Chapter 126 Leukocytosis

Leukocytosis is an elevation in the total leukocyte, or white blood cell (WBC), count that is 2 standard deviations above the mean count for a particular age (Chapter 708). The various causes of leukocytosis are categorized by the class of leukocyte that is elevated and whether the process is acute, chronic, or lifelong. To evaluate the patient with leukocytosis, it is critical to determine which class of WBCs is elevated, and also the duration and extent of the leukocytosis. Each blood count should be evaluated with regard to the absolute number of cells/µL and the normal range for the patient’s age.

Neutrophilia

Acute Acquired Neutrophilia

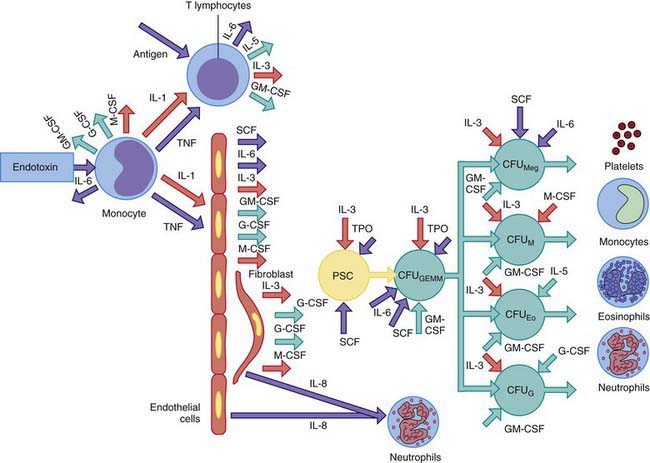

Epinephrine causes release into the circulation of a sequestered pool of neutrophils that normally marginate along the vascular endothelium. Corticosteroids accelerate the release of neutrophils and bands from a large storage pool within the bone marrow and impair the migration of neutrophils from the circulation into tissues. Acute neutrophilia in response to inflammation and infections occurs because of release of neutrophils from the marrow storage pool. The post-mitotic marrow neutrophil pools are approximately 10 times the sizes of the blood neutrophil pool, and about half of these cells are bands and segmented neutrophils. In neutrophil production disorders, such as those associated with malignancies and cancer chemotherapy, the size of this pool may be reduced and the capacity to develop neutrophilia remains impaired. Exposure of blood to foreign substances such as hemodialysis membrane activates the complement system and causes transient neutropenia followed by neutrophilia because of release of bone marrow neutrophils. The colony-stimulating factors G-CSF and GM-CSF cause acute and chronic neutrophilia by mobilizing cells from the marrow reserves and by stimulating neutrophil production (Fig. 126-1).

Chronic Acquired Neutrophilia

Chronic neutrophilia is usually associated with continued stimulation of neutrophil production resulting from persistent inflammatory reactions or chronic infections (e.g., tuberculosis), vasculitis, postsplenectomy states, Hodgkin disease, chronic myelogenous leukemia, chronic blood loss, sickle cell disease, some chronic hemolytic anemias, and prolonged administration of corticosteroids. Chronic neutrophilia can arise after expansion of cell production secondary to stimulation of cell divisions within the mitotic precursor pool, which consists of promyelocytes and myelocytes (see Fig. 126-1). Subsequently, the size of the post-mitotic pool increases. These changes lead to an increase in the marrow reserve pool, which can be readily mobilized for release of neutrophils into the circulation. The neutrophil production rate can increase greatly in response to exogenously administered hemopoietic growth factors, such as rhG-CSF, with a maximum response taking at least 1 wk to develop.

Lifelong Neutrophilia

Congenital asplenia is associated with lifelong neutrophilia. Uncommon genetic disorders that present with neutrophilia include leukocyte adhesion deficiency, familial myeloproliferative disease, Down syndrome, and Rac-2 mutation (Chapter 124). In an autosomal dominant form of hereditary neutrophilia, patients maintain an absolute neutrophil count between 1,400 and 150,000/µL, which is associated with hepatosplenomegaly, an increased alkaline phosphatase level, and Gaucher-type histiocytes in the bone marrow.

Monocytosis

The average absolute blood monocyte count varies with age, which must be considered in the assessment of monocytosis. Given the role of monocytes in antigen presentation and cytokine secretion and as effectors of ingestion of invading organisms, it is not surprising that many clinical disorders give rise to monocytosis (Table 126-1). Most commonly, monocytosis occurs in patients recovering from myelosuppressive chemotherapy and is a harbinger of the return of the neutrophil count to normal. Monocytosis is occasionally a sign of an acute bacterial, viral, protozoal, or rickettsial infection, and may also occur in some forms of chronic neutropenia and postsplenectomy states. Chronic inflammatory conditions can stimulate sustained monocytosis, including preleukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia, lymphomas, and occasionally Hodgkin disease.

Table 126-1 CAUSES OF MONOCYTOSIS

INFECTIONS

Bacterial Infections

Tuberculosis

Brucellosis

Typhoid fever

Syphilis

Infective endocarditis

Nonbacterial Infections

Fungal infections

Rocky Mountain spotted fever

Typhus

Kala-azar

Malaria

HEMATOLOGIC DISORDERS

Postsplenectomy states

Congenital and acquired neutropenias

Hemolytic anemias

MALIGNANT DISORDERS

Preleukemia

Acute myelogenous leukemia

Chronic myelogenous leukemia

Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia

Hodgkin disease

Non-Hodgkin lymphomas

CHRONIC INFLAMMATORY DISEASES

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Rheumatoid arthritis

Polyarteritis nodosa

Inflammatory bowel disease

Sarcoidosis

MISCELLANEOUS

Cirrhosis

Recovery from marrow suppression induced by chemotherapy

Drug reactions

Boxer LA. Leukocytosis. In: Sills RH, editor. Practical algorithms in pediatric hematology and oncology. New York: Karger; 2003:38-39.

Dinauer MC, Newburger PE. The phagocyte system and disorders of granulopoiesis and granulocyte function. In: Orkin SH, Ginsburg D, Nathan DG, et al, editors. Nathan and Oski’s hematology of infancy and childhood. ed 7. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier; 2009:1109-1217.