17 Land Based Rehabilitation and the Aging Spine

Before focusing on the rehabilitation essentials, we will dedicate some time to reviewing the pathophysiologic basis of the degenerative spine, as has been elegantly described by Kirkaldy-Willis.1 A thorough understanding of spinal anatomy and the process of degeneration will better equip us to grasp the focus of rehabilitation exercises tailored for specific pathologic findings in the degenerated spine. Comorbidities are a significant factor influencing the shape and depth of rehabilitation, therefore it is necessary to review common comorbidities encountered when determining a rehabilitation program, and how to adjust it based on these confounding factors. Finally, before reviewing the essential core stabilization exercises, we would like to touch on the normal physiology involved in stabilizing the spine. With this background, we can better understand the kinematics and kinesiology of the exercises reviewed.

The “Degenerative Cascade”

Currently, the most widely accepted theory of intervertebral disc degeneration pathophysiology is a three-stage approach described by Kirkaldy-Willis.1 Stage I describes the acute pain of an initial insult occurring in the early 20 to 30 years of life. This is the beginning of what Kirkaldy-Willis described as the “degenerative cascade.” Repetitive microtrauma to the vertebral endplates results in ischemic events that can compromise the nutritional and metabolic transport to the disc. This microtrauma may also be responsible for an alteration in proteoglycan content resulting in decreased disc hydration and subsequent load-bearing capacity. Clinically, the patient will present with intermittent and self-limiting pain. However, the pain experienced may be extremely debilitating because of the innervation of the outer third of the annulus by the sinuvertebral nerve.

Stage II, or the instability stage, represents continued disc dehydration and loss of disc height. Increased force transfer to the annulus occurs with the subsequent loss of disc height.1 This stage occurs later in life, between 30 and 50 years of age, and the patient presents with periods of low back pain which is usually more intense and protracted in duration.

Stage III, known as the stabilization stage, usually occurs in the 60 and older population. There is continued end-stage tissue damage and attempts at repair. Disc resorption leads to disc collapse, endplate destruction, fibrosis, and osteophyte formation. The patient usually presents with symptoms of neurogenic claudication or radiculopathy from central, lateral recess, and/or foraminal stenosis.1

The Focus of Rehabilitation

A conservative approach is usually warranted, considering the patient population’s comorbidities. Any form of aerobic activity should be structured to provide adequate rest and minimal imposition of joint stress.2 Initiating resistance training under close supervision with the least amount of resistance can provide significant benefit in the aging population.3 As with younger individuals, functional range of motion is extremely important and all aspects of physical therapy should be preceded by appropriate stretching and warm-up to prevent further injury.

Much has been reported on the appropriate amount of rest a patient with acute back pain should adhere to. What has become clear is that excessive immobility will translate to decreased aerobic capacity, impaired flexibility, loss of muscle strength, and promotion of bone demineralization, all of which will exacerbate and promote further pain and disability.4 Ultimately limiting bed rest to a short period proves to be less detrimental than extended periods of bed rest, even in the population of patients who exhibit radiculopathic symptoms.5

Pathophysiologic Basis for Rehabilitation

The goal of exercise for the treatment of acute back pain is pain control. Therefore initiating exercises based on which direction of motion either increases or reduces pain will provide more positive outcomes.6,7 Movement into flexion or extension will centralize low back pain and reduce the patient’s symptoms.

Extension-based exercises, or McKenzie exercises, may be effective in reducing discogenic pain8 by alleviating pressure on the posterior annular fibers and thereby altering intradisk pressure,9 which will concurrently allow anterior migration of the nucleus pulposus10 and subsequent decreased tension on the nerve root.11 Contraindications to extension-based exercises include segmental instability, bilateral sensory or motor deficits, large or uncontained herniations, or an increase in radiculopathic symptoms. If the patient responds well to extension exercises and demonstrates centralization of his or her pain, repeated extension posturing while standing and use after sitting or forward bending is stressed. If the patient does indeed have segmental instability, manual blocking of extension at that level can be achieved by the therapist, and the patient can be educated on preventing segmental mobility.

Flexion-based exercises, or Williams exercises, may be effective in decreasing zygapophyseal joint compressive forces, thus alleviating the compressive load to the posterior disc, decompressing the intervertebral foramen, stretching hip flexors and paraspinal musculature, and strengthening core stabilizers, such as the abdominals.12 Included in flexion-based exercises are pelvic tilts, which can be performed either with bent knees, straight legs, or standing, depending on the comfort level of the patient. These exercises will help decompress the zygapophyseal joint and help mobilize the pelvis for sacroiliac joint dysfunction.

When dealing with patients with idiopathic scoliosis it is widely understood that therapeutic exercises cannot prevent the progression of the curvature; however, there is a clear role for rehabilitation in this setting. The fundamental goal is to prevent the progression of secondary morbidities. Exercises to restore range of motion and strength should begin early. The patient will benefit from exercises that focus on improving trunk posture and alignment, which may prevent the development of a pathological curve. Abdominal and gluteal strengthening helps prevent deconditioning and atrophy, whereas lower extremity hip flexor stretching works well to prevent contractures.13

Physiologic Factors of Spinal Stabilization

Stability of the lumbar spine requires both passive stiffness, through the osseous and ligamentous structures, and active stiffness, through musculature. Any injury to the passive supporting network of the spine will result in instability.14 That is why optimal muscle strength can protect the damaged spine from repetitive shear forces or nonphysiologic weight bearing. The thoracolumbar fascia acts as a physiologic corset, in essence providing a link between the lower limb and the upper limb, supporting the spinal segments and providing proprioceptive feedback to the individual. Therefore a comprehensive stabilization or facilitation of the abdominal, pelvic, and trunk muscles, which attach to the thoracolumbar fascia and provide for flexion, extension, and rotation of the spine, is a key component to improving trunk strength and preventing future exacerbation of pain.

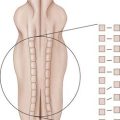

Stabilization of the spine progresses through a sequence of events that begins with strengthening of the smaller intersegmental local muscles of the lumbar spine, such as the multifidi and transversus abdominis. The multifidi usually span a few segments and thereby have a poor mechanical advantage as a significant mover of the spine, but they do play a role in rotational movement and balancing of the shear forces of the spine.15,16 Initial exercises focus on obtaining isolated control of these muscles without substitution.

The next phase of stability training focuses on neutral spine stabilization exercises, regarded as the “safe,” pain-free position.17 A neutral spine position decreases tension on ligaments and joints, appropriate segmental forces with respect to the disc, and the zygapophyseal joint provides optimal stability with axial loading and gives the patient the greatest level of comfort. The neutral spine is located through various body positions, which is followed by lower extremity exercises initially without resistance, then with resistance while maintaining a neutral spine. This approach will help facilitate coordination, endurance, and strength.

Core Stabilization Exercises

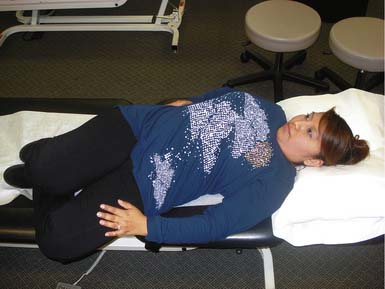

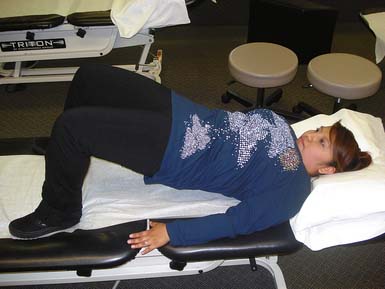

Figures 17-1 and 17-2 demonstrate abdominal strengthening exercises, showing proper activation of the muscles around the abdominal area to support the low back in static and dynamic positions. Daily dynamic load bearing causes the muscles to contract around the viscera to form a stable core region against which the forces are balanced, in coordination with posture.

Figures 17-3 to 17-5 demonstrate back and buttock exercises, which along with abdominal training help control movement, transfer energy, shift body weight, and move in any direction. Weak core muscles result in loss of lumbar lordosis and postural deficiency. Stronger, more balanced core musculature helps maintain appropriate posture and reduce strain on the spine.

Figures 17-6 to 17-8 demonstrate trunk and full body exercises, which are important for proper coordination patterns and abdominal and low back endurance.

1. Kirkaldy-Willis W.H., et al. Pathology and pathogenesis of lumbar spondylosis and stenosis. Spine. 1978;3:319-328.

2. American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription, sixth ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000.

3. Fiatarone M.A., et al. Exercise training and nutritional supplementation for physical frailty in elderly people. N. Engl. J. Med.. 1994;330:1769-1775.

4. Coveretino V.A., et al. Symposium: physiological effects of bed rest and restricted physical activity: and update. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc.. 1997;29:187-206.

5. Vroomen P.C.A.J., et al. Lack of effectiveness of bed rest for sciatica. N. Engl. J. Med.. 1999;340:418-423.

6. Donelson R., et al. Pain response to sagittal end-range spinal motion. A prospective, randomized, multicenter trial. Spine. 1991;16:S206-S212.

7. Stankovic R., et al. Conservative treatment of acute low back pain. A prospective randomized trial: McKenzie method of treatment versus patient education in mini back school. Spine. 1990;15:120-123.

8. Melzack R., et al. Pain mechanism: a new theory. Science. 1965;150:971-979.

9. Nachemson A., et al. Intravital dynamic pressure measurements in lumbar discs: a study of common movements, maneuvers and exercises, Scand. J. Rehab. Med., (Suppl. 1:1970, 1-40.

10. McKenzie R.A. The lumbar spine: mechanical diagnosis and therapy. Waikance, New Zealand: Spinal Publications; 1981.

11. Schnebel B.E., et al. The role of spinal flexion and extension in changing nerve root compression in disc herniation. Spine. 1989;14:835-837.

12. Williams P. Low back and neck pain: causes and conservative treatment, third ed. Springfield, Ill: Charles C Thomas; 1974.

13. Noonan K.J. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: nonsurgical techniques: The pediatric spine: principles and practice, second ed. New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001,. pp. 371–383

14. Ebenbichler G.R., et al. Sensory-motor control of the lower back: implications for rehabilitation. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc.. 2001;33:1889-1898.

15. Crisco J.J., et al. The intersegmental and multisegmental muscles of the lumbar spine. A biomechanical model comparing lateral stabilization potential. Spine. 1991;16:793-799.

16. Panjabi M.M., et al. Spinal stability and intersegmental spinal forces. A biomechanical model. Spine. 1989;14:194-200.

17. Saal J.A. Dynamic muscular stabilization in the non-operative treatment of lumbar pain syndromes. Orthop. Rev.. 1990;19:691-700.