Laparotomy

elective and emergency

INTRODUCTION

Laparotomy (from the Greek laparos = soft, referring to the abdomen) is a skill every surgeon caring for general surgical patients should possess and master to a level which makes him or her confident to perform whenever called upon. The approach to a patient with abdominal pathology has undergone significant changes due to advances in both diagnostic techniques and treatment options. Rapid progress in endoscopic and imaging techniques has led to better preoperative assessment of the abdomen, thereby enabling surgeons to make a more confident decision on the necessity and timing of laparotomy. Minimal access surgery (laparoscopy) has added to the repertoire, aiding both in diagnosis of the acute abdomen1 and in therapeutic procedures. As a result of these changes diagnostic laparotomy is now a rarity. Better understanding of many disease processes, such as peptic ulcer and pancreatitis, and improvements in their pharmacotherapy have led to a significant decrease in patients undergoing laparotomy for these conditions.

Surgical approaches to the abdomen are undergoing continuous change and procedures such as single incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS)2 and natural orifice endoscopic surgery (NOTES),3 whilst still in their infancy, are gaining popularity.

OPENING THE ABDOMEN

Preparation

1. Ideally, see the patient in the ward before their arrival in the operating theatre. Explain the procedure along with the options available and associated risks. Clearly explain any possibility of additional procedures to ensure informed consent. Review the case notes and arrange to display relevant imaging in the operating room.

2. The WHO surgical safety checklist4 is now universally employed in the UK and in many other countries. Follow it meticulously in every case to prevent mishaps arising from human error.

3. Give prophylactic antibiotics at this stage (if not already started), according to hospital guidelines.5

4. Palpate the patient’s abdomen after induction of general anaesthesia. Previously impalpable or indistinct masses may be more evident, such as an appendix mass or empyema of the gall bladder, or less evident, for example an incisional hernia that has spontaneously reduced following muscle relaxation.

5. Consider the patient’s position on the operating table before commencing the procedure. If a lateral tilt is required, secure the patient adequately. Employ a Lloyd-Davies position for all procedures likely to involve the pelvic organs or left colon, to allow access to the rectum.

6. Prepare the skin with an antiseptic solution such as 10% povidone-iodine, 1:5000 chlorhexidine or 1% cetrimide, provided there is no known allergy to any of these agents, using a swab on a sponge holder.5 For a laparotomy, prepare the skin from the nipples to the mid thigh. Alcohol-based antiseptics give superior bactericidal results, but remove any excess (which often pools around the flanks) if diathermy is to be used on the skin or subcutaneous tissues to prevent burns.

7. Drape the patient with sterile drapes, adequately exposing the area of interest. An adhesive plastic drape, such as Opsite™ or Steridrape™ may be used on the exposed skin after the drapes are placed. Make the skin incision through this adhesive drape.

Incisions

1. Principles influencing the choice of incision are adequate exposure, minimal damage to deeper structures, ability to extend the incision if required, sound closure and, as far as possible, a cosmetically acceptable scar. Placement of stomas and the need to access the abdomen quickly may also dictate the choice of incision: thus for abdominal trauma and major haemorrhage always use a midline incision.

2. Placement of the incision depends on the planned procedure: a roof top incision is ideal for surgery on the liver, a left subcostal incision for an elective splenectomy and McBurney’s incision for appendicectomy. Cosmesis is important, but not at the cost of adequate, safe exposure of the relevant structures. Consider achieving a sound repair at the end of the procedure at this stage. There is no conclusive evidence that transverse incisions heal better than vertical incisions but reports support a non-statistical advantage for the former.6

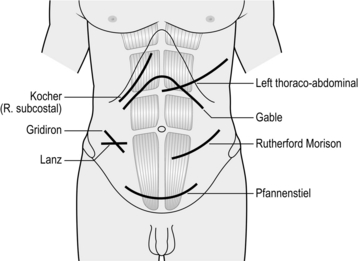

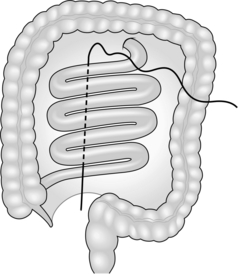

3. Midline laparotomy (Fig. 4.1) is the default incision for most procedures on the abdomen: the extent will vary according to the exposure required. The incision traverses a relatively avascular field (the linea alba). As the peritoneum is exposed, the falciform ligament comes into view in the upper abdomen. This can be ligated and divided or avoided by deepening the incision to one or other side of the ligament. Curve the incision around the umbilical cicatrix to avoid dividing it. Close the midline incision by a single layer mass closure technique using No.1 nylon, polypropylene or PDS. In the lower one-third of the abdomen the posterior rectus sheath is deficient: ensure adequate bites of tissue when closing this part of the incision.

Fig. 4.1 Vertical laparotomy incisions.

4. Paramedian incision (Fig. 4.1). This gives comparable exposure to the midline incision but is time-consuming to create and close, gives an inferior cosmetic result and carries a greater risk of postoperative dehiscence, therefore use a midline incision wherever possible. Make the skin incision 2–3 cms lateral to the midline and incise the anterior rectus sheath along the skin incision. Retract the rectus muscle laterally and incise the posterior rectus sheath and peritoneum in the midline. Close the abdomen in layers: close the peritoneum and the posterior rectus sheath either with Vicryl, PDS, polypropylene or nylon. Allow the rectus muscle to fall back in place and close the anterior rectus sheath. Perform skin closure as usual.

5. Oblique subcostal incisions (Fig. 4.2) are used to access the upper abdomen, for example the liver and gall bladder on the right (Kocher’s incision, after the Nobel prize winner Theodore Kocher, 1841–1917) and the spleen on the left. They may be extended across the midline as a roof top incision if required, for example, in surgery of the liver and pancreas. Make the incision over the area of interest, about two finger breadths below the subcostal margin and towards the xiphisternum. Deepen the incision to expose the external oblique and the anterior rectus sheath. Divide these layers and the rectus muscle and incise the internal oblique muscles with diathermy. It is helpful to insert a long artery forceps such as Robert’s or Kelly’s under the muscle belly to facilitate this. Divide the posterior rectus sheath and transversus abdominis aponeurosis to expose the pre-peritoneal fat and open the peritoneum in line with the incision. Take care to spare the ninth costal nerve, which is visible at this stage. A midline superior extension through the linea alba to form a ‘Mercedes Benz’ incision provides further access if required.

6. The Rutherford Morrison (1853–1939) incision (Fig 4.2) starts about 2 cm above the anterior superior iliac spine and extends obliquely down and medially through the skin, subcutaneous tissues and external oblique along its fibres, cutting the underlying internal oblique and transversus abdominis and the peritoneum along the line of the skin incision. Use an extra-peritoneal approach to place a transplanted kidney in the iliac fossa or to expose the iliac artery during vascular operations. Use a shorter incision, centred over McBurney’s point and splitting the external oblique, internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles along the direction of the fibres (the grid iron incision) in conventional appendicectomy. This incision can be extended laterally and medially if required to convert into a Rutherford Morrison incision.

7. Transverse incisions (Fig. 4.2) provide the best cosmetic scars. They can be used above or below the umbilicus depending on requirements. Ramstedt’s pyloromyotomy and transverse colostomy are performed via incisions above the umbilicus. Lanz incision (Otto Lanz, 1865–1935) is used for appendicectomy and the Pfannenstiel incision (Hermann Johannes Pfannenstiel, 1862–1909) is used for operations on the uterus, urinary bladder and the prostate. The Pfannenstiel incision is a slightly curved horizontal incision about 2–3 cm above the pubic symphysis. Incise the anterior rectus sheath along the skin incision and retract the rectus and the pyramidalis muscles laterally. Incise the peritoneum vertically. Close the peritoneum in the midline using polyglycolic acid sutures and close the rectus sheath with polypropylene, PDS or nylon. The Lanz incision starts 2 cm below and medial to the right anterior superior iliac spine and extends medially for 5–7 cm. The rest of the exposure is similar to the grid iron incision.7

8. Thoraco-abdominal incisions usually follow the line of a rib and extend obliquely into the upper abdomen, dividing the cartilaginous cage protecting the upper abdominal viscera. Alternatively, you may convert a vertical upper abdominal incision into a thoraco-abdominal approach by extending it in the line of a rib across the costal margin. Radial incision of the diaphragm towards the oesophageal hiatus (left) or vena cava (right) converts the abdomen and thorax into one cavity and provides unparalleled access for oesophago-gastrectomy and right hepatic lobectomy. Thoraco-laparotomy may also be indicated for removal of a massive tumour of the kidney, adrenal or spleen.

9. Posterolateral incisions for approach to the kidney, adrenal and upper ureter are described in the relevant chapters.

Making the incision

1. Make the incision with the belly of a no. 20/22 scalpel, holding the knife as you would a table knife and using controlled movements. Once you have cut the skin pass the knife back to the scrub nurse in a kidney dish.

2. Alternatively, use a cutting diathermy spatula. Despite early concerns that the use of diathermy to incise skin and subcutaneous tissue might affect wound healing, it provides superior haemostasis and does not appear to adversely influence wound infection or cosmesis.

3. Deepen the incision using either a scalpel or cutting diathermy spatula. Control any ensuing bleeding from subcutaneous or intramuscular vessels with forceps and diathermy or suture. Use a unipolar or bipolar diathermy forceps, taking care not to burn the adjacent skin. Ligate vessels larger than 2 mm with an absorbable suture.

4. Apply wound towels to the wound edges and clip the tails of these towels with a Dunhill clip so that they are not lost. Change these towels if they become contaminated with infected abdominal contents.

5. Cut, split or retract the muscles of the abdominal wall as required and dictated by the incision that you use. Pick up the peritoneum with Dunhill or Fraser-Kelly artery forceps and tent it up to ensure no bowel is caught. Incise the tented peritoneum to enter the abdominal cavity. In patients with intestinal obstruction, bowel may lie close to the peritoneal incision or, in case of a previous laparotomy, may be adherent to it. Take the utmost care to avoid making an enterotomy which, even if noticed and repaired, may result in subsequent complications.

RE-OPENING THE ABDOMEN

Access through the old incision

1. If the old scar is acceptable make your incision through this without any attempt to excise it. If the scar is ugly or stretched, excise it by making an incision on either side of the scar.

2. For a paramedian scar the dissection is deepened in the line of the skin incision without any attempt to dissect the rectus sheath.

3. Open the peritoneum with great care as adhesions are common and bowel is often adherent to the old scar. It is wise to approach a virgin area first (hence a longer incision than before), then proceed towards the scarred area. Another alternative is to open the peritoneum to one side of the previous scarring and then dissect the scarred area under direct vision. Time spent here is amply justified.

4. Plan a secure closure at the time of the incision, as in a first-time laparotomy. Make sure that adequate abdominal wall and peritoneum remain and are free of adherent viscera.

ABDOMINAL ADHESIONS

1. Adhesions occur in 90–95% of patients undergoing an invasive procedure on the abdomen, irrespective of the operative approach.8,9 They are a cause of much morbidity: 35% of patients with a prior laparotomy will be re-admitted to hospital an average of two times with adhesion-related complications.10 In 1992, a UK survey reported 12 000 to 14 400 cases of adhesive small-bowel obstruction annually; in the USA in 1988, 950 000 days of inpatient care were required for adhesiolysis at a cost of 1.18 billion dollars.11

2. Intra-abdominal trauma or invasion of the peritoneal cavity, infection, bleeding and foreign material (glove powder, fibre from surgical swabs, suture materials, etc.) and intra-peritoneal chemotherapeutic agents are all thought to be responsible for increased formation of adhesions.

3. The most frequent sites are omentum (68%), small-bowel (67%), abdominal wall (45%) and colon (41%).

Prevention of adhesions

1. Meticulous haemostasis, prevention of intra-peritoneal spillage of intestinal contents, minimal handling of bowel, use of powder-free gloves, glove cleansing using a 10% solution of povidone-iodine in a non-toxic detergent base and not closing the peritoneum have all been advocated to prevent adhesion formation.

2. Seprafilm™ (hyaluronate-carboxymethyl cellulose membrane, Genzyme) has been reported to reduce the incidence of adhesions and the number of patients requiring surgery for small-bowel obstruction. However, the incidence of intra-abdominal abscesses and anastomotic leaks was higher in the Seprafilm group compared to controls. Adept™ (icodextrin 4% solution) has been shown to be safe and effective in reducing adhesions during laparoscopy. Interceed™ (oxidized regenerated cellulose, Johnson & Johnson) is another anti-adhesion barrier that has gained popularity among gynaecological surgeons. None, however, have found widespread acceptance, due in part to their cost. A cheaper alternative is liberal irrigation with Ringer lactate solution, which has been reported to decrease adhesions in experimental animal models.

Division of adhesions

1. It is futile to divide every single adhesion as, once divided, they are likely to form again, so divide adhesions only if they are causing a problem. Patients with recurrent adhesive small-bowel obstruction benefit from adhesiolysis and restoration of the bowel anatomy. However, it may be safer to leave the adhesions alone when they are dense but still allow intestinal contents to pass freely.

2. If in the process of releasing the adhesions the bowel is injured, perform a meticulous repair. Minimize contamination of the abdominal cavity by liberal suctioning and lavage.

EXPLORATORY LAPAROTOMY

1. Exploration of the abdomen was used extensively and routinely in the past. Each time an abdomen was opened, the surgeon meticulously and methodically examined every organ to ascertain the cause of the patient’s symptoms. Improvements in diagnostic and imaging methods (in particular endoscopy and computed tomography) have made this unnecessary in most cases. However, exploration is still important in emergencies affecting the abdomen where a clear diagnosis may not be available due to the emergent nature and need to operate without thorough investigation. Knowledge of exploratory laparotomy is, therefore, still important, particularly for surgeons in training.

2. The advent of intra-operative ultrasound, endoscopic ultrasound and in some centres even on-table CT scan and angiography are welcome additions to the surgeon’s armamentarium and may improve the assessment of deeper organs and intraluminal pathology. However, these modalities are not widely accessible and even if the technology is available, the expertise may not be.

3. Despite advances in investigative technology, exploration of the abdomen is still occasionally carried out as an elective ‘final’ diagnostic procedure in patients with inexplicable, distressing or sinister symptoms. However, such instances are becoming increasingly rare: one such example is small-bowel tumours, which were traditionally confirmed at laparotomy but can now be diagnosed on capsule endoscopy. Diagnostic laparoscopy has largely replaced laparotomy in these difficult cases.

4. Symptoms arising from the abdominal wall may confuse the diagnosis. A careful examination performed with the abdomen relaxed and a trial of local anaesthetic may help. Beware of referred pain from the spine and Herpes Zoster infection.

5. In patients with suspected mesenteric ischaemia and possible intra-abdominal sepsis, make an early decision on operative intervention. Diagnostic laparoscopy in the former and a CT scan in the latter may be helpful.

Access

1. The principles governing incisions were addressed at the beginning of this chapter and will be re-addressed in chapters dedicated to the relevant organs. When the diagnosis is in doubt select a midline incision, which is quick, versatile and allows access to the whole abdomen, which affords the luxury of almost unlimited extension from thoracic cavity to pelvis. Other incisions mentioned earlier may be used in specific conditions (Table 4.1).

Table 4.1

Rutherford Morrison incisions to expose abdominal viscera

| Midline | Upper | Hiatus, oesophagus, stomach, duodenum, spleen, liver, pancreas, biliary tract |

| Central | Small-bowel, colon | |

| Lower | Sigmoid, rectum, ovary/tube/uterus, bladder and prostate (extraperitoneal) | |

| Throughout | Aorta | |

| Paramedian (incl. rectus split) | Upper | Biliary tract (right), spleen (left), etc. |

| Central | Small-bowel, colon | |

| Lower | Pelvic viscera, lower ureter (extraperitoneal) | |

| Oblique | Subcostal | Liver and biliary tract (right), spleen (left) |

| Gable (bilateral subcostal) | Pancreas, liver, adrenals | |

| Gridiron | Caecum–appendix (right) | |

| Rutherford Morison | Caecum–appendix (right), sigmoid (left), ureter and external iliac vessels (extraperitoneal) | |

| Posterolateral | Kidney and adrenal (extraperitoneal) | |

| Transverse | Right upper quadrant | Gallbladder, infant pylorus, colostomy |

| Mid-abdominal | Small-bowel, colon, kidney, lumbar sympathetic chain, vena cava (right) | |

| Lanz | Caecum–appendix (right) | |

| Pfannenstiel | Ovary/tube/uterus, prostate (extraperitoneal) | |

| Thoraco-abdominal | Right | Liver and portal vein |

| Left | Gastro-oesophageal junction, enormous spleen |

2. In patients with a previous laparotomy scar, favour the same scar to enter the abdomen, but not at the cost of urgency, exposure or safe closure. Try to avoid an area where a stoma will need to be sited.

3. When the findings on entering the abdomen are different from those suspected preoperatively, the incision may have to be extended or even closed and another incision made. For example, if a duodenal perforation is discovered at appendicectomy, the Lanz incision may have to be closed and a midline incision performed to facilitate appropriate surgery and adequate lavage of the abdomen.

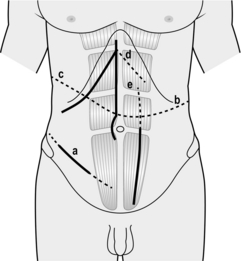

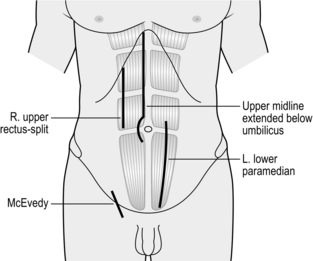

4. Figure 4.3 displays the different techniques to extend incisions in order to deal with unexpected findings or intra-operative difficulties.

5. A wide range of retractors is available. The Goligher, Bookwalter and the Omni-tract retractors greatly facilitate access during a difficult laparotomy and should be kept available. Make sure they can be fixed to the operating table. Proper and liberal use of retractors frees an assistant to be used in other crucial steps.

6. Adjust the patient’s position when required to improve exposure to an organ or area. Tilt the patient away from the area of interest so that bowel falls away, giving a better exposure. This is particularly important in laparoscopic surgery where a tilt of about 20 degrees can make a great difference.

Assess

1. Have the theatre nurse clear all unnecessary instruments from the operative field. Transfer sharp instruments in a kidney dish and not directly, to avoid injuries.

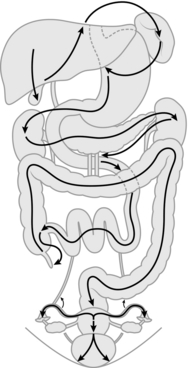

2. Carry out a systematic examination of the abdomen and its contents by feel and visually after ensuring that lighting is optimal. It is recommended that a set sequence is followed in examining the abdominal viscera so that no structure is missed (Fig. 4.4):

Right lobe of liver, gallbladder, left lobe of liver, spleen

Right lobe of liver, gallbladder, left lobe of liver, spleen

Diaphragmatic hiatus, abdominal oesophagus and stomach: cardia, body, lesser curve, antrum, pylorus and then duodenal bulb

Diaphragmatic hiatus, abdominal oesophagus and stomach: cardia, body, lesser curve, antrum, pylorus and then duodenal bulb

Bile ducts, right kidney, duodenal loop, head of pancreas; the transverse colon is drawn out of the wound towards the patient’s head

Bile ducts, right kidney, duodenal loop, head of pancreas; the transverse colon is drawn out of the wound towards the patient’s head

Body and tail of pancreas, left kidney

Body and tail of pancreas, left kidney

Root of mesentery, superior mesenteric and middle colic vessels, aorta, inferior mesenteric artery and vein, small-bowel and mesentery from ligament of Treitz to ileocaecal valve

Root of mesentery, superior mesenteric and middle colic vessels, aorta, inferior mesenteric artery and vein, small-bowel and mesentery from ligament of Treitz to ileocaecal valve

Appendix, caecum, colon, rectum

Appendix, caecum, colon, rectum

Pelvic peritoneum, uterus, tubes and ovaries in the female, bladder

Pelvic peritoneum, uterus, tubes and ovaries in the female, bladder

Hernial orifices and main iliac vessels on each side: the ureters can sometimes be seen in thin patients, or if they are dilated.

Hernial orifices and main iliac vessels on each side: the ureters can sometimes be seen in thin patients, or if they are dilated.

3. Record the findings of this exploration in detail at the end of the operation. You may be able to dictate the findings to an observer for direct entry into the operation notes.

4. In the presence of a tumour it is usual to adopt a no touch or minimal touch technique, although there is no firm evidence that this improves survival.12

5. In emergency laparotomy immediate action may be required, for example to stop bleeding or close a perforation. Thereafter, perform a methodical examination of the other viscera unless the patient’s general condition precludes it. Note the nature and amount of any free fluid, collecting some for chemical, cytological and microbiological examination.

Action

1. Make a decision on any definitive procedure: consider the preoperative diagnosis, operative findings and the patient’s condition. In elderly or sick patients control of the emergency condition takes precedence over the complete eradication of disease. Inform the anaesthetist as soon as you decide a course of action.

2. Incidental findings such as gallstones, diverticula, fibroids or ovarian cysts do not automatically call for action unless they pose an immediate threat to health or offer a better explanation for the patient’s symptoms than the original diagnosis. Similarly, during a laparotomy for another condition, do not perform an appendicectomy without an indication. The patient’s prior consent is unlikely to have been obtained, so any adverse outcome may be more difficult to defend. By contrast, ordinarily remove an unsuspected neoplasm, if necessary through a separate incision, provided the patient’s condition allows. Whatever course you adopt, meticulously record the findings in the operation notes.

3. The contents of the distal small-bowel and the entire large-bowel are unsterile. Visceral contents that are normally sterile such as bile, urine and gastric juice may also become infected as a result of inflammation and obstruction. Before opening the bowel or other potentially contaminated viscera, isolate the area from contact with the wound and other organs by using moist abdominal swabs. Apply non-crushing clamps to occlude the lumen and ensure that an efficient suction apparatus is available to remove any contents that spill. Following closure of the viscus discard all instruments and swabs used on opened bowel and change gloves.

4. The risk of infection depends on the degree of contamination. Healthy tissues can normally cope with a small number of organisms but are overwhelmed by heavy contamination or re-infection. Logically, reducing bacterial contamination reduces infection.

5. Patients with impaired local host defences, such as those on immuno-suppressants, steroids and diabetic patients, are susceptible to a wide range of organisms including fungi, particularly if they have previously had antibiotics. When there is gross infection (peritonitis) or spillage into the peritoneal cavity, liberally irrigate with warm saline or diluted povidone-iodine to reduce the bacterial load.

6. With the increased use of intestinal staplers, bowel clamps are infrequently used in some centres. It is, however, useful to know the types of bowel clamp and when they should be used. Intestinal clamps are of two types: crushing and non-crushing:

Crushing clamps are applied to seal the bowel when it is cut. Payr’s powerful double-action clamps are most frequently used, but Lang Stevenson devised a similar clamp with narrow blades. Cope’s triple clamps allow the middle clamp to be removed, so that the bowel can be divided through the crushed area, leaving its ends sealed. These clamps are useful in partial gastrectomy.

Crushing clamps are applied to seal the bowel when it is cut. Payr’s powerful double-action clamps are most frequently used, but Lang Stevenson devised a similar clamp with narrow blades. Cope’s triple clamps allow the middle clamp to be removed, so that the bowel can be divided through the crushed area, leaving its ends sealed. These clamps are useful in partial gastrectomy.

Non-crushing clamps have longitudinal ridges and control the leakage of bowel contents without causing irreversible damage to the gut. Lane’s twin clamps, which can be locked together, allow two segments of intestine to be occluded and held in apposition for anastomosis. Pringle’s clamps hold cut ends of bowel securely, and the lightly crushed segment is so narrow that it can safely be incorporated in the anastomosis.

Non-crushing clamps have longitudinal ridges and control the leakage of bowel contents without causing irreversible damage to the gut. Lane’s twin clamps, which can be locked together, allow two segments of intestine to be occluded and held in apposition for anastomosis. Pringle’s clamps hold cut ends of bowel securely, and the lightly crushed segment is so narrow that it can safely be incorporated in the anastomosis.

7. We are all familiar with stories of instruments and swabs left inside the abdomen and this represents one of the surgeon’s worst nightmares. There is no single routine that entirely guards against this mishap. Use the minimum number of instruments and the largest swabs, which should remain attached to large clips lying outside the abdominal wound. Avoid using small swabs deeply within the abdomen. If possible, use long-handled instruments on tissues and structures when prolonged use is anticipated. Although the primary responsibility of leaving a swab or an instrument in the abdomen rests with you as the operating surgeon, encourage the entire team to take an active role in preventing it. The scrub nurse counts the instruments and swabs before the procedure and before closure of the operative wound. He or she also counts any extra instruments, needles or swabs used during the procedure. If the scrub nurse reports a missing swab or instrument while closing the abdomen, carry out a thorough search of the abdomen and vicinity. If all else fails, perform an abdominal X-ray before waking the patient from the anaesthetic.

PERITONEAL LAVAGE

1. The peritoneal cavity has a remarkable ability to combat sepsis. Nonetheless, spillage of contaminated contents, such as faeces or infected bile, may lead to early septicaemia and late abdominal abscess.

2. Where local peritonitis is marked, carry out peritoneal lavage with warm saline, sucking out the fluid and inserting a drain. The theoretical risk of disseminating the infection throughout the peritoneal cavity does not appear to hold true in practice.

3. In generalized peritonitis, wash out the peritoneal cavity with warm saline (1–2 L or more) at the end of the operation. In very severe cases (e.g. pancreatic necrosis, faecal peritonitis), be prepared to insert one or two drainage tubes for postoperative lavage. Place one drainage tube in the abscess cavity and one in the pelvis: soft, wide-bore silicone tubes or sump drains are appropriate. Irrigate with warmed (37 °C) peritoneal dialysis fluid (Dialaflex 6 L) with added potassium at a rate of 50–200 ml/hour, depending on the extent of sepsis. A water-tight closure of the abdominal wound is essential, so initially perfuse a small amount of dialysate (50 mL/hour) overnight until the peritoneum seals any defects. Postoperative lavage is well tolerated and does not seem to interfere with intestinal motility. Continue the treatment until there is clinical improvement and the effluent becomes clear.

CLOSING THE ABDOMEN

1. The scrub nurse will check counts of swabs, instruments and needles to confirm that they are correct.

2. To drain or not to drain? Leaving a drain in the abdomen following a major laparotomy has been frequently questioned. There is no evidence to support their use in every case and in elective abdominal surgery most studies have found no benefit from drainage.13 A selective use policy is more appropriate, and indications for draining the peritoneal cavity may include the following:

Operations on the bile ducts or pancreas where there is potential leakage of bile or pancreatic juice

Operations on the bile ducts or pancreas where there is potential leakage of bile or pancreatic juice

Where there is a localized abscess

Where there is a localized abscess

After suture of a perforated viscus where the tissues are friable, or when a controlled fistula is planned

After suture of a perforated viscus where the tissues are friable, or when a controlled fistula is planned

When there is a large raw area from which oozing can occur. Meticulous haemostasis is preferable.

When there is a large raw area from which oozing can occur. Meticulous haemostasis is preferable.

3. Carefully return abdominal viscera to the abdominal cavity, taking care there are no twists in the bowel.

4. There are several different techniques for abdominal closure with no consensus on which is best.14 The choice depends upon the type of incision, the extent of the operation, the patient’s general condition and your preference. It is a common error among surgical trainees to sew up the abdomen too tightly. Wounds swell during the first 3–4 postoperative days, oedema makes the sutures even tighter and there is a risk of tissue necrosis and subsequent dehiscence:

Mass closure technique is currently used by most surgeons with evidence that this technique is associated with the lowest incidence of wound dehiscence.15 It is usually used following midline laparotomy, but can used with subcostal or transverse abdominal incisions.

Mass closure technique is currently used by most surgeons with evidence that this technique is associated with the lowest incidence of wound dehiscence.15 It is usually used following midline laparotomy, but can used with subcostal or transverse abdominal incisions.

Close the abdomen with No.1 nylon, polypropylene or polydioxanone (PDS). There is evidence that PDS causes fewer stitch sinuses than non-absorbable sutures.

Close the abdomen with No.1 nylon, polypropylene or polydioxanone (PDS). There is evidence that PDS causes fewer stitch sinuses than non-absorbable sutures.

A continuous stitch is more secure than interrupted stitches. Place the sutures 1 cm away from the wound edge and at 1-cm intervals.

A continuous stitch is more secure than interrupted stitches. Place the sutures 1 cm away from the wound edge and at 1-cm intervals.

The length of the suture used should be four times the length of the wound.16

The length of the suture used should be four times the length of the wound.16

There is disagreement about the use of tension sutures. In the presence of risk factors for poor healing such as a distended or obese abdomen; if the wound is infected or likely to become so; if the patient is malnourished, jaundiced or suffering from advanced cancer, consider using these sutures. However, they cause ischaemia and necrosis of the tissues, resulting in delayed wound healing and severe pain, and may contribute to respiratory compromise and abdominal compartment syndrome. Most surgeons reserve them for the repair of complete abdominal dehiscence (‘burst abdomen’).

There is disagreement about the use of tension sutures. In the presence of risk factors for poor healing such as a distended or obese abdomen; if the wound is infected or likely to become so; if the patient is malnourished, jaundiced or suffering from advanced cancer, consider using these sutures. However, they cause ischaemia and necrosis of the tissues, resulting in delayed wound healing and severe pain, and may contribute to respiratory compromise and abdominal compartment syndrome. Most surgeons reserve them for the repair of complete abdominal dehiscence (‘burst abdomen’).

Subcutaneous sutures are generally not necessary. There is no evidence that suturing this layer affords any benefit.17

Subcutaneous sutures are generally not necessary. There is no evidence that suturing this layer affords any benefit.17

Mass closure

1. As a rule, use this technique for closing a midline laparotomy wound or a laparotomy through a previous scar. It can also be used in oblique or transverse incisions.

2. The peritoneum need not be sutured. Peritoneal closure is thought to predispose to adhesion formation.

3. Pick up the linea alba with a Kocher’s or Lane’s forceps to clearly define the apex and the lower end. Using a No.1 nylon/polypropelene/PDS suture on a blunt or taper-cutting needle, approximate this layer with a continuous running stitch using a 1:4 wound-to-suture length ratio, ensuring that no intraperitoneal contents are caught in the stitch. When half the length of the wound is approximated, commence suturing from the other end and tie the two sutured segments in the middle with a secure knot. Bury the knot under the fascial layer so that it does not lie subcutaneously and cause discomfort.

4. Secure haemostasis in the subcutaneous fat using diathermy or ligatures as required. This layer is usually not approximated but if it is very thick, 2/0 or 3/0 polyglactin (Vicryl) interrupted sutures may be used to obliterate the potential dead space. An inverted suture, starting and ending in the depth of the wound buries the knot, giving a better result.

5. Approximate the skin with 3/0 or 4/0 undyed polyglactin (Vicryl) or polygecaprone (Monocryl) subcuticular sutures. When the wound is contaminated, use staples or interrupted non-absorbable sutures such as 3/0 nylon or polypropylene. When the wound is dirty, you may leave open the skin and subcutaneous fat, undertaking delayed primary closure 5 days later.

Layered closure

1. The peritoneum is left to heal by mesothelial regeneration, thereby reducing the chances of adhesion formation.

2. In paramedian, oblique and transverse incisions the posterior rectus sheath/tranversus aponeurosis/internal oblique muscles are sutured using polyglactin 910, PDS no.1 or nylon/polypropylene no.1.

3. The muscle layer can safely be left alone without suturing, especially when it is split and not cut.

4. The anterior rectus sheath/external oblique aponeurosis is sutured with a no.1 PDS, nylon or polypropylene continuous suture.

5. Subcutaneous fat and skin are then dealt with as described above.

Tension sutures

1. Use tension sutures in patients who have risk factors predisposing to wound dehiscence (vide supra) and in patients with established full thickness wound dehiscence (‘burst abdomen’).

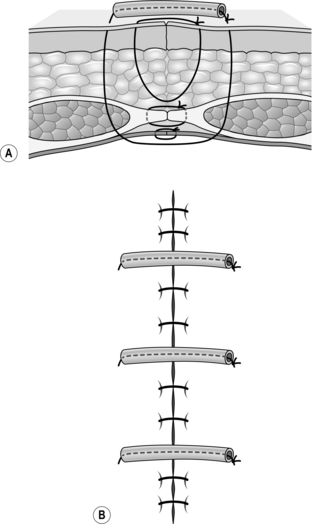

2. Use No.1 or 2 nylon or polypropylene full-thickness interrupted sutures which include all layers of the abdominal wall including the skin. They can be placed as vertical simple or mattress sutures (Fig. 4.5A). Avoid using horizontal mattress sutures as they cause ischaemia of the tissue within the stitch. Thread small 4 to 5-cm segments of plastic or rubber tubing on to the sutures on one side and leave them ready to tie. Perform mass closure of the abdomen as described above and tie the tension sutures sequentially as the mass closure progresses (Fig. 4.5B).

3. Approximate the skin if it is clean or relatively clean, using interrupted 3/0 nylon or polypropylene.

The difficult closure

1. At times closure of the abdomen may be the most difficult part of the operation, even to an experienced surgeon. Inadequate closure can be disastrous, but take the utmost care to make sure there is no injury to the bowel.

2. Relaxation of the abdomen is extremely important throughout a laparotomy and this applies equally during closure of the abdomen. Maintain good communication with the anaesthetist.

3. It is good practice to place the omentum over exposed bowel in the wound when possible.

4. Place an abdominal swab over the bowel and omentum to help prevent them from being caught in the suture during abdominal closure. Remove the swab before inserting the last few sutures.

5. If there is too much tension in the middle of the wound, it is easier to stitch the wound alternately from either end, slowly advancing towards the centre. Use interrupted sutures in this situation as they help to reduce the tensile force on the suture. Unlike a continuous suture, if one stitch subsequently fails the other sutures will hold.

6. If the wound cannot be closed despite these simple steps, you may use a variety of different materials including bio-prostheses to obtain a tension-free closure.18,19

7. In an emergency and when biomaterials are not available, temporary abdominal closure can be achieved using a Bogota bag.20 Empty a large sterile saline plastic bag, open it and suture the edges to the rectus sheath to close the abdomen, or use an Opsite ‘sandwich’ vacuum dressing.21 These are commonly used in the grossly infected abdomen to allow drainage of sepsis prior to a delayed closure.22 Newer (and more costly) alternatives include Strattice (Lifecell Corporation),23 a biocompatible tissue matrix which allows ingrowth of healing tissue, the ABRA system (Canica Design Inc.),24 which uses tensioned silicone elastomers to re-approximate the edges of the fascial defect allowing delayed primary closure in 60% of cases, and the V.A.C. system (KCI Medical Ltd.). The latter uses a permeable membrane and porous foam dressing in combination with a closed, low-pressure suction drainage system which removes exudate from the wound whilst preventing retraction of the wound edges, and has been shown to reduce mortality compared to conventional treatment methods.25 Be aware in patients with a newly fashioned anastomosis that a higher rate of anastomotic leakage has been reported following V.A.C. therapy.

Delayed closure

1. If the abdominal cavity is grossly contaminated, as in faecal peritonitis, some degree of wound sepsis is almost inevitable. One option is to close the superficial tissues lightly around a drain. Another is delayed primary suture, leaving the skin and subcutaneous tissue widely open. In either case give parenteral antibiotics and drain the peritoneal cavity.

2. Suture the musculo-aponeurotic layers of the abdominal wall with a continuous monofilament nylon suture, taking care not to draw the edges together too tightly as considerable swelling can be anticipated. Superficial to this layer, loosely pack the wound with gauze swabs wrung out in saline. Change these packs and inspect it daily. Perform delayed closure when the condition of the wound improves, usually at around 5 days.

3. If peritonitis is particularly severe, for example after a major colonic perforation or infected pancreatic necrosis, some surgeons prefer to leave the abdomen completely open as a ‘laparostomy’, employing a Bogota bag and sometimes a zip fastener, with daily irrigation of the peritoneum. The drawbacks of this approach are lateral retraction of the rectus sheath with fusion of the small-bowel to the wound edges, high metabolic demands (malnutrition and fluid losses) and an increased risk of enteric fistulae.26 If the patient survives, late closure of the large incisional hernia is usually required and is frequently challenging. In our opinion it is advisable to avoid the technique wherever possible.

Abdominal dressings

The UK National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines27 recommend an appropriate dressing depending on the nature of the wound and anticipated discharge. A plastic spray may be used if the wound is not expected to discharge much; use a more absorbent dressing when you expect discharge from the wound (for example after a laparotomy for peritonitis or in a patient with ascites).

ABDOMINAL COMPARTMENT SYNDROME

1. Abdominal compartment syndrome may be primary (intra-abdominal peritonitis, mesenteric ischaemia, obstructed bowel or intra-abdominal bleeding), or secondary to causes outside the abdomen, such as sepsis elsewhere, causing paralytic ileus28 or colonic pseudo-obstruction.

2. The consequences of a raised intra-abdominal pressure are:

Respiratory failure and the need for higher ventilator pressures in mechanically ventilated patients

Respiratory failure and the need for higher ventilator pressures in mechanically ventilated patients

Decreased venous return due to compression of the inferior vena cava

Decreased venous return due to compression of the inferior vena cava

Decreased renal perfusion causing acute renal failure

Decreased renal perfusion causing acute renal failure

Reduced splanchnic (G splanchnon = visceral, intestinal) perfusion causing intestinal ischaemia.

Reduced splanchnic (G splanchnon = visceral, intestinal) perfusion causing intestinal ischaemia.

3. Intra-abdominal pressure is usually measured using a Foley catheter in the bladder primed with 50 ml of fluid. However, there are concerns that measurement of bladder pressure may over-estimate abdominal pressure, and the results should be taken in the context of other parameters such as respiratory pressures and oxygen saturation, renal function and urine output, lactate levels and abdominal distension.

BURST ABDOMEN

This is full thickness dehiscence of a laparotomy wound. The incidence of burst abdomen ranges from 0.6% to 6% and mortality is around 10-40%.29 Predisposing factors for wound dehiscence are anaemia, hypoalbuminaemia, malnutrition, malignancy, jaundice, obesity and diabetes, male gender, elderly patients and emergency laparotomy:30

1. Dehiscence usually declares itself on the 6th to 15th postoperative day31. It may be preceded by low-grade pyrexia and there may be delay in the return of bowel sounds.

2. In 85% of patients impending full thickness dehiscence presents with a salmon pink serous exudate from the wound.

3. Wound disruption may occur without warning following straining or removal of the sutures. The dehiscence may be associated with evisceration of abdominal contents, although sometimes the bowel does not eviscerate, leaving an open abdomen with adherent bowel visible in the depths of the wound.

Management

1. Reassure the patent and provide adequate analgesia and sedation. A burst abdomen, particularly with evisceration of the bowel, is a frightening experience for the patient and relatives. If the wound is relatively clean and if the bowel is eviscerating undertake immediate repair of the wound to prevent bowel injury or strangulation.

2. Fluid resuscitation is important as exposed bowel tends to lose large amounts of fluid rapidly. Administer broad-spectrum antibiotics if not already prescribed.

3. Make an attempt to reduce the exposed bowel back into the abdomen and dress the wound with a non-adhesive dressing. If the bowel cannot be reduced, cover it with an empty sterile 3 L saline bag and make arrangements to transfer the patient urgently to theatre.

4. During closure of the burst abdomen take a swab for microbiology and use liberal amounts of warm saline to wash out the peritoneal cavity. Make no attempt to mobilize densely adherent bowel as there is high risk of bowel injury at this stage. If there is an anastomotic dehiscence, deal with it by exteriorization or re-anastomosis (ideally with a covering stoma). Close the abdomen with interrupted polypropylene or nylon no.1 sutures, supported by deep-tension sutures. Close the skin if the wound is clean, leave it open if the wound is grossly contaminated. If the abdomen cannot be closed and the linea alba is retracted too far laterally, resort to temporary closure using the techniques described above, leaving the wound to heal by secondary intention. Repair the ensuing incisional hernia electively. Various other techniques that are used to achieve closure of a burst abdomen include biosynthetic or synthetic mesh,18 component separation32 or a combination of these techniques.

5. While suturing the abdominal wall, take care not to use excess force as the sutures will tear out of the inflamed tissues.

LAPAROTOMY FOR PERITONITIS

APPRAISE

1. Intra-abdominal sepsis in critically ill patients carries a significant mortality (32% in patients with an APACHE score of more than 10).33 Features of peritonitis develop when the parietal peritoneum is irritated either by an inflamed organ such as appendix, gall bladder, colonic diverticulitis or fallopian tube or by chemical contact with gastric juice, bile, activated pancreatic enzymes, bowel contents or blood. The features may be localized over the inflamed structure or generalized, depending on the patient’s capacity to contain the inflammation with the help of the omentum and surrounding bowel.

2. A patient with generalized peritonitis presents with sudden-onset abdominal pain, worse on movement. On examination the patient is tachycardic, tachypnoeic and pyrexial with generalized tenderness, rigidity and rebound tenderness. If the inflammation is localized, the abdominal signs are also localized to that area. A patient who develops septicaemia may become hypothermic instead of pyrexial.

3. It is good practice to re-examine the patient after an interval. The features of generalized pain may have localized, as in the case of appendicitis or cholecystitis, or a localized pain may have become generalized as in the case of appendicular perforation. In patients with a duodenal perforation, pain that is excruciating may completely wane and re-appear later. This is due to the different phases of peptic ulcer perforation: the initial chemical peritonitis due to gastric acid or bile leaking into the peritoneum leads to a peritoneal reaction and features of peritonitis. This in turn leads to fluid exudation, thus diluting the gastric acid or bile, and the pain wanes. Infection secondary to bacterial contamination results in further pain and the patient again exhibits features of peritonitis.

4. Perform a urine examination and a pregnancy test in women of child-bearing age. Order blood tests including haemoglobin, white cell count, platelet count, renal function, liver function, amylase, pancreatic lipase and a blood gas. Erect chest X-ray or lateral decubitus abdominal X-ray may demonstrate signs of free intra-peritoneal air. If available, order a CT scan of the abdomen, which will usually reveal the cause of the peritonitis and will also differentiate pancreatitis and may avoid an unnecessary laparotomy.

5. Immunocompromised patients (those with AIDS or transplant patients on immunosuppressants) may present with particular diagnostic problems such as toxic megacolon, appendicitis caused by cytomegalovirus (CMV), spontaneous bacterial peritonitis or atypical mycobacterial infection.

6. Exclude medical conditions such as diabetic keto-acidosis, Henoch-Schonlein purpura, porphyria, sickle cell crisis, basal pneumonia and pyelonephritis, which may mimic peritonitis.

7. Critically ill patients who develop an acute abdomen present a diagnostic challenge. An urgent CT scan of the abdomen will usually provide a diagnosis. Acalculous cholecystitis is common in acutely ill patients in the intensive care setting: order an ultrasound scan, which can be performed at the bedside, in septic patients with right upper quadrant signs to confirm the diagnosis.

8. Very occasionally, generalized peritonitis develops in the absence of any overt visceral pathology. Primary peritonitis, commonly due to Streptococcus pneumoniae, can occur spontaneously in children and in patients with ascites, nephrotic syndrome and in patients undergoing continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD).

9. Diagnostic laparoscopy is used increasingly in assessment of the acute abdomen. It can be very helpful in equivocal cases but is unnecessary if there is clear evidence of generalized peritonitis.

Decision

1. It is often valuable for an individual or a small group to sit down and review what has been discovered, what it means and what should be done about it before taking a decision on treating a patient with an acute abdomen. Operative intervention may not always be the correct course.

2. Re-examining the patient after an interval may give new clues to the diagnosis or the diagnosis may become more apparent. If the patient’s condition permits, go back after a few hours and re-examine them, looking for any new signs.

3. A decision to treat a patient conservatively is always provisional and subject to monitoring and repeated examination. If the patient is not responding to the treatment regime consider changing the strategy. Diagnostic imaging may be required or the patient may need an operation.

4. When clinical findings and investigations do not match, trust your clinical findings provided they are based on a thorough and accurate clinical examination.

Prepare

1. Correct any fluid, electrolyte or acid–base imbalance intravenously.

2. Pass a nasogastric tube and aspirate the stomach.

3. As far as possible assess and correct incidental medical conditions, in particular cardiorespiratory disease.

4. Start parenteral broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, such as a third-generation cephalosporin with an aminoglycoside and metronidazole, according to your hospital protocol. A wide spectrum of pathogens may be encountered, particularly in critically ill or immune-suppressed patients, including Candida albicans, Enterococcus sp. and Staphylococcus epidermidis.

Access

1. Examine the abdomen under anaesthetic. It may reveal an unsuspected mass. If there are no localizing signs, use a midline incision centred on the umbilicus. Be prepared to extend it in either direction once the cause is evident.

2. If peritonitis follows a recent operation, re-open the previous incision (vide infra).

Action

1. Make sure that the incision, the assistance, the lighting and the instruments available are adequate for the proposed procedure.

2. Resect an inflamed, perforated appendix or Meckel’s diverticulum. Undertake cholecystectomy for a perforated empyema of the gallbladder; if dissection proves difficult due to dense fibrosis or bleeding, drain the gallbladder using a Foley catheter as a cholecystostomy. Close a perforated peptic ulcer using a Graham’s omental patch.

3. Treat localized injuries to the small-bowel by primary repair, provided soiling is not excessive. Resect gangrenous or ischaemic small-bowel but undertake primary anastomosis only if the proximal and distal margins are healthy and viable.

4. Resect perforated colon, but be very cautious about restoring intestinal continuity without a proximal diverting colostomy. Resection with exteriorization of the bowel ends is an even safer option. Sigmoid diverticulitis with purulent peritonitis can often be treated by lavage and drainage without resection of the diverticular segment, but resect perforated carcinomas if possible.

5. Recognize acute pancreatitis by a bloodstained effusion, discoloration of the retroperitoneum and the presence of whitish patches of fat necrosis. In salpingitis, the uterine tubes are reddened, swollen and oedematous, often discharging pus from the abdominal ostia. Crohn’s disease of the terminal ileum manifests as inflamed, thickened bowel and mesentery, typically with ‘fat wrapping’ of the bowel. In these conditions do not undertake any resection, but close the abdomen and institute appropriate medical therapy.

6. Make sure no dead or devitalised tissue remains and remove any foreign bodies from the peritoneal cavity. Drain abscesses and institute copious lavage with warm normal saline if there is infection or contamination by intestinal contents.

7. Your priority throughout the operative procedure is to identify the cause of the patient’s condition and deal with it, in order to avoid the need for re-operation. In patients in whom a single surgical intervention is performed the mortality rate is 27%, compared with 42% for subjects undergoing multiple laparotomies.33,34 The role of planned re-laparotomy in critically ill patients with abdominal sepsis has been questioned: the use of predictive indices, used to guide decisions on re-laparotomy, has been shown to reduce mortality.35

LAPAROTOMY FOR INTESTINAL OBSTRUCTION

Appraise

1. Patients with intestinal obstruction have a varied presentation ranging from colicky abdominal pain and distension to strangulated bowel with peritonitis. Classically there are four cardinal features—colic, distension, vomiting and constipation—but the prominence of each of these is affected by the site and type of obstruction: for example a high intestinal obstruction presents with profuse vomiting and pain in the absence of abdominal distension.

2. Small-bowel obstruction is most commonly secondary to adhesions resulting from a previous laparotomy. Examination of the hernia orifices (inguinal, femoral, umbilical and incisional) is vital. Missing an obstructed inguinal or femoral hernia might subject a patient to an unnecessary laparotomy when a simple hernia reduction and repair would suffice. Conversely, a missed hernia treated conservatively will put the patient in danger of early strangulation and rapid deterioration.

3. Large-bowel obstruction is frequently caused by a tumour and presents with abdominal distension and a change in bowel habit, depending on the site of obstruction. Classically, left-sided large-bowel obstruction presents with constipation or overflow diarrhoea. Right-sided lesions may present with anaemia or as small-bowel obstruction or with a palpable mass. Perform a digital examination of the rectum in every patient with abdominal distension to assess if there is a rectal mass, faecal impaction or an extraluminal mass or abscess. Large-bowel obstruction is often insidious in onset, and there is usually time to investigate the cause and to differentiate mechanical obstruction from pseudo-obstruction: CT scanning is the investigation of choice.

4. Other causes of large-bowel obstruction include stricture secondary to diverticulitis, ischaemic colitis or rarely Crohn’s disease, and volvulus of the sigmoid colon (and, rarely, of the caecum). Abdominal X-ray shows the classical coffee bean sign in a sigmoid volvulus. Diagnosis of a caecal volvulus is more difficult but a plain X-ray of the abdomen shows dilated caecum in the middle and left side of the abdomen. Volvulus may present fulminantly or subacutely. In subacute sigmoid volvulus a phosphate or gastrografin enema may relieve the obstruction; failing this, employ flexible sigmoidoscopy to decompress the sigmoid colon. Depending on the patient’s general condition and co-morbidities, definitive surgery may be required to fix or resect the redundant bowel to prevent recurrence. In fulminant volvulus perform an emergency laparotomy, resecting the gangrenous sigmoid colon and bringing the proximal end out as a stoma (Hartmann’s resection). This can be reversed at a later date if the patient’s condition permits.

5. Mesenteric ischaemia may present as a catastrophe or as a slowly evolving process. A history of atrial fibrillation or atherosclerotic disease elsewhere is often present in mesenteric arterial occlusion; venous occlusion is rarer and occurs in fulminant pancreatitis and prothrombotic states. A high index of suspicion is necessary for diagnosis, especially in an emergency setting. Sudden onset abdominal pain without signs of peritonism, bleeding per rectum or malaena, metabolic acidosis and rising lactate levels are all suggestive of mesenteric ischaemia and further investigation with a CT angiogram should be done on an emergent basis.

6. Crohn’s disease may cause obstruction through a variety of mechanisms:

Inflammation and oedema may obstruct the lumen in active disease: most patients respond to conservative treatment with steroids.

Inflammation and oedema may obstruct the lumen in active disease: most patients respond to conservative treatment with steroids.

Adhesions between affected segments and other structures may require surgical intervention.

Adhesions between affected segments and other structures may require surgical intervention.

Longstanding disease may result in a stenosed, fibrotic segment causing chronic obstruction and proximal stagnation.

Longstanding disease may result in a stenosed, fibrotic segment causing chronic obstruction and proximal stagnation.

Diagnosis is by contrast-enhanced CT scan or MR enterography. If these modalities are not available, order a conventional small-bowel enema using gastrografin or dilute barium. Treat stenosed segments by resection or stricturoplasty.

7. Radiation enteritis results from progressive vascular and interstitial cellular damage and is dose-related. It most frequently affects the rectum following pelvic irradiation, causing rectal bleeding which is rarely profuse. Small-bowel involvement typically results in chronic strictures and subacute obstruction: the symptoms can be delayed for several years. Treatment is conservative wherever possible, as operative treatment carries a high morbidity and mortality due to poor healing of irradiated tissues.

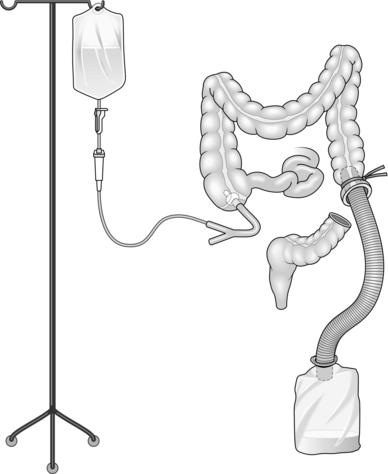

8. Sclerosing peritonitis was historically associated with the beta-blocker practolol, which is no longer used. It is now mainly seen in patients on long-term peritoneal dialysis and, in the tropics, due to tuberculous peritonitis. In some patients no cause may be found (idiopathic sclerosing peritonitis; G idios = one’s own + pathos = suffering). The small-bowel is thickened and encased in a matrix of dense, fibrotic connective tissue, resulting in episodes of subacute obstruction. Once again, pursue conservative management wherever possible as surgery is technically difficult, demanding the utmost patience and skill. The bowel is often oedematous and friable, and there is a significant risk of perforation while attempting to free the matted bowel loops. Plication of the small-bowel in a step ladder fashion has been described with some success in recurrent small-bowel obstruction (Fig. 4.6).

9. Pseudo-obstruction (Ogilvie’s syndrome) presents with episodes of large-bowel obstruction in the absence of a mechanical cause. The cause is not known, although various theories have been proposed. In 1948, Sir Heneage Ogilvie first postulated an imbalance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, and more recent authors have suggested excessive sympathetic tone, decreased parasympathetic tone or a combination of the two. The use of epidural and spinal anaesthesia to relieve pseudo-obstruction supports this theory, as does the beneficial therapeutic effect of guanethidine and neostigmine. Pseudo-obstruction may develop in a wide variety of clinical settings, including:

Intra-abdominal surgery, including urological and gynaecological surgery

Intra-abdominal surgery, including urological and gynaecological surgery

Spinal surgery, spinal cord injury and retroperitoneal trauma

Spinal surgery, spinal cord injury and retroperitoneal trauma

Sepsis and viral infections such as herpes or varicella zoster

Sepsis and viral infections such as herpes or varicella zoster

Neurological disorders, hypothyroidism, electrolyte imbalances such as hypokalaemia, hypocalcaemia, and hypomagnesaemia, cardiac disorders (myocardial infarction, cardiac surgery) and respiratory disorders (pneumonia), renal insufficiency

Neurological disorders, hypothyroidism, electrolyte imbalances such as hypokalaemia, hypocalcaemia, and hypomagnesaemia, cardiac disorders (myocardial infarction, cardiac surgery) and respiratory disorders (pneumonia), renal insufficiency

Medications such as narcotics, tricyclic antidepressants, phenothiazines, antiparkinsonian drugs, and anaesthetic agents.

Medications such as narcotics, tricyclic antidepressants, phenothiazines, antiparkinsonian drugs, and anaesthetic agents.

The clinical presentation may be acute or chronic. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction has an underlying cause in 95% of patients:36 it typically presents with acute, painless and massive distension of the abdomen. Abdominal tenderness may indicate bowel ischaemia or perforation. Plain X-ray of the abdomen will demonstrate dilated colon and CT scan of the abdomen with contrast or gastrograffin enema confirms the diagnosis.

10. Intestinal obstruction following laparotomy may result from temporary oedema of a recently fashioned stoma, a localized collection of fluid, blood or pus, a segment of bowel rendered ischaemic at the operation, an anastomotic leak, wound dehiscence or paralytic ileus. Be prepared to repeat investigations and invite a second opinion from a colleague or senior.

Investigations

1. Blood tests should include a haemoglobin, white cell count, renal function, electrolytes, and liver function tests. Tumour markers (carcino-embryonic antigen and CA 19-9) may be helpful if you suspect colonic cancer. A rising lactate level may indicate strangulated bowel or perforation.

2. Abdominal X-ray and an erect chest X-ray are helpful in determining the presence of bowel obstruction and perforation, respectively.

3. A CT scan usually shows the level and cause of obstruction. In a left-sided large-bowel obstruction, a gastrografin study shows the obstructing lesion and may temporarily relieve the obstruction. You may then undertake colonoscopy and biopsy of the lesion if the patient remains stable with no signs of peritonism or impending perforation.

Prepare

1. In a patient with a distended abdomen that is non-tender and soft, have a nasogastric tube inserted to decompress the bowel. Stop feeding and keep the patient on intravenous fluids and potassium supplements. Introduce a urinary catheter to assess urine output and closely monitor the fluid balance. If there is no improvement in 48 to 72 hours or if there are signs of deterioration (increasing pain, tenderness or peritonism), favour laparotomy. If the condition improves, with decreasing pain and distension, decreasing NG aspirate or passage of faeces and/or flatus, spigot the nasogastric tube, start the patient on a liquid diet and monitor for symptoms or signs of recurrent obstruction.

2. Re-examine the patient after relieving the distension to exclude a mass that was obscured by the tensely distended abdomen.

3. Suspect strangulated bowel in a patient with a tender abdomen, raised inflammatory markers and lactate levels. Be prepared to perform early operative intervention. Carry out urgent laparotomy for closed loop obstruction resulting from an obstruction at two sites (usually a tumour in the distal colon with a competent ileocaecal valve).

4. If the nasogastric aspirate is faeculant or stagnant small-bowel contents, commence broad-spectrum antibiotic cover as these patients are at risk of developing pneumonia.

Assess

1. On entry into the peritoneal cavity, note any free fluid and collect some for bacteriology and, if indicated, for cytology.

2. Introduce a hand into the abdominal cavity, taking care not to injure the distended bowel. Examine the caecum. If it is collapsed the obstruction lies proximally in the small-bowel.

3. Deliver the distended bowel through the wound, ensuring that it is supported at all times by an assistant to avoid traction on the mesentery.

4. Trace the bowel distally to the level of obstruction, dividing any significant bands you encounter.

5. If the vascular supply to the bowel is compromised by a band adhesion, strangulation of a hernia, a volvulus or a closed loop, venous outflow is first impeded while higher pressure arterial inflow continues. Capillaries and venules dilate with stagnating blood losing its oxygen. Eventually small vessels rupture, allowing extravasation visible in the visceral sub-peritoneum. The appearance resembles a bruise. Like a bruise it will take days to be absorbed. As the swelling increases, arterial inflow is halted. The bowel layer with the highest metabolic demand is the mucosa. This becomes porous to fluid and bacteria which rapidly multiply when bowel content stagnates. The submucous, muscular and peritoneal coats survive while the mucosa undergoes necrosis. This is most critical at the constriction rings created by the neck of a hernia – the point at which the vascular restriction and eventual occlusion occurs. Palpable arterial pulsation in the mesentery up to the bowel and a shiny appearance of the visceral peritoneum are reassuring signs.

Action

1. If the obstruction is due to a band adhesion, divide it. Carefully assess the viability of the involved small-bowel, indicated by a return of the normal pink colour. If the bowel is bruised (vide supra) it may still be viable. Wrap a swab soaked in warm saline around the bowel and administer 100% oxygen for 10 minutes, then reassess viability. When in doubt resect the segment and perform an anastomosis rather than risk leaving ischaemic bowel. If there is extensive bowel involvement, or the patient’s condition precludes resection so that bowel of doubtful viability is left behind, be willing to carry out re-exploration at 24–48 hours to reassess the segment in doubt.

2. If you encounter generalized adhesions, carefully begin to divide them by sharp dissection with scissors, taking care not to damage the bowel loops. Any serosal tears should be repaired immediately with interrupted absorbable sutures (2/0 Vicryl or 3/0 PDS). Continue gentle dissection until the site of obstruction is reached and filling of the collapsed distal bowel is observed: patient dissection will usually lead you into the true peritoneal cavity, rendering further dissection easier. You may encounter very dense adhesions, particularly in the pelvis following previous peritonitis, anastomotic leakage or radiotherapy. In these circumstances it may be better to bypass an obstructed loop lying deep in the pelvis rather than attempt a difficult and potentially hazardous dissection. Occasionally you will encounter a ‘hostile’ abdomen where the peritoneal cavity is completely obliterated by dense, fibrotic adhesions, for example following multiple laparotomies, sclerosing peritonitis or radiotherapy (vide supra). Dense, generalized adhesions rarely result in closed loop obstruction and prolonged attempts at dissection are likely to result in a fistula. Attempt a trial dissection of the most accessible bowel loop: if you have made no progress within 20 minutes it is safer to close the abdomen and treat the obstruction conservatively with nasogastric aspiration and parenteral feeding.

3. If the obstruction is due to a missed external hernia, reduce the bowel, confirm its viability and repair the hernial defect. A knuckle of bowel from an internal or external hernia may reduce spontaneously during the laparotomy. If on examining the bowel, there is a constriction ring suggesting this, search for the offending hernia and repair it.

4. Resect a frankly ischaemic segment of bowel or a tumour and undertake anastomosis if the margins are viable and healthy.

5. Bypass an obstructing lesion that cannot be resected. Construct a gastrojejunostomy to relieve pyloric or duodenal obstruction and an entero-enteric anastomosis to bypass a fixed and unresectable small-bowel tumour. Take a biopsy when possible.

6. Treat roundworm bolus conservatively with anti-helminthics. Some authors advocate a hypertonic saline small-bowel enema to purge the worms into the large-bowel: do so cautiously to avoid causing hypovolaemia or bowel perforation. Operate on patients with rectal bleeding (rectorrhagia; G –rhegnynai = to burst) or toxicity and in those who are unresponsive to medical treatment. Massage the bolus of worms towards the colon to relieve the obstruction. You may need to perform an enterotomy to deliver the bolus when there is a volvulus of the bowel, since attempts to milk the worms distally in this situation may cause bowel perforation. Similarly, other intraluminal causes of obstruction such as food bolus, phytobezoar (Greek: phytos = plant) or gallstone will often require an enterotomy to remove the obstructing lesion.

7. When intussusception is the cause of obstruction, reduce it if possible by milking the apex proximally between the thumb and index fingers. If this is not possible or the bowel is not viable, resect the intussuscepted segment. Always look for an underlying cause, such as a polyp or tumour, and remove it.

8. Resect lesions in the right or transverse colon, constructing an end-to-end anastomosis if the patient’s condition and the status of the bowel permit. If left-sided obstruction is diagnosed early, perform a primary resection, on-table lavage37 and primary anastomosis with or without a covering ileostomy. If the obstruction is well-established and the proximal bowel grossly distended and poorly perfused perform a Hartmann’s resection, bringing out the proximal end as a stoma. Close the distal end and leave it in the abdomen. If the tumour is not resectable, create a defunctioning stoma proximal to the obstruction. When gaining consent from a patient to operate for bowel obstruction, always discuss the possibility of stoma formation.

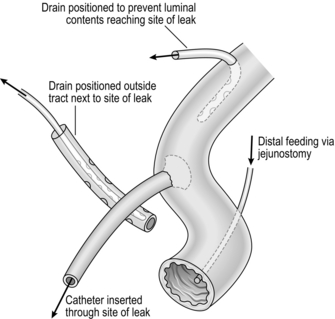

9. To perform on-table lavage, pass a large Foley catheter through the appendix or directly into the caecum (Fig. 4.7). Secure it with a purse-string suture. Distally, tie a length of corrugated anaesthetic tubing into the bowel at the site of proximal resection and connect it to a large plastic bag, forming a closed effluent system. Install normal saline solution via the Foley catheter, milking the bowel contents distally until there are no remaining palpable faecal masses and the effluent is clean. Take down the lavage system and perform a sutured end-to-end anastomosis.

Fig. 4.7 On-table lavage.

10. Management of bowel obstruction in neonates is described in later chapters.

Closure

1. Inform the anaesthetist before attempting to close the abdomen, since adequate relaxation of the abdominal musculature is essential to achieve a sound repair.

2. While dealing with the obstruction you should have achieved decompression of the bowel. If distension remains it is still possible to decompress the bowel by milking the contents proximally into the stomach. Use a nasogastric tube to aspirate the stomach contents.

3. Consider inserting tension sutures, particularly in obese patients.

Aftercare

1. Closely monitor the fluid, electrolyte and acid–base balance.

2. Leave a nasogastric tube in-situ, aspirating at 4-hourly intervals. Remove it as soon as the aspirate diminishes: there is no evidence that leaving an NG tube for a longer time improves outcomes.38 Encourage early feeding as soon as it is tolerated. Re-insert the nasogastric tube if the patient vomits or abdominal distension recurs.

3. Consider giving parenteral (Latin: para = beside + enteron = intestine) nutrition to patients whose dietary intake has been poor for more than a week and in those in whom functional recovery of the intestines may be prolonged.

LAPAROTOMY FOR GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

Assess

1. Assess patients with gastrointestinal bleeding according to ALS protocols, applying a systematic approach to airway, breathing and haemodynamic stabilization. If the patient is bleeding profusely resuscitate aggressively, initially with crystalloid fluids, but give blood transfusion in patients who have lost more than 30% of their circulating volume.39 If the patient remains haemodynamically unstable order an urgent CT angiogram and embolization of the bleeding vessel.

2. Patients with gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding rarely need surgery, and most settle down with conservative measures. Classify them into upper or lower intestinal bleeding; further classify those with upper gastrointestinal bleeding into variceal and non-variceal bleeding. The role of surgery for variceal bleeding has diminished with the advent of potent medications such as somatostatin and the use of transjugular intrahepatic portal systemic shunt (TIPS). Variceal bleeding is not considered further in this chapter.

NON-VARICEAL UPPER GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

1. Common causes include peptic ulceration, gastritis and lower oesophageal (Mallory-Weiss) tear. If these patients with peptic ulcer bleed remain unstable despite resuscitation they need urgent intervention. Coffee ground vomiting suggests a slowly bleeding lesion, whereas fresh blood suggests a peptic ulcer that is bleeding at a rapid rate.

Action

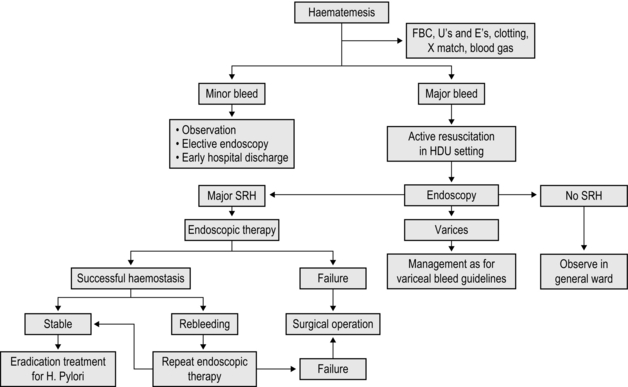

1. If the patient is unstable despite resuscitation or requires transfusions to maintain a normal blood pressure, undertake an urgent endoscopy in the operating theatre. If you can identify the bleeding point and have the appropriate expertise, use injection of adrenaline, diathermy or clips to control it. If a bleeding peptic ulcer is unresponsive to endoscopic measures, proceed to emergency laparotomy (see Fig. 4.8 for guidelines in the management of patients with upper GI bleeding).

Fig. 4.8 Algorithm showing management pathway for upper GI bleed (Adapted from British Society of Gastroenterology Guidelines39). SRH – stigmata of recent haemorrhage.

2. For a duodenal ulcer, open the pylorus and proximal part of the first part of the duodenum with a longitudinal incision along the outer border of the duodenum. Identify the bleeding point, control it with a finger or a swab on a sponge holder and aspirate the remaining blood from the surgical field. At this stage confirm control of the bleeding source by stabilization of the patient’s condition following continued resuscitation. Under-run the bleeding ulcer using a 2/0 Prolene, Vicryl or PDS suture. Confirm that the bleeding has stopped. Close the pylorus and duodenum transversely as a pyloroplasty using interrupted 3/0 Vicryl or PDS sutures.

3. Gastric ulcers rarely bleed. It is more common for gastric erosions to bleed and these almost always stop with conservative treatment. If a bleeding ulcer does not respond to radiological or endoscopic measures, open the stomach along the greater curvature, identify the bleeding point and under-run it as for a duodenal ulcer. Close the gastrotomy with 2/0 Vicryl or PDS. If you suspect malignancy perform a sleeve resection of the ulcer-bearing area and close the defect as for a gastrotomy. Erosive bleeding which fails to respond to conservative measures requires gastrectomy (partial or total as the situation demands).

4. Continue pantoprazole or omeprazole intravenously for the first 48–72 hours. Commence eradication treatment for H-pylori.

LOWER GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

Action

1. Bleeding per rectum causing haemodynamic instability may be due to upper GI or lower GI pathology, therefore carry out an urgent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy to exclude a bleeding peptic ulcer. Bleeding from the lower bowel may be altered or fresh and is usually due to diverticular disease (see Table 4.2 for common causes of lower GI bleeding). Perform digital rectal examination, proctoscopy and sigmoidoscopy to seek causes such as haemorrhoids, polyps, diverticulosis or cancer. Resuscitate the patient with fluids and blood products and correct coagulopathy. In 80% of patients with lower GI bleeding the haemorrhage stops spontaneously and you need only to transfuse blood if necessary and closely monitor the patient.

Table 4.2

Major causes of colonic bleeding

Diverticular disease

Vascular malformations (angiodysplasia)

Ischaemic colitis

Haemorrrhoids

Inflammatory bowel disease (e.g. ulcerative proctitis, Crohn’s disease)

Neoplasia (carcinoma or polyps)

Radiation enteropathy

2. Urgent colonoscopy in acute bleeding is technically difficult, as altered blood in the bowel lumen absorbs light, resulting in poor visualization, and has not been shown to confer any survival benefit.40 For this reason most endoscopists decline to perform a colonoscopy in an acutely bleeding patient. In a haemodynamically stable patient, a nuclear scan (99mTc sulphur colloid or 99mTc labelled RBC scan) is useful when the bleeding rate is as slow as 0.05–0.1 ml per minute, but the test lacks specificity.

3. If the patient is unstable order a CT angiogram. If this demonstrates a bleeding point, proceed to conventional angiography and embolization of the bleeding vessel. The bleeding rate must be at least 1–1.5 ml per minute to be detected on angiography. The procedure may need to be repeated if the patient re-bleeds.