Chapter 212 Leptospira

Clinical Manifestations

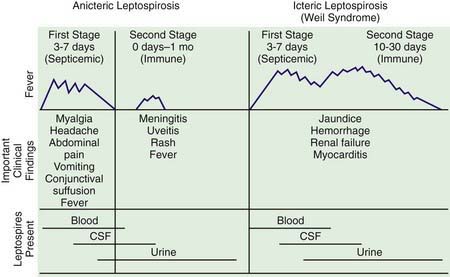

The spectrum of human leptospirosis ranges from asymptomatic infection (most cases) to severe disease with multiorgan dysfunction and death. The onset is usually abrupt, and the illness tends to follow a biphasic course (Fig. 212-1). After an incubation period of 7-12 days, there is an initial or septicemic phase lasting 2-7 days, during which leptospires can be isolated from the blood, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and other tissues. This phase may be followed by a brief period of well-being before onset of a second symptomatic immune or leptospiruric phase. This phase is associated with the appearance of circulating antibody, disappearance of organisms from the blood and CSF, and appearance of signs and symptoms associated with localization of leptospires in the tissues. Despite the presence of circulating antibody, leptospires can persist in the kidney, urine, and aqueous humor. The immune phase can last for several weeks. Symptomatic infection may be anicteric or icteric.

Bharti AR, Nally JE, Ricaldi JN, et al. Leptospirosis: a zoonotic disease of global importance. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:757-771.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Leptospirosis after flooding of a university campus—Hawaii, 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:125-127.

Heath CWJr, Alexander AD, Galton MM. Leptospirosis in the United States. Analysis of 483 cases in man, 1949–1961. N Engl J Med. 1965;273:857-864.

Jackson LA, Kaufmann AF, Adams WG, et al. Outbreak of leptospirosis associated with swimming. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1993;12:48-54.

Libraty DH, Myint KSA, Murray CK, et al. A comparative study of leptospirosis and dengue in Thai children. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2007;1(3):e111.

Meites E, Jay MT, Deresinski S, et al. Reemerging leptospirosis, California. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:406-412.

Sharma R, Tuteja U, Khushiramani R, et al. Application of rapid dot–ELISA for antibody detection of leptospirosis. J Med Microbiol. 2007;56:873-874.

Wang Z, Jin L, Wegrzyn A. Leptospirosis vaccines. Microb Cell Fact. 2007;6:39.

Wong ML, Kaplan S, Dunkle LM, et al. Leptospirosis: a childhood disease. J Pediatr. 1977;90:532-537.

Wuthiekanun V, Sirisukkarn N, Daengsupa P. Clinical diagnosis and geographic distribution of leptospirosis, Thailand. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:124-126.