Chapter 702 Lead Poisoning

Sources of Exposure

Several hundred products contain lead, including batteries, cable sheathing, cosmetics, mineral supplements, plastics, toys (Table 702-1), and traditional medicines (Table 702-2). Major sources of exposure vary among and within countries; the major source of exposure in the USA remains old lead-based paint. About 38 million homes, mainly built before 1950, have lead-based paint (2000 estimate). As paint deteriorates, it chalks, flakes, and turns to dust. Improper rehabilitation work of painted surfaces (e.g., sanding) can result in dissemination of lead-containing dust throughout a home. The dust can coat all surfaces, including children’s hands. All of these forms of lead can be ingested. If heat is used to strip paint, then lead vapor concentrations in the room can reach levels sufficient to cause lead poisoning via inhalation.

Table 702-2 CASES OF LEAD ENCEPHALOPATHY ASSOCIATED WITH TRADITIONAL MEDICINES BY TYPE OF MEDICATION

| TRADITIONAL MEDICAL SYSTEM | CASES OF LEAD ENCEPHALOPATHY N (%) | N (%) PEDIATRIC CASES WITHIN CAM SYSTEM OR MEDICATION |

|---|---|---|

| Ayurveda | 5 (7) | 1(20) |

| Ghasard | 1 (1) | 1 (100) |

| Traditional Middle Eastern practices | 66 (87) | 66 (100) |

| Azarcon and Greta | 2 (3) | 2 (100) |

| Traditional Chinese medicine | 2 (3) | 2 (100) |

| Total | 76 (100) | 72 (95) |

CAM, complementary and alternative medicines.

From Karri SK, Saper RB, Kales SN: Lead encephalopathy due to traditional medicines, Curr Drug Safety 3:54–59, 2008.

Clinical Symptoms

Gastrointestinal Tract and Central Nervous System

Other organs also may be affected by lead toxicity, but symptoms usually are not apparent in children. At high levels (>100 µg/dL), renal tubular dysfunction is observed. Lead may induce a reversible Fanconi syndrome (Chapter 523). In addition, at high BLLs, red blood cell survival is shortened, possibly contributing to a hemolytic anemia, although most cases of anemia in lead-poisoned children are due to other factors, such as iron deficiency and hemoglobinopathies. Older patients may develop a peripheral neuropathy.

Diagnosis

Screening

It is estimated that 99% of lead-poisoned children are identified by screening procedures rather than through clinical recognition of lead-related symptoms. Until 1997 universal screening by blood lead testing of all children at ages 12 mo and 24 mo was the standard in the USA. Given the national decline in the prevalence of lead poisoning, the recommendations have been revised to target blood lead testing of high-risk populations. High risk is based on an evaluation of the likelihood of lead exposure. Departments of health are responsible for determining the local prevalence of lead poisoning as well as the percentage of housing built before 1950, the period of peak leaded paint use. When this information is available, informed screening guidelines for practitioners can be issued. For instance, in the state of New York, where a large percentage of housing was built pre-1950, the Department of Health mandates that all children be tested for lead poisoning via blood analyses. In the absence of such data the practitioner should continue to test all children at both 12 mo and 24 mo. In areas where the prevalence of lead poisoning and old housing is low, targeted screening may be performed on the basis of a risk assessment. Three questions form the basis of a questionnaire (Table 702-3), and items that are pertinent to the locale or individual may be added. If there is a lead-based industry in the child’s neighborhood, the child is a recent immigrant from a country that still permits use of leaded gasoline, or the child has pica or developmental delay, blood lead testing would be appropriate. All Medicaid-eligible children should be screened. Venous sampling is preferred to capillary sampling because the chances of false-positive and false-negative results are less with the former.

Table 702-3 MINIMUM PERSONAL RISK QUESTIONNAIRE

From Screening young children for lead poisoning: guidance for state and local public health officials, Atlanta, 1997, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Interpretation of Blood Lead Levels

The threshold for lead effects and the level of concern for risk management purposes are not the same. Laboratory issues make the interpretation of values between 0 and 5 µg/dL more difficult. Some labs certified as proficient by the CDC or other testing programs can accurately measure BLLs to 2 µg/dL; others only to 5 µg/dL. A screening value at or above 2 µg/dL is consistent with exposure and requires a second round of testing for a diagnosis and to determine the appropriate intervention. The timing for the “repeat” evaluation depends on the initial value (Table 702-4). If the diagnostic (second) test confirms that the BLL is elevated, then further testing is required by the recommended schedule (Table 702-5). A confirmed venous BLL of 45 µg/dL or higher requires prompt chelation therapy.

| IF SCREENING BLOOD LEAD LEVEL (µg/dL) IS: | CDC: REPEAT DIAGNOSTIC VENOUS BLOOD LEAD TESTING BY: | AAP: REPEAT DIAGNOSTIC VENOUS BLOOD LEAD TESTING BY: |

|---|---|---|

| <10 | Not defined; < 1 year | Not defined |

| 10-19 | 3 mo | 1 mo |

| 20-44 | 1 wk-1 mo (sooner the higher the lead) | 1 wk |

| 45-59 | 48 hr | 48hr |

| 60-69 | 24 hr | 48 hr |

| ≥70 | Immediately | Immediately |

AAP, American Academy of Pediatrics; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Adapted from Screening young children for lead poisoning: guidance for state and local public health officials, Atlanta, 1997, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Environmental Health: Screening for elevated blood lead levels, Pediatrics 101:1072–1078, 1998.

Table 702-5 SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS FOR CHILDREN WITH CONFIRMED (VENOUS) ELEVATED BLOOD LEAD CONCENTRATIONS

| BLOOD LEAD CONCENTRATION (µg/dL) | RECOMMENDATIONS |

|---|---|

| <10 | As levels approach 10 µg/dL use the 10-14 µg/dL recommendations |

| 10-14 | Lead education (sources, route of entry): |

| Dietary counseling (calcium and iron) | |

| Environmental (methods for hazard reduction) | |

| Follow-up blood lead monitoring in 1-3 mo | |

| 15-19 | Lead education: |

| Dietary | |

| Environmental | |

| Follow-up blood lead monitoring in 1-2 mo | |

| Proceed according to actions for 20-24 µg/dL if: | |

| A follow-up blood lead concentration is in this range at least 3 mo after initial venous test or | |

| Blood lead concentration increases | |

| 20-44 | Lead education: |

| Dietary | |

| Environmental | |

| Follow-up blood lead monitoring in 1 wk-1 mo (sooner if value is higher) | |

| Complete history and physical examination | |

| Laboratory studies: | |

| Hemoglobin or hematocrit | |

| Iron status | |

| Environmental investigation | |

| Lead hazard reduction | |

| Neurodevelopmental monitoring | |

| Abdominal radiography (if particulate lead ingestion is suspected) with bowel decontamination if indicated | |

| 45-69 | Lead education: |

| Dietary | |

| Environmental | |

| Follow-up blood lead monitoring | |

| Complete history and physical examination | |

| Laboratory studies: | |

| Hemoglobin or hematocrit | |

| Iron status | |

| Free erythrocyte protoporphyrin (EP) or zinc protoporphyrin (ZPP) | |

| Environmental investigation | |

| Lead hazard reduction | |

| Neurodevelopmental monitoring | |

| Abdominal radiography with bowel decontamination if indicated | |

| Chelation therapy | |

| ≥70 | Hospitalize and commence chelation therapy |

| Proceed according to actions for 45-69 µg/dL | |

| NOT RECOMMENDED AT ANY BLOOD LEAD CONCENTRATION | |

| Searching for gingival lead lines | |

| Evaluation of renal function (except during chelation with CaNa2EDTA [ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid]) | |

| Testing of hair, teeth, or fingernails for lead | |

| Radiographic imaging of long bones | |

| X-ray fluorescence of long bones | |

From American Academy of Pediatrics: Lead exposure in children: prevention, defection, and management, Pediatrics 116:1036–1046, 2005.

Treatment

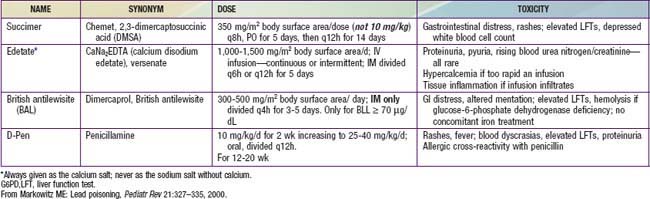

Drug treatment to remove lead is lifesaving for children with lead encephalopathy. In nonencephalopathic children, it prevents symptom progression and further toxicity. Guidelines for chelation are based on the BLL. A child with a venous BLL 45 µg/dL or higher should be treated. Four drugs are available in the USA: 2,3-dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA [succimer]), CaNa2EDTA (versenate), British antilewisite (BAL [dimercaprol]), and penicillamine. DMSA and penicillamine can be given orally, whereas CaNa2EDTA and BAL can be administered only parenterally. The choice of agent is guided by the severity of the lead poisoning, the effectiveness of the drug, and the ease of administration (Table 702-6). Children with BLLs of 44-70 µg/dL may be treated with a single drug, preferably DMSA. Those with BLLs of 70 µg/dL or greater require two-drug treatment: CaNa2EDTA in combination with either DMSA or BAL for those without evidence of encephalopathy, or CaNa2EDTA and BAL for those with encephalopathy. Data on the combined treatment with CaNa2EDTA and DMSA for children with BLLs higher than 100 µg/dL are very limited.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Lead exposure in children: prevention, detection, and management. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1036-1046.

Berkowitz S, Tarrago R. Acute brain herniation from lead toxicity. Pediatrics. 2006;118:2548-2551.

Binns HJ, Campbell C, Brown MJ. Interpreting and managing blood lead levels of less than 10 microg/dL in children and reducing childhood exposure to lead: recommendations of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e1285-e1298.

Canfield RL, Henderson CRJr, Cory-Slechta DA, et al. Intellectual impairment in children with blood lead concentrations below 10 microg per deciliter. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1517-1526.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lead poisoning of a child associated with use of a Cambodian amulet—New York City, 2009. MMWR. 2011;60(3):69-71.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Death of a child after ingestion of a metallic charm—Minnesota, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:340-341.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Deaths associated with hypocalcemia from chelation therapy—Texas, Pennsylvania and Oregon, 2003–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:204-206.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lead exposure from indoor firing ranges among students on shooting teams—Alaska, 2002–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54:577-579.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lead poisoning associated with use of litargirio—Rhode Island, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54:227-229.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lead poisoning associated with Ayurvedic medications—five states, 2000–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:582-586.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance for elevated blood lead levels among children—United States, 1997–2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:1-21.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Childhood lead poisoning associated with lead dust contamination of family vehicles and child safety seats—Maine, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:890-893.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Children with elevated blood lead levels related to home renovation, repair, and painting activities—New York State, 2006–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:55-58.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interpreting and managing blood lead levels <10 µg/dL in children and reducing childhood exposure to lead. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:1-16.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Childhood lead poisoning associated with Tamarind county and folk remedies. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51:684-686.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fatal pediatric lead poisoning—New Hampshire, 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50:457-459.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of acute lead poisoning among children aged <5 years—Zamfara, Nigeria, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:846.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for blood lead screening of medicaid-eligible children aged 1–5 years: an updated approach to targeting a group at high risk. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:1-13.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Notes from the field: outbreak of acute lead poisoning among children aged <5 years—Zamfara, Nigeria. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:846.

Committee on Drugs, American Academy of Pediatrics. Treatment guidelines for lead exposure in children. Pediatrics. 1995;96:155-160.

Committee on Environmental Health, American Academy of Pediatrics. Screening for elevated blood lead levels. Pediatrics. 1998;101:1072-1078.

Dietrich KN, Ware JH, Salganik M, et al. Effect of chelation therapy on the neuropsychological and behavioral development of lead-exposed children after school entry. Pediatrics. 2004;114:19-26.

Florin TA, Brent RL, Weitzman M. The need for vigilance: the persistence of lead poisoning in children. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1767-1768.

Global Lead Network. Alliance to end childhood lead poisoning. www.globalleadnet.org.

Grandjean P. Even low-dose lead exposure is hazardous. Lancet. 2010;376:855-856.

Hu H, Téllez-Rojo MM, Bellinger D, et al. Fetal lead exposure at each stage of pregnancy as a predictor of infant mental development. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:1730-1735.

Jacobs DE, Nevin R. Validation of a 20-year forecast of US childhood lead poisoning: updated prospects for 2010. Environ Res. 2006;102:352-364.

Jones RL, Homa DM, Meyer PA, et al. Trends in blood lead levels and blood lead testing among US children aged 1 to 5 years, 1988–2004. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e376-e385.

Karri SK, Saper RB, Kales SN. Lead encephalopathy due to traditional medicines. Curr Drug Saf. 2008;3:54-59.

Kemper AR, Cohn LM, Fant KE, et al. Follow-up testing among children with elevated screening blood lead levels. JAMA. 2005;293:2232-2237.

Kuehn BM. CDC advises pregnancy lead screening that targets populations at risk. JAMA. 2011;305(4):347.

Lanphear BP. Childhood lead poisoning prevention. JAMA. 2005;293:2274-2276.

Laraque D, Trasande L. Lead poisoning: successes and 21st century challenges. Pediatr Rev. 2005;26:435-443.

Lin CG, Schaider LA, Brabander DJ, et al. Pediatric lead exposure from imported Indian spices and cultural powders. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e828-e835.

Lozoff B, Jimenez E, Wolf AW, et al. Higher infant blood lead levels with longer duration of breastfeeding. J Pediatr. 2009;155:663-667.

Meyer PA, Pivetz T, Dignam TA, et al. Surveillance for elevated blood lead levels among children—United States, 1997–2001. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2003;52:1-21.

Moszynski P. Mass lead poisoning in Nigeria causes “unprecedented” emergency. BMJ. 2010;341:223.

Saper RB, Phillips RS, Sehgal A, et al. Lead, mercury, and arsenic in US- and Indian-manufactured ayurvedic medicines sold via the Internet. JAMA. 2008;300:915-922.

Schnaas L, Rothenberg SJ, Flores MF, et al. Reduced intellectual development in children with prenatal lead exposure. Environ Health Perspect.. 2006;114:791-797.

Selevan SG, Rice DC, Hogan KA, et al. Blood lead concentration and delayed puberty in girls. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1527-1536.

Solon O, Riddell TJ, Quimbo SA, et al. Associations between cognitive function, blood lead concentrations, and nutrition among children in central Philippines. J Pediatr. 2008;152:237-243.

Tellez-Rojo MM, Bellinger DC, Arroyo-Quiroz C, et al. Longitudinal associations between blood lead concentrations lower than 10 microg/dL and neurobehavioral development in environmentally exposed children in Mexico City. Pediatrics. 2006;118:323-330.

Woolf AD, Goldman R, Bellinger DC. Update on the clinical management of childhood lead poisoning. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54:271-294.

Woolf AD, Woolf NT. Childhood lead poisoning in 2 families associated with spices used in food preparation. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e314-e318.

Wright JP, Dietrich KN, Ris MD, et al. Association of prenatal and childhood blood lead concentrations with criminal arrests in early adulthood. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e101-266.