CHAPTER 17 Kapandji Pinning of Distal Radius Fractures

Distal radius fractures are among the most common upper extremity injuries. They account for one sixth of all fractures treated in the emergency department1 and this incidence is expected to increase as the population ages. Thompson and colleagues report that the incidence of distal radius fractures continues to rise with age in women older than 50 and in men older than 65.2

Many different treatment methods have been advocated depending on the fracture type and stability. Various authors have attempted to identify factors that predict instability in distal radius fractures. Mackenney and coworkers found that the most consistent predictors of instability were patient age, metaphyseal comminution, and ulnar variance.3

Many methods of percutaneous pinning have been described in the literature, including trans-styloid pinning, intrafocal pinning, and pinning into the distal fragments.4–10

This technique was originally described by Kapandji in 1976 as a method of treating unstable extra-articular distal radius fractures.11 His original report described a technique whereby two threaded K-wires were inserted into the fracture site and then used to directly manipulate and lever the distal fracture fragment into the desired position. Once reduction was achieved, the wires were advanced into the proximal fragment; the pins do not fix the distal fragment but rather buttress it in place. In the original description, patients were not immobilized postoperatively. Kapandji originally advocated this technique for younger patients, whose fractures were only minimally comminuted. It was contraindicated in patients with osteoporotic bone or severe comminution and in fractures with intra-articular extension. In the original publication, little information was available regarding the clinical results of this procedure.11

In 1987, Kapandji reported his experience with the original technique and recommended adding a third dorsal ulnar pin.12 He expanded the indications to include fractures with multiple fragments.12 Since then, many authors have described modifications to the original technique,11 and the clinical indications have expanded from those originally described.13–21

Literature Review

There are several published case series reporting a large percentage of overall good to excellent results using intrafocal pinning. Epinette and associates reported 83% good and excellent results in 70 cases, including elderly patients and fractures with undisplaced intra-articular extension.13 Docquier and colleagues also reported a high percentage of good and excellent clinical and radiographic results using this technique for articular and extra-articular fractures.14 Peyroux and coworkers reported the outcome of 159 cases (81% extra-articular) with 93% good and excellent clinical results.15

Dowdy and associates retrospectively reviewed the results of 17 patients treated with intrafocal pinning.16 All K-wires were cut below the skin, and the injured area was immobilized for 6 weeks. Sixteen of 17 patients were pleased with their outcomes. The average visual analog score on the pain scale was 0.44/10, and function was 8.6/10. There was a trend for older osteopenic patients to lose their postoperative reduction, but this was not statistically significant.16 Patients aged 65 and older also had significantly less restoration of volar tilt than those younger than 65 years of age (P = .04). Dowdy recommended that Kapandji pinning alone should be avoided in patients with severe osteopenia.

In the largest series published to date, Nonnenmacher and coworkers reported the results of 350 intra-articular and extra-articular distal radius fractures in patients aged 12 to 89 treated with this technique.17 They used three intrafocal pins, which were buried below the skin and removed at 6 weeks. Plaster immobilization was not used, and patients were allowed to begin range of motion postoperatively. The subjective results were good and excellent in 90% of patients, and functional outcomes were reported as good and excellent in 99%. No patients reported poor subjective or functional outcomes. The radiologic results were also evaluated as 93% good to very good, 6% average, and 1% poor.17

The experience with intrafocal pinning in older patients has grown in recent years. Greating and coworkers reported on the results of 24 fractures with minimal intra-articular involvement in patients aged 16 to 94.18 They utilized immobilization in patients for 6 weeks after the surgery. In 13 fractures, the clinical outcomes were excellent in 7, good in 4, and fair in 2 based on the Mayo wrist score. The two fair results were in patients younger than age 65. They also report good and excellent radiologic results (using Sarmiento and colleagues’ criteria22) in 79% of patients younger than 65 and in 60% of patients older than 65. They concluded that this technique provides acceptable clinical results in elderly patients despite some loss of reduction after pinning.

Trumble and coworkers published a review of their experience with intrafocal pinning supplemented with external fixation.19 They reviewed 61 patients with either intrafocal pinning alone or in combination with external fixation. They included fractures with undisplaced intra-articular extension and all age groups. There were 96% good to excellent results in young patients (<55 years) with displaced extra-articular distal radius fractures (minimal comminution) treated with intrafocal pin fixation alone. In patients older than 55 years of age, they reported 94% good to excellent results in patients who received supplemental external fixation and they also reported that range of motion, grip strength, and pain relief were significantly better when external fixation was used in this age group, even when only one cortex demonstrated comminution. Their final recommendation was that older patients, or younger patients with involvement of more than two surfaces of the radial metaphysis (or >50% of the metaphyseal diameter), require external fixation in addition to percutaneous pin fixation for optimal results.19

In a retrospective review by Board and associates comparing closed reduction and casting to intrafocal wiring in patients older than 55 years, it was found that functional results were good to excellent in 19 of 23 patients who received intrafocal pinning versus 12 of 23 who received plaster alone, supporting the use of this technique in older patients.20

Hollevoet recently published a study assessing anterior fracture displacement in Colles’ fractures after intrafocal pinning in women older than age 59 years (without supplemental external fixation).21 It was demonstrated that the intrafocal pins were not sufficient to prevent anterior fracture displacement in almost one third of patients. Five weeks after fracture, 36 of 89 (40.4%) patients had more than 20 degrees of palmar shift or tilt or more than 10 degrees of dorsal angulation; 37 patients (41.6%) had more than 2 mm of ulnar-positive variance; and 6 (6.7%) had more than 5 mm of ulnar-positive variance. The clinical implications of this displacement were not discussed. They concluded that intrafocal wiring of Colles’ fractures in elderly, osteoporotic patients may not be sufficient to prevent anterior fracture displacement.21

Indications

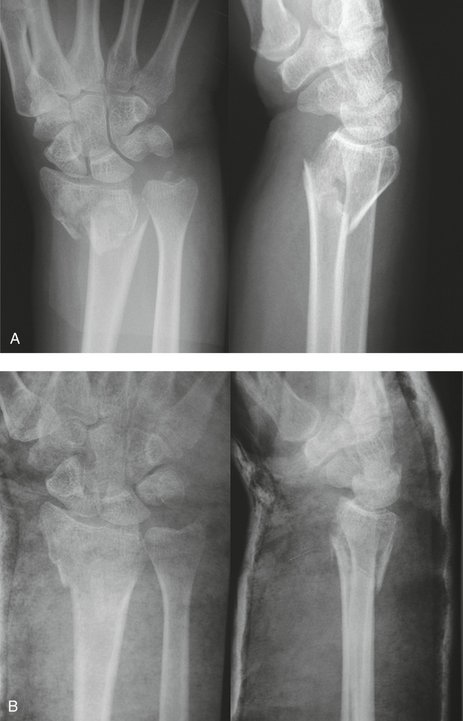

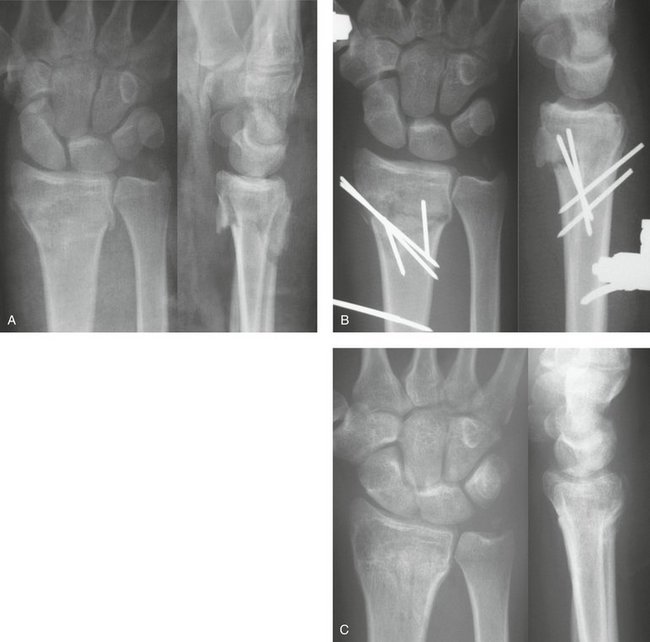

Intrafocal pinning is indicated for unstable displaced distal radius fractures in which it is not possible to obtain or maintain a reduction with cast immobilization (Fig. 17-1). The ideal candidate for Kapandji pinning is a younger patient with good quality bone. Ideally, the fracture should be extra-articular with minimal comminution and easily reducible with closed methods. Since the original description of this technique,11 the indications have expanded to include older patients,13 fractures with undisplaced intra-articular extension,13 and fractures with multiple fragments.12

Contraindications

The intrafocal technique is contraindicated in fractures with significant intra-articular displacement and/or volar cortical comminution.8,18,23 It is also contraindicated if a reduction cannot be achieved by closed means.18,23 Relative contraindications to this technique are poor bone quality and osteoporosis.17 We also avoid intrafocal pinning in patients with severe osteopenia, marked dorsal radial comminution, an associated ipsilateral distal metadiaphyseal ulna fracture, and both volar and dorsal comminution.16 In these circumstances, the Kapandji pins may require supplementation with an external fixator.16,24

Surgical Technique

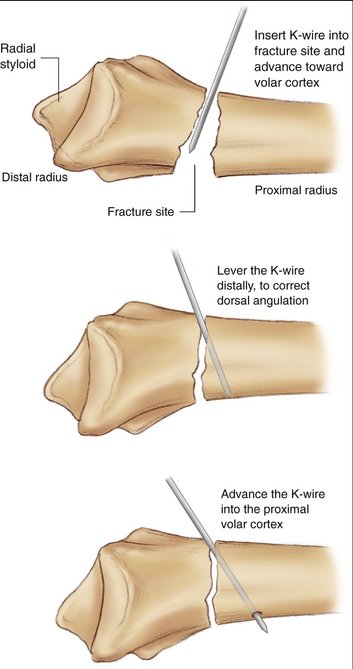

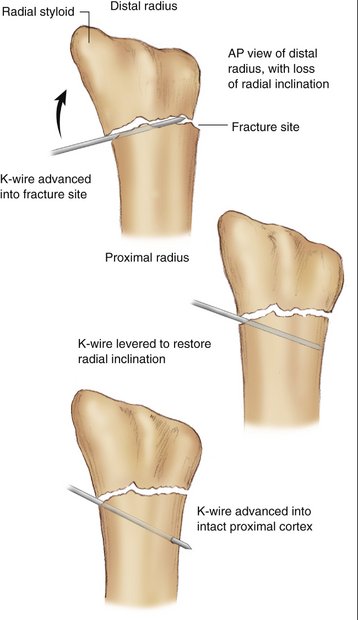

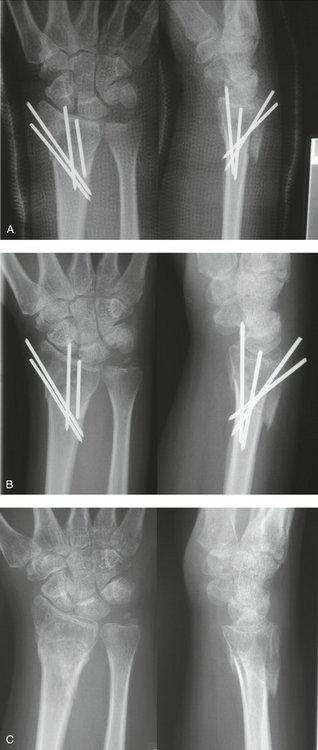

Attention is directed toward first correcting the dorsal tilt. Two 0.062-inch K-wires are percutaneously inserted into the dorsal aspect of the wrist. A dorsal radial pin is inserted between the third and fourth extensor compartments, and a dorsal ulnar pin is inserted between the fourth and fifth extensor compartments. The K-wires are then manually advanced through the dorsal cortex and into the fracture site just short of the volar cortex. The image intensifier facilitates locating the fracture site. These two wires are then levered distally under image control to correct the dorsal tilt (Fig. 17-2). A 0.062-inch K-wire is then inserted percutaneously on the radial aspect of the wrist, between the first and second dorsal compartments, and manually advanced into the fracture site. The K-wire is then levered distally to restore the radial inclination (Fig. 17-3). When an adequate reduction is achieved fluoroscopically, the wires are then advanced through the intact volar and ulnar cortex using a powered wire driver. The final reduction and pin position should then be confirmed radiographically (Fig. 17-4A). Excessive pin protrusion through intact cortex should be avoided to prevent impingement on adjacent structures. The K-wires can then be cut just below the skin but superficial to the extensor tendons to avoid rupture. Alternatively the K-wires can be bent over and cut above the skin. The arm is immobilized in a short arm cast for 6 weeks (see Fig. 17-4B). Early digital motion and forearm rotation are encouraged. At 6 weeks, the K-wires are removed under local anesthetic in the clinic. Range of motion exercises of the wrist are then initiated and supervised by a hand therapist (see Fig. 17-4C).

Potential Pitfalls

Although the procedure is not technically demanding, there are some potential pitfalls to avoid. When advancing the K-wires into the volar cortex, one must ensure that the K-wire does not enter the volar compartment because this may cause nerve or tendon irritation. It is also possible to over-reduce the fracture, cause volar translation of the fragment, or displace an intra-articular fracture. As mentioned previously, these pitfalls can be avoided by monitoring the reduction process with fluoroscopy. One should also consider supplementing intrafocal pinning with an external fixator if the patient is older than 55 years of age or if there is comminution involving more than two surfaces of the radial metaphysis (or >50% of the metaphyseal diameter)19,24 (Fig. 17-5).

Personal Results

We reviewed the experience with extra-articular distal radius fractures at the Hand and Upper Limb Center in London, Ontario, from June 1997 to June 2004. Twenty-eight patients were treated with the intrafocal pinning technique described by Kapandji and were available for 1-year follow-up. All patients were followed at 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year. At each visit, objective clinical data (range of motion and grip strength), radiographs, Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) scores, Patient-Rated Wrist Evaluation (PRWE) scores, and SF-36 scores were obtained.

Clinical Outcomes

The mean PRWE score25 was 17.5 (score 0 to 100, with 100 worst possible score), and the mean DASH score26 was 16.1 (score 0 to 100, with 100 worst possible score). The SF-3627 physical component summary score was 44.4, and the mental component summary score was 51.1 (U.S. population norm = 50).

Radiographic Outcomes

We also evaluated the quality of the reduction according to guidelines of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand (ASSH).28 They indicate that the alignment of a distal radius fracture is considered unacceptable if the dorsal angulation is more than 10 degrees, if the radial inclination is less than 15 degrees, or if there is more than 2 mm of ulnar-positive variance. According to these criteria, 5 of the 28 patients (17.9%) had “unacceptable reductions.” Four of these patients had unacceptable ulnar variance (3.0, 4.5, 4.8, and 5.0 mm), and 1 had excessive volar angulation (23 degrees). Two of the patients with excessive ulnar variance were older than 55 (despite addition of a supplemental external fixator), and one had an infected nonunion.

Complications

The most common complications reported with Kapandji pinning are loss of fracture reduction, extensor tendon rupture, radial sensory nerve irritation, and reflex sympathetic dystrophy.8 Early pin removal, fracture displacement after pinning, and infection are also described.8 In the largest series on Kapandji pinning,17 complications reported include 1 patient with distal radioulnar joint instability, reflex sympathetic dystrophy (8%), need for early pin removal (7%), radial sensory nerve irritation (6%), ulnar neuropathy of the wrist (n = 1), extensor tendinitis (2%), and some displacement of fracture fragments after pinning (14%). It was found that secondary displacement of the fracture did not usually affect the final clinical result.17

In our experience, loss of fracture reduction over time was uncommon, perhaps because all fractures in older patients were supplemented with external fixation. There were four complications in our cohort. There was one patient with reflex sympathetic dystrophy (requiring a stellate ganglion block), one extensor pollicis longus rupture (requiring surgical repair), and one patient requiring early pin removal because of volar migration of the K-wire. In addition, there was one infected nonunion, which occurred despite the wires being buried below the skin.

1. Owen RA, Melton LJ, Johnson KA, et al. Incidence of Colles’ fracture in a North American community. Am J Public Health. 1982;72:605-607.

2. Thompson PW, Taylor J, Dawson A. The annual incidence and seasonal variation of fractures of the distal radius in men and women over 25 years in Dorest, UK. Injury. 2004;35:462-466.

3. Mackenney PJ, McQueen MM, Elton R. Prediction of instability in distal radial fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1944-1951.

4. Duncan S, Weiland AJ. Minimally invasive reduction and osteosynthesis of articular fractures of the distal radius. Injury. 2001;32:14-24.

5. Habernek H, Weinstabl R, Fialka C, Schmid L. Unstable distal radius fractures treated by modified Kirschner wire pinning: anatomic considerations, technique, and results. J Trauma. 1994;36:83-88.

6. Munson GO, Gainor BJ. Percutaneous pinning of distal radius fractures. J Trauma. 1981;21:1032-1035.

7. Naidu SH, Capo JT, Moulton M, et al. Percutaneous pinning of distal radius fractures: a biomechanical study. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1997;22:252-257.

8. Rayhack JM. The history and evolution of percutaneous pinning of displaced distal radius fractures. Orthop Clin North Am. 1993;24:287-300.

9. Ring D, Jupiter JB. Percutaneous and limited open fixation of fractures of the distal radius. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;375:105-115.

10. Rodriguez-Merchan EC. Plaster cast versus percutaneous pin fixation for comminuted fractures of the distal radius in patients between 46 and 65 years of age. J Orthop Trauma. 1997;11:212-217.

11. Kapandji A. L’osteosynthese par double enbrochage intra-focal: traitement fonctionnel des fractures nonarticulaires de l’extrémité inferieure du radius. Ann Chir Main. 1976;30:903-908.

12. Kapandji A. Intra-focal pinning of fractures of the distal end of the radius 10 years later. Ann Chir Main. 1987;6:57-63.

13. Epinette JA, Lehut JM, Cavenaile M, et al. Pouteau-Colles fracture: double-closed ‘basket-like’ pinning according to Kapandji: apropos of a homogeneous series of 70 cases. Ann Chir Main. 1982;1:71-83.

14. Docquier J, Soete P, Twahirwa J, Flament A. Kapandji’s method of intrafocal nailing in Pouteau-Colles fractures. Acta Orthop Belg. 1982;48:794-810.

15. Peyroux LM, Dunaud JL, Caron M, et al. The Kapandji technique and its evolution in the treatment of fractures of the distal end of the radius: report on a series of 159 cases. Ann Chir Main. 1987;6:109-122.

16. Dowdy PA, Patterson SD, King GJ, et al. Intrafocal (Kapandji) pinning of unstable distal radius fractures: a preliminary report. J Trauma. 1996;40:194-198.

17. Nonnenmacher J, Kempf I. Role of intrafocal pinning in the treatment of wrist fractures. Int Orthop. 1988;12:155-162.

18. Greating MD, Bishop AT. Intrafocal (Kapandji) pinning of unstable fractures of the distal radius. Orthop Clin North Am.. 1993;24:301-307.

19. Trumble TE, Wagner W, Hanel DP, et al. Intrafocal (Kapandji) pinning of distal radius fractures with and without external fixation. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1998;23:381-394.

20. Board T, Kocialkowski A, Andrew G. Does Kapandji wiring help in older patients? A retrospective comparative review of displaced intra-articular distal radius fractures in patients over 55 years. Injury. 1999;30:663-669.

21. Hollevoet N, Verdonk R: Anterior fracture displacement in Colles’ fractures after Kapandji wiring in women over 59 years. Int Orthop. 2006; Jul 25 [Epub ahead of print].

22. Sarmiento A, Zagorski JB, Sinclair WF. Functional bracing of Colles’ fractures: a prospective study of immobilization in supination and pronation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980;146:175-183.

23. Stoffelen DV, Broos PL. Closed reduction versus Kapandji pinning for extra-articular distal radial fractures. J Hand Surg [Br]. 1999;24:89-91.

24. Weil WM, Trumble TE. Treatment of distal radius fractures with intrafocal (Kapandji) pinning and supplemental skeletal stabilization. Hand Clin. 2005;21:317-328.

25. MacDermid JC, Turgeon T, Richards RS, et al. Patient rating of wrist pain and disability: a reliable and valid measurement tool. J Orthop Trauma. 1998;12:577-586.

26. Beaton DE, Katz JN, Fossel AG, et al. Measuring the whole or the parts? Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand outcome measure in different regions of the upper extremity. J Hand Ther. 2001;14:128-146.

27. McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31:247-263.

28. eRADIUS International Distal Radius Fracture Study Group. Basic knowledge (Indications for reduction in distal radius fractures). http://www.eradius.com.