be warranted.

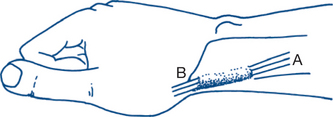

Boutonnière deformity. This is a flexion deformity of the proximal interphalangeal joint due to traumatic division, rupture or stretching of the central slip of the extensor tendon expansion where it inserts into the base of the middle phalanx. The lateral slips separate and dislocate around the sides of the flexed joint and the head of the proximal phalanx protrudes through the gap, as though through a button-hole. Eventually there is hyperextension of the distal interphalangeal joint and fixed flexion of the proximal interphalangeal joint giving a typical deformity (Fig 6.23).

Figure 6.23 Boutonnière deformity

A: normal tendon B: ruptured central slip; C: established deformity

Swan neck deformity is the reverse of the boutonnière deformity. The proximal interphalangeal joint is hyperextended and the distal interphalangeal joint is flexed. The swan neck deformity can be seen in normal hands and is secondary to an imbalance between extensor and flexor tendon action. It is a common deformity in rheumatoid arthritis (Fig 6.24) and is often associated in this disease with other deformities and fibrotic contacture of the interossei and lumbrical muscles. Testing for intrinsic muscle contracture and isolated sublimis action (Ch 5.2), and observing if stabilising the metacarpophalangeal joint corrects the deformity, will usually indicate the cause.

6 Deformities due to arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis. This usually has its most disabling effects on the hands. The disease commonly begins with pain, stiffness and swelling of the fingers. The joints mainly involved are the metacarpophalangeal joints and proximal interphalangeal joints (different to the distal pattern of osteoarthritis). Synovial thickening and associated muscle wasting give the fingers and hands a spindle-shaped deformity. Rheumatoid granulomatous nodules develop in the subcutaneous tissue, usually over bony prominences and within tendon sheaths. Thickening of the dorsal ligaments of the proximal interphalangeal joints causes Bouchard’s nodules. Progressive disease causes the typical deformity of the ‘intrinsic plus’ hand: with thickened deformed wrists and metacarpophalangeal joints, ulnar deviation of the hand and fingers and a Z-deformity of the thumb. Progressive flexion deformity at the metacarpophalangeal joints can progress to subluxation. Hyperextension of the interphalangeal joints, tendon erosion and rupture, swan neck deformity, boutonniere and mallet finger deformities are all common (Fig 6.25).

7 Deformities due to neurological lesions

Peripheral nerve lesions. These give classic hand deformities (Ch 5.3).

Ulnar nerve palsy gives the classic deformity of ulnar claw hand. The characteristic posture enables this to be easily distinguished from the other claw deformities. Only the little and ring fingers are clawed, unless the ulnar nerve supplies all the lumbrical muscles. Sensation is lost over the ulnar side of the hand and over the little finger and the ulnar side of the ring finger. The claw deformity of an ulnar claw hand involves hyperextension at the metacarpophalangeal joints and flexion of the other finger joints (Fig 6.26).

As the metacarpophalageal joints hyperextend due to the lack of hand intrinsic function, full extension of the proximal interphalangeal joints is not possible. Wasting of the small muscles of the hand is present, apart from the short abductor and flexor of the thumb. Functional impairment is significant. With grasping there must be a coordinated action of the long and short flexors in the forearm and hand such that flexion proceeds from the metacarpophalangeal joints to the interphalabgeal joints. With a loss of the interossei and lumbricals there is an inability to selectively initiate flexion at the metacarpophalangeal joint. As such, the remaining long flexor tendons — flexor digitorum superficialis and profundus — curl the fingers into the palm with the metacarpophalangeal joints being activated towards the end of this motion. The arc of finger motion is therefore significantly shortened and large objects are unable to be grasped. Stability of pinch is also affected, as demonstrated using the Froment test — the interphalangeal joint of the thumb flexes to increase the mechanical advantage of the extensor pollicis longus and compensate for the weakened or missing action of the adductor pollicis.

Motor neurone disease and other neurological conditions (syringomyelia, leprosy) can also give claw hand deformities (Box 6.1).

Diagnostic plan

Checking for anaemia and auto-antibodies will be required in assessment for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Conduction studies may be required to assess progress of recovery in nerve lesions.

6.8 Hand infections

Clinical assessment and diagnostic plan

The first evidence of a wound infection is usually the development of pain that is distinguishable from the subsiding pain of the original injury. Systemic effects are initially mild. If the organism is virulent and the infection is confined to the deep fascial spaces under tension, constitutional disturbance is more severe. Throbbing pain disturbing sleep is suggestive of pus and requires mechanical relief by drainage — not just analgesia, antibiotic treatment and splintage. In many cases of hand sepsis there is no obvious wound and the patient presents because of the infection itself. Infections are commonly seen in horny and calloused hands, with potential breaches in the skin surface.

Classification of treatment plan

Three main pathogenic factors provide a classification that guides treatment, as outlined below.

2 Subcutaneous infections

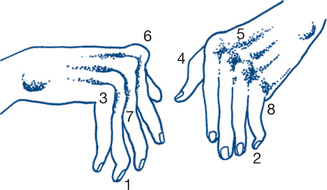

Subcutaneous infections are particularly common with the fingers (Fig 6.27).

Pulp-space infection. Subcutaneous infections of pulp (Whitlow) and web spaces, nail bed, palmar compartments and thenar and hypothenar eminences, are initially treated similarly — with antibiotics and splinting and careful review to identify any developing abscess that requires drainage. If the abscess has not involved the skin, a short incision is made at the point of maximum tenderness — if possible, parallel to the nearest skin crease. If the abscess is carefully cleaned by curettage and any slough is excised, healing will be rapid. Exposure is usually best by a direct approach, combined with careful removal of infected material and antibiotic treatment.

The distal finger pulp is divided into a number of tiny compartments by strong fibrous septa that traverse from the skin to the periosteum. Because of these septa, a pulp space abscess — felon — presents with severe and immediate pain, due to the increase in pressure within the pulp, with early evidence of subcutaneous necrosis. Incision should be combined with excision of slough and treatment with antibiotics (Fig 6.28). Be aware that the felon may extend into the periosteum and around the nail bed.

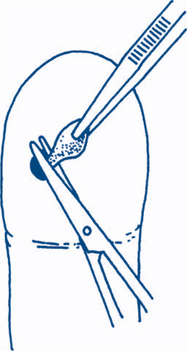

Paronychia. The management of acute paronychia with pus formation depends upon the extent and direction of spread. In early cases, only elevation of the nail fold is required to facilitate drainage. With subungual extension of pus, a small vertical incision alongside the nail or removal of the nail in part or whole may be necessary (Fig 6.29). Staphylococcus aureus is the most common bacterial source in acute infections; however, recent studies have identified a 25% incidence of anaerobic infections. In chronic paronychia, candida albicans is the causative agent in 70–90% of cases.

Hair follicle infections usually appear on the dorsal aspect of the hand. Folliculitis has pus formation within a hair follicle with infection limited to the dermis. A furuncle is an infection of a number of hair follicles within a confined area and a carbuncle is an abscess involving a number of adjacent hair follicles where the infection has penetrated the dermis and formed a subcutaneous abscess. A dorsal abscess is treated by excising the slough, preserving as much viable skin as possible and treating with antibiotics. The treatment of a carbuncle must also include the excision of the abscess and its fibrous septa. Firm bandaging after cleaning out the cavity will result in rapid obliteration of the space. The causative agent is usually a staphylococcal species; however, with lesions below the waist coliforms and anaerobes should also be considered. Diabetes must be excluded in all hand infections. Attention to hygiene is important if recurrence is to be prevented.

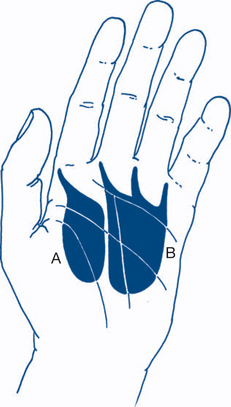

3 Deep infections

Palmar space infection. Most abscesses in the palm or over the thenar eminence lie between the skin and the fascia overlying the muscles and tendons. Most of these infections point early and are best treated by early drainage with excision of slough. However, there are deeper spaces in the palm that may become infected — the thenar, midpalmar and hypothenar spaces. These infections lie between the fascia covering the metacarpals and their associated muscles and the fascia dorsal to the flexor tendons (Fig 6.30). On examination, these deep infections tend to flatten or obliterate the palmar cavity and also produce swelling of the dorsum of the hand. Extension of the fingers may cause severe pain suggestive of tendon sheath infection. Incision into the subcutaneous space is usually made parallel to the nearest skin crease and then into the subfascial space by bluntly separating the fibres of the aponeurosis. Debridement is then performed under direct vision.

Careful rehabilitation is crucial to the full recovery of hand function after infection. The hand is splinted initially in the position of function. Once the infection has been controlled and healing is in progress, graduated finger movement and exercises are begun. In this way, tendon and joint adhesion formation can be minimised and late stiffness of the hand prevented. Contractures may not develop for weeks or months after injury and infection and are especially common in cases where massive scarring is associated with delayed treatment and healing. Infections in wounds crossing the flexor joint creases are especially likely to be complicated by skin contracture. Prevention may require early skin grafting, especially when significant skin loss exists.

6.9 Nail disorders

The nails are commonly the site of pathology. Lesions requiring surgical treatment can usually be distinguished from the nail changes associated with systemic disease (Table 6.2).

| Disease | Nail changes |

|---|---|

| Connective tissue disorders | Periungual erythema and telangiectasis |

| Psoriasis | Pitting, thickening and deformity of nail plate |

| Cyanotic heart disease and chronic lung disease | Clubbing of the fingers (Hippocratic nails) |

| Iron deficiency anaemia | Koilonychia |

| Infective endocarditis | Subungual splinter haemorrhages |

| Cirrhosis | Leuconychia |

| Hypoalbuminaemia | Parallel white bands in the nail bed |

| Renal disease | Half and half nail — white proximal and red distal discolouration of the nail |

| Thyrotoxicosis | Clubbing, onycholysis |

| Local trauma or severe systemic disease | Beau’s lines — transverse grooves |

| Raynaud’s phenomenon | Brittle, thin nails, paronychia |

History and physical examination

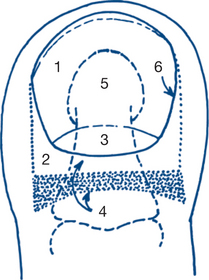

The normal anatomy is shown in Figure 6.31.

1 Subungual haematoma and melanoma

Melanoma must be considered in all patients presenting with a dark spot beneath the nail. A history of trauma does not automatically exclude melanoma. A haematoma is usually reddish-brown with sharp edges. A melanoma forms a dark brown or bluish-black discolouration of the nail bed with indistinct edges. The lesion of melanoma has mass to it and may elevate the nail. There may also be streaks of pigment in the nail plate. Eventually ulceration and bleeding of the nail bed occurs with erosion of overlying nail. Some tumours are amelanotic, forming red friable subungual plaques or papules. In contrast to melanoma, haematomas move distally with nail growth and are often accompanied by a depressed line and ridge (Beau’s line) in the overlying nail. When there is any doubt, the lesion should be treated as a melanoma, by biopsy excision after removal of the overlying nail.

5 Less common conditions

These include onychogryposis, subungual exotosis and glomus tumour.

A glomus tumour is an angioneuromyoma (a benign hamartoma). Presentation is with an exquisitely tender, small purple–red spot beneath the nail. The symptoms are characteristically markedly severe in relation to the physical findings.

Diagnostic and treatment plans

1 Subungual haematoma and melanoma

Excisional biopsy and histological confirmation is essential before amputation of the finger or toe.

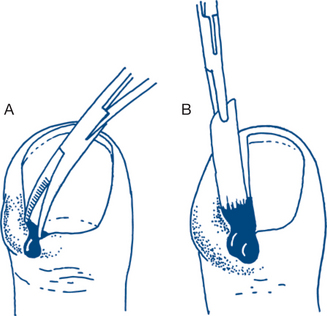

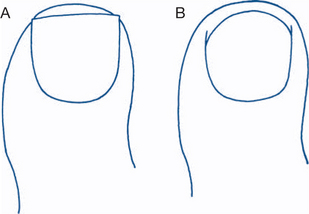

2 Ingrown toenail

All patients with an ingrown toenail should be instructed on correct foot and nail care. The patient is advised to wear correctly fitting shoes and to cut the end of the nail squarely, not at the sides, so that the nail can grow out from the nail fold (Fig 6.32). In the meantime the patient must attend to foot hygiene, including foot baths, avoiding the use of nylon socks and frequent changes of clean cotton or wool socks, and placing cotton wool beneath the nail edge to assist separation of the edge from the nail fold. Thinning the central portion of the nail with a nail file or razor blade makes the edge more pliant and easier to lift away from the nail fold.

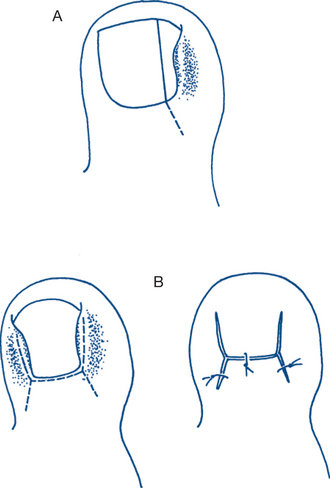

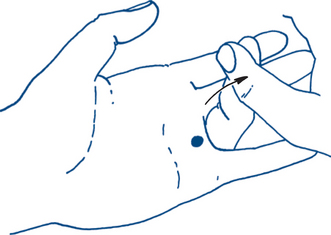

Persistent or recurrent ingrown toenail requires surgical treatment. Avulsion of the nail may be indicated for severe purulent infection, especially when both sides of the nail are involved, and gives very effective drainage. Recurrence occurs on regrowth of the nail in about 30% of patients. Elective surgical treatment involves removal of the offending section of the nail and nail bed (wedge resection) so that regrowth and recurrence will not occur. The operation can be performed under a digital nerve block (Fig 6.33) or under general anaesthesia. Before the procedure is performed, the circulation to the foot must be checked — circulatory problems must be identified in older patients and problems prevented by alternative plans of management.

Figure 6.33 Digital nerve block

Adrenaline must not be added to local anaesthetic for a digital block.

In a simple wedge resection the affected side of the nail is excised and the underlying nail bed surgically removed and curetted, taking particular care to remove the entire lateral extension of the nail bed (the key to success). Zadik’s operation (originally described by Quenu in 1887) is a more radical procedure done for severe and recurrent disease. Two lateral incisions in the eponychium are extended proximally from the edges of the nail fold to allow the raising of a wide flap of skin and also distally along the nail fold so that granulation tissue can be excised. The entire proximal nail bed is excised so that regrowth of the nail does not occur. The exposed nail bed keratinises and becomes less sensitive, forming a ‘pseudo-nail’ with time (Fig 6.34). Incomplete excision may lead to dysmorphic regeneration of the nail and further symptoms.

6.10 Painful hip

Clinical assessment

The gait is first assessed. A short limb may be observed — shortening may be apparent or real (Fig 6.3). A painful, unstable hip is often associated with a Trendelenburg gait. The sound side sags as the good leg is swung through; the trunk is often tilted to come above the affected weight-bearing leg, so as to minimise the abductor moment required to maintain pelvic alignment. This may be tested with the Trendelenburg test where the patient stands on the affected limb while the good leg is lifted from the ground. Should the pelvis sag or the torso be laterally flexed over the affected limb the test is deemed to be positive — indicative of abductor dysfunction or weakness.

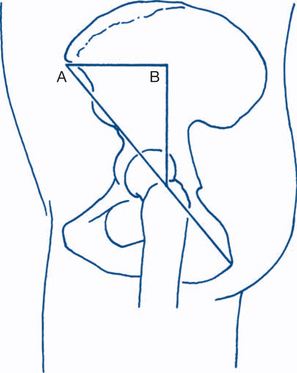

The patient is then examined supine. The hip is buried deeply and is not accessible to direct palpation. An important preliminary step is to set the pelvis square. This is done by placing the line between the anterior superior iliac spines at right angles to the line of the trunk and limbs. True shortening is present when the distance from the top of the femoral head to the medial malleolus is shorter on one side than the other. Because the femoral head is inaccessible, measurements are taken from the nearest bony point — the anterior superior iliac spine. True shortening may be due to shortening of the tibia, femoral shaft or femoral neck or (occasionally) ilium or to dislocations at the hip. Shortening due to femoral neck or femoral head disease can be roughly assessed by placing the thumbs on each anterior superior spine and feeling with the middle fingers for the top of each greater trochanter. More accurate methods of estimating shortening are made by drawing Nelaton’s line or constructing Bryant’s triangle (Fig 6.35).

Passive abduction and adduction of the hip are tested by moving the legs while one hand fixes the ilium, limiting movement to that occuring at the hip alone. To test flexion–extension the sound hip is first flexed to obliterate any lumbar lordosis (Thomas’ test). If by this manoeuvre the other thigh rises from the couch, then a fixed flexion deformity of the hip on that side is revealed (Fig 6.36). In the presence of a flexion deformity of the knee, the patient is moved down the bed such that the knees hang down and the test is repeated. To test rotation, both legs are rotated internally and externally at the ankle and thigh. Observation of patella movement allows rotation at the hip joint to be identified and compared between both sides. The patient is turned prone to test passive extension of the thigh. In the child the rotational profile of the hips (internal versus external rotation) is also measured in the prone position with the hip in neutral abduction.

Examination is completed by assessing the patient for extrinsic causes of hip pain. This may include examination of the spine and sacroiliac joints, a neurological assessment of the lower limbs, pelvic and rectal bimanual examination and examination of the peripheral vascular system.

1 Osteoarthritis

In the majority of patients over 60 years of age with osteoarthritis, no specific risk factors are apparent. In young adults, osteoarthritis is more often a sequelae of traumatic dislocation, slipped upper femoral epiphysis, Perthes’ disease, infection, rheumatoid arthritis or osteonecrosis. Pain is felt in the front of the hip or groin and may radiate down the inside of the thigh to the knee. It occurs with weight-bearing activities. At first the pain is more severe early in the day or when movement follows a period of rest. Later the pain is constant. It may even disturb sleep — particularly in those who turn regularly during sleep. Initally stiffness may manifest itself on rising by difficulty putting on socks and doing up shoe laces. On examination of the patient with moderate to severe disease, the affected leg lies in external rotation and adduction so that it appears to be shorter than the other leg (Fig 6.37). Some degree of flexion deformity can often be demonstrated by Thomas’ test. The greater trochanter can be felt higher and a little posterior on the affected side. Internal rotation, adduction and extension are the first movements to be decreased on examination.