18 Kidneys and urinary tract

Symptoms of renal and urological disease

Haematuria

Haematuria arising from renal tumours is likely to be:

It is important to decide early in the diagnostic process whether the haematuria originates from the kidneys or elsewhere in the urinary tract (Box 18.1). This decision affects the order in which investigations should be conducted. For example, continuous painless microscopic haematuria with associated proteinuria in a young man or woman is most likely to be the result of glomerulonephritis or other renal pathology. However, haematuria in an older person with risk factors for urothelial malignancy (smoking) is more likely to be caused by a bladder or ureteric tumour and merits a cystoscopy early in the investigative process. It is important to remember that the commonest cause of dipstick haematuria in women is contamination from menstrual blood.

Physical signs in renal and urological disease

These physical signs fall into three principal groups:

1 Local signs related to the specific pathology, for example an enlarged palpable tender kidney in renal carcinoma, or a palpably enlarged bladder in a patient with acute or chronic retention.

2 Symptoms of disturbance of renal salt and water handling, with resulting clinical evidence of extracellular fluid volume expansion or contraction.

3 Signs of failure of the kidney’s normal excretory and metabolic functions.

General features

Patients with chronic renal failure look unwell. The skin is pallid, the complexion sallow and a slightly yellowish hue is often evident. The mucous membranes are pale, reflecting the associated normochromic, normocytic anaemia. There may be bruises, purpura and scratch marks due to uraemic pruritus, and also an underlying disorder of platelet function and capillary fragility. The nails often appear pale and opaque (leukonychia) in the nephrotic syndrome, and sometimes in chronic renal failure. Intercurrent episodes of severe illness in the past may have led to the appearance of Beau’s lines, which appear as transverse ridges across the nails. Splinter haemorrhages in the nail beds point to underlying vasculitis, which may be the cause of the renal failure or be indicative of endocarditis; there may be an associated purpuric rash (Fig. 18.1). When blood urea is very high, a uraemic frost may be seen on any part of the body and appears as a white powder; it is formed from crystalline urea deposited on the skin via the sweat. The onset of chronic renal failure in childhood is associated with impaired growth, causing short stature. Severe bony deformity may be evident in some cases, particularly in children, who may develop rickets (Fig. 18.2). Advanced uraemia is also associated with metabolic flap, a coarse tremor which is best seen at the wrists when in the dorsiflexed position. It is similar to the metabolic flap (asterixis) seen in patients with advanced liver disease or respiratory failure. The presence of metabolic acidosis leads to increased ventilation with an increased tidal volume, known as Kussmaul respiration.

The circulation in the renal patient

Hypervolaemia is associated with some or all of the following:

Elevation of the jugular venous pressure.

Elevation of the jugular venous pressure.

Peripheral oedema at the ankles or sacrum.

Peripheral oedema at the ankles or sacrum.

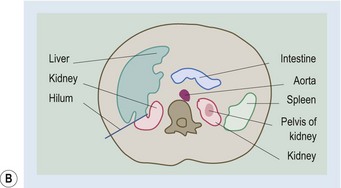

Abdominal palpation

The detection of the kidneys in the abdominal examination is described in Chapter 12. In slim people with relaxed abdominal muscles, it is sometimes possible to feel a normal right kidney (the right kidney is situated slightly lower than the left at the level of T12-L3). More often a palpable kidney can only be felt because it is enlarged, as in hydronephrosis, multiple cysts (polycystic kidney disease) or tumour (generally unilateral). A distended bladder is identified in the lower abdomen by a combination of palpation and percussion. Rectal examination is an important part of the clinical assessment of the renal patient: bimanual palpation of the bladder is a more reliable way of assessing bladder enlargement than is simple per abdominal examination. In men, rectal examination also allows evaluation of the prostate gland, both for benign enlargement and for the detection of malignant change suggested by hard irregularity of the gland and absence of the central groove.

The eye in uraemia

Corneal calcification (limbic calcification) occurs in patients with longstanding hyperparathyroidism with elevation of blood calcium and phosphorus concentrations (see Ch. 16). The presence of limbic calcification should not be confused with a corneal arcus (arcus senilis), which is a broader band at the edge of the cornea and merges with the sclera. Corneal arcus is usually most marked in the superior and inferior positions, whereas limbic calcification is seen medially and laterally or circumferentially. Retinal changes are extremely important in uraemic patients, many of whom have hypertension and/or diabetes. Renal dysfunction in the absence of diabetic retinopathy cannot be attributed to diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 1 diabetes. In type 2 diabetes, however, diabetic nephropathy is present in many patients without any diabetic eye changes. Patients with renal disease as part of systemic vasculitis may have manifestations of the latter in the retinae, with haemorrhages and exudates. Patients with chronic renal failure are at greatly increased risk of a range of vascular complications affecting both the macrovasculature and the microvasculature. In the retinae, thrombosis of the central retinal artery or its branches, or of the central retinal vein and its branches, is an important manifestation of this. The presence of Kayser-Fleischer rings may help confirm a diagnosis of Wilson’s disease.

The renal and urological syndromes

These syndromes are listed in Table 18.1. Some are exclusively renal, others exclusively urological, and some fall into both areas. The effects of renal failure on other organ systems are listed in Box 18.2.

| Renal | Renal and urological | Urological |

|---|---|---|

Box 18.2 Effects of renal failure on other organ systems

The acute nephritic syndrome

As in acute renal failure, the acute nephritic syndrome implies a fairly brisk onset (days, weeks or months) of reduction in GFR and retention of nitrogenous waste, and usually salt and water also. Oliguria is, therefore, common. The underlying pathology is an acute glomerulonephritis which, as well as causing the functional abnormalities described above, also results in florid abnormalities of the urine. Haematuria (macroscopic or microscopic), proteinuria and tubular casts are often present. Many of the causes of acute nephritis are associated with functional abnormalities of the immune system which may be detected by laboratory tests and which may also manifest with disease in other organs, for example the skin, joints or eyes, as in SLE, Henoch-Schönlein purpura (see Fig. 18.1) and systemic vasculitis.

Laboratory assessment and imaging of the kidneys and urinary tract: assessment of structure and function

The urine

Specific gravity and osmolality

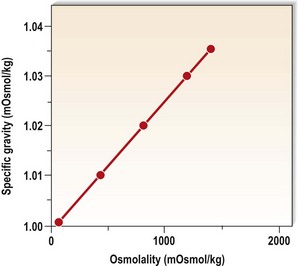

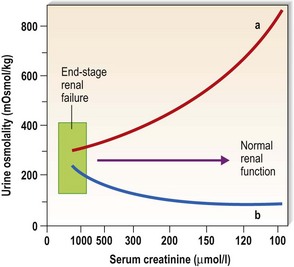

These measurements yield similar information and, in the absence of significant glycosuria, are functions of the urinary concentrations of sodium, chloride and urea. The range of specific gravity is 1.001-1.035, which is equivalent to 50-1350 mOsmol/kg water (Fig. 18.3). The presence of renal insufficiency leads to a reduction in the range of osmolality that the kidneys can generate and, in advanced renal disease, the osmolality becomes relatively fixed at about 300 mOsmol/kg water, close to that of the glomerular filtrate (Fig. 18.4). This is termed isosthenuria, and because the urine concentration cannot be varied, predisposes the patient to sodium and water overload if intake is high, and to salt and water depletion if intake is low.

Protein

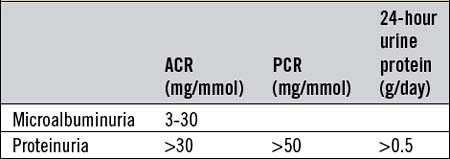

The normal daily urine protein output is <150 mg. Dipsticks reactive to urine albumin provide a simple semiquantitative test. They are sensitive to 200-300 mg protein/l and have almost completely superseded the more cumbersome sulphosalicylic acid test. The urinary protein excretion rate generally rises in the upright posture and with activity and, in some normal individuals, this may lead to apparently abnormal proteinuria on spot urine specimens in ambulant patients, and even in 24-hour urine collections (orthostatic proteinuria). Measurement of protein in an early-morning urine, however, reveals no protein, and this serves to distinguish abnormal proteinuria from orthostatic proteinuria. A further refinement is the specific measurement of urine albumin, which is increasingly used and should be <20 mg/day. Albumin excretion in the range 20-200 mg/day is termed microalbuminuria. Although this range is frequently too low to be detectable by stick testing, it is an important finding, particularly in diabetics in whom it predicts the later onset of overt diabetic nephropathy. The albumin : creatinine (ACR) and protein : creatinine (PCR) ratios are useful surrogate markers for proteinuria and are increasingly used instead of the 24-hour urine collection for quantification of protein excretion (Table 18.2).

The diagnostic implications of proteinuria depend greatly on its magnitude (Table 18.3). Heavy proteinuria (>1.5 g/day) is nearly always glomerular in origin and albumin predominates over larger proteins such as globulins. Other proteins, rarely measured, arise from the renal tubules and include Tamm-Horsfall protein, retinol-binding protein and nephrocalcin, the latter helping to prevent the formation of urinary stones. It is worth noting that urine light chains may not be detected by some routine laboratory urine protein assays and have to be sought separately.

| Mild (<500 mg/day) | Moderate (up to 3 g/day) | Heavy (>3 g/day) |

|---|---|---|

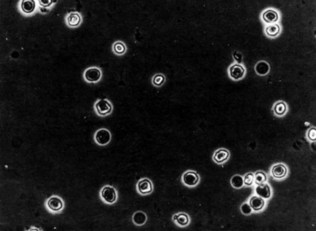

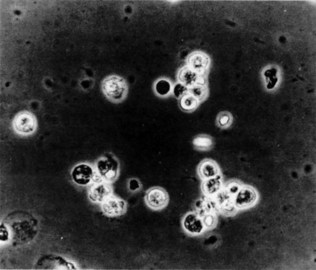

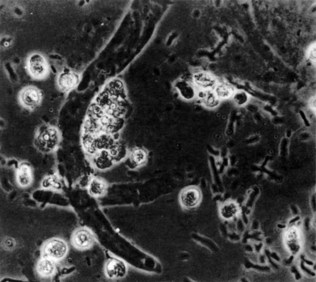

Microscopy

(See Figs 18.5–18.8.) This is performed after slow spinning (at not more than 1000 g) of a fresh urine specimen for approximately 2 minutes. The pellet is resuspended in 0.5 ml of urine and examined unstained on a microscope slide under a coverslip. Important findings include leukocytes (suggestive of infection), red blood cells and various types of tubular casts. The presence of tubular casts is indicative of parenchymal renal disease. They may be red cell casts or white cell casts, in which Tamm-Horsfall protein matrix has solidified and is studded with red or white blood cells. Granular casts probably represent degenerate cellular casts and have a grainy appearance. Hyaline casts contain no elements or debris and may be seen in small numbers in normal urine. It is usual to express the number of cells or casts seen per high-power field. The presence of red cell casts should alert one to the possibility of an aggressive glomerulonephritis. Red cell morphology may be a useful indicator as to the source of bleeding. Red cells with a normal outline usually, but not always, arise from the renal collecting system or from a point downstream of that, whereas red cells arising from the glomeruli are often distorted, probably as a result of movement through the glomeruli or osmotic insults during passage down the renal tubule.

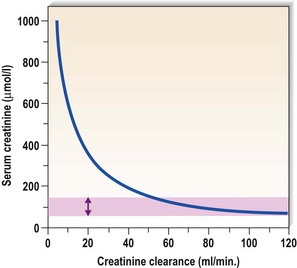

Measurement of the glomerular filtration rate

Accurate assessment of the GFR requires measurement in blood alone or blood and urine of a compound that is filtered freely at the glomerulus and neither reabsorbed nor secreted by the tubules (Table 18.4). Inulin is the best agent, but involves a continuous infusion of inulin and measurements of inulin concentration in plasma and urine. This is a laborious investigation that is generally confined to research, and is not routinely available. A number of surrogates for the inulin clearance method exist, however, and details of these are given in Table 18.4. The most frequently used surrogates, and also the crudest ones, are the plasma urea and plasma creatinine concentrations. Both compounds are produced endogenously (at an inconstant rate in the case of urea) and excreted by glomerular filtration. Neither is particularly accurate when used to establish the absolute level of glomerular filtration in an individual patient, although the plasma creatinine concentration is certainly very useful when used to follow changes in an individual patient’s renal function, especially when the GFR is significantly reduced (Fig. 18.9). Creatinine clearance is more precise, but requires a 24-hour urine collection with measurements of plasma creatinine concentration and urine creatinine excretion rate. The clearance is then calculated using the simple formula UV/P where U equals the urinary concentration of creatinine, V the urinary flow rate (usually expressed in ml/min) and P equals the plasma creatinine concentration. This formula can be applied to urea or to any other compound subject to renal excretion. Only those compounds that are freely filtered at the glomerulus and neither secreted nor reabsorbed by the renal tubules are suitable for GFR measurement.

| Method | Comments |

|---|---|

| Plasma urea |

The use of mathematical formulae to estimate GFR has been gaining in popularity, as most of these calculations require simple information such as the age, sex, weight and serum creatinine to derive an estimated GFR (Table 18.5). Precise measures of GFR used in clinical practice depend on measurement of the excretion of certain administered compounds. The most commonly used is 51Cr-EDTA, which gives a relatively easy and reproducible measure of GFR. It should be remembered that the GFR peaks at 20-25 years of age and at about 120 ml/min, and declines steadily thereafter at a rate of approximately 1 ml/min/year. Appreciation of this age-related change in GFR is important in clinical practice, particularly when prescribing drugs to the elderly.

Table 18.5 Estimation of GFR formulae

| Cockcroft and Gault | Male GFR = [1.23 × weight (kg) × (140 − age)]/creatinine |

| Female GFR = [1.03 × weight (kg) × (140 − age)]/creatinine | |

| Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) | GFR = 186 × Pcr − 1.154 × age − 0.203 × 1.212 (if black) × 0.742 (if female) |

Pcr, plasma creatinine in mg/dl.

Measurement of renal tubular function

Assessment of the urine in the stone-forming patient

Kidney biopsy

Imaging of the urinary tract

Intravenous urography

Intravenous urography (IVU) involves the intravenous injection of organic iodine compounds that are excreted and concentrated radiographically. It is an extremely good technique for examining the renal collecting system, the ureters and the bladder, but gives less information than ultrasound about the renal parenchyma (Fig. 18.10). Imaging by IVU depends on renal function. This is useful in that it gives a crude measure of the symmetry or otherwise of excretory capacity, but it also means that the image quality is poor in patients with renal insufficiency in whom the GFR is low (Fig. 18.11).

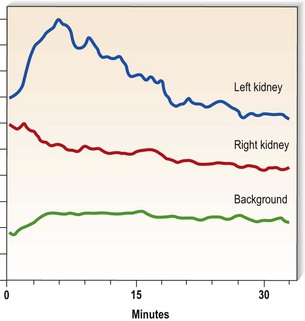

Radionuclide studies

Diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid (99Tc-DTPA) is used to investigate the excretory function of each kidney selectively (Fig. 18.12). The test is very useful for the assessment of symmetry of function, delayed onset of excretion (as may happen in renal artery stenosis) and retention of excreted isotope (as seen in the presence of obstruction). 99Tc-DMSA (dimercaptosuccinic acid) is a similar technique used to show the gross renal morphology.

Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging

Computed tomography scanning of the kidneys sometimes complements the information gained from ultrasound and certainly yields important information about the surrounding structures in the retroperitoneum (Fig. 18.13). It is particularly useful in patients with ureteric obstruction from, for example, retroperitoneal malignancy or retroperitoneal fibrosis. Spiral CT is becoming the investigation of choice for renal calculi as well. In some cases, more information is obtained using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Caution has to be exercised, however, if gadolinium is required, as its use has been associated with nephrogenic systemic fibrosis in patients with renal disease. Current data suggest an increased risk of this condition in patients with a GFR below 30 ml/min.