Kyphoscoliosis

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

• List the anatomic alterations of the lungs associated with kyphoscoliosis.

• Describe the causes of kyphoscoliosis.

• List the cardiopulmonary clinical manifestations associated with kyphoscoliosis.

• Describe the general management of kyphoscoliosis.

• Describe the clinical strategies and rationales of the SOAPs presented in the case study.

• Define key terms and complete self-assessment questions at the end of the chapter and on Evolve.

Anatomic Alterations of the Lungs

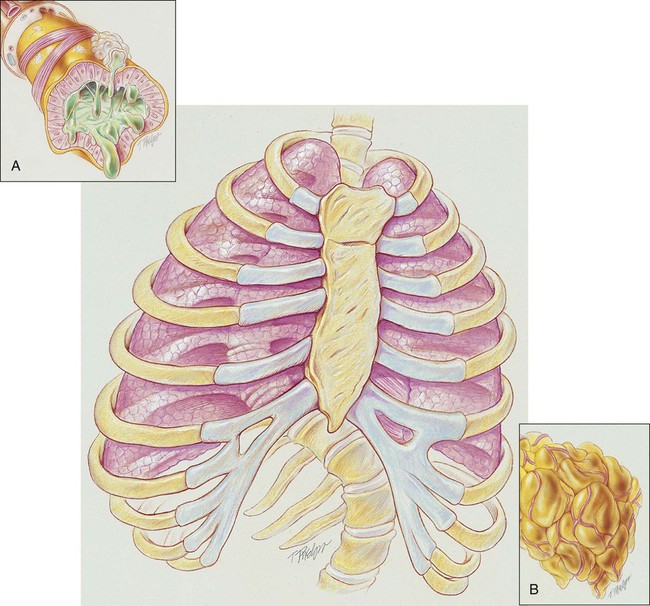

In severe kyphoscoliosis the deformity of the thorax compresses the lungs and restricts alveolar expansion, which in turn causes alveolar hypoventilation and atelectasis. In addition, the patient’s ability to cough and mobilize secretions also may be impaired, further causing atelectasis as secretions accumulate throughout the tracheobronchial tree. Because kyphoscoliosis involves both a posterior and a lateral curvature of the spine, the thoracic contents generally twist in such a way as to cause a mediastinal shift in the same direction as the lateral curvature of the spine. Severe kyphoscoliosis causes a chronic restrictive lung disorder that makes it more difficult to clear airway secretions. Figure 24-1 illustrates the lung and chest wall abnormalities in a typical case of kyphoscoliosis.

Etiology and Epidemiology

• Sex—Girls are more likely to develop curvature of the spine than boys.

• Age—The younger the child is when the diagnosis is first made, the greater the chance of curve progression.

• Angle of the curve—The greater the curvature of the spine, the greater the risk that the curve progression will worsen.

• Location—Curves in the middle to lower spine are less likely to progress than those in the upper spine.

• Height—Taller people have a greater chance of curve progression.

• Spinal problems at birth—Children with scoliosis at birth (congenital scoliosis) have a greater risk for worsening of the curve.

Diagnosis

• Shape (nonstructural scoliosis and structural scoliosis)—A nonstructural scoliosis is a curve that develops side-to-side as a C– or S-shaped curve. This form of scoliosis results from a cause other than the spine itself (e.g., poor posture, leg length discrepancy, pain). A structural scoliosis is a curvature of the spine associated with vertebral rotation. A structural scoliosis involves the twisting of the spine and appears in three dimensions.

• Location—The curve of the spine may develop in the upper back area where the ribs are located (thoracic), the lower back area (lumbar), or in both areas (thoracolumbar).

• Direction—Scoliosis can bend the spine left or right.

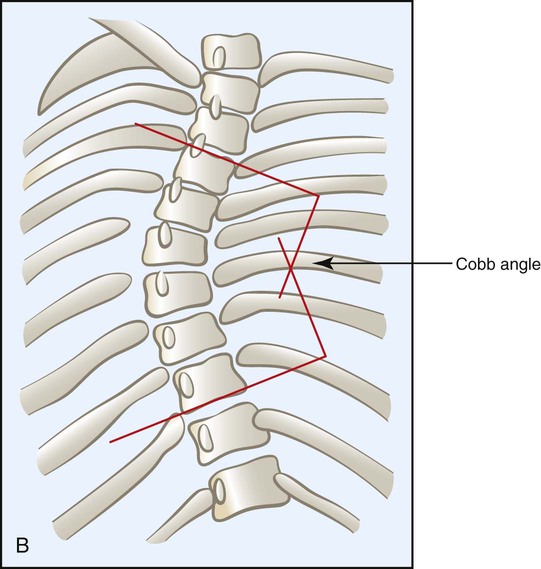

• Angle—A normal spine viewed from the back is zero degrees—a straight line. Scoliosis is defined as a spinal curvature of greater than 10 degrees (i.e., bending toward the ground when in the upright position). The degree of the lateral curvature is expressed by the Cobb angle, which is calculated from a radiograph as shown in Figure 24-2.

General Management of Scoliosis

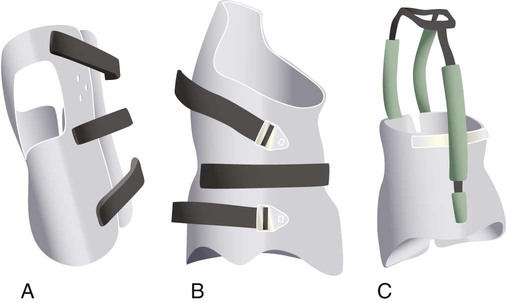

Braces

A brace device is usually recommended as the first line of defense for growing children who have a spinal curvature of 25 to 45 degrees. The mechanical objective of the brace is to hyperextend the spine and to limit forward flexion. It does not reverse the curve. Although a brace does not cure scoliosis (or even improve the condition), it has been shown to prevent the curve progression in more than 90% of patients who wear it. Bracing is not effective in congenital or neuromuscular scoliosis. The therapeutic effects of bracing are also less helpful in infantile and juvenile idiopathic scoliosis. Today a number of braces are available, including the Boston brace, Charleston bending brace, and Milwaukee brace (Figure 24-4). The type of brace is selected according to a the patient’s age, the specific characteristics of the curve, and the willingness of the patient to tolerate a specific brace.

Surgery

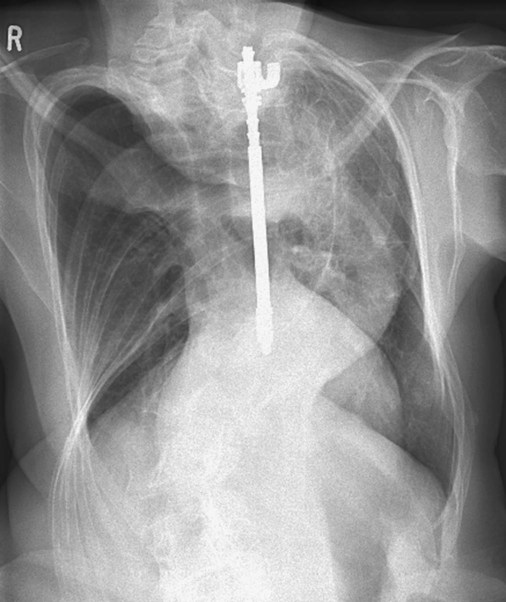

Rod Instrumentation

Rod instrumentation involves the insertion of metal rods (e.g., Harrington rod), hooks, screws, and wires to prevent the curve from moving for 3 to 12 months and to allow the fusion to become solid (Figure 24-5). The system provides disruption to the concave side of the spine and compression to the convex side. This action enhances stabilization, reduces any rotational tendency, and applies force to the spine to correct the curvature. Up to 50% improvement of the curvature may occur in patients who elect to have this procedure.

Respiratory Care Treatment Protocols

Oxygen Therapy Protocol

Oxygen therapy is used to treat hypoxemia, decrease the work of breathing, and decrease myocardial work. The hypoxemia that develops in kyphoscoliosis is commonly caused by atelectasis and pulmonary shunting. Hypoxemia caused by capillary shunting is often refractory to oxygen therapy. In addition, when the patient demonstrates chronic ventilatory failure during the advanced stages of kyphoscoliosis, caution must be taken not to overoxygenate the patient (see Oxygen Therapy Protocol, Protocol 9-1).

CASE STUDY

Kyphoscoliosis

Admitting History

Respiratory Assessment and Plan

S “I’m having trouble breathing.”

O Well-nourished appearance; severe anterior and left lateral curvature of the spine; cyanosis, digital clubbing, and distended neck veins—especially on the right side; cough: frequent, adequate, and productive of moderate amounts of thick yellow sputum; 2+ pitting edema below both knees; vital signs: BP 160/100, HR 90, RR 18, T 36.3° C (97.4° F); trachea deviated to the right; both lungs: dull percussion notes, crackles, and rhonchi; PFT: VC, FRC, and RV 45% to 50% of predicted; Hct 58%, Hb 18 g%; CXR: severe thoracic and spinous deformity, mediastinal shift, cardiomegaly, and bilateral infiltrates in the lung bases consistent with pneumonia or atelectasis; ABGs (room air): pH 7.52, Paco2 58,  46, Pao2 49; Spo2 88%

46, Pao2 49; Spo2 88%

• Severe kyphoscoliosis (history, CXR, physical examination)

• Increased work of breathing (elevated blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate)

• Excessive bronchial secretions (sputum, rhonchi)

• Infection likely (thick, yellow sputum)

• Good ability to mobilize secretions (strong cough)

• Atelectasis and consolidation (CXR)

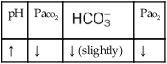

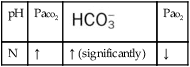

• Acute alveolar hyperventilation superimposed on chronic ventilatory failure with moderate hypoxemia (ABGs)

P Initiate Oxygen Therapy Protocol (HAFOE at Fio2 0.28; be careful not to overoxygenate the patient). Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol (obtain sputum for culture; C&DB instructions and oral suction prn). Lung Expansion Therapy Protocol (incentive spirometry qid and prn). Aerosolized Medication Protocol (aerosolized Xopenex 0.5 mL in 1.5 mL 10% acetylcysteine q4h). Notify physician of admitting ABGs and impending ventilatory failure. Place mechanical ventilator on standby. Monitor closely.

10 Hours after Admission

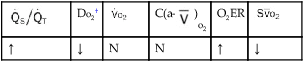

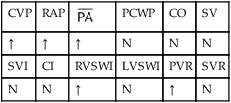

Several of the patient’s hemodynamic indices were elevated: CVP, RAP, PA, RVSWI, and PVR.* Her oxygenation indices were as follows: increased  and O2ER and decreased Do2 and

and O2ER and decreased Do2 and  . Her

. Her  and

and  were normal.† No recent chest x-ray film was available. Her ABGs on an Fio2 of 0.28 were as follows: pH 7.57, Paco2 49,

were normal.† No recent chest x-ray film was available. Her ABGs on an Fio2 of 0.28 were as follows: pH 7.57, Paco2 49,  44, and Pao2 43. Her Spo2 was 87%. On the basis of these clinical data, the following SOAP was documented.

44, and Pao2 43. Her Spo2 was 87%. On the basis of these clinical data, the following SOAP was documented.

Respiratory Assessment and Plan

S Severe dyspnea; “I’m extremely short of breath.”

O Extreme respiratory distress; cyanosis and perspiration; distended neck veins; weak, spontaneous cough; sounds of congestion but no sputum produced; bilateral dull percussion notes, crackles, and rhonchi; vital signs: BP 180/120, HR 130, RR 26, T 37.8° C (100° F); hemodynamics: increased CVP, RAP, PA, RVSWI, and PVR; oxygenation indices: increased  , and O2ER and decreased Do2 and

, and O2ER and decreased Do2 and  ;

;  and

and  normal; ABGs; pH 7.57, Paco2 49,

normal; ABGs; pH 7.57, Paco2 49,  44, Pao2 43; Spo2 87%

44, Pao2 43; Spo2 87%

• Severe kyphoscoliosis (history, physical exam, CXR)

• Increased work of breathing, worsening (increased blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate)

• Excessive bronchial secretions (rhonchi, congested cough)

• Atelectasis and consolidation (previous CXR)

• Acute alveolar hyperventilation superimposed on chronic ventilatory failure with moderate-to-severe hypoxemia (ABGs and history)

• Impending ventilatory failure

• Continued critically ill status, but chances of avoiding ventilatory failure improving

P Up-regulate Oxygen Therapy Protocol (HAFOE at 0.35). Up-regulate Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol (add CPT and PD qid). Up-regulate Aerosolized Medication Protocol (increase med. nebs. to q2h). Contact physician regarding possible ventilatory failure. Discuss therapeutic bronchoscopy with physician. Continue to keep mechanical ventilator on standby. Monitor and reevaluate in 30 minutes.

Respiratory Assessment and Plan

S “I feel so much better. I finally have enough wind to eat some food.”

O Cyanotic appearance; cough: strong, small amount of white sputum; vital signs: BP 140/85, HR 83, RR 14, T normal; crackles, rhonchi, and dull percussion notes over both lung fields; rhonchi improving; hemodynamic and oxygenation indices improving, but still an elevated CVP, RAP, PA, RVSWI, and PVR and still an increased  and O2ER and a decreased Do2 and

and O2ER and a decreased Do2 and  ; CXR: improvement of the bilateral pneumonia and atelectasis; ABGs: pH 7.45, Paco2 73,

; CXR: improvement of the bilateral pneumonia and atelectasis; ABGs: pH 7.45, Paco2 73,  49, Pao2 68; Spo2 94%

49, Pao2 68; Spo2 94%

• Generally improved respiratory status (history, CXR, hemodynamic and oxygenation indices, ABGs)

• Significant improvement in problem with excessive bronchial secretions (rhonchi, cough)

• Improvement in atelectasis and consolidation (CXR)

• Chronic ventilatory failure with mild hypoxemia (ABGs)

• Current ABGs are likely close to patient’s normal (baseline) ABGs

P Down-regulate Oxygen Therapy Protocol, Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol, and Aerosolized Medication Protocols. Continue to monitor and reevaluate (ABGs on reduced Fio2). Recommend pulmonary rehabilitation and patient and family education (cuirass respiratory ventilation, possibly rocking bed, BIPAP, or positive expiratory pressure [PEP]).

Discussion

At the time of the second assessment, the intensity of the patient’s respiratory distress was increasing. This was verified by the continued observation of the high pulse and respiratory rate, excessive bronchial secretions, dull percussion notes, acute alveolar hyperventilation on top of chronic ventilatory failure with moderate to severe hypoxemia, atelectasis on the chest x-ray film, and poor response to oxygen therapy. Undoubtedly, impending ventilatory failure was more likely. Atelectasis is often refractory to oxygen therapy, suggesting that therapeutic bronchoscopy might have been worthwhile. At that point in time, the up-regulation of the Oxygen Therapy Protocol (Protocol 9-1), Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol (Protocol 9-2), and Aerosolized Medication Protocol (Protocol 9-4) were all justified by the clinical indicators.

*CVP, Central venous pressure; PA, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RAP, right atrial pressure; RVSWI, right ventricular stroke work index.

† , Arterial-venous oxygen difference; Do2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;

, Arterial-venous oxygen difference; Do2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;  , pulmonary shunt fraction;

, pulmonary shunt fraction;  , mixed venous oxygen saturation;

, mixed venous oxygen saturation;  , oxygen consumption.

, oxygen consumption.

)

)

)O2, Arterial-venous oxygen difference; DO2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;

)O2, Arterial-venous oxygen difference; DO2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;  , pulmonary shunt fraction;

, pulmonary shunt fraction;  , mixed venous oxygen saturation;

, mixed venous oxygen saturation;  , oxygen consumption.

, oxygen consumption.

, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RAP, right atrial pressure; RVSWI, right ventricular stroke work index; SV, stroke volume; SVI, stroke volume index; SVR, systemic vascular resistance.

, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RAP, right atrial pressure; RVSWI, right ventricular stroke work index; SV, stroke volume; SVI, stroke volume index; SVR, systemic vascular resistance.

46, and Pa

46, and Pa and O2ER and a decreased D

and O2ER and a decreased D . Her

. Her  and

and  were normal. The patient’s chest x-ray film, taken earlier that morning, showed some clearing of the pneumonia and atelectasis described on admission. Her ABGs on an F

were normal. The patient’s chest x-ray film, taken earlier that morning, showed some clearing of the pneumonia and atelectasis described on admission. Her ABGs on an F 49, and Pa

49, and Pa