CHAPTER 7 Laparoscopic Nissen Fundoplication and Heller Myotomy

LAPAROSCOPIC NISSEN FUNDOPLICATION

INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

COMPONENTS OF THE PROCEDURE AND APPLIED ANATOMY

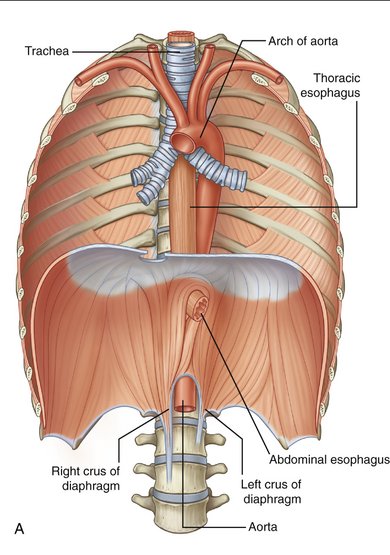

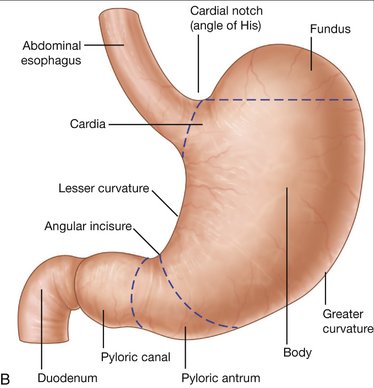

Figure 7-1 Anatomy of the esophagus (A) and stomach (B).

(From Drake RL, Vogl W, Mitchell AWM: Gray’s Anatomy for Students. Philadelphia, Churchill Livingstone, 2005.)

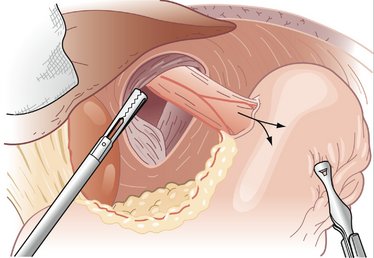

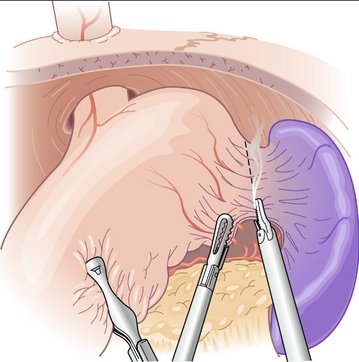

Figure 7-4 Division of the short gastric vessels along the line of transection (dashed line).

(From Townsend CM, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL [eds]: Sabiston Textbook of Surgery: The Biological Basis of Modern Surgical Practice, 17th ed. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2004.)

COMPLICATIONS

LAPAROSCOPIC HELLER MYOTOMY

BACKGROUND

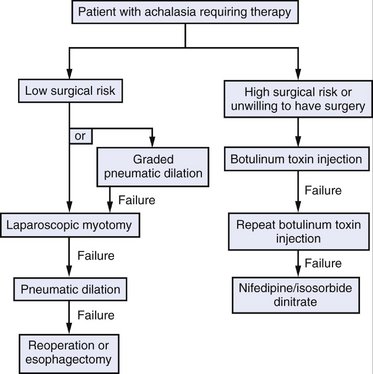

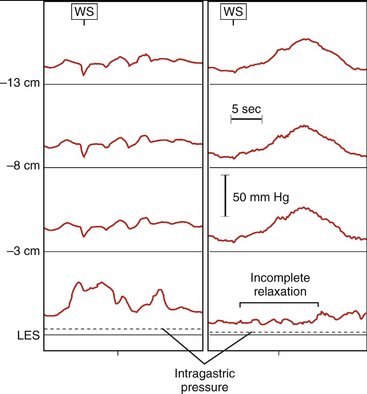

Surgical intervention should be considered for all patients with achalasia; however, two effective nonsurgical therapies are available: pneumatic dilation and botulinum toxin injection. Pneumatic dilation involves passage of a balloon dilator to the level of the LES and disruption of the muscular fibers of the LES through balloon inflation under endoscopic guidance. The vast majority of patients experience symptomatic relief after balloon dilation, but it is frequently short-lived. Additionally, pneumatic dilation is associated with a 5% risk of esophageal perforation. Botulinum toxin inhibits acetylcholine release from the excitatory neurons in the LES, thereby reducing the resting pressure. Injection of botulinum toxin in the area of the LES results in symptomatic relief in the majority of patients, but like pneumatic dilation, this therapy is often transient. Generally, patients at lower surgical risk should be offered surgical myotomy or pneumatic dilation. Patients at high surgical risk should be offered botulinum toxin injection and medical therapies (e.g., calcium channel blockers) aimed at reducing LES pressure (Fig. 7-7).

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

COMPONENTS OF THE PROCEDURE AND APPLIED ANATOMY

COMPLICATIONS

Bonavina L. Minimally invasive surgery for esophageal achalasia. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5921-5925.

Christian DJ, Buyske J. Current status of antireflux surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:931-947.

Oelschlager BK, Eubanks TR, Pellegrini CA. Hiatal hernia and gastroesophageal reflux disease. In: Townsend CM, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, editors. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery: The Biological Basis of Modern Surgical Practice. 17th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004:1151-1168.

Zwischenberger JB, Savage C, Bhutani MS. Esophagus. In: Townsend CM, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, editors. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery: The Biological Basis of Modern Surgical Practice. 17th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004:1091-1150.