Chapter 35 Lateral and Medial Epicondylitis

Introduction

In continental Europe, the term lateral epicondylitis is often used to describe a painful condition affecting the lateral side of the elbow, more specifically, the origin of the extensors of the wrist. It was first described by Runge in 1873 as ‘Schreibers Krampfes’ (writers cramps), although the name used in the English literature was ‘lawn tennis elbow’, coined by Morris in 1882.1,2

Initially seen as an occupational disease, not necessarily only in tennis players, treatment has focused on changing habits and practices at work or in the case of tennis players properly determine racket grip diameter. Initially overuse, especially repetitive forearm activity and wrist extension, was felt to lead to the development of tendinosis and the formation of granulation tissue in an attempt to repair the damaged extensor tendon origin. More recently, however, literature has focused on the condition being a degenerative tendinopathy of the extensors of the wrist and fingers.3–5

Although lateral epicondylitis is a very common condition, knowledge about its incidence and prevalence is limited. The incidence of lateral epicondylitis in the general population is reported to be 0.6%6 as against 9% in tennis players.7 Prevalence is reported as being between 1% and 3% in the general population8 and 14% in tennis players depending on the age.7 However, one might suspect that with the increased use of computers in day-to-day life, these rates may have risen.

Background/aetiology

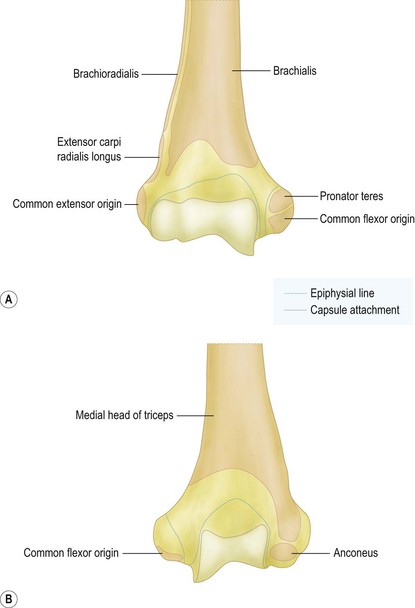

The lateral humeral epicondyle has the origin of the anconeus muscle on its posterior surface, and of both the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) and the extensor digitorum communis (EDC) on its anterior surface. The extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL) and the brachioradialis have a more proximal origin on the anterior aspect of the supracondylar ridge. The common extensor origin consists of the ECRB and the EDC. Degeneration of this tendon usually occurs within the superior deep fibres (Fig. 35.1).

5 – extensor carpi radialis longus

(Redrawn with permission from A Colour Atlas of Human Anatomy, RMH McMinn and RT Hutchings, Wolfe Medical Publications, London.)

There is some dispute about the origin of the pain in lateral epicondylitis. It is, however, likely to be multifactorial. The existence of free nerve endings in the aponeurosis and granulation tissue around the lateral epicondyle was shown by Goldie et al. In addition, biochemical analysis revealed the presence of substance P receptors within the extensor origin and increased levels of the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate in patients with epicondylitis lateralis.9–11 These findings do not directly connect the pain to the lateral epicondylitis, but they do explain the excellent early results of corticosteroid injections into the common extensor tendon origin. In addition, a substantial number of so-called tennis elbow cases have intra-articular abnormalities (11–69%). These include, synovial plicae, synovitis and lateral cartilage degeneration. Indeed the presence of these additional pathologies have led proponents of arthroscopic treatment to recommend this technique.4,12–14

Stage 4: Injury exhibits the features of a stage 2 or 3 injury and is associated with other changes such as fibrosis, soft matrix calcification and hard osseous calcification. The changes that are associated with a stage 4 injury also may be related to the use of cortisone.3

In practice, it is the second stage (angiofibroblastic degeneration) that is most commonly associated with sports-related tendon injuries such as tennis elbow and with overuse injuries in general. Within the tendon, there is a fibroblastic and vascular response (tendinosis) rather than an immune blood cell response (inflammation). Thus, the terms epicondylitis and tendinitis are misnomers. Finally he also postulated that some patients who have tennis elbow may have a genetic predisposition that makes them more susceptible to tendinosis at multiple sites. He termed this condition ‘mesenchymal syndrome’ on the basis of the stem cell line of fibroblasts and the presence of a potentially systemic abnormality of cross-linkage in the collagen produced by the fibroblasts. Patients may have mesenchymal syndrome if they have two or more of the following conditions: bilateral lateral tennis elbow, medial tennis elbow, cubital tunnel syndrome, carpal tunnel syndrome, de Quervain’s tenosynovitis, trigger finger or rotator-cuff tendinosis.3

Traditionally we are taught that symptoms will get better with time: approximately 80% of patients with newly diagnosed lateral epicondylitis report symptomatic improvement at 1 year.15–18 A lesser degree of residual symptoms are, however, not unusual. Finally only 4–11% of patients seek further medical treatment or surgical intervention.4,15,18–20

Poor prognostic factors for obtaining success with non-surgical treatment were identified by Haahr and Andersen and included manual labour, dominant arm involvement, long duration of symptoms with high base line pain levels and poor coping mechanisms.16

Shiri et al described the risk factors for lateral and medial epicondylitis. Smoking or former smoking behaviour was strongly associated with both lateral and medial epicondylitis in their study of 4783 patients in Finland. Also physical load factors, smoking and obesity were strong determinants of epicondylitis.21

Presentation, investigation and treatment options

Presentation

If the degenerative involvement of the ECRB origin is sufficient to compromise the load-bearing capacity of the ECRB tendon, load transfer to the EDC portion of the conjoint tendon may occur. Rarely, even the posteriorly located ECU tendon may also be involved. In these cases involvement of the lateral ulnar collateral ligament (LUCL) may occur with resulting posterolateral instability as a sequel. Posterior interosseous nerve (PIN) involvement may reflect the anatomical proximity of the supinator tendon origin on the deep surface of the ECRB tendon and the secondary changes in the arcade of Frohse, which also originates on this tendon. In cases of radial nerve impingement (radial tunnel syndrome) under the arcade of Frohse, pain is usually concentrated more distally and resisted extension may not be painful, whereas resisted extension of the thumb and the index finger will. In addition, resisted forearm supination may be painful, something which is usually not the case in patients with lateral epicondylitis. However, in 5% of patients, it is said that both conditions can coexist.22 Verhaar and Spaans studied a number of patients with supposedly radial tunnel syndrome. They found that in 14 out of 16 cases there was no evidence of PIN compression on electromyography (EMG). As a consequence they concluded that these data did not support the hypothesis that the signs and symptoms of the majority of cases diagnosed as radial tunnel syndrome are caused by compression of the PIN.23

Investigations

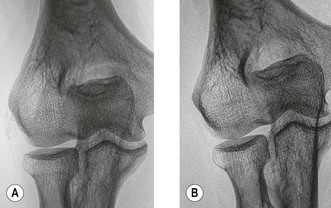

Lateral and medial epicondylitis are essentially a clinical diagnosis. Although additional investigations can be useful to confirm the diagnosis or indeed exclude other conditions. Radiographic examination can reveal small areas of calcification over the lateral epicondyle of the humerus indicating a calcific tendinopathy. Nirschl and Pettrone reported 22–25% of these calcifications in patients with tennis elbow4 (Fig. 35.2). Usually however, radiographs are normal. Tendinopathy of the extensors of the wrist can be visualized by sonography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the latter being more expensive, the former being more operator dependent. Ultrasound investigation visualizes focal hypoechoic areas and intrasubstance tears, as well as peritendinous fluid and thickening of the common extensor tendon.24 Sensitivity is reported to be 64–88% for evaluation of the common extensor origin architecture, but specificity is quite variable (36–100%), depending on the study25,26 (Fig. 35.3).

MRI can also be used for the investigation of suspected intra-articular abnormalities, the intactness of the radial collateral ligament complex as well as the extent of any tear or disease in the common extensor tendon. In 90% of patients, oedema is present within the tendon. It should, however, be noted that oedema has also been seen in 14–54% of asymptomatic patients. Finally the increased T2 signal may persist for weeks after the symptoms have resolved.27–30

Treatment options

Boyer and Hastings in 1999 appealed for better evidence in treating tennis elbow. An examination of the literature can only lead us to believe that most, if not all, common non-operative therapeutic modalities used for the treatment of tennis elbow are unproven at best or costly and time-consuming at worst. Most of the published literature on the non-operative treatment of patients with lateral tennis elbow consists of poorly designed trials. The selection criteria are nebulous, the control group is questionably designed, and the number of patients is often too low to avoid a serious loss of study power. These studies therefore have a high beta error, implying an inability to detect a difference between groups, even if one truly existed. If clinical signs and symptoms persist beyond the limit of acceptability of both patient and surgeon, then an array of surgical options are available. These range from a 10-minute office procedure (percutaneous release of the extensor under local anaesthesia) to an extensive joint denervation, in which all radial nerve branches ramifying to the lateral epicondyle are directly or indirectly divided. How is the surgeon to choose, given the fact that most of the published surgical studies are case series of one type of operation or another, consisting of patients operated on and evaluated by the same authors.31 In 2007, Cowan et al repeated the cry for good clinical research into the treatment of lateral epicondylitis; very little progress being made in the last 10 years!32 As a consequence, while the complete spectrum of treatment will be discussed, it is important to realize that there is little if any hard evidence that one is more effective than another.

In 2006, Bisset et al concluded that physiotherapy combining elbow manipulation and exercise has a benefit over no treatment in the first 6 weeks and to corticosteroid injections after 6 weeks, providing a reasonable alternative to injections in the mid to long term. The significant short-term benefits of corticosteroid injection were paradoxically reversed after 6 weeks, with high recurrence rates, implying that this treatment should be used with caution in the management of tennis elbow.33

Comparing all different treatment options one must consider the natural course of lateral epicondylitis. Hay et al described the effects of corticosteroid injections, non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and a placebo at 4 weeks (92%, 57% and 50% success rate, respectively) and after 12 months (84%, 85% and 82% success rate, respectively) suggesting a benign natural course.34

Supposedly a biomechanically active counter-force brace or ‘tennis elbow strap’ aims to reduce strain at the elbow epicondyle, to limit pain provocation and to protect against further damage. Struijs et al were not able to demonstrate a difference in outcome between patients treated by physiotherapy, a brace or with a combination of both.35 Other treatments with limited scientific support include: pulsed ultrasound to break up scar tissue, promote healing and increase blood flow in the area; extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT); the injection of botulinum toxin; sclerotherapy; acupuncture and trigger point therapy. Based on a systematic review of nine placebo-controlled trials involving 1006 participants, there is ‘platinum’-level evidence that shock wave therapy provides little or no benefit in terms of pain relief or improved function in lateral elbow pain. There is ‘silver’-level evidence based on one trial involving 93 participants that steroid injection may be more effective than ESWT.36

Placzek et al reported on the use and effects of botulinum toxin in lateral epicondylitis, however, although the results were good at 18 weeks after injection, no longer term report exists. Also the side effects of decreased wrist and third finger extension remains an issue of concern.37 Conversely, Keizer et al compared surgery with an injection with botulinum toxin reporting results two years after treatment; 15 patients in the botulinum toxin group (75%) had good to excellent results, whereas 17 patients in the operative group scored good to excellent (85%). When analysed with an overall scoring system, however, no differences were found between the two forms of treatment.38 Finally, Hayton et al in 2005 reported the results of a double-blind randomized effective study in botulinum toxin type A against a normal saline placebo for the treatment of chronic tennis elbow. Three months after injection, there was no significant difference between the two groups with regard to grip strength, pain or quality of life. As a consequence they concluded that there was no evidence for any benefit from botulinum toxin injections in treatment for this condition.39

Edwards and Calandruccio reported that after autologous blood injection therapy 22 patients (79%) in whom non-surgical modalities had failed were relieved completely of pain even during strenuous activity. Mishra and Pavelko described at final follow-up of more than 2 years after injection of buffered platelet-rich plasma a 93% reduction in pain. In both these studies, however, the number of patients was too few to obtain sufficient power.40,41

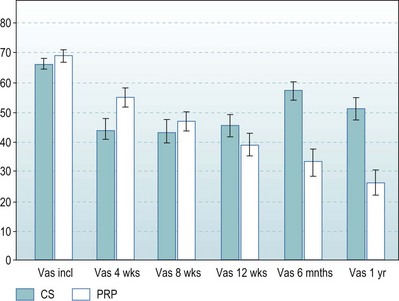

In the Netherlands we performed a prospective randomized, double-blind and multicentred study comparing one injection of corticosteroids with one injection of buffered platelet-rich plasma (PRP) in patient with complaints of lateral epicondylitis for more than 6 months (total of 110 patients, power 0.9). Successful treatment was defined as more than a 25% reduction in visual analogue scale or disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand (DASH) score without a reintervention after 1 year. The results after 1 year showed that 21 of the 55 patients (40%) in the corticosteroid group and 38 of the 51 patients (75%) in the PRP group were defined as successful with the VAS score; this was significantly different (p < 0.001). Twenty-three of the 55 patients (42%) in the corticosteroid group and 36 of the 51 patients (71%) patients in the PRP group were defined as successful with the DASH, which was also significantly different (p < 0.003)42 (Fig. 35.4).

Surgical techniques and rehabilitation

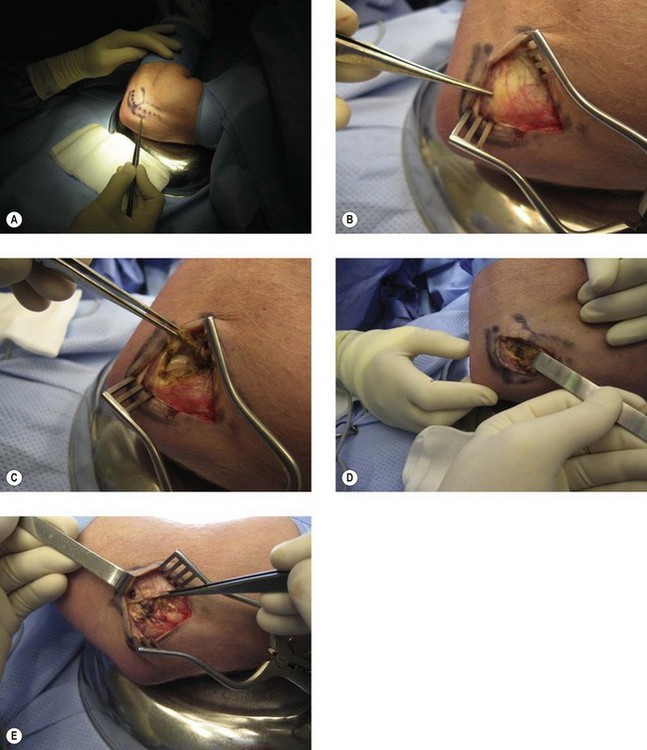

The surgical techniques for treating lateral epicondylitis can be grouped into three main categories: open, percutaneous and arthroscopic (Fig. 35.5). Frequently used open procedures are denervation of the lateral epicondyle as described by Wilhelm and Gieseler or incision of the extensor tendon (especially ECRB) as described by Hohmann.43–45

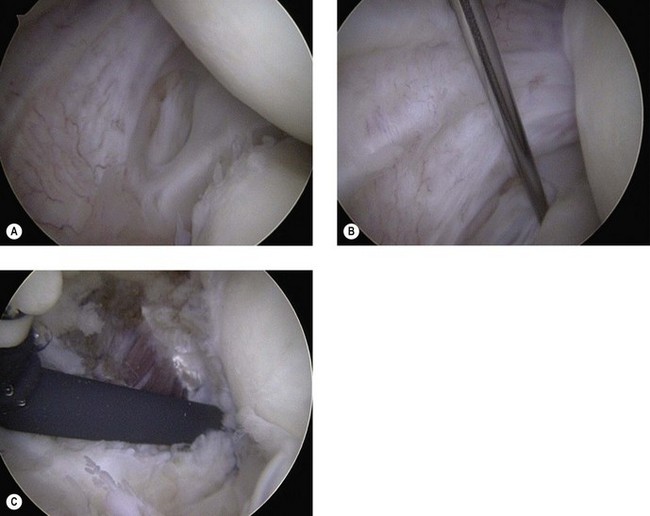

The arthroscopic approach to lateral epicondylitis has many of the same controversies. Some surgeons prefer to debride the lateral capsule alone. Others include any infolded synovial fringe, which may impinge within the radiocapitellar joint, while others focus on the debridement of the common extensor origin. Finally, decortication of the lateral epicondyle is also an issue of debate. Baker et al classified the arthroscopic appearance of the capsule in lateral epicondylitis, reflecting the local intensity of the tendinopathic process. In type 1, a smooth capsule without irregularity is seen. In type 2, a linear or longitudinal tear in the capsule can be visualized, whereas in type 3, a ruptured and retracted capsule with a frayed ECRB is present.12 Finally, other less commonly undertaken procedures include incision of the extensor tendon in combination with a partial resection of the annular ligament, as described by Bosworth, or elongation of the extensor tendons as described by Garden.46,47

Mullett et al described the presence of a synovial fringe/collar-like band of the radiocapitellar capsular complex impinging on the radial head in 30 patients with recalcitrant symptoms of lateral elbow pain.48 Resection of this fringe led to a resolution of symptoms in 28 of 30 patients. Histological examination revealed hyaline degeneration and fibrosis. A cadaveric study identified this same degenerative capsular fold in 15 of 34 cadavers. A classification system was developed: in type 1 the radial head is fully exposed without any capsular impingement or coverage throughout range of motion, whereas in type 2 a partial coverage develops when the elbow is extended. In type 3 there is subluxation of the capsular edge into the radiocapitellar joint and in type 4 the radial head is completely obscured in both flexion and extension.

The set up and technique for performing elbow arthroscopy is described in other chapters of this book, however, it can be performed with the patient in the prone, lateral decubitus or supine position under regional or general anaesthesia. The joint is first injected with saline (usually 30 mL) using the radiocapitellar portal or the soft spot to displace the neurovascular structures anteriorly and away from the portal sites. The proximo-medial portal is used to introduce the arthroscope and the anterior compartment can now be visualized. Using a needle the superolateral portal can now be made under direct vision and the motorised shaver introduced. The degenerative capsule and undersurface of the ECRB can then be released from the lateral epicondyle and the epicondyle decorticated using a motorized burr (Fig. 35.6). The amount of release of the capsule and ECRB should be limited to the line bisecting the radial head as described by Smith et al.49 The anatomical study of Cohen et al proved that this amount of release: ‘from the top of the capitellum to the midline of the radiocapitellar joint’, is in fact the way to perform a safe and complete release of the ECRB.50

Rehabilitation after surgery for medial epicondylitis is similar to that for lateral epicondylitis. In particular, the patient’s arm is immobilized in a splint or sling for 10 days or so. After that, range of motion exercises are begun and after 6 weeks strengthening exercises commence. Again, however, if any repair is undertaken, this programme would be delayed.51

Outcome including literature review

Recently published long-term follow up studies of both arthroscopic and open methods of tennis elbow release have demonstrated remarkably similar outcomes. It appears that either surgical technique is acceptable, as long as the pathological tissue is accurately identified and adequately resected. A 2002 Cochrane Collaboration database review found that no definite conclusions could be drawn regarding the efficacy of operative treatment given the lack of controlled trials. Although there are advantages and disadvantages to each procedure, no technique appears superior by any measure.52

Dunn et al reported the long-term results after the open procedure: results were rated as excellent in 71 elbows, good in 6, fair in 9 and poor in 6 by the Nirschl tennis elbow score. By the criteria of Verhaar et al, the results were excellent in 45 elbows, good in 32, fair in 8 and poor in 7. Eighty-four per cent good to excellent results were achieved using both scoring systems. Ninety-two per cent of the patients reported normal range of motion. The overall improvement rate was 97%. Patient satisfaction averaged 8.9 out of 10. Ninety-three per cent of those available at a minimum of 10-year follow-up reported returning to their sports.53

Baker and Baker reported the long-term results of arthroscopic tennis elbow release. Forty patients (42 elbows) with lateral epicondylitis who had not responded to non-operative management were treated with arthroscopic resection of pathological tissue. Thirty of these patients (30 elbows) were contacted for extended follow-up. At a mean follow-up of 130 months the mean pain score at rest was 0; with activities of daily living, 1.0 and with work or sports, 1.9. The mean functional score was 11.7 out of a possible 12 points. No patient required further surgery or repeat injections. One patient continued to wear a counterforce brace with heavy activities. Twenty-three patients (77%) stated they were ‘much better’, 6 (20%) stated they were ‘better’, and 1 (3%) stated he was the same. Twenty-six patients (87%) were satisfied, and 28 (93%) stated they would have the surgery again if needed.54

Szabo et al performed a retrospective evaluation of three methods of operative treatment. They compared the results in open, arthroscopic and percutaneous cases and found no difference in preoperative parameters such as age, gender, dominance, conservative measures used, cortisone injections or preoperative Andrews–Carson scores. Also, no differences were found at follow-up (minimum of 2 years) in recurrences, complications, failures, VAS scores for pain or postoperative Andrews–Carson scores. It seems therefore that all three methods are an effective way to treat this common elbow problem.55 Another retrospective comparative study between open and arthroscopic procedures was performed by Peart et al. At 6 months no significant difference was seen with nearly 70% good or excellent outcomes. Patients did however return to work earlier after arthroscopic lateral release.51

No prospective comparison is reported for open versus arthroscopic lateral release but Dunkow et al conducted the only prospective, randomized controlled trial on surgery for lateral epicondylitis reported in the literature. They compared 45 patients (47 elbows), comparing a formal open release or a percutaneous tenotomy. Those patients undergoing a percutaneous release returned to work on average 3 weeks earlier and improved significantly more quickly than those undergoing an open procedure. Unfortunately the groups were not compared as to the outcome, so no conclusion can be drawn whether the percutaneous procedure is better than the open procedure or vice versa.56

Lo and Safran published an excellent systematic review in 2007 on the surgical treatment of lateral epicondylitis. They compared studies of arthroscopic, percutaneous and open release of the extensors from the lateral epicondyle, for important factors such as time to return to work, strength and overall function after surgical treatment. For the complete comparison and all included studies the reader is referred to the original study.57 They concluded that comparison of time of return to work was not possible between the three operative methods with the available data. The commonly made claim that arthroscopic or percutaneous surgery leads to a more rapid recovery is therefore not based on evidence, although a trend can be seen towards reducing time off work following arthroscopic procedures.

For medial epicondylitis the reported success rates are equally good for conservative measures, with only 5–10% failing.58 In cases needing surgery, the presence of concurrent ulnar nerve symptoms has a negative effect on outcome, whereas in patients without ulnar nerve symptoms, a success rate of 95% can be expected.

Complications of treatment

Complications arising from the conservative treatment of lateral and medial epicondylitis are essentially the adverse effects of corticosteroids. Apart from having virtually no long-term effect, lipodystrophy at the site of injection should not remain unmentioned. This in fact can lead to bony prominence following the disappearance of the subcutaneous fat surrounding the lateral epicondyle. Following treatment by botulinum toxin, a number of patients develop palsy of the wrist extensors, which can last in the region of 6 weeks to 3 months.37

Excessive debridement of the lateral side of the elbow may result in a compromise of the lateral ligamentous complex, rendering an iatrogenic posterolateral elbow instabile. This is possible with both open and arthroscopic lateral releases. However, by adhering to the guidelines described by Smith et al, this complication can be prevented.49

Obviously with medial epicondyle release, the ulnar nerve is to a degree at risk. More commonly, however, the medial anterior brachial cutaneous nerve can be damaged. This can also result in neuroma formation. Added to this neuroma of the PIN can be a source of persistent postoperative pain and paraesthesia distal to the incision. This can be diagnosed by a local anaesthetic block and treated by excision of the neuroma and intramuscular transposition of the proximal nerve stump. As an adjunct for chronic or recurrent cases, the anconeus flap has been used to provide coverage. Indications for this technique include postoperative symptom recurrence, fistula and infection. It may also be used to close the tissues in cases of wide resection of the extensor origin.59

1 Runge F. Zur Genese und Behandlung de Schreiberskrampfes. Berl Klein Wochenschr. 1873;10:245-248.

2 Morris H. Riders sprain. Lancet. 1882;ii:557.

3 Kraushaar B, Nirschl RP. Tendinosis of the elbow (tennis elbow): clinical features and findings of histological, immunohistochemical, and electron microscopy studies. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1999;81:259.

4 Nirschl RP, Pettrone F. Tennis elbow: the surgical treatment of lateral epicondylitis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1979;61:832.

5 Regan W, Wold LE, Coonrad R, et al. Microscopic histopathology of lateral epicondylitis. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20:746.

6 Lisdonk van der EH, Bosch van der WJHM, Huygen FJA, et al. Ziekten in de huisartspraktijk. Utrecht: Bunge; 1990.

7 Gruchow HW, Pelletier BS. An epidemiologic study of tennis elbow. Am J Sports Med. 1979;7:234-238.

8 Allander E. Prevalence, incidence, and remission rates of some common rheumatic diseases or syndromes. Scan J Rheumatol. 1974;3:145-153.

9 Goldie I. Epicondylitis lateralis humeri (epicondylagia or tennis elbow): a pathogenetical study. Acta Chir Scand Suppl. 1964;57(Suppl.):339.

10 Ljung BO, Alfredson H, Forsgren S. Neurokinin 1-receptors and sensory neuropeptides in tendon insertions at the medial and lateral epicondyles of the humerus: studies on tennis elbow and medial epicodylalgia. J Orthop Res. 2004;22:321-327.

11 Alfredson H, Ljung BO, Thorsen K, et al. In vivo investigation of ECRB tendons with microdialysis technique: no signs of inflammation but high amounts of glutamate in tennis elbow. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71:475-479.

12 Baker CLJr, Murphy KP, Gottlob CA, et al. Arthroscopic classification and treatment of lateral epicondylitis: two-year clinical results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9:475-482.

13 Owens BD, Murphy KP, Kuklo TR. Arthroscopic release for lateral epicondylitis. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:582-587.

14 Ruch DS, Papadonikolakis A, Campolattaro RM. The posterolateral plica: a cause of refractory lateral elbow pain. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15:367-370.

15 Verhaar JA. Tennis elbow: anatomical, epidemiological and therapeutic aspects. Int Orthop. 1994;18:263-267.

16 Haahr JP, Andersen JH. Prognostic factors in lateral epicondylitis: a randomised trial with one-year follow up in 266 new cases treated with minimal occupational intervention or the usual approach in general practice. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003;42:1216-1225.

17 Smidt N, van der Windt DA, Assendelft WJ, et al. Corticosteroid injections, physiotherapy, or a wait-and-see policy for lateral epicondylitis: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:657-662.

18 Binder AJ, Hazleman BL. Lateral humeral epicondylitis: a study of natural history and the effect of conservative therapy. Br J Rheumatol. 1983;22:73-76.

19 Boyd HB, McLeod ACJr. Tennis elbow. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1973;55:1183-1187.

20 Coonrad RW, Hooper WR. Tennis elbow: its course, natural history, conservative and surgical management. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1973;55:1177-1182.

21 Shiri R, Viikari-Juntura E, Varonen H, et al. Prevalence and determinants of lateral and medial epicondylitis: a population study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(11):1065-1074.

22 Werner CO. Lateral elbow pain and posterior nerve entrapment. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1979;174:1-62.

23 Verhaar J, Spaans F. Radial tunnel syndrome. An investigation of compression neuropathy as a possible cause. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1991;73(4):539-544.

24 Connell D, Burke F, Coombes P, et al. Sonographic examination of lateral epicondylitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:777-782.

25 Miller TT, Shapiro MA, Schultz E, et al. Comparison of sonography and MRI for diagnosing epicondylitis. J Clin Ultrasound. 2002;30:193-202.

26 Levin D, Nazarian LN, Miller TT, et al. Lateral epicondylitis of the elbow: US findings. Radiology. 2005;237:230-234.

27 Mackay D, Rangan A, Hide G, et al. The objective diagnosis of early tennis elbow by magnetic resonance imaging. Occup Med (Lond). 2003;53:309-312.

28 Potter HG, Hannafin JA, Morwessel RM, et al. Lateral epicondylitis: correlation of MR imaging, surgical and histopathologic findings. Radiology. 1995;196:43-46.

29 Steinborn M, Heuck A, Jessel C, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of lateral epicondylitis of the elbow with a 0.2 T dedicated system. Eur Radiol. 1999;9:1376-1380.

30 Savnik A, Jensen B, Norregaard J, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of treatment response of lateral epicondylitisof the elbow. Eur Radiol. 2004;14:964-969.

31 Boyer MI, Hastings H2nd. Lateral tennis elbow: ‘Is there any science out there?’. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8(5):481-491.

32 Cowan J, Lozano-Calderón S, Ring D. Quality of prospective controlled randomized trials. Analysis of trials of treatment for lateral epicondylitis as an example. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 2007;89(8):1693-1699.

33 Bisset L, Paungmali A, Vicenzino B, et al. ‘A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials on physical interventions for lateral epicondylalgia’. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(7):411-422.

34 Hay EM, Paterson SM, Lewis M, et al. Pragmatic randomised controlled trial of local corticosteroid injection and naproxen for treatment of lateral epicondylitis of elbow in primary care. BMJ. 1999;319(7215):964-968.

35 Struijs PA, Korthals-de Bos IB, van Tulder MW, et al. Cost effectiveness of brace, physiotherapy, or both for treatment of tennis elbow. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40(7):637-643.

36 Buchbinder R, Green SE, Youd JM, et al. Shock wave therapy for lateral elbow pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(4):CD003524.

37 Placzek R, Drescher W, Deuretzbacher G, et al. Treatment of chronic radial epicondylitis with botulinum toxin A. A double blind, placebo-controlled, randomised multicenter study. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 2007;89:255-260.

38 Keizer SB, Rutten HP, Pilot P, et al. Botulinum toxin injection versus surgical treatment for tennis elbow: a randomized pilot study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;401:125-131.

39 Hayton MJ, Santini AJA, Hughes PJ, et al. Botulinum toxin injection in the treatment of tennis elbow. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 2005;87:503-507. 3

40 Edwards SG, Calandruccio JH. Autologous blood injections for refractory lateral epicondylitis. J Hand Surg (Am). 2003;28(2):272-278.

41 Mishra A, Pavelko T. Treatment of chronic elbow tendinosis with buffered platelet-rich plasma. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(11):1774-1778.

42 Peerbooms JC, Sluimer J, Bruijn DJ, et al. Effect of an autologous platelet concentrate in lateral epicondylitis, a double-blind randomized controlled trial: PRP versus corticosteroid injection with a 1 year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(2):255-262.

43 Wilhelm A, Gieseler H. Die behandlung der epicondylitis humeri radialis durch denervation. Chirurg. 1962;33:118-122.

44 Wilhelm A. Treatment of therapy refractory epicondyliytis lateralis humeri by denervation. On the pathogenesis. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 1999;31:291-302.

45 Hohmann G. Uber den tennisellebogen. Verband Orthop Ges. 1926:349-355.

46 Bosworth DM. The role of the orbicular ligament in tennis elbow. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1955;37:527-533.

47 Garden RS. Tennis elbow. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1961;43:100-106.

48 Mullett H, Sprague M, Brown G, et al. Arthroscopic treatment of lateral epicondylitis. Clinical and cadaveric studies. Clin Orthop. 2005;439:123-128.

49 Smith AM, Castle JA, Ruch DS. Arthroscopic resection of the common extensor origin: anatomic considerations. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12:375-379.

50 Cohen MS, Romeo AA, Hennigan SP, et al. Lateral epicondylitis: anatomic relationships of the extensor tendon origins and implications for arthroscopic treatment. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:954-960.

51 Peart RE, Strickler SS, Schweitzer KM. Lateral epicondylitis: a comparative study of open and arthroscopic lateral release. Am J Orthop. 2004;33:565-567.

52 Buchbinder R, Green S, Bell SN, et al. Surgery for lateral elbow pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(1):CD003525.

53 Dunn JH, Kim JJ, Davis L, et al. Ten- to 14-year follow-up of the Nirschl surgical technique for lateral epicondylitis. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(2):261-266.

54 Baker CLJr, Baker CL3rd. Long-term follow-up of arthroscopic treatment of lateral epicondylitis. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(2):254-260.

55 Szabo SJ, Savoie FH, Field LD, et al. Tendinosis of the extensor carpi radialis brevis: an evaluation of three methods of operative treatment. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15:721-727.

56 Dunkow PD, Jatti M, Muddu BN. A comparison of open and percutaneous techniques in the surgical treatment of tennis elbow. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2004;86:701-704.

57 Lo MY, Safran MR. Surgical treatment of lateral epicondylitis. A systematic review. Clin Orthop. 2007;463:98-106.

58 Almquist EE, Necking L, Bach AW. Epicondylar resection with anconeus muscle transfer in chronic lateral epicondylitis. J Hand Surg (Am). 1998;23:723-731.

59 Luchetti R, Atzei A, Brunelli F, et al. Anconeus muscle transposition for chronic lateral epicondylitis, recurrences, and complications. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2005;9:105-112.