CHAPTER 13 Language and Speech Disorders

Language and speech sound disorders are a heterogeneous group of conditions that limit age-appropriate understanding and/or production of symbolic human communication. Child language disorders are defined in large part by the components of the language system adversely affected (see Chapter 7D): vocabulary, morphology, syntax, semantics, pragmatics, or combinations of these components. Speech sound disorders are conditions in which speech sounds, fluency, and/or voice and resonance are abnormal. Further differentiation of these disorders is based on detailed analysis of the characteristics: (1) underlying cause, such as hearing impairment, cognitive deficits, or genetic syndromes, and (2) prognosis. Multiple components of language and speech may be affected in a single individual.

DEVELOPMENTAL DELAYS IN LANGUAGE AND SPEECH

Prognosis

The term delay implies that children will eventually catch up with typically developing peers. In the case of language development, approximately half of the children who have language delay at age 2 years eventually function in the normal range by the time they reach ages 3 to 4 years.1,2 Research has not identified good predictors of which children with early delays are likely to continue to exhibit later language disorders. A favorable prognosis at early stages has been loosely associated with age-appropriate receptive language skills and symbolic play.3 Of interest is that children with the most severe initial difficulties are not necessarily those whose language delays persist. More research is needed to learn more about predictors and risk factors for long-standing communication difficulties.

Delays during the preschool period that are severe and limit age-appropriate functioning in learning, communication, and social relatedness may warrant classification as a disorder. Children with persistent language problems at school entry are likely to continue to experience difficulties throughout childhood. At that age, persistent delays may be better conceptualized as language disorders. The prevalence of such disorders has been estimated to be as high as 16% to 22%.5 However, other estimates at early school age are approximately 7% for language disorders and approximately 4% for speech disorders.5 Some children whose early delays in language and speech apparently resolve during the preschool years demonstrate reading disorders at school age, which implies that the initial delay was indicative of a fundamental, although subtle, long-standing disorder.6,7

Cause

The precise cause of early delays in language or speech development is not known. A large study of same-sex twins in the United Kingdom revealed that early delays in language development had low heritability, which was suggestive of strong environmental influences, whereas persistent delays had high heritability, suggestive of strong genetic influences.8 Consistent with these findings are studies demonstrating that the amount and type of parental input is positively correlated with rates of language development.9,10 In addition, children with persistent language delays are likely to have family histories positive for language and speech disorders.11,12 How environmental factors interact with genetic predisposition has not been elucidated.

Family members or professionals sometimes assume that clinically significant language delays in toddlers and young preschoolers are temporary because they are associated with one of three factors: the child is a boy, second or third born, or being raised in a bilingual environment. None of these is an adequate explanation for clinically significant delays, nor is any reliably associated with resolution of the delays. Studies document that boys develop language more slowly than girls do in the preschool period. However, the magnitude of the difference is approximately 1 to 2 months, below the threshold of clinical significance.13 Boys are also more likely than girls to develop speech and language disorders and therefore should be evaluated promptly if clinically significant delays are identified. The research literature is inconsistent with regard to the effect of birth order on language development. Some studies reveal modest delays in the early stages of language development on particular measures or aspects of communication.14,15 These weak effects have been attributed to environmental factors, such as the possibility that higher birth order results in reduced child-directed adult input and/or confusion because of three-way communication. If the degree of delay is substantial, then the prudent course of action is assessment.

Finally, being raised in a bilingual environment generally does not slow the process of language learning. Some investigators who compare bilingual children with monolingual children find that bilingual children have smaller vocabularies if only one of their two languages is assessed. However, the differences between bilingual and monolingual children disappear when the total vocabulary of the bilingual children—that is, the number of words in both languages—is compared with the single vocabulary of the monolingual children.16 Early in development, children in bilingual environments may show language mixing or code switching, a tendency to use words from both languages in a single short sentence.17 This language mixing occurs primarily when children do not know the target word in the language of the sentence. Differentiation of the two languages is facilitated when clear environmental cues are associated with each language, such as when one parent consistently uses one language and the other parent uses the other language or when the child reliably hears one language at home and the second language at school. Children from bilingual environments may show uneven skills in the two languages, depending on the amounts of exposure to each language. Bilingualism should be conceptualized as a continuum of proficiencies.16 Children from bilingual households may also have language and speech disorders. Significant delays or deficits in the language of children in bilingual households may signal a possible language disorder, rather than a difference in communication skills related to bilingual input, and warrant evaluation.

Management

Because it is very difficult to predict accurately which children with delays in early language skills are destined to improve and which are likely to have language disorders, children with clinically significant delays are often referred for treatment. Children may qualify for federally funded early intervention services, particularly if the language delay is substantial or accompanied by other developmental delays. For children who do not qualify for early intervention, referral to a speech and language pathologist is advisable to determine whether treatment is warranted. Children whose rate of learning increases and who catch up with typically developing peers can be discharged from treatment; children whose rate of learning remains behind their peers will have had the benefit of early treatment.

LANGUAGE DISORDERS

A language disorder represents impairment in the ability to understand and/or use words in context. Language disorders take many forms. Children may produce or understand only a limited number of words, relying on words that occur frequently in the language or those that are easy to produce. They may demonstrate grammatical immaturities or irregularities in the way that they compose sentences or may fail to understand or accurately produce sentences with complex structures, such as passive voice or embedded clauses. They may exhibit poor understanding of the meaning of words, sentences, or connected discourse or may use words, sentences, and discourse in idiosyncratic ways. Finally, they may use unusual intonation patterns, fail to clearly distinguish questions from statements, or violate rules of polite conversation. Such problems can result in an inability to fully comprehend or express ideas. Language assessment can be used to confirm clinical impressions of a language disorder, specify the components of language affected, determine treatment approaches, and monitor progress during treatment (see Chapter 7D).

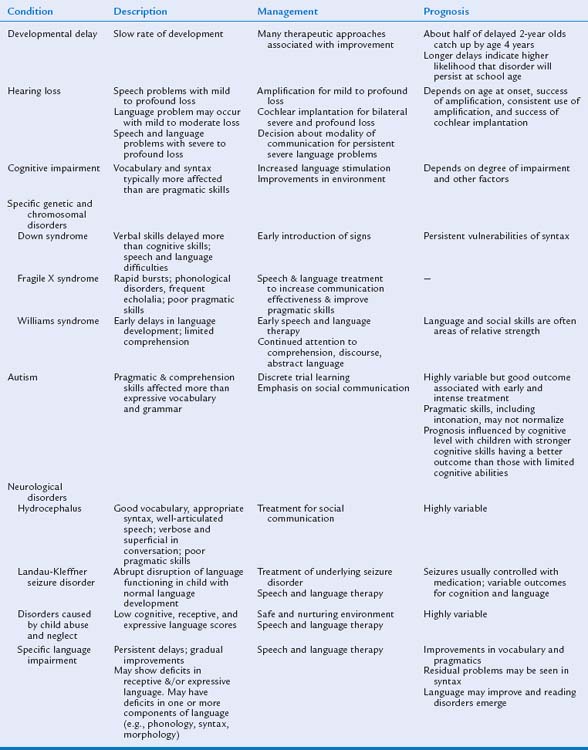

In some situations, an underlying cause of the language disorders may be discovered. The most likely causes are hearing loss, global cognitive impairment, autistic disorders, neurological injuries, and psychosocial disorders (child abuse, child neglect, or environmental deprivation). In children with no known cause of language impairments, specific language impairment (SLI) or simply language impairment is diagnosed. We discuss the effect of the potential causes on the patterns of language and communication and then describe characteristics of SLI (Table 13-1).

Known Causes of Language Disorders

HEARING LOSS

Sounds are described in terms of intensity (decibels), which is associated with the psychological experience of loudness, and frequency (Hertz), which is associated with the psychological experience of pitch. (See Chapter 10F for more detail on hearing impairments.) Normal conversation averages 40 to 60 dB in intensity and clusters in the range of 500 to 2000 Hz in frequency. Some speech sounds, including vowel sounds and consonants /m/, /n/, and /b/, are of low frequency and high intensity, and thus they are relatively easy to hear. Other sounds, such as consonants /s/, /f/, and /th/, are of high frequency and low intensity, and thus they are relatively hard to hear.

Language and speech development in children with hearing impairment depends on many factors, including the degree of hearing loss (mild, moderate, severe, or profound), whether the loss is unilateral or bilateral, the age at identification, the age at receiving amplification, and the consistency of use of amplification. Since the late 1990s, most states in the United States have adopted universal neonatal hearing screening.18,19 As a result of these policies, many cases of sensorineural hearing loss are detected in the neonatal period. The current public health standard in most states is for these children to receive amplification by 6 months of age, a dramatic improvement over the era when hearing loss was often not detected until language delays were identified at ages 2 to 3 years. An intriguing research questions is whether introduction of this public policy will result in better language and speech outcomes for children with hearing loss.

Another major advance in clinical practice for children with bilateral severe to profound hearing loss is cochlear implantation, the use of a prosthetic device to allow perception of the auditory signal. Cochlear implantation changes the prognosis for speech and language skills in many children with hearing loss, although factors such as the age at implantation and the quality of environmental input after implantation are relevant to outcomes (see Chapter 10F for more detail on hearing impairments).20 For children with severe to profound hearing loss who are not candidates for cochlear implantation, whose parents have elected not to give them cochlear implants, or for whom cochlear implantation has not produced successful outcomes, the decision about the type of communication—oral, total communication (sign language plus verbal language), or sign language—must be made.

Children with mild to moderate hearing loss have variable outcomes in terms of language. Some have normal vocabulary skills, demonstrate sentence comprehension, and achieve literacy, whereas others have difficulty with multiple aspects of language.21 In addition to the variables related to treatment of the hearing loss, the degree of hearing loss, the child’s success at phonological discrimination, and the child’s phonological memory are related to his or her language skills.21 Children with mild to moderate sensorineural hearing loss are likely to have a speech disorder (described later in this chapter).21

Research on the effect of recurrent or chronic otitis media on language development has yielded conflicting results. Association studies reveal that children with fluctuating conductive hearing loss from otitis media with effusion have language and speech disorders.22 However, prospective studies find that these associations are short-lived or caused by other factors, including the quality of the language environment.23,24 In addition, randomized clinical trials of tympanostomy tubes for persistent middle ear effusion have not revealed that prompt tube insertion improves the outcomes for language or speech in comparison with delayed or no tube insertion. These results suggest that the associations of otitis media and unfavorable outcomes may have been spurious or that both conditions are related to common underlying factors.25

COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT

Moderate, severe, and profound mental retardation are often associated with a single biological cause, such as genetic disorders, metabolic diseases, or neural malformation. With treatment services language skills can be improved; however, the prognosis for language skills is less favorable than in mild retardation. Social interactions with typically developing peers and speech and language therapy may also improve functional communication. Some chromosomal and genetic conditions that are associated with cognitive impairment are also associated with distinctive behavioral phenotypes in terms of language.

Down Syndrome

Down syndrome results from an extra copy of chromosome 21, usually manifested as a trisomy. Children with Down syndrome, whose cognitive impairment is often at the mild to moderate level of mental retardation, display more significant delays in the early phases of language development than would be predicted on the basis of their cognitive abilities or mental age.26 The rate of language development in children with Down syndrome is often uneven, with long periods of plateau followed by spurts of change. In general, expressive skills are more severely affected than receptive skills.27 As the children with Down syndrome grow older, receptive language and vocabulary knowledge often approach the level of nonverbal intelligence. However, children with Down syndrome have a particular vulnerability in the acquisition of grammar. For example, the mean length of sentences is shorter than what would be predicted on the basis of their mental age. The proportion of verbs is lower than expected for vocabulary size, and the children have difficulty including morphemes, such as a plural “-s” or past tense “-ed.” In addition to language deficits, some children with Down syndrome also have deficits in speech skills. Even during the late school-age years and adulthood, their speech may be very unintelligible or characterized by dysfluent speech patterns.28

The reason for the language phenotype in children with Down syndrome is largely unknown. Although many children with Down syndrome have mild to moderate conductive or mixed conductive-sensorineural hearing losses, hearing loss contributes only a small amount to the variance in language abilities.29 Parental language directed toward children with Down syndrome differs in some ways from that directed toward children developing typically, even those matched for language level. However, this factor alone does not explain the expressive language delays and speech dysfluency. Auditory and verbal memory deficits may also contribute to the language disorder in children with Down syndrome,29 although such deficits may actually be the result of the language disorder. The language of children with Down syndrome resembles the language of children with SLI, described later. One interesting theoretical possibility that must be investigated in future research is whether the cause of the language disturbance in both clinical populations is related.26

From a clinical perspective, children with Down syndrome should be enrolled as early as possible in early intervention services. Because of the delayed development of expressive language and because of the frustration and behavioral problems that sometimes result, early intervention for many children with Down syndrome includes exposure to manual signs, as well as verbal language.30 The goal is to launch a process of communication from which verbal language can develop. Typically developing children use brief actions associated with objects as gestural labels shortly before they express their first words, which suggests that the manual modality may be easier to comprehend or learn than the verbal modality.31 The long-term effect of this educational strategy has not been well studied.

Fragile X Syndrome

The fragile X syndrome is a genetic syndrome caused by a trinucleotide repeat on the X-chromosome, with a resulting cascade of abnormal processes. The fragile X syndrome is associated with cognitive impairment in boys and girls. However, the cognitive and social impairment is generally more severe in boys than in girls. Boys with the fragile X syndrome also have a distinctive language profile. At a young age, the first signs of impending language difficulties include oral hypotonicity, poor sucking and chewing, and lack of control of saliva. Development of expressive language and emergence of phrase-level communication are also delayed.32 Boys with the fragile X syndrome learn to speak late, although their vocabulary and grammatical skills eventually appear to be consistent with their level of nonverbal intelligence. The rate and rhythm of language are characterized by frequent rapid bursts. Affected children also show accompanying phonological disorders.33 Therefore, their communication is frequently unintelligible to unfamiliar listeners. Boys with the fragile X syndrome also demonstrate echolalia, or repetition of words. The perseveration of the words or sounds at the end of sentences, called palilalia, can become so dramatic that they cannot complete sentences.34

Another characteristic feature of boys with the fragile X syndrome is poor pragmatic skills.34 They are likely either to talk incessantly about a topic, unaware of the effect of the narrow conversational focus on the listener, or to show difficulties maintaining topic, introducing tangential topics into the conversation. Their conversation is often highly repetitive. These language problems are most dramatic in situations in which the child must make eye contact with the listener or when the child becomes anxious. From the theoretical perspective, research on why boys with the fragile X syndrome exhibit this constellation of findings must be investigated. From a clinical perspective, treatment of boys with the fragile X syndrome, like treatment of autism, focuses on improving the communication functions of language. However, more research into the efficacy and effectiveness of such treatment is necessary.

Williams Syndrome

Williams syndrome is a genetic condition caused by a deletion on chromosome 7 that is associated with moderate mental retardation; however, affected children show better expressive language skills than would be expected from their cognitive abilities. Language disorders, although also present in other genetic disorders, are not an inevitable feature of mild to moderate mental retardation. Of interest is that children with Williams syndrome may be quite delayed initially in language abilities at a young age and indistinguishable behaviorally from children with Down syndrome, but they use different communication strategies.35 As they develop, language and social skills develop at a faster rate than visual-spatial skills.36 The factors that allow this rapid language development after initial delays are not yet understood. From a clinical perspective, detailed assessment of language and speech in children with Williams syndrome is warranted early in life because of significant delays and differences in their developmental course. If children develop strong verbal skills as they get older, continued therapy may be advisable because their fluent language skills may mask problems with comprehension of sentences and discourse and with comprehension and use of abstract language concepts. Because expressive language abilities represent a relative strength, these children should be supported so that as adolescents and young adults, they can use these strengths for obtaining employment and participating fully in community life.

AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDERS

Autism is a severe neurobehavioral disorder, defined in terms of a triad of behavioral symptoms: qualitative impairment of social interaction; qualitative impairments in communication; and restricted, repetitive, and/or stereotyped patterns of behavior, interests, and activities (see Chapter 15 for more information). Diagnoses of autism are increasing in prevalence, in part because of changing definitions of the disorder.37 Accordingly, autism is in clinical practice becoming more frequently used as the explanation for language delays in children in the first 3 years of life and children with autism are becoming a larger proportion of the case load of speech/language pathologists. Autism should be considered in children with language delays or regression in the language and social domains.

Autism is currently conceptualized as a spectrum disorder.38,39 In the most severe cases, children totally lack a means of communication, whether verbal language, sign language, or gestures. They communicate rarely and nonsymbolically. For example, they might drag a parent to a desired object and whine or cry until the parent figures out what they want. These children may eventually learn rudimentary language, but they tend to use their communicative abilities predominantly to meet their needs and wants instead of to participate in social exchanges. They do not, in the most severe manifestation, describe or comment on objects or events that have drawn their attention. This limitation has been described as a lack of joint attention. Failure of joint attention not only characterizes children with autism but can also be a prognostic indicator and a potential intervention goal.40

Prognosis has been shown to improve for children who, early in life, receive structured treatments based on the principles of applied behavioral analysis.41 For children with moderate to severe autism, discrete trial learning is one such approach that has been used successfully as an initial strategy to promote language learning and self-help skills. The method is predicated on the observations that children with autism are poor at observational or social learning and cannot reliably differentiate important from background information. Therefore, the method breaks down complex tasks, such as understanding natural language, into short, uncomplicated activities or trials and provides tangible rewards for successful completion of a task. As the child progresses in terms of receptive and expressive communication, language expectations increase. Another teaching approache focuses on social interactions rather than on behavioral approaches to language development. A third approach utilizes picture symbols to foster communication, capitalizing on the strengths on the visual domain. Treatment features associated with favorable outcomes include intensive involvement, integrating communication goals with social and communication skills, programming for generalization, and integration with typical peers whenever possible.42 However, more research is needed because social communication approaches have not been subjected to careful, large-scale evaluations.

NEUROLOGICAL CONDITIONS

Hydrocephalus

Hydrocephalus, or hydrocephaly, is a condition in which there is an abnormal accumulation of the cerebrospinal fluid, the watery element in and around the brain. Hydrocephalus develops for many reasons, may occur in isolation or in association with other disorders such as myelomeningocele, and may be present at or near birth or may develop as children age. It is usually suspected on the basis of enlarged head circumference and confirmed in neural imaging studies. Language and speech development of children with early hydrocephalus may be impaired as a function of sensory or neurological factors.43 Many children with favorable outcomes of congenital or early-onset hydrocephalus develop diverse vocabularies, appropriate syntax, and well-articulated speech. However, in conversation, they are often verbose and the content of speech is superficial or repetitive. These characteristics have been summarized as “cocktail party speech” to emphasize the impoverished content and cursory treatment of concepts in their conversation. They may also show impairments in processes important for understanding the meaning of discourse. For example, they may have difficulty in understanding abstract terms and figurative language, such as idioms. They may be weak at drawing inferences from facts presented. Thus, their language difficulties are generally in the realms of semantics and pragmatics.43 Their profile is in some ways similar to that of children with Williams syndrome, and the treatment approaches are therefore also similar. In addition, some children with hydrocephalus have language-related academic difficulties, including difficulty with reading comprehension, despite average intelligence.43

Seizure Disorders

Specific seizure disorders have been associated with language disorders. It is unclear whether these are distinct disorders or related conditions. Landau-Kleffner syndrome is a rare acquired seizure disorder that manifests with an abrupt disruption of language functioning in a child who had previously exhibited normal language development. The language disorder is a severe, receptive language disorder that has been called acquired verbal agnosia to emphasize the poor comprehension abilities of affected children. Imaging studies typically show no clear abnormality, and the electroencephalographic (EEG) abnormalities vary.44 Although the prognosis for seizures is generally favorable, the long-term outcomes of cognition and language are highly variable. Clearly more research on this condition is necessary.

Electrical status epilepticus in slow-wave sleep, also known as continuous spike and wave in slow-wave sleep, is another related and rare acquired seizure disorder that affects cognitive and language functioning.44 Most of the children affected were previously normal, although about one third had previous neurological conditions. Age at onset is typically between 5 and 7 years. Atrophy and neural injuries are more likely to be observed on imaging studies of the brain than in Landau-Kleffner syndrome. Language abnormalities may be accompanied by memory disturbances and behavioral disorders of varying severity.

Some children with autism show regression in language, social relatedness, and behavior in association with a seizure or epileptiform EEG pattern. Abnormal EEG findings are also observed in children with autism who have not exhibited regression. Therefore, it is difficult to relate the language disturbance specifically to EEG abnormalities.44

Traumatic Brain Injury

Traumatic brain injury in children is very likely to manifest persistent but variable characteristics, caused by multiple factors, including the severity and location of injury. The features of communication also evolve in the period after injury, in association with additional factors such as the age at injury and the socioeconomic factors of the family. Among children with severe injury, even those who show good recovery of language skills may be left with subtle changes in speech.

Acquired Focal Left Hemisphere Injuries

Children and adults with these injuries may show disturbances in language functioning. Aphasia, a severe acquired language disorder, is associated with left hemisphere injury in about 95% of cases in adults. On this basis, it has been generally accepted that the left hemisphere is the neural substrate for language in most mature language users. Of interest is that children with congenital injuries to the left hemisphere typically do not develop aphasia.45 Indeed, their language and speech skills are only mildly delayed in development and subtly different at older ages. Functional imaging studies of children with congenital left hemisphere injury performing language tasks typically show more activation in the right hemisphere than what is found in children developing typically.46 These findings demonstrate the plasticity of the nervous system for language and speech when neurological injury occurs in early childhood.

CHILD ABUSE AND NEGLECT

Children who have been maltreated are at substantial risk for language delays and deficits. Children who experience physical abuse achieve substantially lower cognitive, receptive language, and expressive language scores on formal measures than do well-matched uninjured controls. Children who experienced neglect without physical abuse are indistinguishable from those who experienced only physical abuse.47 Functional communication deficits in these children are less severe and noticeable than indicated by formal test results or analysis of conversational samples, which suggests that functional assessment measures may be insensitive in this clinical area and should be supported or supplemented by standardized measures of language.

A likely explanation for the findings in children with abuse and neglect is the poor quantity and quality of child-directed verbal language in their environment. In children developing typically and children at high social risk, differences in maternal talkativeness account for a significant proportion of the variance in the rate of vocabulary growth.10 Similarly, the diversity of syntactic structures and the use of polite language, which is associated with longer sentences and placement of auxiliary verbs in noticeable positions at the start of sentences, are associated with the rate of syntactic growth.9 Some children with abuse and/or neglect may have suffered previous neural injuries, which would further contribute to developmental delays and ultimate disorders.

BEHAVIOR DISORDERS

More than half of children with persistent communication disorders develop behavioral disorders and social-emotional problems. In addition, the number of children who have social-emotional and communication deficits increases as language disorders develop across the school-age period.48 Therefore, longitudinal follow-up of such children should include monitoring of the behavioral and emotional status. In addition, many children with behavior disorders have subtle communication difficulties, including poor comprehension and poor expression. In many cases, the communication deficits remain undiagnosed. These children may experience frustration, limited coping skills, and poor self-esteem as a function of these communication difficulties. They may struggle to interact appropriately with peers, family members, and professionals. In some cases, the communication difficulties may actually be expressed as behavioral disturbances or may exaggerate other negative behavioral characteristics. An important issue for children with behavioral disorders is early and appropriate evaluation of communication and referral for services when needed. Professionals in the mental health arena must collaborate actively with speech and language pathologists, educators, and other support staff to create an integrated and effective treatment program.

Speech and language treatment with these children with behavior disorders often focuses heavily on pragmatic skills, as well as receptive and expressive vocabulary.49,50 Treatment incorporating emotional vocabulary for expressing feelings, improving listening skills, and using self-talk to help with self-regulation51 can occur through collaborative exchanges between the professionals providing speech and language treatment and psychological counseling with these children.

Specific Language Impairment

Specific language impairment (SLI), also known as language impairment, is the term used for children with language deficits who meet the following criteria: normal nonverbal intelligence; normal hearing; normal neurological functioning, and normal structure and functioning of the oral mechanism. Although SLI is a heterogeneous disorder, most affected children have greater difficulty with expressive skills than with receptive skills. In fact, children with both receptive and expressive impairment are more severely affected than those with an isolated expressive disorder. Grammatical Skills (including syntax and morphology) are the most vulnerable part of the language system, although the precise grammatical structures that are most vulnerable vary across languages. Some affected children also have difficulty producing speech sounds.11 The prevalence of SLI is 5% to 7% of children entering school.5 The high rates of SLI in families suggest that genetic mechanisms are important.

The underlying processing mechanisms that give rise to SLI are not completely understood. There may be multiple causes and risk factors. In addition to the language issues, some children with SLI have difficulty identifying and discriminating speech sounds. One major theory is that the language deficits are secondary to more fundamental auditory perceptual processes that affect both nonlinguistic and linguistic stimuli.52 A related theory is that these children have difficulty in processing rapid or brief stimuli, whether in the auditory or other sensory systems.53 The results of this processing issue would be most dramatic in speech because discriminations require perception of multiple and rapidly changing stimuli. Results of electrophysiological and functional neuroimaging studies of auditory perception in humans have suggested that two pathways arise from the primary auditory cortex: a ventral stream, which is involved in mapping sound onto meaning, and a dorsal stream, which is involved in mapping sound onto articulation-based representations.54 The ventral stream projects toward the inferior posterior temporal cortex and ultimately links to widely distributed conceptual representations. The dorsal stream connects posteriorly via the inferior parietal lobe or Wernicke’s area and ultimately to the frontal lobes, including Broca’s area. Each pathway is sensitive to different characteristics of the signal and different modes of processing. Differences in the relative balance of information processing between them may explain some of the phenomena of SLI. Most children with SLI show gradual improvement with speech, language treatment, however, language processing, reading, and writing remain areas of relative weakness as they age.

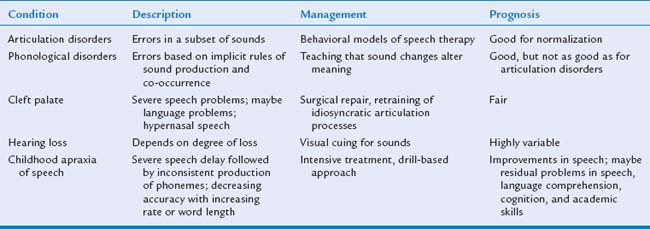

SPEECH SOUND DISORDERS

A speech sound disorder represents impairment in the ability to produce the sounds of the words of the language. The primary symptom of speech impairment is unintelligible speech. Speech disorders are alternatively described in terms of the characteristics of the speech sound errors or the cause of the problem. Speech disorders include problems with articulating sounds, using speech rules (phonological rules), or planning and executing speech sounds. The overall prevalence of such disorders is approximately 4% among 6-year-old children.5 Up to approximately 15% of children with persisting speech delay have evidence of SLI, and up to 8% of children with persisting SLI have speech delays.5 Children with speech sound disorders may also have disorders of voice and resonance or dysfluent speech.

Some speech sound disorders are the result of hearing loss; anatomical abnormalities, such as cleft palate or velopharyngeal insufficiency; or neuromotor disorders. However, in many cases, an underlying cause of the speech sound disorder cannot be identified. Functional articulation disorder is the term for when a child’s speech fails to mature at the rate of that of age-matched peers for no apparent reason. The nature of the speech sound disorder is determined by the characteristics of the child’s speech errors and his or her ability to rapidly move the mouth for nonspeech movements, as well as syllable sequences. The nature of the speech sound disorder affects the treatment process and the prognosis for improvement (Table 13-2).

Phonological Disorders

Treatment of phonological disorders focuses on teaching the child that differences in meaning are conveyed by changes in sound production. Minimal contrast word pairs are used to demonstrate the role of sound in meaning. For example, to treat the rule of final consonant deletion, the speech-language pathologist may engage the child in an activity in which use of the final consonant results in a specific outcome. Minimal contrast word pairs, such as “bow” versus “boat,” “toe” versus “toad,” and “tea” versus “team,” would be incorporated in a game with pictures of these items where the child must say the words with an ending sounds in order to win. In children with severe phonological disorders, 29 treatment sessions, on average, have been shown to have a significant effect on their intelligibility.55

Children with cleft palate are at extremely high risk for phonological disorders, as well as language deficits. Cleft palate may occur in isolation, in conjunction with cleft lip, or in association with other structural and functional abnormalities. Cleft lip may be part of a genetic syndrome, such as velocardiofacial syndrome (deletion 22q11.2), which has a specific behavioral phenotype.56 The outcome of cleft palate depends on the cause and the constellation of coexisting problems. In general, even after early and appropriate repair of an isolated cleft palate, the children remain at risk for problems in speech sound skills. The main problem for these children is that the velopharyngeal structures function abnormally, which results in an inability to generate intraoral air pressure for the production of consonants. Air tends to escape through the nose, which causes what is known as hypernasal speech. Moreover, children with cleft palate often have almost continuous otitis media with effusion and may experience mild to moderate conductive hearing loss. Therefore, the care of children with cleft palate usually requires an interdisciplinary team that includes audiologists and speech-language pathologists, as well as surgeons, dentists, and general pediatricians. Children with cleft lip and/or palate often exhibit unusual or idiosyncratic patterns of articulation, even when they have had surgery at a young age on the palate. For example, they may only produce consonants made in the back of the mouth (e.g., /k/, /g/, /u/) or may use consonants that do not appear in the English language (e.g., pharyngeal fricatives and nasal snorts).

Of importance is that some children experience the soft palate making adequate contact with the oropharyngeal wall during speech, a condition known as velopharyngeal insufficiency.57 These children are at risk for speech sound disorders similar to those of children with cleft palate. The velum is supported in early childhood by the adenoids. As the adenoids shrink with age, the speech disorder may become more obvious. This speech problem is not amenable to the usual articulation therapy and may necessitate surgical correction. In addition, adenoidectomy might exacerbate speech problems in children with velopharyngeal insufficiency. For that reason, otolaryngologists should avoid adenoidectomy in children who have had a cleft palate repair, have a submucous cleft, or have hypernasal speech, which is suggestive of velopharyngeal insufficiency.

Childhood Apraxia of Speech

Childhood apraxia of speech, known alternatively as developmental verbal apraxia or dyspraxia, is a condition in which children have difficulty with the controlled production of speech sounds. Criteria for diagnosis vary among clinicians.58 The first symptoms of apraxia may be a lack of expressive vocabulary despite normal hearing and language comprehension skills. As expressive language emerges, speech may consist of primarily vowel sequences, with very few consonants produced, even in babbling. In childhood apraxia of speech, children produce speech sounds with enormous variability in terms of phonemes, loudness, and related features. The inconsistency in their productions makes interpretation of the sounds very challenging. In addition, these children have difficulties varying the stress in syllables and varying their intonation.58 They may require enormous effort to produce even short phrases. Once they are able to produce a sound correctly in a word, they are not necessarily able to produce the same sound in other words. In some children with apraxia of speech, there is an isolated speech deficit. In some children, it is associated with cognitive, motor, or behavioral abnormalities. In view of the variations in diagnosis, the precise prevalence is not known. In addition, the cause of apraxia of speech is as yet undetermined.

Treatment of childhood apraxia of speech is difficult and must include an intensive schedule of treatment (three to five sessions per week). Children with apraxia have been shown to require 151 sessions of speech treatment, on average, to have a significant effect on the intelligibility of their speech.55 Treatment with these children requires massive amounts of practice, with drill-based activities and teaching of each phoneme and syllable. The intervention helps these children learn to produce sounds in syllables or words of increasing complexity. The preferred approach targets motor learning, multimodality input, and language enrichment. Progress is often slow. Some children with treatment develop normal speech patterns, but many affected children have residual speech sound errors as well as learning disabilities in reading and writing difficulties comprehension.

Stuttering

Stuttering is the most common cause of significant dysfluency, manifested by repetition of sounds and syllables and prolongation of vowels. Stuttering is often accompanied by inappropriate pauses, repetitive facial expressions, or other behavioral routines. Sometimes other motor mannerisms are found in conjunction with stuttering. Approximately 1% of people stutter, and the prevalence is higher in boys and men than in girls and women.59 The degree of stuttering is highly variable across people, ranging from a mild annoyance to a severe disruption of speech. The degree of stuttering is also highly variable within individuals, subsiding in relaxed conversation and flaring on the telephone or during public speaking. Stuttering disorders may co-occur with speech sound disorders and/or language disorders. They are also not uncommon in children and adults with developmental disabilities resulting from cognitive impairments.

Voice and Resonance

Voice disorders are abnormalities in the production of vocal tone. They include abnormalities in the volume of the voice (inordinate loudness or softness) and also abnormalities of the vibratory quality of the vocal cords (hoarseness or a raspy voice quality). Voice depends on the vibratory characteristics of the vocal folds, setting the air above the level of the larynx into vibrations as well. The intonation and stress patterns of conversation and connected discourse require rapid changes in the delicate laryngeal musculature.

1 Dale PS, Price TS, Bishop DV, et al. Outcomes of early language delay: I. Predicting persistent and transient language difficulties at 3 and 4 years. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2003;46:544-560.

2 Feldman HM, Dale PS, Campbell TF, et al. Concurrent and predictive validity of parent reports of child language at ages 2 and 3 years. Child Dev. 2005;76:856-868.

3 Thal DJ, Tobias S, Morrison D. Language and gesture in late talkers: A 1-year follow-up. J Speech Hear Res. 1991;34:604-612.

4 Beitchman JH, Nair R, Clegg M, et al. Prevalence of speech and language disorders in 5-year-old kindergarten children in the Ottawa-Carleton region. J Speech Hear Disord. 1986;51:98-110.

5 Shriberg LD, Tomblin J, McSweeny JL. Prevalence of speech delay in 6-year-old children and comorbidity with language impairment. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 1999;42:1461-1464. 81

6 Tomblin J, Zhang X, Buckwalter P, et al. The association of reading disability, behavioral disorders, and language impairment among second-grade children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41:473-482.

7 Catts HW, Fey ME, Tomblin J, et al. A longitudinal investigation of reading outcomes in children with language impairments. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2002;45:1142-1157.

8 Bishop DV, Price TS, Dale PS, et al. Outcomes of early language delay: II. Etiology of transient and persistent language difficulties. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2003;46:561-575.

9 Huttenlocher J, Vasilyeva M, Cymerman E, et al. Language input and child syntax. Cogn Psychol. 2002;45:337-374.

10 Huttenlocher J. Language input and language growth. Prev Med. 1998;27:195-199.

11 Tomblin JB, Zhang X. Language patterns and etiology in children with specific language impairment. In: Tager-Flusberg H, editor. Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1999:361-382.

12 Tomblin JB. Genetic and environmental contributions to the risk for specific language impairment. In: Rice MLE, editor. Toward a Genetics of Language. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1996:191-210.

13 Fenson L, Dale PS, Reznick J, et al. Variability in early communicative development. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 1994;59:5-173.

14 Bornstein MH, Leach DB, Haynes OM. Vocabulary competence in first- and secondborn siblings of the same chronological age. J Child Lang. 2004;31:855-873.

15 Hoff-Ginsberg E. The relation of birth order and socioeconomic status to children’s language experience and language development. Appl Psycholinguist. 1998;19:603-629.

16 Gutierrez-Clellen VF. Language choice in intervention with bilingual children. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 1999;8:291-302.

17 Genesee F. Early bilingual development: one language or two? J Child Lang. 1989;16:161-179.

18 Joint Committee on Infant Hearing, American Academy of Audiology, American Academy of Pediatrics, et al. Year 2000 position statement: Principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. Joint Committee on Infant Hearing, American Academy of Audiology, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, and Directors of Speech and Hearing Programs in State Health and Welfare Agencies. Pediatrics. 2000;106:798-817.

19 Task Force on Newborn and Infant Hearing. Newborn and infant hearing loss: Detection and intervention. Pediatrics. 1999;103:527-530.

20 Hammes DM, Novak MA, Rotz LA, et al. Early identification and cochlear implantation: Critical factors for spoken language development. Ann Otol Rhinol Lar-yngol Suppl. 2002;189:74-78.

21 Briscoe J, Bishop DV, Norbury CF. Phonological processing, language, and literacy: A comparison of children with mild-to-moderate sensorineural hearing loss and those with specific language impairment. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2001;42:329-340.

22 Nittrouer S, Burton LT. The role of early language experience in the development of speech perception and phonological processing abilities: Evidence from 5-year-olds with histories of otitis media with effusion and low socioeconomic status. J Commun Disord. 2005;38:29-63.

23 Roberts JE, Burchinal MR, Jackson SC, et al. Otitis media in childhood in relation to preschool language and school readiness skills among black children. Pediatrics. 2000;106:725-735.

24 Roberts JE, Burchinal MR, Zeisel SA, et al. Otitis media, the caregiving environment, and language and cognitive outcomes at 2 years. Pediatrics. 1998;102:346-354.

25 Paradise JL, Campbell TF, Dollaghan CA, et al. Developmental outcomes after early or delayed insertion of tympanostomy tubes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353:576-586.

26 Laws G, Bishop DV. Verbal deficits in Down’s syndrome and specific language impairment: a comparison. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders. 2004;39:423-451.

27 Chapman RS, Hesketh LJ. Language, cognition, and short-term memory in individuals with Down syndrome. Down Syndrome: Research & Practice. 2001;7:1-7.

28 Chapman RS, Hesketh LJ. Behavioral phenotype of individuals with Down syndrome. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2000;6:84-95.

29 Laws G. Contributions of phonological memory, language comprehension and hearing to the expressive language of adolescents and young adults with Down syndrome. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45:1085-1095.

30 Clibbens J. Signing and lexical development in children with Down syndrome. Down Syndrome: Research & Practice. 2001;7:101-105.

31 Bates E, Dick F. Language, gesture, and the developing brain. Developmental Psychobiology. 2002;40:293-310.

32 Spiridigliozzi GL, Lachiewicz A, Mirrett S, McConkie-Rosell A. Fragile X syndrome in young children. In: Layton T, Crais E, Watson L, editors. Handbook of Early Language Impairment in Children: Nature. Albany, NY: Delmar; 2001:258-301.

33 Kau AS, Meyer WA, Kaufmann WE. Early development in males with fragile X syndrome: A review of the literature. Microsc Res Tech. 2002;57:174-178.

34 Cornish K, Sudhalter V, Turk J. Attention and language in fragile X. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2004;10:11-16.

35 Laing E, Butterworth G, Ansari D, et al. Atypical development of language and social communication in toddlers with Williams syndrome. Dev Sci. 2002;5:233-246.

36 Paterson SJ, Brown JH, Gsodl MK, et al. Cognitive modularity and genetic disorders. Science. 1999;286:2355-2358.

37 Barbaresi WJ, Katusic SK, Colligan RC, et al. The incidence of autism in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976–1997: Results from a population-based study [see comment]. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:37-44.

38 Volkmar F, Chawarska K, Klin A. Autism in infancy and early childhood. Annu Rev Psychol. 2005;56:315-336.

39 Volkmar FR, Lord C, Bailey A, et al. Autism and pervasive developmental disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45:135-170.

40 Bruinsma Y, Koegel RL, Koegel LK. Joint attention and children with autism: A review of the literature. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2004;10:169-175.

41 Lovaas OI. The development of a treatment-research project for developmentally disabled and autistic children. J Appl Behav Anal. 1993;26:617-630.

42 Diggle T, McConachie HR, Randle VR. Parent-mediated early intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1). 2003. CD003496

43 Fletcher JM, Barnes M, Dennis M. Language development in children with spina bifida. Semi Pediatr Neurol. 2002;9:201-208.

44 McVicar KA, Shinnar S. Landau-Kleffner syndrome, electrical status epilepticus in slow wave sleep, and language regression in children. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2004;10:144-149.

45 Feldman H. Language learning with an injured brain. Lang Learn Dev. 2005;1:265-288.

46 Booth JR, MacWhinney B, Thulborn KR, et al. Developmental and lesion effects in brain activation during sentence comprehension and mental rotation. Dev Neuropsychol. 2000;18:139-169.

47 Barlow KM, Thomson E, Johnson D, et al. Late neurologic and cognitive sequelae of inflicted traumatic brain injury in infancy. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e174-e185.

48 Baltaxe C. Emotional, behavioral, and other psychiatric disorders of childhood associated with communication disorders. In: Layton T, Crais E, Watson L, editors. Handbook of Early Language Impairment in Children: Nature. Albany, NY: Delmar; 2001:63-125.

49 Giddan J, Milling L. Language disorders and emotional disturbance. In: Layton T, Crais E, Watson L, editors. Handbook of Early Language Impairment in Children: Nature. Albany, NY: Delmar; 2001:19-36.

50 Prizant B, Meyer E. Socioemotional aspects of language and social-communication disorders in young children. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 1993;2:56-71.

51 Brinton B, Fujiki M. Social interactional behaviors of children with specific language impairments. Topics Lang Disord. 1999;19:49-69.

52 McArthur GM, Bishop DV. Speech and nonspeech processing in people with specific language impairment: A behavioural and electrophysiological study. Brain Lang. 2005;94:260-273.

53 Tallal P. Improving language and literacy is a matter of time. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:721-728.

54 Hickok G, Poeppel D. Dorsal and ventral streams: A framework for understanding aspects of the functional anatomy of language. Cognition. 2004;92:67-99.

55 Campbell TF. Functional treatment outcomes in young children with motor speech disorders. In: Caruso AJ, Strand EA, editors. Clinical Management of Motor Speech Disorders in Children. New York: Thieme; 2001:385-396.

56 Wang PP, Woodin MF, Kreps-Falk R, et al. Research on behavioral phenotypes: Velocardiofacial syndrome (deletion 22q11.2). Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000;42:422-427.

57 Willging JP. Velopharyngeal insufficiency. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;11:452-455.

58 Shriberg LD, Campbell TF, Karlsson HB, et al. A diagnostic marker for childhood apraxia of speech: the lexical stress ratio. Clin Linguist Phon. 2003;17:549-574.

59 Craig A, Tran Y. The epidemiology of stuttering: The need for reliable estimates of prevalence and anxiety levels over the lifespan. Adv Speech Lang Pathol. 2005;7:41-46.