Chapter 277 Leishmaniasis (Leishmania)

Clinical Manifestations

Localized Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

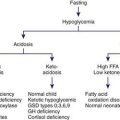

LCL (Oriental sore) can affect individuals of any age, but children are the primary victims in many endemic regions. It may present as 1 or a few papular, nodular, plaquelike, or ulcerative lesions that are usually located on exposed skin, such as the face and extremities (Fig. 277-1). Rarely, >100 lesions have been recorded. The lesions typically begin as a small papule at the site of the sandfly bite, which enlarges to 1-3 cm in diameter and may ulcerate over the course of several weeks to months. The shallow ulcer is usually nontender and surrounded by a sharp, indurated, erythematous margin. There is no drainage unless a bacterial superinfection develops. Lesions caused by L. major and L. mexicana usually heal spontaneously after 3-6 mo, leaving a depressed scar. Lesions on the ear pinna caused by L. mexicana, called chiclero ulcer because they were common in chicle harvesters in Mexico and Central America, often follow a chronic, destructive course. In general, lesions caused by L. (Viannia) species tend to be larger and more chronic. Regional lymphadenopathy and palpable subcutaneous nodules or lymphatic cords, the so-called sporotrichoid appearance, are also more common when the patient is infected with organisms of the Viannia subgenus. If lesions do not become secondarily infected, there are usually no complications aside from the residual cutaneous scar.

Visceral Leishmaniasis

VL (kala-azar) typically affects children <5 yr of age in the New World and Mediterranean region (L. infantum/chagasi) and older children and young adults in Africa and Asia (L. donovani). After inoculation of the organism into the skin by the sandfly, the child may have a completely asymptomatic infection or an oligosymptomatic illness that either resolves spontaneously or evolves into active kala-azar. Children with asymptomatic infection are transiently seropositive but show no clinical evidence of disease. Children who are oligosymptomatic have mild constitutional symptoms (malaise, intermittent diarrhea, poor activity tolerance) and intermittent fever; most will have a mildly enlarged liver. In most of these children the illness will resolve without therapy, but in approximately 25% it will evolve to active kala-azar within 2-8 mo. Extreme incubation periods of several years have rarely been described. During the 1st few weeks to months of disease evolution the fever is intermittent, there is weakness and loss of energy, and the spleen begins to enlarge. The classic clinical features of high fever, marked splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, and severe cachexia typically develop approximately 6 mo after the onset of the illness, but a rapid clinical course over 1 mo has been noted in up to 20% of patients in some series (Fig. 277-2). At the terminal stages of kala-azar the hepatosplenomegaly is massive, there is gross wasting, the pancytopenia is profound, and jaundice, edema, and ascites may be present. Anemia may be severe enough to precipitate heart failure. Bleeding episodes, especially epistaxis, are frequent. The late stage of the illness is often complicated by secondary bacterial infections, which frequently are a cause of death. A younger age at the time of infection and underlying malnutrition may be risk factors for the development and more rapid evolution of active VL. Death occurs in >90% of patients without specific antileishmanial treatment.

Alvar J, Aparicio P, Aseffa A, et al. The relationship between leishmaniasis and AIDS: the second 10 years. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:334-359.

Amato VS, Tuon FF, Siqueira AM, et al. Treatment of mucosal leishmaniasis in Latin America: systematic review. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:266-274.

Bern C, Adler-Moore J, Berenguer J, et al. Liposomal amphotericin B for the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:917-924.

Bern C, Hightower AW, Chowdhury R, et al. Risk factors for kala-azar in Bangladesh. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:655-662.

Chappuis F, Sundar S, Hailu A, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis: what are the needs for diagnosis, treatment and control? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:873-882.

Desjeux P. Prevention of Leishmania donovani infection. BMJ. 2011;342:60-61.

Murray HW, Berman JD, Davies CR, et al. Advances in leishmaniasis. Lancet. 2005;366:1561-1577.

Palatnik-de-Souza CB. Vaccines for leishmaniasis in the fore coming 25 years. Vaccine. 2008;26:1709-1724.

Reithenger R, Dujardin JC, Louzir H, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:581-596.

Sundar S, Cakravarty J, Agarwal D, et al. Single-dose liposomal amphotericin B for visceral leishmaniasis in India. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:504-512.

Tuon FF, Amato VS, Graf ME, et al. Treatment of New World cutaneous leishmaniasis—a systematic review with a meta-analysis. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:109-124.

Van Griensven J, Boelaert M. Combination therapy for visceral leishmaniasis. Lancet. 2011;377:443-444.