55 Leukemia

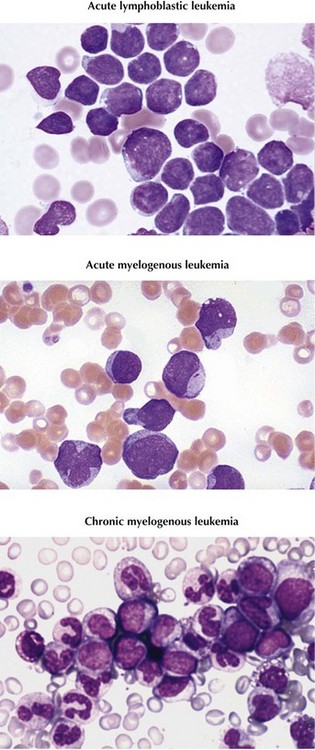

Leukemia is the most common type of childhood cancer, accounting for more than 3000 new cases annually and 25% of all malignancies diagnosed in patients younger than 20 years in the United States. Subtypes and prevalence include acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), 75%; acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), 20%; and chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), less than 5% (Figure 55-1). Other types of chronic leukemia, including those of lymphocytic and myelomonocytic cell lineages, are extremely rare in childhood.

Etiology And Pathogenesis

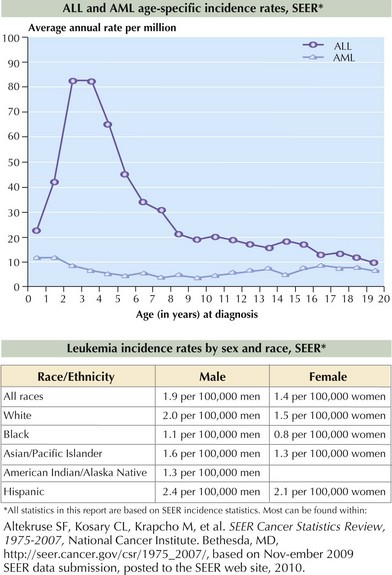

ALL occurs more frequently in boys and Caucasian children. The incidence peaks at 2 to 5 years, as shown in Figure 55-2. AML affects boys and girls equally, and pediatric incidence peaks in the neonatal and late adolescent periods (see Figure 55-2). In the United States, Hispanic and African American children are diagnosed with AML slightly more often than Caucasian children.

Genetics

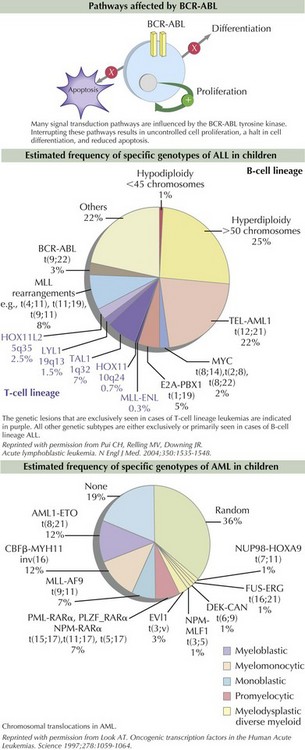

Some of the mutations are caused by chromosomal translocations resulting in fusion proteins that bring activated kinases and altered transcription factors together inappropriately. TEL-AML1 is the most commonly identified chromosomal translocation in pediatric ALL. TEL-AML1 t(8;21) is the product of the TEL gene responsible for recruiting progenitor stem cells into the bone marrow and the AML1 gene that plays a central role in hematopoietic cell differentiation. The Philadelphia chromosome is the product of a translocation of chromosomes 9 and 22, which is found in 95% of patients with CML and 2% of those with ALL. The translocation results in a fusion protein, BCR-ABL, which encodes a constitutively active tyrosine kinase protein. The tyrosine kinase activates proteins responsible for signaling within the cell cycle, therefore inducing uncontrolled cell proliferation, reducing apoptosis, and inhibiting DNA repair mechanisms (Figure 55-3). MLL, found on chromosome 11q23, partners with more than 40 genes and is found in childhood AML, secondary (or therapy-induced) AML, and the majority of infant ALL. Because the MLL gene arrangement is associated with several types of leukemia, specifically secondary AML after prior topoisomerase II inhibitor exposure, investigators are evaluating environmental topoisomerase II exposures that might be responsible for in utero mutations resulting in infant leukemia.

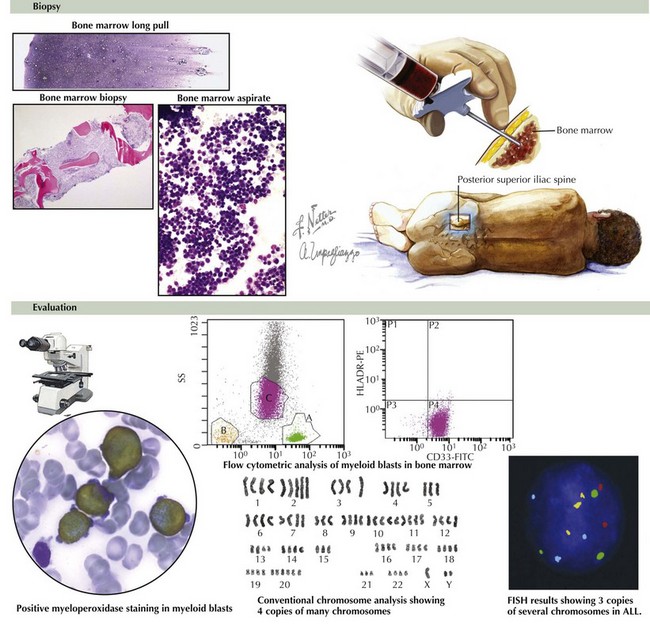

The process of cytogenetic profiling involves evaluating leukemic blasts for both the number of chromosomes and specific translocations (see Figure 55-3). This information is used to classify leukemia subtypes and give prognostic information and is often part of treatment risk stratification algorithms. For example, in pre–B-cell ALL, hyperdiploidy (>50 chromosomes) is associated with a good prognosis. However, hypodiploidy (<45 chromosomes) signifies a poor prognosis. Patients with AML are considered to have good-risk disease if the leukemia cell contains t(8;21) and inv(16) mutations. Other genetic abnormalities such as monosomy 5 and 7 and abnormalities of 3q are considered unfavorable. As many as 40% of patients with AML have activating mutations within the FLT3 gene, which are known as internal tandem duplications (ITDs). Both increased number of ITDs and location within the FLT3 gene are associated with poor clinical outcome.

Clinical Presentation

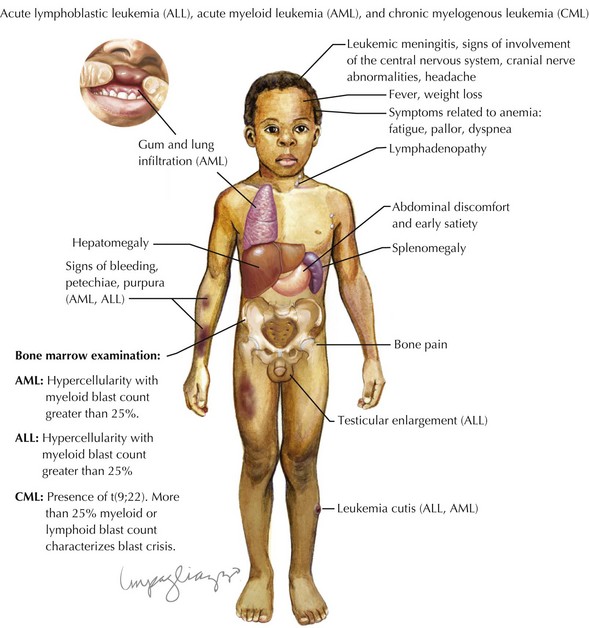

Children with leukemia primarily present with symptoms of bone marrow failure. The leukemia cells overpopulate the marrow and prevent normal growth of other hematopoietic cells. Signs and symptoms of anemia include fatigue, headache, pallor, and tachycardia. Thrombocytopenia often presents with petechiae and easy bruising, and leukopenia results in infection and fevers. The crowding of the bone marrow can also cause bony pain, often mistaken for “growing pains” in school-aged children (Figure 55-4).

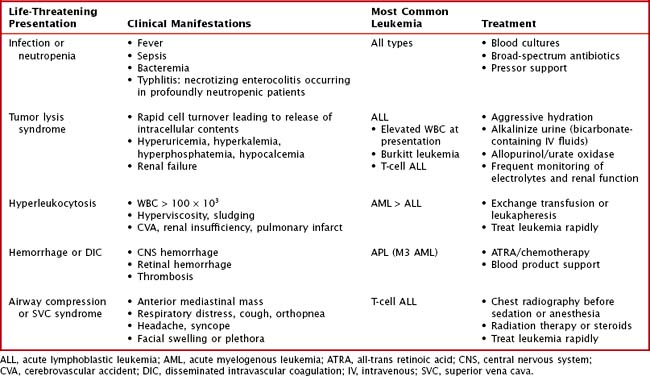

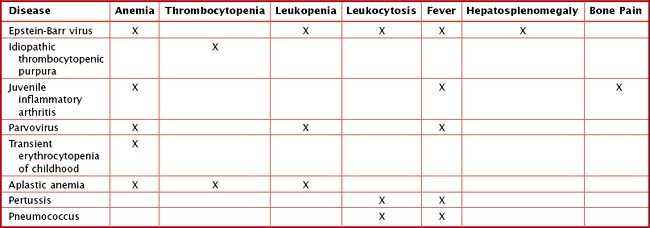

Other findings on physical examination are caused by leukemic infiltrate into normal tissues, such as the liver, spleen, lymph nodes, thymus, or testicles. The testicle is a common extramedullary site for ALL and may present as an enlargement of one or both testes. Leukemia cutis, or leukemic infiltration of the skin, has a varied presentation and may appear as single or multiple lesions commonly described as violaceous or hemorrhagic. Leukemia cutis most commonly presents in infant ALL and AML. Central nervous system (CNS) involvement at diagnosis is most often asymptomatic, but children with CNS disease may present with symptoms of increased intracranial pressure, visual disturbances, cranial nerve palsies, or gait disturbance. Other rare CNS effects not directly related to leukemic infiltration include intracranial hemorrhage and infarction. The presentation of CML can be very nonspecific and is often only suspected when a high white blood cell (WBC) count is seen on the complete blood count (CBC). Table 55-1 lists some of the life-threatening complications of leukemia at presentation and during therapy. Childhood leukemia presents similarly to many other common childhood illnesses (Table 55-2), and a bone marrow aspirate is necessary to make a definitive diagnosis.

Evaluation

Chest radiography should be performed before sedation or anesthesia is used to determine the presence of a mediastinal mass. A bone marrow aspirate and biopsy must be reviewed for morphology, immunohistochemistry, and cytogenetics (Figure 55-5). A lumbar puncture is also performed at diagnosis to determine the presence of leukemia within the CNS.

Classification

ALL is classified according to cell lineage as either B- or T-cell disease. B-cell disease is further categorized based on the level of differentiation of the B-cell involved (Table 55-3). Historically, the French-American-British (FAB) classification system divided ALL into three subtypes. Because this classification did not account for more sophisticated methods of immunophenotyping and cytogenetic profiling, it is no longer used. The FAB classification of AML is still in use and consists of subtypes M0 to M7 based on cell type and differentiation (Table 55-4).

Table 55-3 Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Subtypes and Frequency

| Subtype | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Early precursor B-cell | 60-65 |

| Precursor B-cell | 20 |

| Mature B-cell “Burkitt leukemia” | 3 |

| T-cell | 15 |

Table 55-4 Acute Myelogenous Leukemia Classification Based on Cell Type

| Subtype | Cell type | Details |

|---|---|---|

| M0 | Undifferentiated stem cells | Very rare in children |

| M1 | Immature myeloblasts | |

| M2 | Slightly matured myeloblasts | Accounts for 25%-30% pediatric AML |

| M3 | Promyelocytes (mature myeloblasts) | Also known as acute promyelocytic leukemia |

| M4 | Immature monoblasts | Also known as acute myelomonocytic leukemia; most common in children younger than 2 years of age |

| M5 | Monoblasts | Also known as acute monocytic leukemia; more common in children younger than 2 years of age |

| M6 | Erythroblasts | Also known as acute erythroblastic leukemia; very rare in children |

| M7 | Megakaryoblasts | Also known as acute megakaryoblastic leukemia |

AML, acute myelogenous leukemia.

Management And Prognosis

Bailey LC, Lange BJ, Rheingold SR, et al. Bone-marrow relapse in paediatric acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(9):873-883.

Belson M, Kingsley B, Holmes A. Risk factors for acute leukemia in children: a review. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115(1):138-145.

Campana D. Status of minimal residual disease testing in childhood haematological malignancies. Br J Haematol. 2008;143(4):481-489.

Gilham C, Peto J, Simpson J, et al. Day care in infancy and risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: findings from UK case-control study. BMJ. 2005;330(7503):1294.

Greaves MF, Maia AT, Wiemels JL, et al. Leukemia in twins: lessons in natural history. Blood. 2003;102(7):2321-2333.

Kantarjian H, Schiffer C, Jones D, et al. Monitoring the response and course of chronic myeloid leukemia in the modern era of BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitors: practical advice on the use and interpretation of monitoring methods. Blood. 2008;111:1774-1780.

Mullighan CG. Genomic analysis of acute leukemia. Int J Lab Hematol. 2009;31(4):384-397.

Pui CH, Robison LL, Look AT. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet. 2008;371(9617):1030-1043.

Pui CH, Relling MV, Downing JR. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(15):1535-1548.

Pui CH, Schrappe M, Ribeiro RC, et al. Childhood and adolescent lymphoid and myeloid leukemia. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2004;Jan:118-145.

Rubnitz JE, Gibson B, Smith FO. Acute myeloid leukemia. Pediatr Clinic of North Am. 2008;55(1):21-51.

Smith MA, Ries LA, Gurney JG, et al. Leukemia. In: Ries LAG, Smith MA, Gurney JG, et al, editors. Cancer Incidence and Survival Among Children and Adolescents: United States SEER Program 1975-1995, NIH Pub. No. 99-4649. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, SEER Program, 1999.