Chapter 1 Legal concepts for health professionals

INTRODUCTION

It is fundamental to the provision of a safe and competent service that the pharmacist has an understanding of the relevance of the law to the provision of that service. Within Australia, health law is made up of a range of legal concepts that derive from the common law, civil and criminal law, contract law, the regulation of industrial relations and agreements as well as the statutory arrangements between state, territory and federal governments. The obligations and responsibilities imposed through the federal government’s commitment to international treaties and declarations also impact significantly on the provision of pharmacy services within the Australian context.

SOURCES OF THE LAW

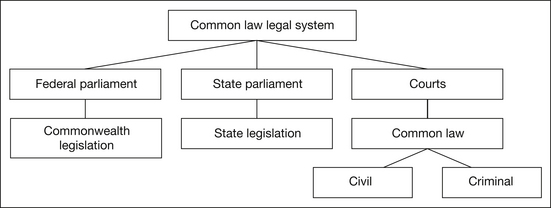

There are several different legal systems which operate throughout various countries around the world. As an example, there are countries which function under Islamic law, socialist law or Asian legal systems. Many European countries have a civil system, which was inherited from French or Roman cultures and is based on codes. One of the characteristics of a civil legal system is the inquisitorial nature of the trial process. This means the judge, rather than remaining impartial and making a decision based on the merits of a case argued before the court, will take an active role in investigating the facts and evidence. Unlike many European and Middle Eastern countries, Australia is described as a common law country (See Figure 1.1). This resulted from the colonisation of New South Wales by the British, who also operated under a common law system. The Australian legal system, and system of government, were thereby inherited as a function of British colonisation and have continued to develop post-federation into the systems as they exist today. As a common law country there are two sources of law under the Australian system. The first is legislation passed by the parliaments at both the state and federal levels. The second source is the common law that has developed from judicial decisions handed down by the courts.

Legislation — parliamentary law

Prior to the formation of the Commonwealth of Australia on 1 January 1901 the self-governing colonies operated independently and passed legislation through their own individual parliaments and, for some, under their own Constitution. The passage of the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900 (the Constitution) by the British government established the Commonwealth of Australia. The Constitution gave the Commonwealth Parliament the power to make laws either exclusively or concurrently with the states. Under the Constitution, the state parliaments retained their power to make laws as they had done prior to federation, unless the power to make laws about a specific matter had been given exclusively to the Commonwealth. Section 107 of the Constitution states:

Each of the federal, state and territory parliaments, through their individual constitutions, may pass laws for the ‘peace, and good government’[1] of the jurisdiction.

The federal, state and territory parliaments are therefore empowered to enact legislation, also known as Acts or statutes, for the purpose of regulating certain aspects of society. An Act, passed by the parliament elected by the people, is a primary source of the law and has priority over the common law, which is derived from court decisions. That is, legislation takes precedence over judge-made law (case law) and while it is not the role of the court to make laws where the same subject matter is covered by an Act, it is the role of the court to interpret legislation that is relevant to the determination of the case that is before it. Some states and territories will also have codes which are a complete statement of the law in a particular area. Legislation can be accessed online through the state, territory or Commonwealth government websites.

International law

Australia, along with many other nations, is a signatory to a number of international declarations, covenants and treaties and is therefore bound to pass domestic legislation that is consistent with the obligations imposed under these international agreements. As an example, the laws in Australia regulating the importation, export and manufacture of medicines and poisons will be consistent with the provisions of declarations and covenants to which the Commonwealth is a signatory. As an example, the Free Trade Agreements between Australia and countries such as New Zealand, Singapore, Thailand, Chile and the United States impact on the terms of exportation and importation of pharmaceutical products.

STATUTORY INTERPRETATION

When reading legislation the focus must be on the actual language used. Examples of words that mandate a particular activity or status include will, shall or must. However, the use of a word such as may indicates a discretionary power. It is important when attempting to interpret an Act that the legislation is read as a whole so as to obtain the context of the words used. Explanatory notes, that sometimes accompany the Act and associated regulations, may also assist in resolving any ambiguity or clarifying the intention of the law. Statutory interpretation is now governed by various state, territory and Commonwealth Interpretation Acts.[2] Section 15AA (1) of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth) states:

Reading an Act

Regulations

One of the last sections in an Act confers on the Governor or Governor-General the power to make regulations that may be necessary for the administration of the Act. Regulations provide the essential details of administration that may change more frequently than the Act can be amended by parliament. Regulations are used to set fees and charges as well as a variety of requirements necessary to enable the daily implementation of the Act. The regulations are called delegated legislation (refer to ‘Delegated legislation’ at p 4). Regulations are drafted usually in the Attorney-General’s Department, advised by the department responsible for administering the Act. The regulations are tabled in parliament but they do not progress through parliament in exactly the same manner as an Act.

Common law

The law as it was imposed by England and Wales at the time of colonisation is referred to as common law. In addition to the use of the term to describe a legal system (comprising case law and statute law) it also describes a system of law that developed in the King’s courts from the 10th century through the accumulation of decisions made by judges in cases that came before them. Through the recording of principles and judgments in law reports there developed a body of case law and principles that could be referred to and followed. This practice, of following earlier decisions, is known as the doctrine of precedent and served to provide a level of certainty and predictability in the law.

TYPES OF LAW

THE AUSTRALIAN LEGAL SYSTEM

Adversarial and inquisitorial system

One of the functions of the law is to resolve disputes when conflicts arise between individuals, companies and institutions. The resolution of a conflict can take place through alternate dispute resolution mechanisms or through the court process. If resolution is sought through the courts the case will be brought before a magistrate, judge, or judge and jury with the expectation that the issues in dispute will be resolved and that there will be a declared ‘winner’. This competition between the parties that takes place within the courts is referred to as the adversarial process. There are very strict rules as to how this process is conducted and what are the roles, functions and obligations of all those who participate in this process. The role of the judge during court proceedings is to remain impartial and to ensure that the procedural rules are adhered to. The judge or jury will determine the outcome, where only one of the parties to the proceedings will be successful. This is different from the inquisitorial approach where the court may become a participant in the actual process.

Natural justice

In a general sense it ensures that the proceedings are conducted fairly, impartially and without prejudice. Natural justice is a fundamental principle that applies to all courts and tribunals. It is described as making two demands before an individual’s legal rights are adversely affected, or their rightful expectations disappointed; first, to show why any adverse action should not be initiated and, second, that the decision-maker comes to the decision with an open and unbiased mind.[3]

The doctrine of precedent (stare decisis)

In the discussion of common law, mention was made of the role of judges in making law. The word ‘common’ is used to denote the fact that judges have developed a process whereby courts are, to a certain extent, bound to follow decisions they have made previously as well as being bound by decisions made by other judges at the same level of the hierarchy or in senior courts. Judge-made law, or common law, began as a custom that valued the accumulation of judicial wisdom passed on through the ages. In this way a common thread of judicial certainty was maintained despite different judges presiding. Early in the 19th century this custom became enshrined as a doctrine known as stare decisis or the ‘doctrine of precedent’. It allows for some predictability when dealing with legal matters involving courts because one is able to determine the outcomes of similar cases that have occurred before, and estimate the probability of similar judgments being passed.

The court hierarchy

Original and appellate jurisdiction

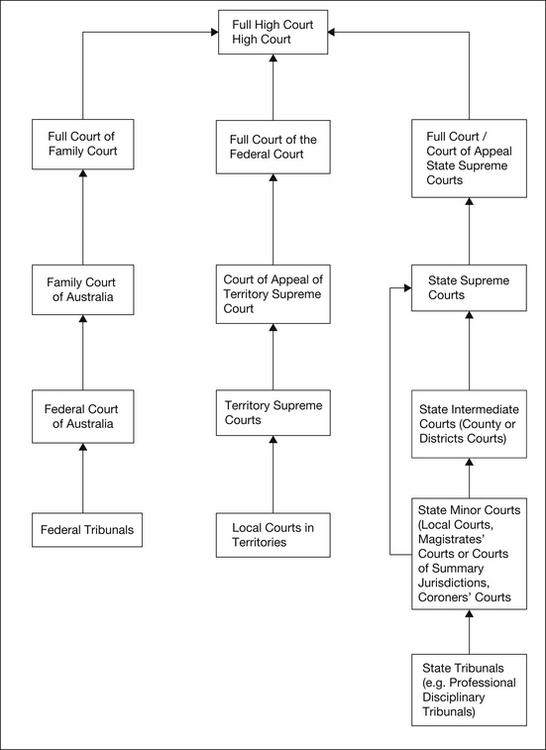

When a matter first arises, the court in which it is heard has what is known as original jurisdiction. Before a decision may be appealed in another court the dissatisfied party must be able to establish appropriate grounds. If this is established the subsequent court will be exercising its appellate jurisdiction. A decision may be the subject of an appeal in certain circumstances including: when a judge has misdirected a jury, made an error in relation to admitting or refusing to admit evidence, or there is an issue as to the severity or leniency of the sentence. For example, the District or County Court may hear a matter and, if a party appeals that decision, the Supreme Court will hear the matter using its appellate jurisdiction. Appellate jurisdiction is restricted to the superior courts including the District/County Court, Supreme Court, Federal Court, Family Court and High Court. In relation to the High Court, special leave (permission) must be sought before it will exercise its appellate jurisdiction. Figure 1.2 provides an overview of the court hierarchy, to illustrate the differences in both structure and jurisdiction of the courts in the hierarchy.

Magistrates’ Courts

Magistrates’ Courts or local courts are presided over by magistrates who are addressed during the proceedings as ‘Your Worship’ or ‘Your Honour’. Magistrates sit alone as there are no juries at this level in the court structure. The jurisdiction of the Magistrates’ Courts is determined by the relevant legislation in each of the states and territories. These courts are the lowest courts in the hierarchy and determine the greatest volume of cases. As a general principle Magistrates’ Courts deal with minor civil and criminal matters, and with more serious criminal matters by way of committal proceedings. It is from this level of the hierarchy that magistrates are appointed as coroners or preside over Children’s Courts and Licensing Courts. These courts developed in response to the need to reduce the load from the Magistrates’ Courts and in recognition of the requirement for specialist knowledge.

The Federal Court

The Federal Court of Australia was established under the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth). This court was set up to further reduce the load on the High Court. Constitutional cases involving such matters as trade practices, bankruptcy and federal industrial disputes are heard. Appeals on decisions can be made to the High Court or the Full Court of the Federal Court.

CASE REFERENCES

Law reports

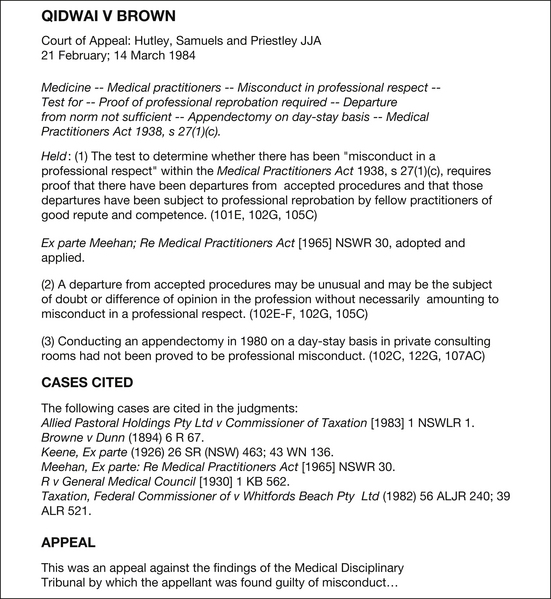

For a health professional to understand the common law principles that apply to their practice it is necessary to have the skills to read a case as reported. Figure 1.3 provides an overview of the features of the case of Qidwai v Brown [1984] 1 NSWLR 100.

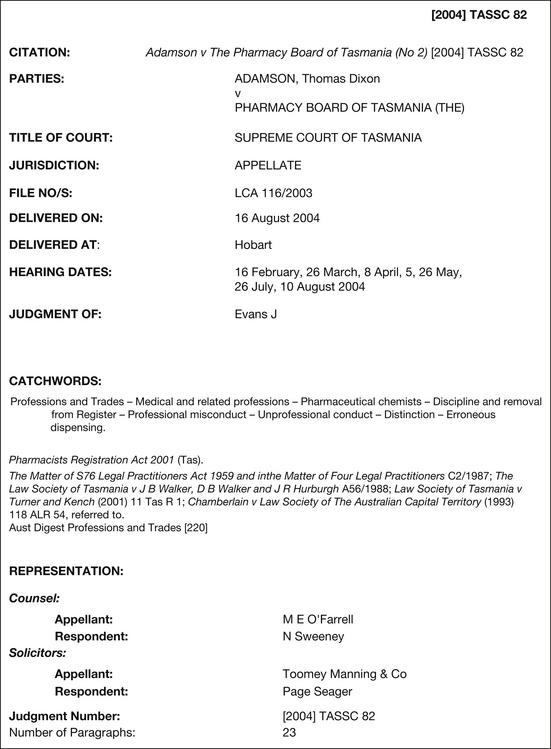

As can be seen from Figure 1.4, while the formatting of web-based case reports may differ from the previous paper-based law reports, the information provided is essentially the same. The wide range of electronically based legal resources now available facilitates greater access to, and understanding of, the law. Knowledge of the Australian legal system and the legislation and case law that regulates the provision of pharmacy practise is essential to the provision of safe and competent pharmacy services.

Carvan J. Understanding the Australian Legal System, 5th edn. Sydney: Law Book Co; 2005.

Chisholm R., Nettheim G. Understanding Law: an Introduction to Australia’s Legal System, 6th edn. Sydney: Butterworths; 2002.

Hinchy R. The Australian Legal System: History, Institutions and Method. Sydney: Pearson Education Australia; 2008.

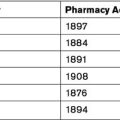

2 Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth); Interpretation Act 1987 (NSW); Interpretation of Legislation Act 1984 (Vic); Acts Interpretation Act 1915 (SA); Interpretation Act 1984 (WA); Interpretation Act 1967 (ACT); Acts Interpretation Act 1954 (Qld)

3 Forbes J.R.S. Justice in Tribunals, 2nd edn. Sydney: The Federation Press, 2006. 100