Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass

Surgical Anatomy

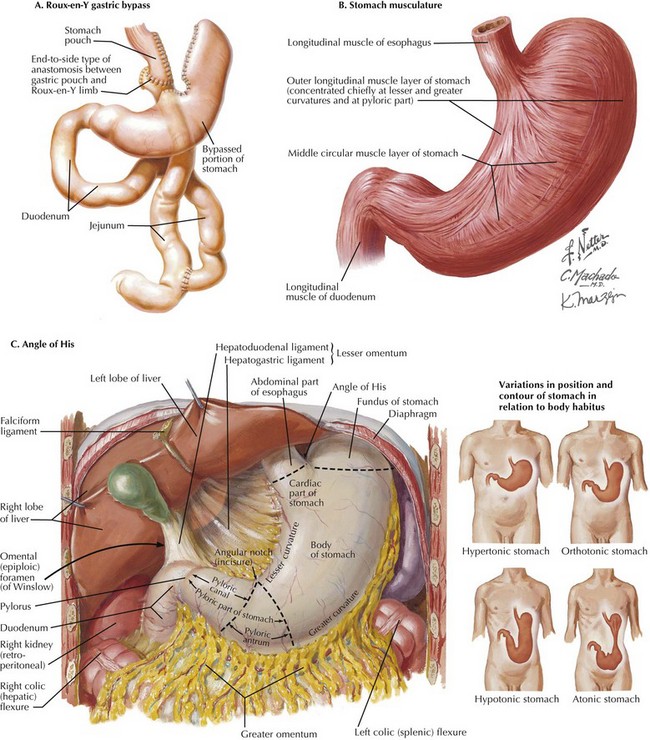

Gastric bypass is the most common bariatric procedure. It has two components, restrictive and malabsorptive, which are both demonstrated in the depiction of a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (Fig. 11-1, A). Because these patients are by definition morbidly obese, the excessive intraabdominal fat can make identification of the anatomy difficult. This chapter describes the anatomic landmarks during Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedure.

The restrictive component of gastric bypass depends on manufacture of a constricted, vertically oriented 20-mL gastric pouch, based on the lesser curvature of the stomach. The lesser curvature musculature is thick and less likely to distend than the fundus of the stomach (Fig. 11-1, B).

Identification and dissection of the angle of His (the angle between the fundus and abdominal esophagus) is a crucial step during construction of the gastric pouch. The angle of His is just to the left of the midline and the gastroesophageal fat pad of Belsey. Transection of the stomach at the angle of His will separate the gastric fundus from the gastric pouch, because the gastric fundus can distend, with resultant weight gain (Fig. 11-1, C). This approach also avoids stapling of the esophagus.

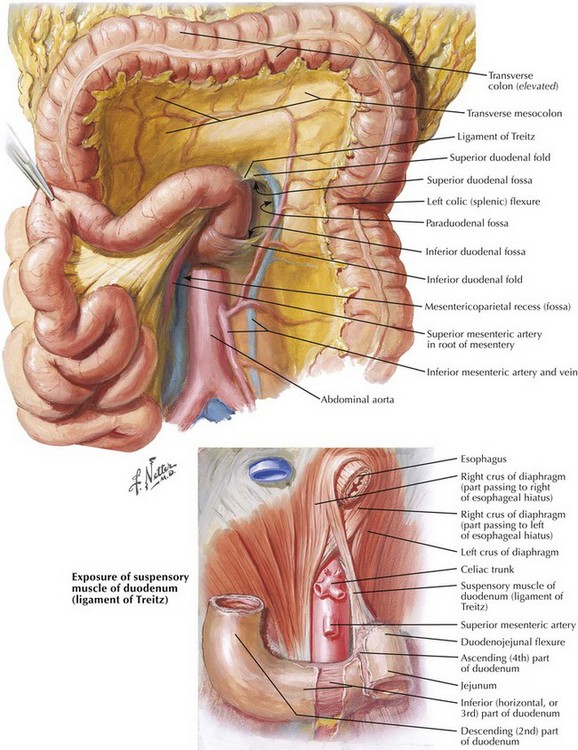

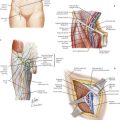

The ligament of Treitz is identified to the left of midline, with the inferior mesenteric vein to its left (Fig. 11-2). On creating a retrocolic path for the Roux limb, a defect in the transverse mesocolon must be anterior and to the left of ligament of Treitz to avoid injury to the middle colic vessels and to the pancreas.

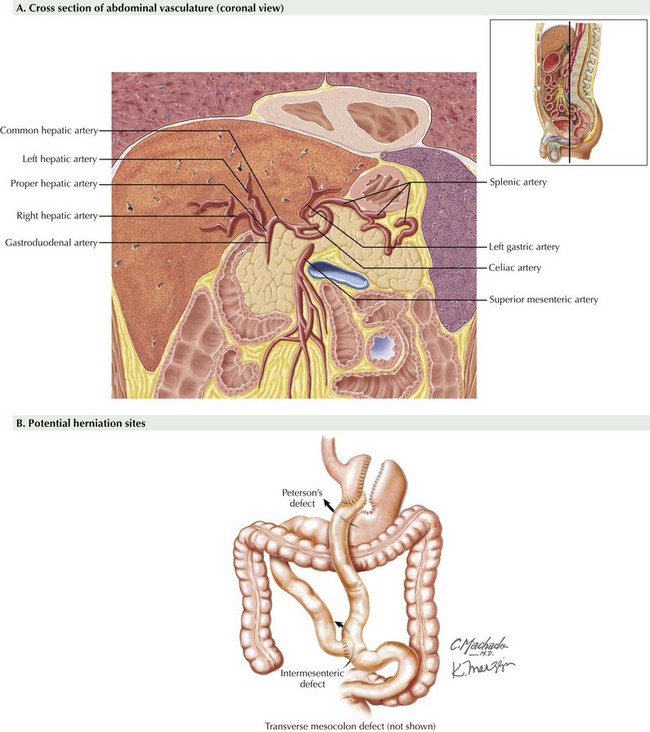

The left gastric artery is the main arterial supply to the gastric pouch, which arises from the celiac artery. Initially, it runs superiorly and to the left to approach the gastroesophageal junction, where it gives rise to esophageal branches, turns inferiorly to follow the lesser curvature of the stomach, and terminates by anastomosing with the much smaller right gastric artery. In 25% of cases, the left gastric artery also gives rise to the left hepatic artery (or accessory left hepatic arteries), which runs through the superior part of the gastrohepatic ligament (Fig. 11-3, A; see also Fig. 6-4).

During Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, several internal defects must be closed with running nonabsorbable suture to avoid internal hernia. These defects include Peterson’s defect (between Roux limb mesentery and transverse mesocolon), intermesenteric defect, and the defect in the transverse mesocolon (in retrocolic technique) (Fig. 11-3, B). Bleeding and leakage may also occur but are minimized with good surgical technique. Late fistulization from the small gastric pouch remnant to the large residual stomach is an unusual cause of failure.

Higa, KD, Boone, KB, Ho, T, Davies, OG. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity: technique and preliminary results of our first 400 patients. Arch Surg. 2000;135(9):1029–1033.

Saber, AA, Jackson, O. Omental wrap: a simple technique for reinforcement of the gastrojejunostomy during Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2007;17(1):15–18.

Sarr, MG. Open Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: indications and technique. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8(4):390–392.