CHAPTER 16 Labor and Birth

FACILITATING LABOR: INDUCTION, AUGMENTATION, AND DYSFUNCTIONAL LABOR

Labor induction refers to the medical stimulation of contractions prior to the onset of spontaneous labor to cause labor to commence.1 One of the most commonly performed obstetrical procedures in the United States, rates of labor induction more than doubled between 1990 and 1998 from approximately 9.5% to 21%.2,3 Reasons cited for this increase include widespread availability of cervical ripening agents, convenience to physicians, pressure from patients, and medico-legal constraints.4 In spite of obstetric recognition that normal human gestation is 40 to 42 weeks (postterm pregnancy is defined as pregnancy past 42 weeks gestation), conservative obstetric practice frequently results in the suggestion, admonition—or insistence—by medical practitioners that their pregnant patients begin labor at, or close to, 40 weeks gestation. Data to support or refute the benefits of elective inductions are limited.4 Risks to the mother and fetus include those related to the medications used, risks of iatrogenically induced prematurity, and the increased risk of operative delivery, which is more likely to occur as a consequence of labor induction.5 According to a Cochrane review of outcomes of labor induction of fetal/neonatal death compared with awaiting spontaneous labor, or a policy of induction after 41 weeks gestation, including a total of 19 trials and over 8000 women, it was reported that there were intranatal and neonatal deaths when a labor induction policy was implemented after 41 completed weeks or later. However, such deaths were rare with either policy.6 In a matched cohort study of 7683 women with elective induced labor compared with 7683 women with spontaneous labor, from 1996 through 1997, cesarean section rates (9.9% vs. 6.5%), instrumental delivery (31.6% vs. 29.1%), epidural analgesia (80% vs. 58%), and transfer of the baby to the neonatal ward (10.7% vs. 9.4%) were significantly more when labor was induced electively.5 Studies from the United States have reported similar findings, with a doubling of operative delivery with induction. 7 8 9 10 Nulliparous women are especially at risk of cesarean section as a result of induction, and an unfavorable cervix at the time of induction appears to be the greatest contributing cause to need for operative delivery.1,7 Elective induction leads to an estimated 12,000 excess cesarean sections per annum at a cost of over $100 million.1 Overall, it is advisable to avoid elective induction unless medically indicated.10

Labor induction should only be undertaken when the benefits to either the mother or fetus outweigh the risks of maintaining the pregnancy.1 Accepted indications for labor induction include:1

Contraindications to labor induction include:1

Labor augmentation refers to the use of medications to stimulate contractions in an already commenced labor when contraction rate or intensity is inadequate to accomplish birth of the baby, or labor has slowed or stopped. Methods of augmenting labor commonly employed by medical professionals include administration of Pitocin via IV drip and artificial rupture of membranes (AROM). Dysfunctional labor is failure to progress in the presence of a normal labor pattern, or the contraction pattern itself may be uncoordinated, leading to ineffectual labor. The results are protracted, stalled, or obstructed labor. Factors contributing to dysfunctional labor include but are not limited to pelvic abnormalities, fetal malpresentation, macrosomic fetus, and maternal sedation.

MEDICAL APPROACHES TO LABOR INDUCTION AND AUGMENTATION

Oxytocin Induction

Synthetic oxytocin (Pitocin) is one of the most commonly used and most potent uterotonic agents available. It is given intravenously for purposes of induction (as an antihemorrhagic, it may be given intramuscularly), in the form of an infusion pump that allows exact dosing with various dosing protocols. Dosing is done incrementally, starting with small amounts and increasing until contractions come at 2- to 3-minute intervals, and typically not exceeding 40 mU/min. Oxytocin is more effective when administered in the presence of a ripened cervix (softening and ability to stretch), thus methods to induce ripening (i.e., prostaglandins suppositories or oral administration, cervical manipulation, amniotomy) may be used just prior to or in conjunction with oxytocin administration. Oxytocin use alone is less effective than prostaglandins for inducing labor. Labor induction with oxytocin is associated with an increased rate of cesarean section.11 Any agent that increases uterine contractions can lead to hypercontractility of the uterus, and can interfere with blood flow to the uterus, and consequently the fetus, with ensuing fetal distress.12 This is a less frequent complication with oxytocin than with misoprostol (see the following). There is some evidence to suggest that use of oxytocin may be associated with an increased incidence of fetal hyperbilirubinemia; however, it is unclear whether this is a direct result of oxytocin use, or associated with other pregnancy factors, such as preterm labor.12

Stripping the Membranes

Stripping the membranes, also called “sweeping the membranes,” is thought to release prostaglandin F2-alpha from the decidua and membranes, or prostaglandin E2 from the cervix, causing cervical ripening and instigating contractions. It is widely used by obstetricians and midwives, often done as a routine part of vaginal and cervical exams in women who are close to or past term, but often undocumented—possibly because it is not generally thought of as an invasive technique by many practitioners (although many midwives do consider it invasive, especially when done without the mother’s permission).1 In a meta-analysis of 22 trials, (n = 2797) 20 comparing sweeping of membranes with no treatment, three comparing sweeping with prostaglandins and one comparing sweeping with oxytocin, risk of caesarean section was similar between groups. Sweeping of the membranes, performed as a general policy in women at term, was associated with reduced duration of pregnancy and reduced frequency of pregnancy continuing beyond 41 weeks and 42 weeks. It is effective at preventing the need for formal induction in one out of eight women. No evidence of a difference in the risk of maternal or neonatal infection was observed. Discomfort during vaginal examination and other adverse effects (bleeding, irregular contractions) were more frequently reported by women allocated to sweeping. Studies comparing sweeping with prostaglandin administration are of limited sample size and do not provide evidence of benefit. The authors of the meta-analysis concluded that sweeping the membranes is effective in some women at inducing labor, and is generally safe in the absence of other complications, and reduces the need for other forms of induction; however, its rate of effectiveness seems limited.13 Weekly membrane stripping appears to shorten the interval of time to spontaneous labor at term, although improvement in pregnancy outcome has not been demonstrated by large, randomized trials.1 Risks of membrane stripping include premature rupture of membranes, infection, disruptions of occult placenta previa and rupture of vasa previa, though these are rare outcomes of this procedure.

Artificial Rupture of Membranes

Artificial rupture of the membranes (AROM), amniotomy, is performed when the cervix is partially dilated and effaced, and with the fetus in a vertex presentation with the head well applied to the cervix to avoid prolapse of the umbilical cord (or other presenting part). Fetal monitoring accompanies the procedure, as does evaluation of the color of the amniotic fluid to detect for the presence of meconium staining—a possible indication of fetal distress. A Cochrane review identified two trials comprising 50 and 260 women, respectively, that were considered eligible for inclusion in the review of amniotomy alone for labor induction. Conclusions were unable to be drawn on the use of amniotomy alone vs. no intervention, nor amniotomy alone vs. oxytocin alone. When compared with single-dose application of vaginal prostaglandins in women with a favorable cervix in a single center trial, a higher rate of oxytocin augmentation was required in the amniotomy alone group (44% compared with 15%). Combined use of amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin is more effective than amniotomy alone. Limited data suggest that the efficacy of oxytocin plus amniotomy is similar to that of prostaglandins alone.14 Amniotomy is associated with an increase in caesarean section rate. With regard to neonatal outcomes, fewer babies are born with Apgar scores of less than seven, but no statistically or clinically significant differences have been observed in other measures of neonatal morbidity, such as umbilical artery acid-base disturbances and admission to intensive care units.15 Risks of amniotomy include intrauterine infection, umbilical cord prolapse, and disruption of an occult placenta previa or vasa previa with subsequent maternal hemorrhage. Serious complications, however, are rare.12

Prostaglandins

Although the exact mechanisms triggering the onset of labor remain unknown, the production of prostaglandins by the body is implicated in the commencement of cervical ripening and stimulation of uterine contractions. Administration of prostaglandins for labor induction is considered preferable to oxytocin use, as the latter does not lead to cervical ripening but only contractions. The use of prostaglandins for labor stimulation appears to decrease the need for obstetric analgesia, and increases the likelihood of birth without operative delivery within 12 to 24 hours of onset of treatment. These advantages, however, are accompanied by increased risk of uterine hyperstimulation with its increased risk of fetal distress and maternal uterine rupture—a surgical emergency. Prostaglandins used include PGE2 and PGF2α; PGE2 is considered safer and equally effective and therefore is the prostaglandin of choice.12 The optimal route, frequency, and dose of prostaglandins have not been determined. 16 17 18 Dinoprostone, either in the form of Cervidil or Prepidil, both FDA-approved drugs for this purpose, is the agent of choice, and is most commonly administered by direct cervical application via vaginal route, as this has proved to be effective with the fewest side effects. Introduction of IV oxytocin approximately 12 hours after administration of dinoprostone is common practice to facilitate labor onset.

Misoprostol (Cytotec) is a synthetic PGE1 analog available as 100- and 200-µg tablets, which can be broken to provide 25- or 50-µg aliquots and can be administered orally or intravaginally. Misoprostol is approved by the FDA for the prevention and treatment of gastric ulcer disease related to chronic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use.1 In most countries, it has not been licensed for use in pregnancy; however, off-label use is common because the drug is inexpensive, stable at room temperature (unlike other prostaglandin drugs), and effective in causing cervical ripening and uterine contractions. Misoprostol is highly effective at initiating labor; reduces the need for oxytocin administration, epidurals, and cesarean section; and shortens time to delivery by as much as 8.7 hours.19 The use of misoprostol has been associated with uterine hyperstimulation, tetanic contractions, precipitous labor, and possibly an increased incidence of uterine rupture, which can be fatal for both mother and fetus.19 Uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate changes and meconium staining of the amniotic fluid—indicative of fetal distress—are increased with misoprostol use. The optimal dose and timing of misoprostol use remain unknown.

Oral misoprostol appears to be more effective than placebo and is at least as effective as vaginal dinoprostone. However, because of increased risk of uterine hyperstimulation and lack of certainty in dosing, vaginal administration, which is also effective, and associated with a slightly decreased risk of hyperstimulation and other side effects compared with the oral route, is considered preferable.19 If misoprostol is used orally, the dose should not exceed 50 mcg.19 In countries where misoprostol remains unlicensed for the induction of labor, practitioners may prefer to use a licensed product, for example, dinoprostone, for legal reasons.19 Studies to date have not been large enough to determine the actual risk of uterine rupture, which has been anecdotally associated with misoprostol use.20 Misoprostol, however, is contraindicated for women with a history of prior cesarean delivery or other previous major uterine surgery owing to increased risk of uterine rupture. Of particular concern also is the use of misoprostol in the home birth setting, where equipment for adequate measurement of uterine contractions is unavailable, as is rapid access to emergency surgery in the event of fetal distress or uterine rupture.

Mechanical Stimulation Methods

Mechanical methods of labor induction include use of a Foley balloon catheter and hygroscopic dilators. In the former method, a Foley balloon catheter is passed, uninflated, into the undilated cervix and then inflated; it may be used alone or in combination with pharmacologic methods of induction. The combination of balloon catheterization and prostaglandin administration appears to significantly increase the likelihood that a woman will deliver within 24 hours of the procedure; however, the benefit of the two methods combined has not been shown to be more effective than use of oral misoprostol alone. Hygroscopic dilators are inserted into the vaginal canal after application of a topical anesthetic, and gradually swell as they absorb moisture. The swelling, in addition to mechanical effects on the cervix leading to dilatation, may serve to disrupt the chorioamnionic decidual interface, causing lysosomal destruction resulting in prostaglandin release. Laminaria, made from seaweed, is a typical hygroscopic dilator; synthetic agents are also available. Hygroscopic dilators do not appear to be as clinically effective as PGE2 gels and are associated with an increased risk of maternal postpartum infection and neonatal infection.1

MEDICAL APPROACHES TO DYSFUNCTIONAL LABOR

The causes of and medical treatments for dysfunctional labor (dystocia) are extensive. This section provides only a brief overview of the pathophysiology and medical interventions. Labor is considered dysfunctional when any of the stages of labor is protracted with no progress made in cervical dilatation and fetal descent. During the latent phase of labor, it is recommended that women alternate rest or sleep with periods of activity (e.g., walking). Cervical effacement, uterine activity, and fetal status are periodically evaluated. Eight-five percent of women progress to the active phase of labor, 10% cease uterine activity, and approximately 5% require oxytocin induction if it is necessary to expedite labor. If labor dysfunction arises during active phases, the underlying reason for arrest is ideally determined; for example, obstruction resulting from a macrosomic baby or contracted pelvis, or fetal head malposition (e.g., persistent asynclitism). Various methods may be used to facilitate labor, including amniotomy, oxytocin infusion, and epidural or other agents to relax pelvic musculature and allow the mother to rest. The fetus is monitored throughout. If fetal status remains normal and there is minimal risk of cord prolapse, ambulation may be allowed or encouraged. If labor does not progress normally with these, and possibly other interventions, or if fetal status becomes compromised, surgical delivery (cesarean section) ultimately must be performed.

BOTANICAL APPROACHES TO FACILITATING LABOR

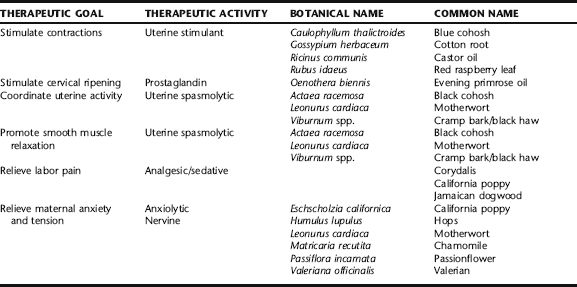

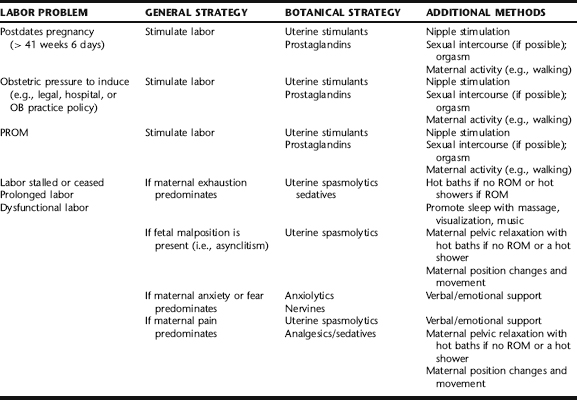

Midwives use a wide variety of approaches to facilitate the onset and progress of labor when these are not occurring spontaneously or when otherwise indicated (Table 16-1). While midwives honor the fact that the timing and pace of labor and birth are highly individual, there are times when legal or medical restrictions require that women birth within certain time parameters, for example, by 41 weeks gestation or within 18 hours of ROM, for women to birth at home in certain states where home birth midwifery is licensed. These constraints require that midwives and their pregnant clients work creatively with a breadth of options in order to expedite labor and birth. Also, birth does not always progress smoothly, obstructed by any number of sometimes benign but nonetheless problematic factors such as malpresentation of the fetal head (persistent asynclitism), maternal fear, anxiety, pain, or pelvic tension. A combination of these factors is very common, as asynclitism can lead to uncoordinated contractions and maternal fatigue, which increase pain, tension, and anxiety—thus creating a vicious cycle that ultimately leads to medical intervention. Often, a combination of agents to alter the maternal response via uterine stimulation or maternal relaxation and noninvasive measures such as nipple stimulation, changes of maternal position, and relaxation techniques can facilitate labor. Rarely is any single technique used in isolation; rather, several techniques are more commonly employed, ideally in an orderly and rhythmic fashion to initiate a healthy, active labor pattern. Botanical choices are selected according to the individual needs and either physiologic or pathophysiologic response to labor, and are used in conjunction with options presented in the section Additional Methods for Facilitating Labor (Table 16-2).

The role of a knowledgeable, supportive care provider, serving as a labor facilitator—a midwife, understanding obstetrician, or doula—cannot be underestimated in its effects on facilitating a healthy labor and birth process. Further, in order to effectively intervene with natural, noninvasive strategies, it is essential that the care provider adequately understand the mechanics, physiology, and psychology of birth. For example, although many think that it is adequate to stimulate contractions in a stalled or dysfunctional labor using uterine stimulants, effective labor required a delicate balance between contraction and relaxation—this yields coordinated uterine contractions, cervical dilatation, and fetal descent. Therefore, it is often more effective to use both uterine stimulant and uterine antispasmodic herbs in combination to achieve an effective labor pattern. Similarly, if a woman is exhausted and contractions are faltering, promoting sleep may actually achieve a better and faster outcome than stimulating contractions. Table 16-2 will help the reader to identify a combination strategy that might be applied to the individual woman. Practitioners must be knowledgeable about when medical intervention becomes required, and of course it is essential that the mother and fetus be adequately and properly monitored during labor, and efforts to stimulate labor. As discussed in the following, blue cohosh, for example, has been associated with rare adverse cardiovascular effects on the fetus, and more commonly with milder side effects as a result of maternal use.

Castor Oil

Castor oil (Fig. 16-1) is a potent cathartic extracted from the castor bean. Use of this herb to stimulate labor appears to date back to ancient Egypt.21 It remains a commonly used folk method to induce labor, and has made its way into obstetric practice, with its use common suggested by midwives. There are scant data evaluating its clinical efficacy. In a clinical trial, a single dose of castor oil was compared with no treatment. There was no evidence of a difference between caesarean section rates, meconium staining of the amniotic fluid, or Apgar score. No data were presented on neonatal or maternal mortality or morbidity. Nausea was a side effect in all women who ingested castor oil.21 Overall, the trial was of poor methodologic quality and no determination can be made regarding efficacy for labor induction.

Blue Cohosh

Caulophyllum thalictroides (blue cohosh) (Fig. 16-2), a native of the eastern and central woodlands of the United States, has been used traditionally and historically as an anticonvulsant, antirheumatic, febrifuge, emetic, sedative, and most notably, a gynecologic aid.22,23 It has been used for labor induction, amenorrhea, dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, and to induce abortion.22 Blue cohosh was official in the United States Pharmacopoeia from 1882 to 1905 for labor induction, and in the National Formulary from 1916 to 1950.24 It was a major ingredient in the popular Eclectic preparation Mother’s Cordial, which also included Mitchella repens, Rubus idaeus, Actaea racemosa, and Chamaelirium luteum. At least one company (Herbalist and Alchemist, NJ) still makes this preparation; however, the blue cohosh has been removed as an ingredient in the product because of safety concerns. The practice of labor induction with blue cohosh remains a popular choice both among self-prescribers and obstetric professionals in the United States and abroad, with one large survey indicating widespread use among nurse-midwives.25 Blue cohosh is listed in the British Herbal Pharmacopoeia (1983) as a spasmolytic and emmenagogue.26 It may also be used as a uterine and ovarian tonic, and for the treatment of a variety of menstrual complaints, including menorrhagia, amenorrhea, dysmenorrhea, and pelvic congestion syndrome.27,28 It is commonly used as a partus preparator to ease parturition, and for labor induction and augmentation.27 It has also been used as an abortifacient.27 Use of blue cohosh during pregnancy is a widespread practice among midwives and pregnant women.25 Maternal ingestion has been associated with a range of fetal and neonatal side effects and adverse outcomes, including fetal tachycardia, increased meconium, profound neonatal congestive heart failure, and perinatal stroke.25, 29 30 31 There is one case report of a neonate born with complications including myocardial infarction and profound congestive heart failure to a mother who ingested blue cohosh as a partus preparator. The newborn remained critically ill for several weeks but eventually recovered. All other causes of myocardial infarction were excluded.30 In another case report, a child was born with severe multiorgan failure associated with the use of a blue and black cohosh combination. The child required significant resuscitation at birth and sustained permanent CNS damage.32 Neither the amount and duration nor preparation used were disclosed. The effects in both cases have been attributed to vasoactive glycosides in the herb. A 21-year-old woman developed symptoms of nicotinic toxicity, including tachycardia, diaphoresis, abdominal pain, vomiting, and muscle weakness and fasciculations after using blue cohosh in an attempt to induce an abortion. These symptoms likely resulted from methylcytosine known present in blue cohosh. The patient’s symptoms resolved over 24 hours and she was discharged.33

Alkaloid and glycoside components in blue cohosh suggest possible mechanisms for these effects, as well as teratogenicity and mutagenicity.33,34 Methylcysteine exhibited teratogenic activity in the rat embryo culture (REC), an in vitro method to detect potential teratogens. Taspine showed high embryotoxicity but no teratogenic activity in the REC.34 Toxic effects of the plant’s constituents include coronary vasoconstriction, tachycardia, hypotension, and respiratory distress.24 However, Low Dog cautions that the quality of the case reports to date and the value of some of the testing methods used to establish toxicity may be questionable. For example, although REC tests have shown teratogenicity and embryotoxicity, “neither the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences nor the Environmental Protection Agency recognizes these tests as an appropriate screen for human reproductive risk.”24 Similarly, it has been speculated that anagyrine, which produces known malformations in ruminant livestock, may do so only after metabolism by microflora in the ruminant gut.24

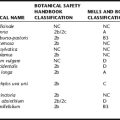

The Botanical Safety Handbook classifies this herb as 2b, not to be used during pregnancy; however, it states that Caulophyllum may be used as a parturient near term to induce childbirth under the supervision of a qualified practitioner.35 Canadian regulations require that any products containing this herb be labeled as not for use in pregnancy.35 Given the volume of blue cohosh use in the United States alone, and the general paucity of reports of its side effects, as well as a lack of comparison of side effects with conventional medications for labor augmentation (i.e., Pitocin, misoprostol), it remains uncertain how great a risk is posed by the use of blue cohosh, particularly for short-term labor augmentation as opposed to long-term use as a partus preparator. Low Dog states, “The human case reports, flawed as they are, paint a picture that is consistent with the evidence provided by the in vitro and animal studies.”24 The most conservative route is to avoid its use entirely as a partus preparator, and possibly at all during pregnancy, until safety information is established. Midwives and mothers choosing to use blue cohosh to augment labor should observe assiduous fetal heart monitoring during use and should discontinue use promptly if deviations are observed. No discussion on the safety of blue cohosh during lactation is reported in the literature.27 One case report in the literature describes an infant born to a mother who had consumed anagyrine containing goat milk; however, as stated, it is not known whether activation of this compound requires metabolism in the ruminant gut.24 Many direct-entry midwives have discontinued use of the herb because of safety concerns.36

The Use of Herbs as Partus preparators and for Labor Induction

The use of herbs for labor stimulation is popular, both with self-prescription among pregnant women and prescribing by midwives.25, 37 38 39 The pressure to give birth by a certain date in order to avoid artificial induction is the primary incentive behind such use, followed by the desire of pregnant women to avoid protracted pregnancy for personal comfort. In a study by Westfall and Benoit, a panel of 27 women was interviewed in the third trimester of pregnancy, and 23 of the same participants were re-interviewed postpartum (50 interviews total). Many of the women said they favored a natural birth and were opposed to labor induction at the time of the first interview. However, all but one of the ten women who went beyond 40 weeks gestation used self-help measures to stimulate labor. These women did not perceive prolonged pregnancy as a medical problem. Instead, they considered it an inconvenience, a worry to their friends, families, and maternity care providers, and a prolongation of physical discomfort.40

A national survey of 500 members of the American College of Nurse-Midwives and 48 nurse-midwifery programs was conducted by McFarlin et al.25 to determine whether they were formally or informally educating students in the use of herbal preparations for cervical ripening, induction, or augmentation of labor. Ninety surveys were returned from CNMs who used herbal preparations to stimulate labor and 82 were returned from CNMs who did not. Of the CNMs who used herbal preparations to stimulate labor 93% used castor oil, 64% used blue cohosh, 63% used red raspberry leaf, 60% used evening primrose oil, and 45% used black cohosh. The most cited reason for using herbal preparations to stimulate labor was that they are “natural,” whereas the most common reason for not using herbal preparations was the lack of research or experience with the safety of these substances. Although 78% of the CNMs who used herbal preparations to stimulate labor directly prescribed them and 70% indirectly suggested them to clients, only 22% had included them within their written practice protocols. Seventy-five percent of the CNMs who used herbal preparations to stimulate labor used them first or instead of Pitocin. Twenty-one percent reported complications including precipitous labor, tetanic uterine contractions, nausea, and vomiting. CNMs who used herbal preparations to stimulate labor were more likely to deliver at home or in an in-hospital or out-of-hospital birthing center than CNMs who never used herbal preparations to stimulate labor.25

Cotton Root

The historical use of cotton root bark as an emmenagogue and abortifacient is discussed in Chapter 5. Ellingwood considered cotton root specifically for uterine inertia, to increase uterine contractions and also prevent postpartum hemorrhage.41 The plant was marketed by Lloyd Pharmaceuticals and Eli Lilly as an oxytocic, emmenagogic agent. The USP listed cotton root as a parturient from 1860 to 1880.42 Cardiotoxic and hepatotoxic effects have been reported in animals and in vitro with gossypol, an isolated chemical constituent used medically. Altered hormone levels and other metabolic effects have been mainly reported in animals and in vitro, but are reported in human studies as well.43 Gossypol is present in the seed in 0.5% concentration, and in lesser concentrations throughout the plant. The root bark extract (not gossypol) is currently used by Western herbalists as an emmenagogue in cases of amenorrhea and as a uterine antihemorrhagic. It is increasingly used by midwives as an alternative or adjunct to blue cohosh as a labor stimulant in postterm pregnancies, for PROM, or for stalled labor. No studies were identified in the literature on use of whole plant extracts, nor the use of this herb for labor stimulation; thus, the safety and efficacy of this herb as a labor stimulant cannot be determined. This herb may have teratogenic effects if taken during early pregnancy, and may induce abortion, so it should not be used earlier in pregnancy than at the intended onset of labor. It is generally given in tincture form, usually in combination with other uterine stimulants, and often antispasmodic herbs. Repeated doses of 2 to 3 mL every 2 hours often result in contractions after four to six doses.

Red Raspberry

Red raspberry leaf is perhaps one of the most historically venerated herbal uterine tonics. It is used during pregnancy to strengthen the uterus, improve labor outcome, and prevent excessive bleeding after birth. Its use continues to be highly popular. One study indicates that approximately 63% of US midwives use this herb to stimulate labor.25 Although it does not appear that raspberry leaf is very effective for labor stimulation or shortening the duration of labor, recent research has found that the consumption of raspberry leaf tea during pregnancy may in fact improve labor outcome and reduce the need for medical intervention at birth. The results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial consisting of 192 low-risk, nulliparous women who birthed their babies between May 1999 and February 2000 at a large tertiary-level hospital in Sydney, Australia found that raspberry leaf, taken in tablet form from 32 weeks’ gestation until labor, caused no adverse effects for mother or baby, and although it did not shorten labor, a lower rate of forceps deliveries between the treatment group and the control group (19.3% vs. 30.4%) was observed.44 Another study consisted of 108 mothers; 57 (52.8%) consumed raspberry leaf products, whereas 51 (47.2%) were in the control group. The findings suggested that raspberry leaf can be taken safely during pregnancy to shorten labor with no expected side effects for women or their babies. The study also reported a decreased likelihood of pre- and postterm gestation, and fewer obstetric interventions, including decreased amniotomy, caesarean section, forceps delivery, and vacuum extraction in the group that had taken raspberry leaf when compared with the control group.45 Herbalists and midwives consider raspberry leaf to be a gentle, effective nutritive medicament, and recommended it be taken in the form of an infusion, 1 to 3 cups daily. Of all the herbs that might be considered for labor preparation, raspberry leaf products appear to be the safest.24

Evening Primrose Oil

Evening primrose oil (EPO) is a rich source of essential fatty acids, especially gamma linolenic acid (GLA), which function as precursors for prostaglandin synthesis. EPO is widely used by many midwives, both applied topically to the cervix and taken orally, to encourage cervical ripening in an effort to shorten labor and decrease the incidence of postterm pregnancies. Sparse data are available to support this use, although many midwives report it to be effective based on observational reports and anecdote (see Case History at the end of this chapter). One study was identified that investigated the effect of oral evening primrose oil on the length of pregnancy and selected intrapartum outcomes in low-risk nulliparous women. A two-group retrospective quasi-experimental design conducted on a sample of women who received care in a birth center, compared selected outcomes of 54 women taking evening primrose oil in their pregnancy with a control group of 54 women who did not. Findings suggested that the oral administration of EPO from the 37th gestational week until birth did not shorten gestation or decrease the overall length of labor. Further, in this study, the use of orally administered EPO may have been associated with an increase in the incidence of prolonged rupture of membranes, oxytocin augmentation, arrest of descent, and vacuum extraction.46 Numerous studies of EPO have found no toxicity. Rare side effects include headache and gastrointestinal upset.47

Black Cohosh

Black cohosh was considered an excellent remedy to treat both “false pains in the pregnant uterus, and aid true pains” making “labor easier and quicker and give a better getting up.”48 One Eclectic physician gave a report to the Chicago Gynecologic Society of a study of 160 primiparous and multiparous women to whom he gave a combination of black cohosh and sarsaparilla during the last 4 weeks of pregnancy. By his account, the women experienced decreased length of labor, with minimal neuralgic cramping and irregular pain in the first stage, greater relaxation of the “soft parts,” energetic and rhythmic contractions throughout the remainder of labor, and decreased incidence of lacerations and good maintenance of contractions after delivery (he compared the effects with those of ergot).49 Black cohosh was an ingredient in the popular Eclectic preparation Mother’s Cordial, which was used as a labor preparatory blend in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It continues to be popular today, with one survey indicating that as many as 45% of nurse-midwives responding to a survey use it to stimulate labor. It is frequently combined with blue cohosh as a popular labor stimulant formula. It is spasmolytic and anti-inflammatory to the smooth and skeletal muscles, making it effective in the treatment of dysmenorrhea, and perhaps suggesting a mechanism for its observed efficacy in treating spasmodic pain in labor and incoordinate uterine contractions.50,51 Black cohosh is approved by the German Commission E for the treatment of premenstrual complaints and dysmenorrhea.52,53 It is indicated for muscular pains, nervous tension, and has been noted to have anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects.54,55 It is often used by midwives to relax spasmodic contractions and help coordinate uterine smooth muscle activity to promote effective contractions in combination with a more stimulating uterine tonic, for example, blue cohosh or cotton root bark (see Blue Cohosh for warnings regarding its use during pregnancy and labor). Several case reports have suggested a possible hepatotoxic effect of black cohosh. As of 2006, several Western nations, including Canada, have issued requirements that all black cohosh products be labeled with a warning about the risk of hepatotoxicity from consumption. The United States has not issued such a warning, based on prior findings that the herb appears reasonably safe. These findings and interpretations are discussed in Plant Profiles: Black Cohosh and should be thoroughly considered when considering whether to use black cohosh during pregnancy or labor. At this time, the safety of the herb for use during pregnancy and lactation is uncertain; long-term use (>2 days) is not advisable. Some herbalists report that patients sometimes experience a frontal headache with use of this herb. If this occurs, discontinue use; this side effect resolves with discontinuation.

Motherwort

Motherwort is considered a uterine spasmolytic and tonic, exerting both actions for the result of easing spastic uterine contractions, for example, in a protracted first stage of labor, while improving the resting tone of the uterine tissue. It is also a favored nervine and anxiolytic, including for panic disorders and to promote sleep. It is widely used by herbalists and midwives during labor, the puerperium, and for PMS-D. Its common name, motherwort, literally means “healing herb for mothers,” suggesting a long history of use for these purposes. Most evidence for the use of motherwort is based traditional medicine, and clinical observation.23,53 No side effects are expected from appropriate use during labor; the herb is considered contraindicated earlier in pregnancy because of its history of use as an emmenegogue.24 It is typically taken in tincture form.

Cramp Bark/Black Haw

Cramp bark, in small doses, was considered by the Eclectics to be an excellent partus preparator, easing irregular uterine contractions and “greatly facilitating a speedy and uncomplicated normal labor.”41 It was also used for after pains and prevention of post-partum hemorrhage, due to tonifying effects exerted on uterine smooth muscle. It was considered specific for erratic uterine cramping and pain.41,56 These herbs are still widely used by contemporary midwives and herbalists for uterine cramping, with many finding it effective for spasmodic contractions and a protracted early labor. Either may be used in tincture form, alone or combined with other herbs as appropriate, for example, nervines or sedatives to promote rest during first stage. Evidence for the uterine antispasmodic effects of these herbs is presented in Plant Profiles: Cramp Bark/Black Haw. There are no adverse effects or side effects expected with use of this herb.

ADDITIONAL METHODS OF FACILITATING LABOR

Nipple Stimulation

Nipple stimulation is commonly recommended by midwives as part of a protocol to stimulate labor. The mother is instructed to apply traction and a pulling, rolling motion to the nipples either simultaneously or separately but sequentially, for 15 to 30 minutes at a time, and repeat this up to two or three times daily for several days if needed. It is more effective to have a partner apply the nipple stimulation, as it is difficult to achieve the required force on oneself. A 2005 Cochrane Review of the effects of breast stimulation on onset of labor identified six trials with a total of 719 women. Analysis of trials comparing nipple stimulation with no intervention found a significant reduction in the number of women not in labor at 72 hours. However, this result was only seen in women with a favorable cervix at the onset of stimulation. Interestingly, a major reduction in the rate of postpartum hemorrhage was reported (0.7% vs. 6%). There was no significant difference in the cesarean section rate (9% vs. 10%), nor in rates of meconium staining. There were no instances of uterine hyperstimulation. Three perinatal deaths were reported.57 Chayen and Kim, in a clinical trial of 317 contraction stress tests using stimulation with an automatic breast pump, found that contractions were successfully achieved in 84.2% of cases, with uterine hyperstimulation observed in 4.1% of tests performed. They reposted that side effects and complications were minimal.58 In another study by Chayen et al., nipple stimulation with an electric breast pump was compared with oxytocin infusion as a means of labor induction. The time from stimulation to the onset of regular uterine activity and to 200 Montevideo units of uterine activity and the time until entrance into the active phase of labor were significantly shorter in the nipple stimulation group. Once the women were in active labor, there was no difference between the groups in the length of labor or mode of birth. Although nipple stimulation is not as effective as oxytocin induction, it appears to be effective for many women, and may be considered a safe, effective alternative to try before turning to pharmaceutical or mechanical labor stimulation.59

Sexual Intercourse

Prostaglandins have been extensively studied for their role in stimulating the onset of labor, particularly, ripening the cervix. Human semen is a rich biological source of prostaglandins, with a high prostaglandin concentration. The use of intercourse to stimulate labor has become a modern “folk” tradition, and it is widely recommended among midwives when labor stimulation is required. The typical recommendation is intercourse two to three times daily, for 2 to 3 days in a row. Of course, this assumes the mother is in a heterosexual, sexually active relationship. The recommendation is generally made in conjunction with additional techniques for labor stimulation (e.g., nipple stimulation, herbs). It is uncertain whether any stimulating effects resulting from sexual intercourse result from the mechanical stimulation of the lower uterine segment, the endogenous release of oxytocin as a result of orgasm, or the direct action of prostaglandins in semen. Furthermore, nipple stimulation may be part of the process of initiation if this occurs in the context of sexual activity. These various factors are very difficult to standardize for clinical studies in comparison with other interventions for labor induction.60 A Cochrane Review identified one study of 28 women, from which the authors determined that no meaningful conclusions could be derived.60 As long as the membranes are intact, there is not placenta previa, and the mother is comfortable with this approach, there is no harm in incorporating intercourse into efforts to stimulate labor.

Acupuncture

Acupuncture has been used in Asia and Europe to decrease the pain of labor, effect cervical ripening, and stimulate the onset of labor. It has been suggested that acupuncture neuronal stimulation may increase uterine contractility either by central oxytocin release or parasympathetic stimulation of the uterus. A Cochrane Review on the effects of acupuncture on labor stimulation found that although there are a number of studies looking at acupuncture labor effects, few are of high quality. Induction of labor using electro-acupuncture was reported by Yip in 1976 with a success rate of 67% of women (n = 31), with pregnancy duration ranging from 38 to 42 weeks. Another study (n = 12) using acupuncture with and without electrical stimulation had a success rate of 83% with an average time between induction and delivery of 13.1 hours. In a third study, 34 term and postterm women and seven women with intrauterine fetal deaths were induced using electroacupuncture. Labor was successfully induced in 32 (78%) women.61 These and a limited number of additional observational studies to date suggest that acupuncture for induction of labor appears safe, has no known teratogenic effects, and may be effective.61 The evidence regarding the clinical effectiveness of this technique is limited.

Homeopathy

Homeopathy is popularly used for labor induction. The homeopathic extract of Caulophyllum thalictroides is proposed to be useful in establishing labor, or when uterine contractions are short and irregular or there is an arrest of uterine contractions.62 It is commonly recommended that pregnant women ingest one tablet daily for the last few days prior to the due date or desired onset of labor, or alternatively to dissolve a tablet in a glass of water and sip from the glass from time to time, or whenever a contraction is imminent. A double-blind placebo controlled matched cohort study by Beer et al. compared Caulophyllum with placebo in 40 women at term with PROM and no onset of contractions. Women were administered Caulophyllum or a placebo hourly for 7 hours. Each active tablet consisted of 250 mg Caulophyllum (trituration D4) and inert binders.63 A study by Dorfman et al. compared five homeopathic therapies with placebo in 93 women from 36 weeks pregnant; 53 women were randomized to the treatment group and 40 to the placebo group. The trial examined the effect of the homeopathic therapy on length of labor and difficulty of labor. The information on any side effects arising from Caulophyllum was unclear and it was unclear as to how women assessed the tolerability of Caulophyllum. No data were provided on side effects.64 The Cochrane Collaboration concluded that both trials were of weak methodologic quality and no meaningful conclusions can be drawn on the efficacy of Caulophyllum for inducing labor or improving labor-related outcomes.65 Additionally, they comment that the use of Caulophyllum may not represent common homeopathic practice, in which the prescribing of a therapy is typically individualized.65 However, it may represent common over-the-counter self-prescribing that is based on more common generic prescriptions, of which it should be noted that the adverse effects that may be associated with the use of the herb blue cohosh (Caulophyllum thalictroides), discussed in the preceding, are not expected with the homeopathic preparation, in which no identifiable chemical compounds remain.

Walking and Positional Changes

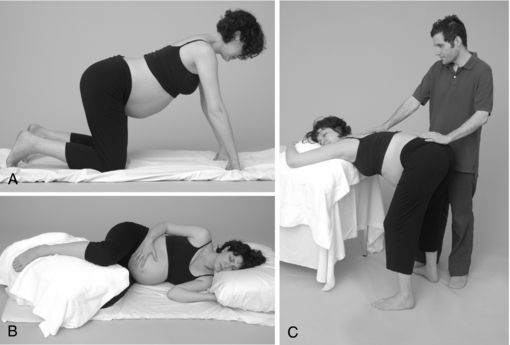

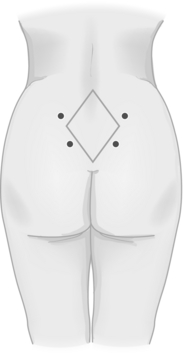

Controversy exists regarding the relationship between maternal position in labor and outcome, such as labor duration, subjective discomfort, and fetal outcome.66 In cultures not influenced by Western society, women progress through the first stage of labor in upright positions and change position as they wish with no evidence of adverse effects to either the mother or fetus.12,67,68 The technologic approach to birth endemic to Western culture with nearly ubiquitous reliance on interventions such as continuous fetal monitoring, epidural use, and continuous IV infusion, relegates women to a supine position during labor. Numerous studies have demonstrated that this position may increase the risk of adverse effects to both the mother and her passenger, as well as impinging on the effective progress of labor.69 Effective contractions, and therefore effective fetal descent and prevention of dystocia, are essential to labor progress and can be facilitated with ambulation and positional changes in labor.12 Further, moving around can increase a woman’s sense of control in labor by providing a self-regulated distraction from the challenge of labor and also may decrease her need for analgesia.69 The use of a variety of position, changes of position throughout labor as needed, and maternal ambulation in labor are considered by midwives to be fundamental to the prevention and management of labor dystocia, particularly when associated with remediable fetal malpresentation, such as asynclitism. Further, changes in maternal position, such as from supine to left lateral or hands-and-knees, can be effective in relieving fetal cord compression and therefore fetal distress associated with the supine position. 70 71 72 73 Midwives frequently encourage positions that are not only physiologic for the mother, her maximal comfort and labor effectiveness, and the position of the fetus, but also positions that facilitate optimal maternal support, such as access to massaging her lower back to relieve the pain of lower back labor (Fig. 16-3).

A limited number of studies evaluate the effects of maternal position on labor outcome, and most of these evaluate positions prescribed by obstetric care providers rather than those chosen by laboring women for themselves.66 In a study by Carlson et al., it was observed that left to select their own positions, a total of 80 laboring patients selected from no less than 59 different positions during the course of labor, with a greater variety of positions chosen in early labor, but more positional changes occurring during second stage. The most commonly selected position for labor was lateral recumbent.66 Outcome measures were not evaluated in this study. The hands-and-knees position during labor has been recommended on the theory that gravity and buoyancy may promote fetal head rotation to the anterior position and reduce persistent back pain and cause rotation of the fetal head when in a persistently posterior position. A Cochrane Review based on two studies found that the use of hands and knees position for 10 minutes twice daily to correct occipitoposterior position of the fetus in late pregnancy does not affect this change; however, it did not evaluate the use of this position during labor or for more extended lengths of time.74 A study by Stremler et al. was conducted to evaluate the effect of maternal hands-and-knees positioning on fetal head rotation from occipitoposterior to occipitoanterior position, persistent back pain, and other perinatal outcomes. Thirteen labor units in university-affiliated hospitals participated in this multicenter randomized controlled trial. Study participants were 147 women laboring with a fetus at 37 weeks gestation and confirmed by ultrasound to be in occipitoposterior position. Seventy women were randomized to the intervention group (hands-and-knees positioning for at least 30 minutes over a 1-hour period during labor) and 77 to the control group (no hands-and-knees positioning). The primary outcome was occipitoanterior position determined by ultrasound following the 1-hour study period, and the secondary outcome was persistent back pain. Other outcomes included operative delivery, fetal head position at delivery, perineal trauma, Apgar scores, length of labor, and women’s views with respect to positioning. Women randomized to the intervention group had significant reductions in persistent back pain. Eleven women (16%) allocated to use hands-and-knees positioning had fetal heads in occipitoanterior position following the 1-hour study period compared with five (7%) in the control group. Trends toward benefit for the intervention group were seen for several other outcomes, including operative delivery, fetal head position at delivery, 1-minute Apgar scores, and time to delivery. The authors concluded that maternal hands-and-knees positioning during labor with a fetus in occipitoposterior position reduces persistent back pain and is acceptable to laboring women and this option of a position for labor should be made available to women laboring with a fetus in occipitoposterior position.75

LABOR STIMULATION PROTOCOL

Midwives use a variety of protocol to stimulate labor. They are applied in a supportive atmosphere conducive to labor, with the primary labor support person(s) present and ideally, appropriate monitoring available for mother and fetuses (e.g., maternal blood pressure and labor progress, fetal heart tones). A typical protocol for initiating labor is presented immediately following in the case history. Other herbs may be added to the protocol, such as nervines if there is anxiety. Women are not encouraged to attempt to stimulate labor prior to 40 weeks, unless otherwise medically instructed, because of the risk of inducing premature labor. The labor initiation protocol is typically applied over an 8-hour time course, and if not effective on the first attempt, it may be repeated the following day. It is not recommended to repeat this for more than two consecutive days. Some mothers find the castor oil intolerably nauseating; if so, repeat the abdominal massage and skip intake; some mothers may experience a frontal headache. This is most likely a result of the black cohosh. Discontinue the tincture for the following does and thereafter substitute cramp bark or black haw for the black cohosh.

At 37 weeks, Alison went to her nurse-midwife who checked her cervix and found it to be uneffaced and undilated. By ultrasound, the baby’s weight was estimated at approximately 8 lbs. Alison followed the instructions for using the EPO and went to her midwife for a follow-up appointment to determine whether any progress occurred with this treatment; she was found to be 50% effaced and 1 cm dilated. At the onset of 38 weeks, Alison followed the 8-hour protocol, ending at about 6 pm. She had dinner with her family and then she and her husband went to a movie. She got to bed at about 11:30 pm and was awakened at about 2 am with strong contractions. These persisted and by about 6 am she could no longer tolerate the discomfort and felt the need to go to the hospital. In her mind, she was disappointed because with her previous labor she had labored for 30 hours and only progressed to 6 cm; now she felt she was giving up already and assumed she would have another cesarean. She arrived at the hospital about 45 minutes later, and was found to be 9 cm dilated. She birthed a healthy 8.5-lb baby boy within the hour, vaginally, and with no complications for the mother or baby. The family was entirely pleased and the nurse-midwife amazed at the efficacy of the herbal protocol. At 7 years old, the last time the herbalist-midwife saw the “baby” mother and child were in excellent health, and the mother still ecstatic over the birth experience.

PAIN IN LABOR

The experience of pain in labor is a complex individual experience, and perhaps one of the greatest areas of anticipatory anxiety for pregnant women. Epidural anesthesia is currently used in almost two-thirds of all labors in the United States, a reflection of the immense desire of women to avoid the pain normally associated with labor.77,78 Although epidural anesthesia can be an invaluable tool in the management of difficult labors and births, and many women report that epidural analgesia is very helpful, it is not without potential risks, including increased length of labor, need for operative vaginal delivery, likelihood of perineal laceration, increased incidence of maternal fever leading to increased use of neonatal antibiotics and sepsis evaluations, increased use of oxytocin augmentation, and possible increase in need for cesarean section.76,78 There are little data evaluating the effects of epidural anesthesia on breastfeeding and mother–infant bonding; however, it has been observed that women who experience operative deliveries are more likely to experience postpartum depression, which can significantly affect mother–child interaction. Women are poorly informed about the potential side effects of epidural (and other) anesthesia, and what little information they are given is commonly provided in active labor, even at the height of a contraction, when it is impossible for a woman to make an informed choice.78 Further, women are rarely offered nonpharmacologic alternatives for pain relief, in spite of the fact that numerous studies show that the use of doulas, continuous labor support, using various positions for labor, massage during labor, sterile water injections, acupuncture, and other modalities lessen labor pain.78

Unlike other chapters in this book, which emphasize the use of botanical therapies, this chapter provides an overview of the many possible options for pain management in labor that are commonly used by midwives and other practitioners, of which herbs are only a small part.

The non-pharmacologic approach to pain includes a wide variety of techniques to address not only the physical sensations of pain but also to prevent suffering by enhancing the psycho emotional and spiritual components of care. Pain is perceived as a side effect of a normal process, not a sign of damage, injury, or abnormality. Rather than making the pain disappear, the midwife and other caregivers assist the woman to cope with it, build her self-confidence, and maintain a sense of mastery and well-being.79

ASSUMPTIONS ABOUT LABOR AND BIRTH: OBSTETRIC VS. MIDWIFERY BELIEFS

According to childbirth sociologist Carol Sakala, a prevalent assumption of the biomedical approach to labor pain is that many or most women require pain medication during labor.76 In direct contrast, midwives assume that women intrinsically know how to birth, and that with adequate prenatal preparation and support during the birthing process, pain medication is often unnecessary.76,80 Midwives recognize that a routine, homogenous approach to pain management in labor, even using nonpharmacologic methods, is inherently ineffective, and that care providers must be able to respond to the unique needs of individual laboring women with a variety of tools in their repertoire, and be creative and responsive in the moment.

Midwives believe that not only is education about the process of labor and birth essential, but so is a close and trusting relationship with their care provider, or in the least, a doula who can be both a support person and an advocate for the mother. Midwifery wisdom appears to be consistent with what women actually report as the most important factors leading to a feeling of satisfaction with birth, none of which include pain relief as important. A recent systematic review concluded that the four factors associated with satisfaction with the childbirth experience are:78

Midwives, whose professional care is based on a mother-centered empowerment approach, and caregivers that include CAM as part of the repertoire they offer mothers for labor support, are more likely to be perceived by patients as consistent with these factors.81

Hospital-based preparation (e.g., childbirth classes), commonly spend more time preparing women for the interventions they can expect as part of routine hospital practices than building their sense of personal empowerment and choice. Childbirth classes designed by midwives (e.g., Birthing from Within) in contrast, are more likely to emphasize skills and tools that can be used by the mother/couple to achieve as natural a birth as possible. Changing medical attitudes to embrace the possibility of natural birth as a routine childbirth practice will be necessary to expand the repertoire of nonpharmacologic interventions available to women birthing in medical institutions. It has been demonstrated in European hospitals that such attitude changes can lead to changes in practice that translate into reductions in unnecessary medical and surgical interventions, improving outcomes for both mother and baby.82 “Hospitals with low cesarean section rates have achieved this goal by embracing the belief that supportive labor care and the least intervention create the best opportunity for a good birth experience.”82

CONTINUOUS LABOR SUPPORT

The word “continuous,” as it relates to labor support, has been defined in various ways. In one study, in which staff nurses were the support providers, “continuous” was defined as “a minimum of 80% of the time from randomization to delivery.” In a meta-analysis of trials of labor support, “continuous” was defined as “without interruption, except for toileting, from shortly after admission to the hospital or entry into the study, and during the birth of the child.” Labor support with a midwife or doula usually includes continuous presence, emotional support (reassurance, encouragement, and guidance); physical comforting (assistance in carrying out coping techniques, use of touch, massage, heat and cold, hydrotherapy, positioning, and movement); information and guidance for the woman and her partner; facilitation of communication (assisting the woman to express her needs and wishes); and nonmedical information and advice, anticipatory guidance, and explanations of procedures.79 Continuous support provided by another woman with birth experience consistently has been demonstrated to reduce labor pain and improve labor outcomes—a fact long known by traditional midwives worldwide. Perhaps the seminal studies on this were reported by Kennell et al., who found that the continuous presence of a supportive companion (doula) during labor and delivery in two studies in Guatemala shortened labor and reduced the need for cesarean section and other interventions. In a US hospital with modern obstetric practices, 412 healthy nulliparous women in labor were randomly assigned to a supported group (n = 212) that received the continuous support of a doula, or an observed group (n = 200) that was monitored by an inconspicuous observer. Two hundred four women were assigned to a control group after delivery. Continuous labor support significantly reduced the rate of cesarean section deliveries (supported group, 8%; observed group, 13%; control group, 18%) and forceps deliveries. Epidural anesthesia for spontaneous vaginal deliveries varied across the three groups (supported group, 7.8%; observed group, 22.6%; control group, 55.3%). Oxytocin use, duration of labor, prolonged infant hospitalization, and maternal fever followed a similar pattern. The authors concluded that the beneficial effects of labor support underscore the need for a review of current obstetric practices.83 A Cochrane meta-analysis found a decrease in operative vaginal deliveries, cesarean section, fewer requests for pain medication, and increased birth satisfaction when continuous labor support was given.84 Interestingly, fear of labor in itself has been shown to decrease pain tolerance.85 The support of a caring woman during pregnancy and in labor, herself educated and experienced in matters of birth, can be instrumental in dispelling and alleviating fear. Prenatally, midwives are aware that they can have a dual role in becoming both a trusted support person, but also someone who can help a woman to reframe or reprogram her misapprehensions and misconceptions about childbirth, so that the mother might enter labor with reduced anxiety.76

MASSAGE

Massage is a tool used almost ubiquitously by midwives throughout labor, whether of the lower back, gentle “effleurage” of the abdomen, or of the legs, neck and shoulders, or forehead (Fig. 16-4). Massage is tailored to the specific physical needs of the mother and her stage in labor; for example, during early labor, a deep foot massage can help a mother to sleep through contractions and get needed rest, in more advanced labor, firm lower back pressure might be welcomed, and during transition, light touch across the forehead can relieve tension. Even just simple touch can be a great comfort.78 Massage can be used throughout labor, with women in a variety of positions from side-lying to standing, and requires no special equipment (although massage oil or hand cream can be used to prevent chaffing or irritation to the mother’s skin). Training in specific massage techniques can be beneficial for optimal relief of discomfort, and is easy to teach the labor partner or for doulas and midwives to learn; however, it is not necessary to have special training to be effective and comforting.

Figure 16-4 Sites for firm acupressure massage or sterile water injections.

Stillerman E: Prenatal Massage: A Textbook of Pregnancy, Labor, and Postpartum Bodywork, St. Louis, 2008, Mosby.

A number of studies have explored the effects of massage on labor pain. In a study by Chang et al., 60 primiparas in labor were randomly assigned to either a massage or control group and tested using the self-reported Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ) at three phases of cervical dilation: phase 1 dilation (3 to 4 cm), phase 2 dilation (5 to 7 cm), and phase 3 dilation (8 to 10 cm). The massage group received standard nursing care and massage intervention, whereas the control group received standard nursing care only. The results of this study showed that in both groups, as cervical dilation increased, there were significant increases in pain intensity as measured by SF-MPQ; that massage lessened pain intensity at phase 1 and 2, but there were no significant differences between the groups at phase 3. The results of this study indicate that, although massage cannot change the characteristics of pain experienced by women in labor, it can effectively decrease labor pain intensity at phase 1 and 2 of cervical dilation during labor.86 Another study evaluated a program of massage, controlled breathing, and visualization performed regularly by birth partners, from 36 weeks gestation and assisted by a trained professional, following hospital admission during labor and birth. The intervention was designed in light of experimental findings that repeated massage sessions over 14 days increases pain threshold, by an interaction between oxytocin and opioid neurons.87 A 4-week time frame was selected to coincide with a physiologic increase in maternal pain threshold. To detect the effects of massage during labor on maternal cortisol and catecholamines, cord venous blood was taken to measure plasma concentrations following birth. Twenty-five nulliparous and 10 multiparous women participated in the study. Cortisol values were similar to published studies following labor without massage, but pain scores on a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), done at 90 minutes after birth were significantly lower than scores recorded 2 days. The mean score was 6.6. Previous studies suggest that a reduction from 8.5 to 7.5 would significantly reduce pharmacologic analgesia in labor. 87 88 89 A study by Field et al. of 28 average socioeconomic women from diverse ethnic backgrounds [Hispanic (57%), white (34%), black (9%)] were randomized to receive massage in addition to coaching or breathing, or to receive coaching and breathing in the absence of massage. Based on self-reporting using a Likert scale, 1 2 3 4 5 women in the massage group reported a pain reduction from 5.0 to 3.5, whereas the women in the control group actually reported an increase from 4.3 to 5.0.90

HYDROTHERAPY

Maternal anxiety and pain may prolong labor and contribute to fetal distress.91 Hydrotherapy during labor can promote relaxation and decrease pain without the risks caused by other treatments. Hydrotherapy can include warm baths, birthing pools, or a hot shower, ideally with an adjustable flow spray nozzle with a firm massage setting. A pilot study by Benfield et al. on the psychophysiologic effects of hydrotherapy on maternal anxiety and pain during labor was conducted. Using a randomized, pretest-posttest control group design with repeated measures, 18 term parturients were assigned to a control or an experimental group. Experimental subjects were placed in a tub of 37° C water for 1 hour during early labor. The Wilcoxon two-sample test revealed statistically significant effects. At 15 minutes, bathers’ anxiety and pain scores were decreased compared with nonbathers. At 60 minutes, bathers’ pain scores were decreased compared with nonbathers. After 15 minutes of immersion, bathers had a significantly greater increase in plasma volume than nonbathers. No significant differences were found in urine catecholamines or maternal–fetal complications. The small sample limits conclusions, but the findings offer preliminary support for the therapeutic effects of bathing in labor for acute, short-term anxiety and pain reduction.91

A review of the literature suggests that a primary effect of immersion is a central blood volume bolus, which occurs almost immediately after bathing begins. Subjective maternal responses to bathing in labor have been favorable. No maternal or infant infections have been attributed to bathing by parturients with either intact or ruptured membranes. Maternal bathing in labor does not appear to affect infant Apgar scores or stress hormones at birth. No clear evidence exists to indicate that hydrotherapy increases cervical dilation, increases fetal descent, reduces uterine dyskinesia, shortens labor, decreases use of epidurals or analgesia, or decreases rates of operative delivery or hemorrhage. Study findings indicate support for using hydrotherapy for relief of rapid pain and anxiety in labor.92 Midwives have observed that the overuse of water, especially full immersion in warm tubs for extended durations during labor, actually can lead to maternal exhaustion and delays in labor. Although there is no way to individualize the amount of time a woman spends in water during labor, personal midwifery experience suggests emphasizing the use of short baths or showers and massage in early labor, and using warm tubs and full immersion at longer lengths in later stages of active labor. Women may enter the water at any point in labor, but when there is cervical dilatation less than 5 cm, bathing may diminish the frequency or intensity of contractions, as may staying in the water for greater than 2 hours continuously.93 Having the mother get out of the tub and walk around and cool off periodically may prevent prolonged labor. To prevent maternal dehydration during long immersions, fluid intake should be encouraged. Immersion in baths is contraindicated in labor when there is evidence of maternal infection, excessive vaginal bleeding, conditions requiring continuous fetal monitoring, with continuous oxytocin infusion, or a nonreassuring fetal heart rate pattern.

AROMATHERAPY

Many midwives and mothers report that soothing scents can enhance a sense of comfort and well-being in the laboring mother’s environment. Scents may be chosen for their relaxing effects (e.g., lavender), soothing effects (e.g., lavender, vanilla), or stimulating effects (e.g., peppermint). Essential oils, distributed via diffuser or spray bottle, may be mixed into massage oil, added to a warm bath, or placed on a washcloth in the bottom of a hot shower. In one extensive observation study of 8058 mothers in childbirth, the largest research initiative in the use of aromatherapy within a health care setting. The study involved a wide range of participants, from mothers who experienced a low-risk, spontaneous labor and birth, to those whose labor was induced, and those who had vaginal operative delivery and cesarean section. The study took place over a period of 8 years, which enabled a more challenging test of the effect of aromatherapy on intrapartum midwifery practice and outcomes. In the study, a total of 10 essential oils were used, plus a carrier oil, which were administered to the participants via skin absorption and inhalation. The study found little direct evidence that the practice of aromatherapy per se reduces the need for pain relief during labor, or the incidence of operative delivery. But a key finding of this study suggests that two essential oils, clary sage and chamomile, are effective in alleviating pain. The evidence from this study suggests that aromatherapy can be effective in reducing maternal anxiety, fear, and/or pain during labor. The use of aromatherapy appeared to facilitate a further reduction in the use of systemic opioids in the study center, from 6% in 1990 to 0.4% in 1997 (per woman). Aromatherapy is an inexpensive care option. The study reports a minimal incidence of associated symptoms. Out of 8058 mothers, 1%100 recorded an associated symptom, all of which were mild in nature.94

HERBS FOR PAIN RELIEF

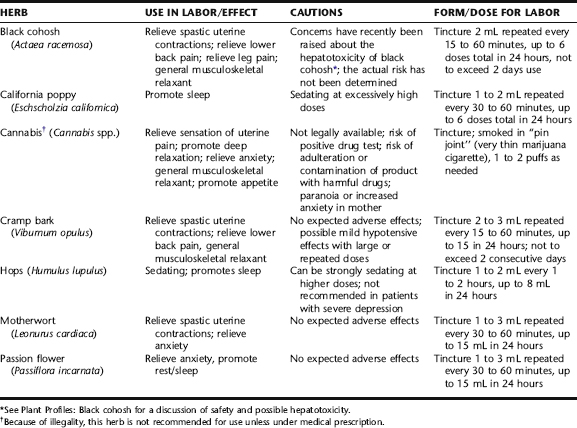

Independent midwives commonly use herbs for pain relief in labor when other, nonpharmacologic methods have not produced adequate results and the mother appears to be suffering. Although the analgesic and sedative actions of herbs are not as quick-acting or powerful as pharmaceuticals, their actions can be gently effective, most with minimal risk of serious side effects, and their use does not preclude subsequent administration of pharmaceutical intervention should it eventually be required. It is not usually expected that herbal medicines will entirely relieve the pain associated with labor, rather they are used to “take the edge off,” promote sleep when needed, and relax incoordinate uterine contractions that may be leading to ineffective and thereby unnecessarily painful labor. The herbs discussed in the following are those that are purely analgesic or sedating in action, and that are most commonly used by midwives for labor pain. These herbs are typically combined into formulae and given repeatedly over a short period of time (e.g., every 15 minutes for 1 hour until desired effect, i.e., sleep, pain relief, is achieved) and repeated as necessary. Maximum daily doses are provided in Table 16-3.

STERILE WATER INJECTIONS

Intracutaneous sterile water (ISW) injections made adjacent to the posterior superior iliac spines are believed to cause distention of the skin, which leads to stimulation of nociceptors and mechanoreceptors, creating a localized sensation that may act as a counterirritation to uterine contraction pain (see Fig. 17-4). A randomized controlled trial (n = 134) was conducted comparing the effectiveness of three nonpharmacologic approaches for relief of back pain: (1) intracutaneous sterile water injections (ISW); (2) transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS); and (3) standard care, including back massage, whirlpool bath, and liberal mobilization. Women self-evaluated both intensity and affective dimensions of pain using visual analog scales. Their evaluations of control and satisfaction were assessed using adapted versions of the Labor Agentry Scale and the Labor and Delivery Satisfaction Index. The results indicated that women in the ISW group rated the intensity and unpleasantness of pain during the experimental period significantly lower than women in the standard care group or the TENS group. Mean pain intensity at 15 and 60 minutes after randomization was significantly reduced in the ISW group compared with the two other groups.95

In another study, 45 pregnant women in the first stage of labor presenting with lower back pain were randomized into two groups. One group received intracutaneous injections of sterile water in the lumbosacral region, whereas the other group was given corresponding subcutaneous injections of isotonic saline, regarded as a placebo treatment. In the group that received intracutaneous sterile water injections the mean pain score was significantly more reduced compared with the placebo group at 10, 45, and 90 minutes after the treatment. The midwives’ blind estimation of the effectiveness of treatment was consistent with the subjective patient assessment. However, the requirement of meperidine was similar in the two groups. The analgesic method presented was found to be an effective treatment against lower back pain during the first stage of labor.96

BIOFEEDBACK

Biofeedback is a noninvasive system that utilizes monitoring instruments to provide visual or auditory feedback to patients based on physiologic responses of which they are usually unaware, for example, pulse or respiratory rate, allowing the patient to gain a sense of self-reliance in their ability to alter these parameters. In a study of 55 first-time mothers randomly assigned to either childbirth classes or childbirth classes plus biofeedback training, women who used biofeedback during labor reported significantly lower pain than women in the control group. Seventy percent of women in the control group requested epidural anesthesia, vs. only 40% in the biofeedback group.97

ACUPUNCTURE

Although the mechanisms of action remain unknown, findings from three randomized controlled trials (Western-based) have concluded that acupuncture during labor can reduce the use of pain medication in labor.98 Numerous trials have been done in China with similar conclusions; however, the quality of these trials has not always met standards for inclusion in meta-analyses. According to the results of a systematic review by Lee and Ernst, three RCTs were identified, and their methodologic quality was generally good. Two RCTs compared adjunctive acupuncture with usual care only and reported a reduction of meperidine and/or epidural analgesia. One placebo acupuncture controlled trial showed a statistically significant difference in both subjective and objective outcome measures of pain. No adverse events were reported in any of the trials. The reviews concluded that the evidence for acupuncture as an adjunct to conventional pain control during labor is promising; however, they commented on the paucity of research upon which to assert a definitive conclusions.99 Whether acupuncture in combination with other forms of nonpharmacologic support, for example, continuous labor support, massage, positional changes, and so forth, would be more effective than acupuncture used alone has not been evaluated.

HYPNOSIS

Two studies on the effects of hypnosis on pain in labor were identified. In one study, 82 first-time low-risk mothers were randomized to attend routine weekly prenatal classes plus individual hypnosis sessions focusing on relaxation and pain relief, or prenatal classes alone. Based on a linear analog scale, no significant difference in subjective reporting of pain relief was reported between the groups and there was no difference in rate of pharmacologic pain medication used in labor.100 In a 1975 study, 60 primiparous women were randomly assigned to either hypnosis induction classes or relaxation and breathing exercise during childbirth classes. Ischemic pain thresholds were measured prior to labor and during labor with a standardized pain questionnaire. Women in the hypnosis group received less pain medication in labor than the control group.97 Hypnotherapy is not widely used by midwives unless women have specific deep-seated fears about labor or past experiences that block effective preparation.