Leadership

Introduction

This chapter takes a broad look at leadership, a principle of organizational development that has been debated and studied for over 50 years. During this time the theories have changed considerably (Huczynski & Buchanan 2003, Bass & Bass 2008, Lang & Rybnikova 2012); however, one thing has remained consistent, human behaviour is a fundamental part of leadership. It is also clear that in an increasingly political healthcare environment strong clinical leadership is essential for effective patient care, and for nurses’ well-being. This chapter will look at some aspects of leadership behaviour and identify the key components of effective clinical leadership as well as some of the principles of clinical supervision.

What is leadership?

Leadership is a much debated term with many conflicting theories, definitions and qualities to describe successful leaders (Wade-Grimm 2010). Most people recognize a good leader, but it is often harder to identify why that individual is a good leader. It does, however, differ from management in that specific status or organizational position is not necessary for an individual to be a leader. So, if position is not the key factor, what is? Skills are important, but not necessarily the ones that may be expected. For example, management skills, attention to detail, organization, intelligence and planning are not consistent among great leaders (Owen 2005). The same inconsistencies exist when considering styles of leadership. Where consensus does exist it is around a collection of behaviours that together can create a leader; these include honesty and integrity, the ability to motivate others, vision, decisiveness, confidence and intuition. In short, leadership is the ability to influence others without threat or coercion (Huczynski & Buchanan 2003).

In healthcare, the profile and priority given to effective leadership has grown slowly, but its importance continues to increase, along with the evidence base showing how powerful effective leadership can be (Young-Ritchie et al. 2010). Effective leadership should not be confused with good management; the two often co-exist, but can also come from two different sources, as the behaviours demonstrated by leaders are not absolutely necessary for effective management.

Management can be seen as the organizational and technical tasks that have to be achieved in order to ensure the fluid delivery of services. Management is head-driven, rational and pragmatic. Leadership can be seen as the inspiration of others, the skills employed, often subtly, to galvanize a group of staff to commit to deliver a quality service. Leadership is heart-driven, emotive and enthusing. The most effective environments have both, and both leaders and managers are most effective when able to use a range of behaviours and skill from each domain, depending on circumstances.

Clinical leadership

Leadership skills are essential in any clinical environment, and the nature of Emergency Department (ED) work is such that priorities and pace can change dramatically over a very short period, with a potential for staff to feel threatened by the perceived chaos. To maintain a safe, effective service to patients the clinical leader needs to foster an environment where care delivery has some structure, staff have guidance and security, therefore trust can develop (Jonas et al. 2011). These rapidly changing high-pressured clinical areas are the environments where leadership and management are mostly likely to intertwine. It is not uncommon for the management role to become dominant, resulting in both perceived leaders and their clinical staff feeling disempowered and demoralized with their work. For clinical leadership to be successful, and not just clinical management, an overarching environment where individuals feel empowered and able to develop relies on access to information, power, opportunity and resources (Upenieks 2003). It is only when individuals feel empowered that they can truly lead change, take risks and create the innovation needed to develop clinical care.

The challenge for those leading care on a day-to-day basis in emergency care environments can seem daunting alongside the practical tasks of managing the workload, but often what is required is conscious application of principles used every day. Stanley (2006) discusses the value of congruent leadership as a basis for developing clinical care and describes clinical leaders as individuals who are experts in their field, positive clinical role models and good communicators. They are followed because they can translate what they believe about nursing into good clinical care. This is in fact a simple phenomenon; congruent leaders are successful because their values and beliefs and their actions match up; as a result they are credible.

Effective clinical leaders can adapt congruence theory to enhance their current practice. It creates a bridge between the necessary management role and the desired leadership role. The most important component in creating congruence is passion; this comes from trusting, valuing and believing in what you are doing (Thompson 2000).

Congruent leadership can be summed up as leading from the heart, trusting your instincts, and valuing your knowledge and beliefs (Box 36.1).

Step 1: how you feel It is no accident this is step one, and in the clinical environment nurses do this all the time; they get a feel for when a patient is ‘going off’ or when they should be wary or feel threatened by some patients and not others displaying similar behaviour. This can be explained as intuition, sixth sense, or tacit or expert knowledge (Benner 1984, Benner et al. 2009). The key is to trust these feelings and act in congruence with them; they are based on both experience and intrinsic beliefs. Leadership behaviour will appear natural and confident, fostering trust and motivation to comply, as opposed to ignoring ‘feelings’, which can have the reverse effect on leadership behaviour, leaving the leader and the followers feeling anxious and lacking in confidence.

Garbett (1995) described leaders as people who have a vision; they make things happen, and at the same time they strengthen and support their followers, inspiring them to trust the leader. These appear to be the core qualities needed to lead the clinical team in ED.

Developing personal leadership behaviour

There are four key components to leadership behaviour:

Self-awareness

Personal effectiveness stems from self-awareness. It is only through true understanding of her/his strengths, likes and dislikes that a leader can find an authentic set of leadership behaviours. Through self-awareness the leader can understand what makes her/him feel strong or vulnerable, where she/he feels effective and where she/he is less sure, and what she/he is confident about. It is also through self-awareness that a leader can examine her/his expectations, and beliefs about herself/himself. Many individuals are far better at criticizing themselves than celebrating their strengths; this is probably the single most effective way of undermining self-confidence (Gonzalez 2012). Often this internal criticism is based on long-held beliefs and expectations that have no genuine validity. Once the leader becomes aware of this behaviour he/she is better placed to reverse it and replace negative internal dialogue with positive comments and praise for what is good. Box 36.2 offers some areas for self-examination to enhance self-awareness.

It is only with self-awareness that a leader can really understand the impact of her/his behaviour on others, as well as what expertise she/he needs from other team members to enhance the team. It is also worth remembering that behaviours individuals dislike in themselves they usually dislike in others, so a self-aware leader will be able to head off potential conflict by understanding where those feelings come from. An effective leader is someone who not only understands herself/himself well, but is also willing to challenge her/his make-up and change their viewpoint (Welford 2002). The dogmatic leader may appear strong and purposeful but will often close their minds to alternatives that may actually be better.

Positivity

Leaders are positive in their attitudes, their direction and their responses. Being positive is not down to chance or personality, it is learned behaviour. Being positive is about creating solutions and learning to be lucky. Being lucky is an attitude, a way of behaving, and a way of seeing the world. Fundamentally, individuals create their own luck, and appearing lucky to others is often down to sheer hard work and creating enough opportunities (Box 36.3).

Communication

Becoming a clinical leader is a time of great personal vulnerability. The leader’s knowledge, ability to organize and sustain direction, and skills in supporting others will all come under scrutiny before followers decide to adopt the leader’s vision. Effective communication is fundamental to gaining acceptance as a leader. Most ED nurses have experienced a shift where the nurse in charge keeps information about patient progress to him- or herself and does not keep staff informed of activity. This results in a withdrawal from the situation; nurses continue to function under direction, but they have no ownership of the activity and offer little support to the leader. Conversely, where communication is good and ideas are welcomed from other nurses, staff work as a team, supporting each other and the leader. The success relies on the ability to communicate effectively with other staff members. This means the leader is able to give direction and feedback to staff, but also can receive feedback, air ideas and develop strategy (Box 36.5).

Empowerment

Empowerment does not mean a lack of managerial control. The clinical leader must set boundaries on what are acceptable standards and behaviours and what are unacceptable. These must be communicated to others in the clinical environment and should remain constant. This way the team is free to participate in decision-making within a preset structure. For most people, boundaries provide a sense of stability and security. This can be particularly important when trying to maintain a departmental direction and vision. Leadership, however, is as much about risk-taking as it is about control. The effective leader will allow her team to make decisions that may be inappropriate or less than efficient (Bowles & Bowles 1999). The risk that should be considered, balanced and judged is whether the consequences of the staff making the wrong decision will be catastrophic. If this is likely then the leader would be foolish not to make a decision and pass it on; if it will not be then it may be worth allowing others to make the choice and let them glory in their success or learn from their lesson, depending on how things turn out. It might be easier as a leader to just take control and make the decisions; there is little risk of things going wrong, particularly in a busy ED. This fails, however, to empower the team. This lack of empowerment and overly controlling approach can lead to disenfranchisement of staff from the organizational process of their department, simply turning up at work to do their job; or worse the team become so disempowered that staff become unable to make even the most basic and simple of decisions. Every leader must remember that if there is constant downward management there will be constant upward referral. This does nothing to develop the skills of others and is exhausting for the leader. The challenge for the leader is one of balance; in order to empower and develop staff they must feel trusted, capable and supported. In order to achieve this, the leader must feel comfortable with the degree of risk he/she is taking.

Team-building

There are a number of systems available to analyse the personality profiles of individuals. It can be helpful to undertake such analysis in order to appreciate where the strengths lie within a team (Dolan 2011). By understanding this, the allocation of tasks can be made based upon people’s strengths, so ensuring the best outcome. The effective leader, however, will also use such understanding to identify where an individual’s weaknesses lie and sometimes allocate tasks to stretch and develop skills. This can be an uncomfortable experience for the individual that may result in resistance to the leader. The leader must, therefore, ensure that such development is backed up with support, reassurance and positive feedback.

A crucial factor in team-building is the function of the leader. To be successful, this person must remain part of the team, giving direction and support to the other team members. The leader must be secure enough in her/his own knowledge to encourage and utilize the abilities and knowledge of other team members without being threatened. It is important for leaders to recognize their own limitations, but recognition is not sufficient. Declaration of one’s own limitations can often encourage loyalty and affiliation to the leader by the followers. This must be undertaken positively and with care and judgement. Listening effectively to the views and opinions of others, while acknowledging one’s own short-comings, can lead to better decisions and a stronger team (Caplin-Davies 2000).

Political savvy

As a professional group, nurses are often less aware of how to manage organizational politics than other professional groups in healthcare (Nelson & Gordon 2006). This can have a detrimental effect on leadership ability. The principles of influence are the same regardless of the target audience, so whether the Chief Executive, Director of Nursing or Healthcare Assistant is the person to be influenced, the following principles apply.

Clinical leaders should use charm in the same way many medical colleagues do; it will engage others, make them want to talk, and more importantly listen to others’ views (Box 36.6).

Leadership is fundamentally about influence; it is worth thinking about the impact clinical leaders make as individuals to ensure it is the impact they want to make (Armstrong 2012).

Clinical supervision

The importance of clinical supervision was emphasized in the light of serious concerns identified by the Allitt Inquiry (1991), named after Beverly Allitt, a paediatric nurse in England who assaulted 13 children in her care, murdering four during the early 1990s. The Health Service Ombudsman at that time repeatedly raised concerns about a number of flaws identified in the delivery of nursing care, including the quality of record-keeping. Clinical supervision offered a potential solution to some of the difficulties being encountered by the nursing profession on an individual and organizational basis. Some areas of nursing, such as psychiatry, have used supervision for many years; however, in acute nursing the concept has been underdeveloped.

The King’s Fund (1994) has described clinical supervision as a formal arrangement in which nurses can discuss work with another professional colleague. It has been promoted as a support mechanism for nurses, a tool for professional development and a method of quality control.

Principles to support clinical supervision

The Nursing and Midwifery Council (2002) supports the concept of clinical supervision, however it has stopped short of identifying any particular model of delivery to allow for local adaptation. It does stipulate a set of guiding principles that should be used (Box 36.7).

These activities all involve interaction with others, such as patients and their relatives or friends, and are not without personal risk. In emergency care, the patient’s stay is relatively short and the onus is on the nurse to develop a therapeutic relationship quickly, but how do nurses maintain this relationship when someone is off sick, the shift is busy or the relative has complained about the ever-increasing waiting times?

Types of supervision

• one-to-one supervision with an expert from a nursing or related background

• one-to-one supervision within a peer group

Peer supervision means the supervisor and supervisee are involved in similar clinical work, and possibly face similar challenges. The advantages are increased awareness, potentially greater trust and a relationship that is less threatening to the supervisee. The disadvantage is that without effort and commitment from both parties, the activity can become purely one of support and not development. Group and network supervision have been developed in some areas of healthcare, particularly in community settings. This involves a group of similar professionals sharing experiences and developing their practice using one another. For this to be successful, a large degree of trust and commitment is needed from participants. It does have disadvantages in that some members of the group can remain non-participative or dominate activity. It is perhaps organizationally easier to facilitate than one-to-one supervision. Whichever method of supervision is adopted, it is essential that the clinical supervisor remains clinically challenging. The success of clinical supervision relies on its perceived value to the department (Jones 2006); therefore agreeing the aims and process before implementation is imperative. Bishop (1994) identifies three overall aims that act as a bedrock for supervision activities:

To achieve these objectives, clinical supervision should be seen as a continuum along with mentorship and preceptorship. A mentor helps to develop clinical competence by guiding a nurse through learning a new skill, such as cannulation. A preceptor helps the nurse gain confidence in that role. A clinical supervisor aids professional development from acquisition of new skills. But for clinical supervision to be successful it is important to consider the impact of the nurse as a whole and not as a technician.

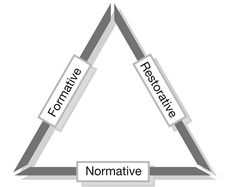

The philosophical approach to clinical supervision does not have to be complicated. Proctor (1986) suggested a simple tripartite approach to supervision (Fig. 36.1). The formative role is one of education, supplementing the supervisee’s knowledge and facilitating growth. The restorative aspect relies on support, exploring anxieties or critical incidents and allowing the supervisee to resolve stress. The normative function is one of quality control, looking at actual practice and challenging methods to maintain high standards of patient care.

Figure 36.1 Functions of clinical supervision.

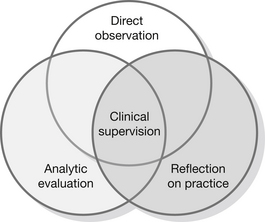

The success of clinical supervision relies on its perceived value to the department and staff commitment. The activities of clinical supervision revolve around the provision of regular space for reflection on the content and process of work (Fig. 36.2). Its functions are to develop the understanding and skills of the supervisee, to ensure quality nursing care and to provide space to explore and express distress about work. Done effectively this will result in the supervisee feeling valued and validated both as a person and as a nurse, as she/he is able to receive feedback and therefore gain new perspectives on her/his work. This empowers the nurse to plan and utilize personal resources and become proactive and innovative. Clinical supervision should not be a forum for self-congratulation or self-destruction, nor should it be personal therapy. The supervisor can facilitate this by observation of practice, encouraging retrospective reflection and participation in evaluating outcomes (RCN 2000).

Figure 36.2 Activities of a supervisor.

Getting clinical supervision

Before clinical supervision is established in a department, its ground rules should be identified and agreed by participants (Simms 1993); for example, it should be agreed that any unacceptable breach of the Code of Professional Conduct (Nursing and Midwifery Council 2008) may need to be taken outside the supervisory relationship (Box 36.8).

In addition to these, some practical considerations such as the frequency and length of meetings, criteria for supervisors and termination routes if sessions become destructive should all be agreed. A robust audit tool is useful to measure quantitative data about activity such as the frequency and duration of supervision sessions. Evidence of its value to nurses is largely subjective, but potential benefits are outlined in Box 36.9.

There remains much debate about the real value of clinical supervision. Shanley & Stevenson (2006) argue that it is potentially hazardous in its current form, and models need to become more sophisticated if they are to be successful. Despite the ongoing concern in acute and primary care, clinical supervision has been successful in mental health nursing for many years.

360 degree feedback

In this chapter self-awareness has been discussed in relation to leadership skills. Becoming self-aware is something that most people have to constantly work at developing. Getting feedback from other people is a critical part of this and giving feedback is an important part of being a leader. Very often this only happens when something has gone wrong, but feedback about strengths and things done well is equally as important and often leads to greater personal growth and performance improvement. The 360 degree feedback model is a good way of getting this type of information. It is popular for both clinicians and managers in the health sector. 360 degree feedback is where an individual (the appraisee) receives feedback from a selection of people, such as seniors, peers and juniors, in a range of predetermined competency areas (Holt 2011). While 360 degree feedback is predominantly a development tool, it can be used as part of a formal appraisal process, or in isolation. It is particularly valuable because it examines more than one work relationship and the impact the appraisee has in a number of different roles (Box 36.10).

Most people put a lot of time and emotional energy into their 360 degree feedback, and managed properly it is a motivating, powerful and positive experience. Managing 360 degree feedback properly takes time, effort and care, before, during and most of all afterwards. This way the organization, big or small, gets return on its 360 degree investment (Holt 2012).

Conclusion

This chapter has identified a range of clinical leadership and supervision issues which emergency nurses should consider when developing themselves and their practice. In an increasingly complex emergency service, support for and by those responsible for developing services is needed in order to recruit, retain and value that most precious commodity – the staff. The chapter highlights the importance of effective clinical leadership, both for those working within the ED environment and for their benefit within the organization. The chapter reinforces the need for clinical leaders to become more aware of professional and organizational politics, in order to get the best results for their clinical environment, those working in it and their patients. Finally, the chapter identifies that leaders exist at all levels within an organization, and because leadership is learned behaviour anyone can become a leader with a bit of self-awareness, willingness to stand out from the crowd, and the ability to influence others.

References

Allitt Inquiry. Independent Inquiry Relating to Deaths and Injuries on the Children’s Ward at Grantham and Kesteven General Hospital During the Period February to April 1991. London: HMSO; 1991.

Armstrong, H. Spirited Leadership: Growing Leaders for the Future. In: Roffey S., ed. Positive Relationships: Evidence Based Practice Across the World. New York: Springer, 2012.

Bass, B.M., Bass, R. Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research & Managerial Applications, fourth ed. New York: Free Press; 2008.

Benner, P. From Novice to Expert: Excellence and Power in Clinical Nursing Practice. Menlo Park: Addison-Wesley; 1984.

Benner, P., Tanner, C., Chesla, C. Expertise in Nursing Practice: Caring, Clinical Judgment, and Ethics, second ed. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2009.

Bishop, V. Clinical supervision for an accountable profession. Nursing Times. 1994;90(39):35–37.

Bowles, N., Bowles, A. Transformational leadership. Nursing Times Learning Curve. 1999;3(8):2–4.

Caplin-Davies, P. Nurse manager: Change thyself. Nursing Management. 2000;6(9):16–20.

Dolan, B. How to work with people you’d rather kill!. Nursing Review. 2011;12(1):11.

Garbett, R. Leading questions. Nursing Times. 1995;91(27):26–27.

Gonzalez, M. Mindful Leadership: The 9 Ways to Self-awareness, Transforming Yourself and Inspiring Others. Ontario: John Wiley & Sons Canada Ltd; 2012.

Holt, L. How to get the best ROI from 360 feeedback in your organization. The Grapevine. 2011;3:18–19.

Holt, L. Get Out of Your Own Way: Stop Sabotaging Your Business and Learn to Stand Out in a Crowded Market. London: NABO (UK) Ltd; 2012.

Huczynski, A., Buchanan, D. Organisational Behaviour: An Introductory Text, fifth ed. London: Prentice Hall; 2003.

Jonas, S., McCay, L., Keogh, B. The importance of clinical leadership. In: Swanwick T., McKimm J., eds. The ABC of Clinical Leadership. London: BMJ Publishing, 2011.

Jones, A. Clinical supervision: what do we know and what do we need to know? A review and commentary. Journal of Nursing Management. 2006;14(8):577–585.

King’s Fund. Clinical Supervision: An Executive Summary. London: King’s Fund Centre; 1994.

Lang, R., Rybnikova, I., Leadership is going global. Benscoter, G.M., eds. The Encyclopaedia of Human Resource Management, vol. 3. San Francisco: Pfeiffer Books, 2012.

Nelson, S., Gordon, S. Moving beyond the virtue script in nursing. In: Nelson S., Gordon S., eds. The Complexities of Care: Nursing Reconsidered. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2006.

Nursing and Midwifery Council. Supporting Nurses and Midwives Through Life-long Learning. London: Nursing and Midwifery Council; 2002.

Nursing and Midwifery Council. Code: Standards of conduct, performance and ethics. London: Nursing and Midwifery Council; 2008.

Owen, J. How to Lead. Edinburgh: Pearson Education Ltd; 2005.

Proctor, B. Supervision: a co-operative exercise in accountability. In: Marken M., Payne M., eds. Enabling and Ensuring. Leicester: Leicester Youth Bureau and Council for Education and Training in Youth and Community Work, 1986.

Royal College of Nursing. Ground Rules and Responsibilities for Clinical Supervision. London: RCN; 2002.

Shanley, M.J., Stevenson, C. Clinical supervision revisited. Journal of Nursing Management. 2006;14(8):586–592.

Simms, J. Supervision. In: Wright H., Giddey M., eds. Mental Health Nursing. London: Chapman & Hall, 1993.

Stanley, D. Recognizing and defining clinical leaders. British Journal of Nursing. 2006;15(2):108–111.

Thompson, C.M. A Congruent Life. San Francisco: Jossey Bass Publications; 2000.

Upenieks, V. Nurse leaders’ perceptions of what compromises successful leadership in today’s inpatient environment. Nursing Administration Quarterly. 2003;27(2):140–152.

Wade-Grimm, J. Effective leadership: Making the difference. Journal of Emergency Nursing. 2010;36(1):74–77.

Welford, C. Transformational leadership – matching theory to practice. Nursing Management. 2002;9(4):7–11.

Young-Ritchie, C., Spence Laschinger, H.K., Wong, C. The effects of emotionally intelligent leadership behavior on emergency staff nurses’ workplace empowerment and organizational commitment. Nursing Research. 2010;22(1):171–194.