Chapter 160 Kawasaki Disease

Clinical Manifestations

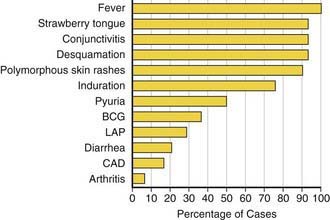

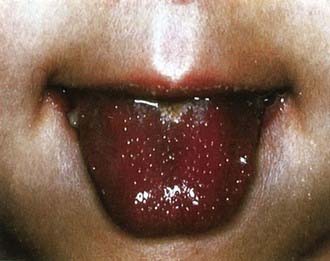

Fever is characteristically high (≥101°F), unremitting, and unresponsive to antibiotics. The duration of fever without treatment is generally 1-2 wk but may persist for 3-4 wk. In addition to fever, the five principal clinical criteria of KD are: bilateral nonexudative bulbar conjunctival injection with limbal sparing; erythema of the oral and pharyngeal mucosa with strawberry tongue and dry, cracked lips; edema and erythema of the hands and feet; rash of various forms (maculopapular, erythema multiforme, or scarlatiniform) with accentuation in the groin area; and nonsuppurative cervical lymphadenopathy, usually unilateral, with node size >1.5 cm (Table 160-1; Figs. 160-1 to 160-4). Perineal desquamation is common in the acute phase. Periungual desquamation of the fingers and toes begins 1-3 wk after the onset of illness and may progress to involve the entire hand and foot (Fig. 160-5).

Table 160-1 CLINICAL AND LABORATORY FEATURES OF KAWASAKI DISEASE

EPIDEMIOLOGIC CASE DEFINITION (CLASSIC CLINICAL CRITERIA)*

OTHER CLINICAL AND LABORATORY FINDINGS

LABORATORY FINDINGS IN ACUTE KAWASAKI DISEASE

* Patients with fever at least 5 days and <4 principal criteria can be diagnosed with Kawasaki disease when coronary artery abnormalities are detected by two-dimensional echocardiography or angiography.

† In the presence of ≥4 principal criteria, Kawasaki disease diagnosis can be made on day 4 of illness. Experienced clinicians who have treated many patients with Kawasaki disease may establish diagnosis before day 4.

‡ See differential diagnosis (Table 160-2).

§ Some infants present with thrombocytopenia and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

From Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Gerber MA, et al: Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease, Pediatrics 114:1708–1733, 2004.

Figure 160-2 Strawberry tongue in mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome (Kawasaki disease).

(Courtesy of Tomisaku Kawasaki, MD.) (From Hurwitz S: Clinical pediatric dermatology, ed 2, Philadelphia, 1993, WB Saunders.)

Figure 160-3 Congestion of bulbar conjunctiva in a patient with mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome (Kawasaki disease).

(Courtesy of Tomisaku Kawasaki, MD.) (From Hurwitz S: Clinical pediatric dermatology, ed 2, Philadelphia, 1993, WB Saunders.)

Figure 160-4 Indurative edema of the hands in mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome (Kawasaki disease).

(Courtesy of Tomisaku Kawasaki, MD.) (From Hurwitz S: Clinical pediatric dermatology, ed 2, Philadelphia, 1993, WB Saunders.)

Figure 160-5 Desquamation of the fingers in a patient with mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome (Kawasaki disease).

(Courtesy of Tomisaku Kawasaki, MD.) (From Hurwitz S: Clinical pediatric dermatology, ed 2, Philadelphia, 1993, WB Saunders.)

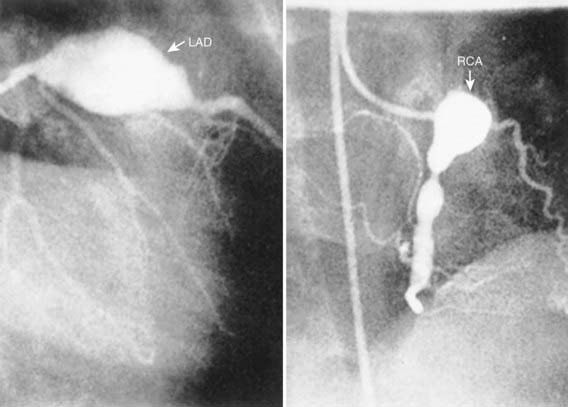

Cardiac involvement is the most important manifestation of KD. Myocarditis occurs in most patients with acute KD and manifests as tachycardia out of proportion to fever along with diminished left ventricular systolic function. Occasionally, patients with KD present in shock, with markedly diminished left ventricular function. Pericarditis with a small pericardial effusion can also occur during the acute illness. Mitral regurgitation of at least mild severity is evident on echocardiography in approximately one quarter of patients at presentation but diminishes over time, except among rare patients with coronary aneurysms and ischemic heart disease. Coronary artery aneurysms develop in up to 25% of untreated patients in the second to third week of illness and are best detected by two-dimensional echocardiography. Giant coronary artery aneurysms (≥8 mm internal diameter) pose the greatest risk for rupture, thrombosis or stenosis, and myocardial infarction (Fig. 160-6). Axillary, popliteal, iliac, or other arteries may also be involved by aneurysm, which manifests as a localized pulsating mass.

Diagnosis

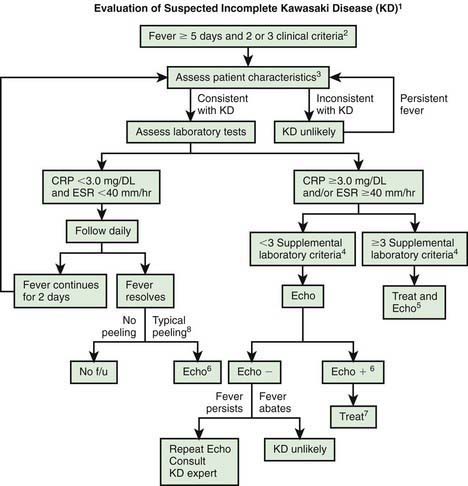

The diagnosis of KD is based on the presence of characteristic clinical signs. For classic KD, the diagnostic criteria require the presence of fever for at least 4 days and at least four of five of the other principal characteristics of the illness (see Table 160-1). In atypical or incomplete KD, patients have persistent fever but fewer than four of the five characteristics. In these patients, laboratory and echocardiographic data can assist in the diagnosis (Fig. 160-7). Incomplete cases are most frequent in infants, who, unfortunately, also have the highest likelihood of development of coronary artery abnormalities. Ambiguous cases should be referred to a center with experience in the diagnosis of KD. Establishing the diagnosis with prompt institution of treatment is essential to prevent potentially devastating coronary artery disease.

Figure 160-7 Algorithm for evaluation of suspected incomplete Kawasaki disease (KD). 1, In the absence of a gold standard for diagnosis, this algorithm cannot be evidence based but rather represents the informed opinion of the expert committee. Consultation with an expert should be sought anytime assistance is needed. 2, Infants ≤6 mo old on day ≥7 of fever or later without other explanation should undergo laboratory testing and, if evidence of systemic inflammation is found, an echocardiogram (Echo), even if they have no clinical criteria. 3, Patient characteristics suggesting KD are listed in Table 160-1. Characteristics suggesting disease other than KD include exudative conjunctivitis, exudative pharyngitis, discrete intraoral lesions, bullous or vesicular rash, and generalized adenopathy. Consider alternative diagnoses (see Table 160-2). 4, Supplemental laboratory criteria include albumin ≤3.0 g/dL, anemia for age, elevation of alanine aminotransferase, platelet count after 7 days ≥450,000/mm3, white blood cell count ≥15,000/mm3, and urine white blood cell count ≥10 /high-power field. 5, Can treat before performing echocardiogram. 6, Echocardiogram findings are considered positive (Echo +) for purposes of this algorithm if any of 3 conditions are met: z score of left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) or right coronary artery (RCA) ≥2.5; coronary arteries meet Japanese Ministry of Health criteria for aneurysms; ≥3 other suggestive features exist, including perivascular brightness, lack of tapering, decreased left ventricle (LV) function, mitral regurgitation, pericardial effusion, or z scores in LAD or RCA of 2-2.5. 7, If echocardiogram findings are positive, treatment should be given to children within 10 days of fever onset and to those beyond day 10 with clinical and laboratory signs (C-reactive protein [CRP], erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR]) of ongoing inflammation. 8, Typical peeling begins under nail beds of fingers and then toes. Echo −, negative echocardiogram findings; f/u, follow-up.

(From Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Gerber MA, et al: Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease, Pediatrics 114:1708–1733, 2004.)

Differential Diagnosis

Adenovirus, measles, and scarlet fever lead the list of common childhood infections that mimic KD (Table 160-2). Children with adenovirus typically have exudative pharyngitis and exudative conjunctivitis, allowing differentiation from KD. A common clinical problem is the differentiation of scarlet fever from KD in a child who is a group A streptococcal carrier. Patients with scarlet fever typically have a rapid clinical response to appropriate antibiotic therapy. Such treatment for 24-48 hr with clinical reassessment generally clarifies the diagnosis. Furthermore, ocular findings are quite rare in group A streptococcal pharyngitis and may assist in the diagnosis of KD. Streptococcal and staphylococcal toxin–mediated illnesses must also be considered, especially the toxic shock syndromes.

Table 160-2 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF KAWASAKI DISEASE

VIRAL INFECTIONS

BACTERIAL INFECTIONS

RHEUMATOLOGIC DISEASE

OTHER

Treatment

Patients with acute KD should be treated with 2 g/kg of intravenous gammaglobulin (IVIG) and high-dose aspirin (80-100 mg/kg/day divided q6h) as soon as possible after diagnosis and, ideally, within 10 days of disease onset (Table 160-3). The mechanism of action of IVIG in KD is unknown, but treatment results in rapid defervescence and resolution of clinical signs of illness in 85-90% of patients. The prevalence of coronary disease, which is 20-25% in children treated with aspirin alone, is only 2-4% in those treated with IVIG and aspirin within the first 10 days of illness. Strong consideration should be given to treating patients with persistent fever who are diagnosed after the 10th day of fever. The dose of aspirin is usually decreased from anti-inflammatory to antithrombotic doses (3-5 mg/kg/day as a single dose) after the patient has been afebrile for 48 hr, although some experts prescribe high-dose aspirin until the 14th day of illness. Aspirin is continued for its antithrombotic effect until 6 to 8 wk after illness onset and is then discontinued in patients who have had normal echocardiography findings throughout the course of their illness. Patients with coronary artery abnormalities continue with aspirin therapy and may require anticoagulation, depending on the degree of coronary dilation (see later).

Table 160-3 TREATMENT OF KAWASAKI DISEASE

ACUTE STAGE

CONVALESCENT STAGE

LONG-TERM THERAPY FOR PATIENTS WITH CORONARY ABNORMALITIES

ACUTE CORONARY THROMBOSIS

Ashouri N, Takahashi M, Dorey F, et al. Risk factors for nonresponse to therapy in Kawaski disease. J Pediatr. 2008;153:365-368.

Baker AL, Lu M, Minich LL, et al. Associated symptoms in the ten days before diagnosis of Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr. 2009;154:592-595.

Broderick L, Tremoulet AH, Burns JC, et al. Recurrent fever syndromes in patients after recovery from Kawasaki syndrome. Pediatrics. 2011;127(2):e489-e493.

Burgner D, Davila S, Breunis WB, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies novel and functionally related susceptibility loci for Kawasaki disease. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000319.

Burns JC, Best BM, Mejias A, et al. Infliximab treatment of intravenous immunoglobulin-resistant Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr. 2008;153:833-838.

Choueiter NF, Olson AK, Shen DD, et al. Prospective open-label trial of etanercept as adjunctive therapy for Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr. 2010;175:960-966.

Gomard-Mennesson E, Landron C, Dauphin C, et al. Kawasaki disease in adults. Medicine. 2010;89(3):149-158.

Gupta-Malhotra M, Gruber D, Abraham SS, et al. Atherosclerosis in survivors of Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr. 2009;155:572-577.

Harnden A, Takahasho M, Burgner D. Kawasaki disease. BMJ. 2009;338:1133-1138.

Hirono K, Kemmotsu Y, Wittkowski H, et al. Infliximab reduces the cytokine-mediated inflammation but does not suppress cellular infiltration of the vessel wall in refractory Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Res. 2009;65:696-701.

Holman RC, Curns AT, Belay ED, et al. Kawasaki syndrome hospitalizations in the United States, 1997 and 2000. Pediatrics. 2003;112:495-501.

Ikemoto Y, Ogino H, Teraguchi M, et al. Evaluation of preclinical atherosclerosis by flow-mediated dilatation of the brachial artery and carotid artery analysis in patients with a history of Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Cardiol. 2005;26:782-786.

Kanegaye JT, Wilder MS, Molkara D, et al. Recognition of a Kawasaki disease shock syndrome. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e783-e789.

Kao AS, Getis A, Brodine S, et al. Spatial and temporal clustering of Kawasaki syndrome cases. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:981-985.

Kitamura S, Tsuda E, Kobayashi J, et al. Twenty-five-year outcome of pediatric coronary artery bypass surgery for Kawasaki disease. Circulation. 2009;120:60-68.

Kobayashi T, Inoue Y, Takeuchi K, et al. Prediction of intravenous immunoglobulin unresponsiveness in patients with Kawasaki disease. Circulation. 2006;113:2606-2612.

Kobayashi T, Inoue Y, Takeuchi K, et al. Risk stratification in the decision to include prednisolone with intravenous immunoglobulin in primary therapy of Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:498-502.

Manlhiot C, Yeung RSM, Clarizia NA, et al. Kawasaki disease at the extremes of the age spectrum. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e410-e415.

McCrindle BW. Kawasaki disease: a childhood disease with important consequences into adulthood. Circulation. 2009;120:6-8.

Muta H, Ishii M. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass grafting for stenotic lesions after Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr. 2010;157:120-126.

Muta H, Ishil M, Iemura M, et al. Health-related quality of life in adolescents and young adults with a history of Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr. 2010;156:439-443.

Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Gerber MA, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a statement for health professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, American Heart Association. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1708-1733.

Newburger JW, Sleeper LA, McCrindle BW, et al. Randomized trial of pulsed corticosteroid therapy for primary treatment of Kawasaki disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:663-675.

Niboshi A, Hamaoka K, Sakata K, et al. Endothelial dysfunction in adult patients with a history of Kawasaki disease. Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167:189-196.

Nomura Y, Arata M, Koriyama C, et al. A severe form of Kawasaki disease presenting with only fever and cervical lymphadenopathy at admission. J Pediatr. 2010;156:786-791.

Rowley AH, Baker SC, Shulman ST, et al. Cytoplasmic inclusion bodies are detected by synthetic antibody in ciliated bronchial epithelium during acute Kawasaki disease. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1757-1766.

Seki M, Kobayashi T, Kobayashi T, et al. External validation of a risk score to predict intravenous immunoglobulin resistance in patients with Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Infect Dis. 2011;30(2):145-147.

Tremoulet AH, Best BM, Song S, et al. Resistance to intravenous immunoglobulin in children with Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr. 2008;153:117-121.

Uehara R, Belay ED, Maddox RA, et al. Analysis of potential risk factors associated with nonresponse to initial intravenous immunoglobulin treatment among Kawasaki disease patients in Japan. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:155-160.