Chapter 32 Language Development and Communication Disorders

Normal Language Development

It is customary to divide language skills into receptive (hearing and understanding) and expressive (talking) abilities. Language development usually follows a fairly predictable pattern and parallels general intellectual development (Table 32-1).

| HEARING AND UNDERSTANDING | TALKING |

|---|---|

| BIRTH TO 3 MONTHS | |

From American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, 2005. http://professional.asha.org.

Language and Communication Disorders

Classification

Each professional discipline has adopted a somewhat different classification system, based on cluster patterns of symptoms. One of the simplest classifications is the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) (Table 32-2). This system recognizes 4 types of communication disorders: expressive language disorder, mixed receptive-expressive language disorder, phonological disorder, and stuttering. In clinical practice, childhood speech and language disorders occur as a number of distinct entities.

Table 32-2 DSM-IV DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR COMMUNICATION DISORDERS

EXPRESSIVE LANGUAGE DISORDER

Coding note: If a speech-motor or sensory deficit or a neurologic condition is present, code the condition on Axis III

MIXED RECEPTIVE-EXPRESSIVE LANGUAGE DISORDER

Coding note: If a speech-motor or sensory deficit or a neurologic condition is present, code the condition on Axis III

PHONOLOGICAL DISORDER

Coding note: If a speech-motor a sensory deficit or a neurologic condition is present, code the condition on Axis III

STUTTERING

Coding note: If a speech-motor or sensory deficit or a neurologic condition is present, code the condition on Axis III

COMMUNICATION DISORDER NOT OTHERWISE SPECIFIED

This category is for disorders in communication that do not meet the criteria for any specific communication disorder; for example, a voice disorder (i.e., an abnormality of vocal pitch, loudness, quality, tone, or resonance)

Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, ed 4, Washington, DC, 1994, American Psychiatric Association, pp 58, 60–61, 63, 65.

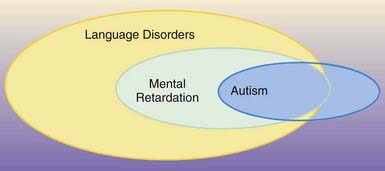

Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders

A disordered pattern of language development is one of the core features of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders (Chapter 28). In fact, the language profile of children with autism is indistinguishable from that in children with SLIs. The key points of distinction between these conditions are the lack of reciprocal social relationships that characterizes children with autism, limitation in the ability to develop functional, symbolic, or pretend play, and an obsessive need for sameness and resistance to change. Approximately 75-80% of children with autism are also mentally retarded, and this can limit their ability to develop functional communication skills. Language abilities can range from absent to grammatically intact, but with limited pragmatic features and/or odd prosody patterns. Some autistic persons have highly specialized, but isolated, “savant” skills, such as calendar calculations and hyperlexia (the precocious ability to recognize written words beyond expectation based on general intellectual ability). Regression in language and social skills (autistic regression) occurs in approximately one third of children with autism, usually before 2 yr of age. No explanation for this phenomenon has been identified. Once the regression has “stabilized,” recovery of function does not usually occur (Fig. 32-1).

Selective Mutism

Selective mutism is defined as a failure to speak in specific social situations despite speaking in other situations, and it is typically a symptom of an underlying anxiety disorder. Children with selective mutism can speak normally in certain settings, such as within their home or when they are alone with their parents. They fail to speak in other social settings, such as at school or at other places outside their home. Other symptoms associated with selective mutism can include excessive shyness, withdrawal, dependency on parents, and oppositional behavior. Most cases of selective mutism are not the result of a single traumatic event, but rather are the manifestation of a chronic pattern of anxiety. Mutism is not passive-aggressive behavior. Mute children report that they want to speak in social settings but are afraid to do so. It is important to emphasize that the underlying anxiety disorder is the likely origin of selective mutism. Often, one or both parents of a child with selective mutism has a history of anxiety symptoms, including childhood shyness, social anxiety, or panic attacks. This suggests that the child’s anxiety represents a familial trait. For some unknown reason, the child converts the anxiety into the mute symptom. The mutism is highly functional for the child in that it reduces anxiety and protects the child from the perceived challenge of social interaction. Treatment of selective mutism should focus on reducing the general anxiety, rather than focusing only on the mute behaviors (Chapter 23). Selective mutism reflects a difficulty of social interaction and not a disorder of language processing.

Motor Speech Disorders

Hearing Impairment

Hearing loss can be a major cause of delayed or disordered language development (Chapter 629). Approximately 16-30 per 1,000 children have mild to severe hearing loss, significant enough to affect educational progress. In addition to these “hard of hearing” children, approximately another 1 per 1,000 are deaf (profound bilateral hearing loss). Hearing loss can be present at birth or acquired postnatally. Newborn screening programs can identify many forms of congenital hearing loss, but children can develop progressive hearing loss or acquire deafness after birth.

Hydrocephalus

Children with hydrocephalus are described as having “cocktail-party syndrome.” Although they may use sophisticated words, their comprehension of abstract concepts is limited, and their pragmatic conversational skills are weak. As a result, they speak superficially about topics and appear to be carrying on a monologue (Chapter 585.11).

Rare Causes of Language Impairment

Screening

At each well child visit, developmental surveillance should include specific questions about normal language developmental milestones and observations of the child’s behavior. Clinical judgment, defined as eliciting and responding to parents’ concerns, can detect the majority of children with speech and language problems. Many clinicians employ standardized developmental screening questionnaires and observation checklists designed for use in a pediatrics office (Chapter 14).

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reviewed screening instruments for speech and language delays in young children that can be used in primary care settings. The Task Force focused on brief measures that require <10 minutes to complete. There was insufficient evidence that screening instruments are more effective than using physician’s clinical observations and parents’ concerns to identify children who require further evaluation. The Task Force noted that there is no single gold standard for screening, owing to inconsistent measures and terminology, and did not recommend the use of screening instruments. Furthermore, the Task Force determined that the use of formal measures was not time or cost efficient and deferred to pediatrician’s and parents’ concerns as indicators of potential problems. Table 32-3 offers guidelines for raising concerns and referring a child for specialized speech and language evaluation. Because of the high prevalence of speech and language disorders in the general population, referral to a speech-language pathologist for further evaluation should be made whenever there is a suspicion of delay.

| REFER FOR SPEECH-LANGUAGE EVALUATION IF: | ||

|---|---|---|

| AT AGE | RECEPTIVE | EXPRESSIVE |

| 15 mo | Does not look/point at 5-10 objects | Is not using 3 words |

| 18 mo | Does not follow simple directions (“get your shoes”) | Is not using Mama, Dad, or other names |

| 24 mo | Does not point to pictures or body parts when they are named | Is not using 25 words |

| 30 mo | Does not verbally respond or nod/shake head to questions | Is not using unique 2-word phrases, including noun-verb combinations |

| 36 mo | Does not understand prepositions or action words; does not follow 2-step directions | Has a vocabulary <200 words; does not ask for things; echolalia to questions; language regression after attaining 2-word phrases |

Diagnostic Evaluation

Psychologic Evaluation

Cohen NJ, Barwick MA, Horodezky NB, et al. Language, achievement, and cognitive processing in psychiatrically disturbed children with previously identified and unsuspected language impairments. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1998;39:865-877.

Cohen NJ, Davine M, Horodezky N, et al. Unsuspected language impairment in psychiatrically disturbed children: prevalence and language and behavioral characteristics. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32:595-603.

De Fosse L, Hodge SM, Makris N, et al. Language-association cortex asymmetry in autism and specific language impairment. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:757-766.

Feldman HM. Evaluation and management of language and speech disorders in preschool children. Pediatr Rev. 2005;26:131-141.

Giddan JJ, Milling L, Campbell NB. Unrecognized language and speech deficits in preadolescent psychiatric inpatients. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1996;66:85-92.

Herbert MR, Kenet T. Brain abnormalities in language disorders and in autism. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54:563-583.

Hill EL. A dyspraxic deficit in specific language impairment and developmental coordination disorder? Evidence from hand and arm movements. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1998;40:388-395.

Kennedy CR, McCann DC, Campbell MJ, et al. Language ability after early detection of permanent childhood hearing impairment. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2131-2140.

Nelson HD, Nygren P, Walker M, et al. Screening for speech and language delay in preschool children: systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e298-e319.

Rapin I, Dunn M. Update on the language disorders of individuals on the autistic spectrum. Brain Dev. 2003;25:166-172.

Reilly S, Onslow M, Packman A, et al. Predicting stuttering onset by the age of 3 years: a prospective, community cohort study. Pediatrics. 2009;123:270-277.

Roberts JE, Rosenfeld RM, Zeisel SA. Otitis media and speech and language: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Pediatrics. 2004;113(3 Pt 1):e238-e248.

Schum R. Language screening in the pediatric office setting. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54:425-436.

Tager-Flusberg H, Caronna E. Language disorders: autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54:469-481.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for speech and language delay in preschool children: recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 2006;117:497-501.

Ward D. The aetiology and treatment of developmental stammering in childhood. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:68-71.

32.1 Dysfluency (Stuttering, Stammering)

Diagnosis

Stuttering must be differentiated from the normal developmental dysfluency of preschool children (Tables 32-4 and 32-5). Developmental dysfluency is characterized by brief periods of stuttering that resolve by school age, and it usually involves whole words, with <10 dysfluencies per 100 words. The DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for stuttering are noted in Table 32-2. Stuttering that persists and is associated with tics may be a manifestation of Tourette’s syndrome (Chapters 23 and 590).

Table 32-4 DIFFERENCES BETWEEN STUTTERING AND DEVELOPMENTAL DYSFLUENCY

| BEHAVIOR | STUTTERING | DEVELOPMENTAL DYSFLUENCY |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency of syllable repetition per word | ≥2 | ≤1 |

| Tempo | Faster than normal | Normal |

| Airflow | Often interrupted | Rarely interrupted |

| Vocal tension | Often apparent | Absent |

| Frequency of prolongations per 100 words | ≥2 | ≤1 |

| Duration of prolongation | ≥2 sec | ≤1 sec |

| Tension | Often present | Absent |

| Silent pauses within a word | May be present | Absent |

| Silent pauses before a speech attempt | Unusually long | Not marked |

| Silent pauses after the dysfluency | May be present | Absent |

| Articulating postures | May be inappropriate | Appropriate |

| Reaction to stress | More broken words | No change in dysfluency |

| Frustration | May be present | Absent |

| Eye contact | May waver | Normal |

Adapted with permission from Van Riper C: The nature of stuttering, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice-Hall, 1971, p 28. From Lawrence M, Barclay DM III: Stuttering: a brief review, Am Fam Physician 57:2175-2178, 1998.

Table 32-5 EXAMPLES OF NORMAL DYSFLUENCY IN PRESCHOOLERS

| TYPE OF DYSFLUENCY | EXAMPLES |

|---|---|

| Voiced repetitions | Occasionally 2 word parts (mi … milk) Single-syllable words (I … I see you) Multisyllabic words (Barney … Barney is coming!) Phrases (I want … I want Elmo.) |

| Interjections | We went to the … uh … cottage. |

| Revisions: incomplete phrases | I lost my. … Where is Daddy going? |

| Prologations | I am Toooommy Baker. |

| Tense pauses | Lips together, no sound produced |

From Costa D, Kroll R: Stuttering: an update for physicians, CMAJ 162:1849–1855, 2000.

Treatment

Preschool children with developmental dysfluency (see Table 32-5) can be observed with parental education and reassurance. Parents should not reprimand the child or create undue anxiety. Preschool or older children with stuttering should be referred to a speech pathologist. Therapy is most effective if started during the preschool period. In addition to the risks noted in Table 32-3, indications for referral include 3 or more dysfluencies per 100 syllables (b-b-but; th-th-the; you, you, you), avoidances or escapes (pauses, head nod, blinking), discomfort or anxiety while speaking, and suspicion of an associated neurologic or psychotic disorder.

Grizzle KL, Simms MD. Language and learning: a discussion of typical and disordered development. Curr Prob Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2009;39:168-189.

Johnson CJ, Beitchman JH, Young A, et al. Fourteen-year follow-up of children with and without speech/language impairments: speech/language stability and outcomes. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 1999;42:744-760.

Peterson RL, McGrath LM, Smith SD, et al. Neuropsychology and genetics of speech, language, and literacy disorders. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54:543-561.

Rinaldi W. Pragmatic comprehension in secondary school-aged students with specific developmental language disorder. Int J Lang Comm Dis. 2000;35:1-29.

Sharp HM, Hillenbrand K. Speech and language development and disorders in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2008;55:1159-1173. viii

Shevell MI, Majnemer A, Webster RI, et al. Outcomes at school age of preschool children with developmental language impairment. Pediatr Neurol. 2005;32:264-269.

Simms MD. Language disorders in children: classification and clinical syndromes. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54:437-467.

Simms MD, Schum RL. Preschool children who have atypical patterns of development. Pediatr Rev. 2000;21:147-158.

Spinath FM, Price TS, Dale PS, et al. The genetic and environmental origins of language disability and ability. Child Dev. 2004;75:445-454.

Stromswold K. The genetics of speech and language impairments. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2381-2383.

Trauner D, Wulfeck B, Tallal P, et al. Neurological and MRI profiles of children with developmental language impairment. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000;42:470-475.

Verned SC, Newbury DF, Abrahams BS, et al. A functional genetic link between distinct developmental language disorders. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2337-2345.

Webster RI, Majnemer A, Platt RW, et al. Motor function at school age in children with a preschool diagnosis of developmental language impairment. J Pediatr. 2005;146:80-85.

Webster RI, Shevell MI. Neurobiology of specific language impairment. J Child Neurol. 2004;19:471-481.