Chapter 149 Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

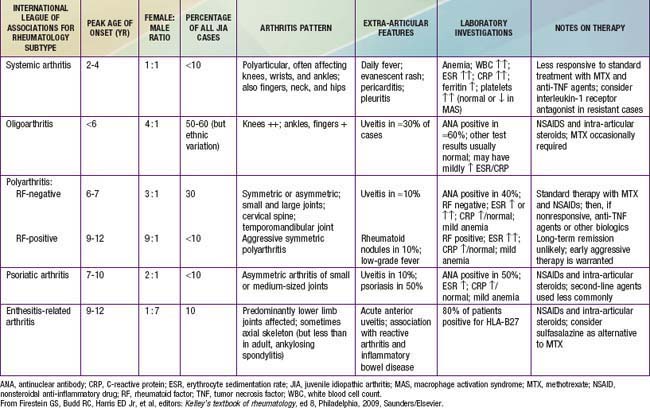

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) (formerly juvenile rheumatoid arthritis) is the most common rheumatic disease in children and one of the more common chronic illnesses of childhood. JIA represents a heterogeneous group of disorders all sharing the clinical manifestation of arthritis. The etiology and pathogenesis of JIA are largely unknown, and the genetic component is complex, making clear distinction among various subtypes difficult. As a result, several classification schemas exist, each with its own limitations. In the Classification Criteria of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), the term juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) is utilized and categorizes disease into 3 onset types (Table 149-1). Attempting to standardize nomenclature, The International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR) proposed use of a different classification using the term juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) (Table 149-2), which is inclusive of all subtypes of chronic juvenile arthritis. We refer to the ILAR classification criteria; enthesitis-related arthritis and psoriatic JIA are covered in Chapter 150 (Tables 149-3 and 149-4).

Table 149-1 CRITERIA FOR THE CLASSIFICATION OF JUVENILE RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

Modified from Cassidy JT, Levison JE, Bass JC, et al: A study of classification criteria for a diagnosis of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, Arthritis Rheum 29;174–181, 1986.

Table 149-2 CHARACTERISTICS OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF RHEUMATOLOGY (ACR) AND INTERNATIONAL LEAGUE OF ASSOCIATIONS FOR RHEUMATOLOGY (ILAR) CLASSIFICATIONS OF CHILDHOOD CHRONIC ARTHRITIS

| PARAMETER | ACR (1977) | ILAR (1997) |

|---|---|---|

| Term | Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) | Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) |

| Minimum duration | ≥6 wk | ≥6 wk |

| Age at onset | <16 yr | <16 yr |

| ≤4 joints in 1st 6 mo after presentation | • Pauciarticular | |

| >4 joints in 1st 6 mo after presentation | • Polyarticular | |

| Fever, rash, arthritis | • Systemic | • Systemic |

| Other categories included | Exclusion of other forms | |

| Inclusion of psoriatic arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, ankylosing spondylitis | No (Chapter 150) | Yes |

Table 149-3 INTERNATIONAL LEAGUE OF ASSOCIATIONS FOR RHEUMATOLOGY CLASSIFICATION OF JUVENILE IDIOPATHIC ARTHRITIS (JIA)

| CATEGORY | DEFINITION | EXCLUSIONS |

|---|---|---|

| Systemic-onset JIA |

Arthritis in ≥1 joints with, or preceded by, fever of at least 2 wk in duration that is documented to be daily (“quotidian”*) for at least 3 days and accompanied by ≥1 of the following:

|

|

| Oligoarticular JIA | ||

| Polyarthritis (RF-negative) | Arthritis affecting ≥5 joints during the 1st 6 mo of disease; a test for RF is negative. | a, b, c, d, e |

| Polyarthritis (RF-positive) | Arthritis affecting ≥5 joints during the 1st 6 mo of disease; ≥2 tests for RF at least 3 mo apart during the 1st 6 mo of disease are positive. | a, b, c ,e |

| Psoriatic arthritis | Arthritis and psoriasis, or arthritis and at least 2 of the following: | b, c, d, e |

| 1. Dactylitis.‡ | ||

| 2. Nail pitting§ and onycholysis. | ||

| 3. Psoriasis in a 1st-degree relative. | ||

| Enthesitis-related arthritis | Arthritis and enthesitis,| or arthritis or enthesitis with at least 2 of the following: | a, d, e |

| Undifferentiated arthritis | Arthritis that fulfills criteria in no category or in ≥2 of the above categories. |

RF, rheumatoid factor.

* Quotidian fever is defined as a fever that rises to 39°C once a day and returns to 37°C between fever peaks.

† Serositis refers to pericarditis, pleuritis, or peritonitis, or some combination of the three.

‡ Dactylitis is swelling of ≥1 digits, usually in an asymmetric distribution, that extends beyond the joint margin.

§ A minimum of 2 pits on any one or more nails at any time.

| Enthesitis is defined as tenderness at the insertion of a tendon, ligament, joint capsule, or fascia to bone.

¶ Inflammatory lumbosacral pain refers to lumbosacral pain at rest with morning stiffness that improves on movement.

From Firestein GS, Budd RC, Harris ED Jr, et al, editors: Kelley’s textbook of rheumatology, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2009, Saunders/Elsevier.

Pathogenesis

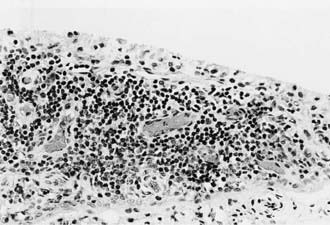

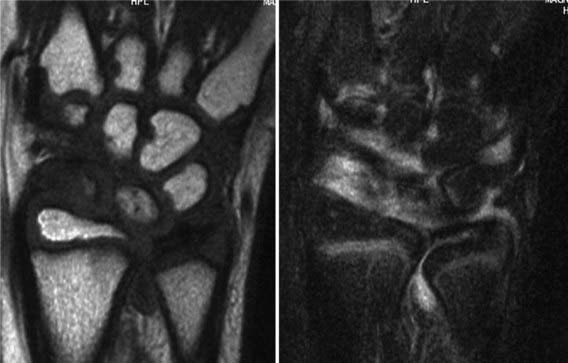

All these immunologic abnormalities cause inflammatory synovitis, characterized pathologically by villous hypertrophy and hyperplasia with hyperemia and edema of the synovial tissue. Vascular endothelial hyperplasia is prominent and is characterized by infiltration of mononuclear and plasma cells with a predominance of T lymphocytes (Fig. 149-1). Advanced and uncontrolled disease leads to pannus formation and progressive erosion of articular cartilage and contiguous bone (Figs. 149-2 and 149-3).

Figure 149-3 MRI with gadolinium of a 10 yr old child with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (same patient as in Fig. 149-1). The dense white signal in the synovium near the distal femur, proximal tibia, and patella reflects inflammation. MRI of the knee is useful to exclude ligamentous injury, chondromalacia of the patella, and tumor.

Clinical Manifestations

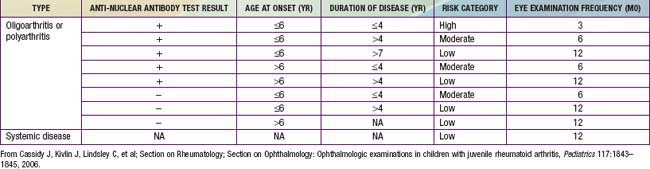

Oligoarthritis is defined as involving ≤4 joints within the first 6 mo of disease onset, predominantly affecting the large joints of the lower extremities, such as the knees and ankles (Fig. 149-4). Often only a single joint is involved. Isolated involvement of upper extremity large joints is less common. Those in whom disease never develops in more than 4 joints are regarded as having persistent oligoarticular JIA, whereas evolution of disease in more than 4 joints over time changes the classification to extended oligoarticular JIA. The latter often portends a worse prognosis. Involvement of the hip is almost never a presenting sign and suggests a spondyloarthropathy (Chapter 150) or nonrheumatologic cause. The presence of a positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) test result confers increased risk for asymptomatic anterior uveitis, requiring periodic slit-lamp examination (Table 149-5).

Figure 149-4 Oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis with swelling and flexion contracture of the right knee.

Polyarthritis (polyarticular disease) is characterized by inflammation of ≥5 joints in both upper and lower extremities (Figs. 149-5 and 149-6). When rheumatoid factor (RF) is present, polyarticular disease resembles the characteristic symmetric presentation of adult rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatoid nodules on the extensor surfaces of the elbows and over the Achilles tendons, although unusual, are associated with a more severe course and almost exclusively occur in RF-positive individuals. Micrognathia reflects chronic temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disease (Fig. 149-7). Cervical spine involvement (Fig. 149-8), manifesting as decreased neck extension, occurs with a risk of atlantoaxial subluxation and neurologic sequelae. Hip disease may be subtle, with findings of decreased or painful range of motion on exam (Fig. 149-9).

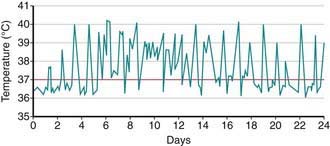

Systemic-onset disease (SoJIA) is characterized by arthritis, fever, and prominent visceral involvement, including hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and serositis (pericarditis). The characteristic fever, defined as spiking temperatures to ≥39°C, occurs on a daily or twice-daily basis for at least 2 wk, with a rapid return to normal or subnormal temperatures (Fig. 149-10). The fever is often present in the evening and is frequently accompanied by a characteristic faint, erythematous, macular rash. The evanescent salmon-colored lesions classic for systemic-onset disease are linear or circular and are most commonly distributed over the trunk and proximal extremities (Fig. 149-11). The classic rash is nonpruritic and migratory with lesions lasting <1 hr. Fever, rash, hepatosplenomegaly, and lymphadenopathy are present in >70% of affected children. Koebner phenomenon, a cutaneous hypersensitivity to superficial trauma, is often present. Heat, such as from a warm bath, also evokes rash. Without arthritis, the differential diagnosis includes the episodic fever syndromes and a fever of unknown origin. Some children initially present with only systemic features, but definitive diagnosis requires presence of arthritis. Arthritis may affect any number of joints, but the course is classically polyarticular, may be very destructive, and includes hip, cervical spine, and TMJ involvement.

Figure 149-10 High-spiking intermittent fever in a 3 yr old patient with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

(From Ravelli A, Martini A: Juvenile idiopathic arthritis, Lancet 369:767–778, 2007.)

Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) is a rare but potentially fatal complication of SoJIA that can occur at anytime during the disease course. It is also referred to as secondary hemophagocytic syndrome or hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) (Chapter 501). MAS classically manifests as acute onset of profound anemia associated with thrombocytopenia or leukopenia with high, spiking fevers, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly. Patients may have purpura and mucosal bleeding, as well as elevated fibrin split product values and prolonged prothrombin and partial prothromboplastin times. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) falls because of hypofibrinogenemia and hepatic dysfunction, a feature useful in distinguishing MAS from a flare of systemic disease. The diagnosis is suggested by clinical criteria and is confirmed by bone marrow biopsy demonstrating hemophagocytosis (Table 149-6). Emergency treatment with high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone, cyclosporine, or anakinra may be effective. Severe cases may require therapy similar to that for primary HLH (Chapter 501).

Table 149-6 PRELIMINARY DIAGNOSTIC GUIDELINES FOR MACROPHAGE ACTIVATION SYSTEM (MAS) COMPLICATING SYSTEMIC JUVENILE IDIOPATHIC ARTHRITIS (JIA)

LABORATORY CRITERIA

CLINICAL CRITERIA

HISTOPATHOLOGIC CRITERION

• Evidence of macrophage hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow aspirate

DIAGNOSTIC RULE

• The diagnosis of MAS requires the presence of any 2 or more laboratory criteria or of any 2 or 3 or more clinical and/or laboratory criteria. A bone marrow aspirate for the demonstration of hemophagocytosis may be required only in doubtful cases.

RECOMMENDATIONS

• The aforementioned criteria are of value only in patients with active systemic JIA. The thresholds of laboratory criteria are provided by way of example only.

COMMENTS

From Ravelli A, Magni-Manzoni S, Pistorio A, et al: Preliminary diagnostic guidelines for macrophage activation syndrome complicating systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, J Pediatr 146:598–604, 2005.

Diagnosis

JIA is a clinical diagnosis of exclusion with many mimics and without diagnostic laboratory tests. The meticulous clinical exclusion of other diseases is therefore essential. See Tables 149-1 to 149-4 for classification criteria. Laboratory studies, including tests for ANA and RF, are only supportive and their results may be normal in patients with JIA.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for arthritis is broad and a careful, thorough investigation for other underlying etiology is imperative. Findings of the history, physical exam, laboratory tests, and radiography help exclude other possible causes. Arthritis can be a presenting manifestation for any of the multisystem rheumatic diseases of childhood, including systemic lupus erythematosus (Chapter 152), juvenile dermatomyositis (Chapter 153), sarcoidosis (Chapter 159), and the vasculitic syndromes (Chapter 161) (Table 149-7). In scleroderma (Chapter 154), limited range of motion due to sclerotic skin overlying a joint may be confused with sequelae from chronic inflammatory arthritis. Acute rheumatic fever is characterized by exquisite joint pain and tenderness, a remittent fever, and a migratory polyarthritis. Autoimmune hepatitis can also be associated with an acute arthritis.

Table 149-7 CONDITIONS CAUSING ARTHRITIS OR EXTREMITY PAIN

RHEUMATIC AND INFLAMMATORY DISEASES

SERONEGATIVE SPONDYLOARTHROPATHIES

INFECTIOUS ILLNESSES

REACTIVE ARTHRITIS

IMMUNODEFICIENCIES

CONGENITAL AND METABOLIC DISORDERS

BONE AND CARTILAGE DISORDERS

NEUROPATHIC DISORDERS

NEOPLASTIC DISORDERS

HEMATOLOGIC DISORDERS

MISCELLANEOUS DISORDERS

PAIN SYNDROMES

Many infections are associated with arthritis, and a recent history of infectious symptoms may help make a distinction. Viruses, including parvovirus B19, rubella, Epstein-Barr virus, hepatitis B virus, and HIV, can induce a transient arthritis. Arthritis may follow enteric infections (Chapter 151). Lyme disease (Chapter 214) should be considered in children with oligoarthritis living in or visiting endemic areas. Although a history of tick exposure, preceding flu-like illness, and subsequent rash should be sought, they are not always present. Monoarticular arthritis unresponsive to anti-inflammatory treatment may be the result of chronic mycobacterial or other infection such as Kingella kingae, and the diagnosis is established by synovial fluid analysis or biopsy. Acute onset of fever and a painful, erythematous, hot joint suggests septic arthritis. Isolated hip pain with limited motion raises the possibility of suppurative arthritis (Chapter 677), osteomyelitis, toxic synovitis, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, slipped capital femoral epiphysis, and chondrolysis of the hip (Chapter 670).

Tenderness over insertion of ligaments and tendons and lower extremity arthritis, especially in a boy, raises the possibility of a spondyloarthropathy (Chapter 150). Psoriatic arthritis can manifest as limited joint involvement in an unusual distribution (e.g., small joints of the hand and ankle) years prior to onset of cutaneous disease. Inflammatory bowel disease may manifest as oligoarthritis, usually affecting joints in the lower extremities, as well as gastrointestinal symptoms, elevations in ESR, and microcytic anemia.

Many conditions present solely with arthralgias (i.e., joint pain). Hypermobility may cause joint pain, especially in the lower extremities. Growing pains should be suspected in a child between the ages of 4 to 12 yr complaining of leg pain in the evenings with normal investigative studies and no morning symptoms. Nocturnal pain also alerts to the possibility of a malignancy. An adolescent with missed school days may suggest a diagnosis of fibromyalgia (Chapter 162).

Children with leukemia or neuroblastoma may have joint or bone pain resulting from malignant infiltration of the bone, synovium, or, more often, the bone marrow, sometimes months before demonstrating lymphoblasts on peripheral blood smear. Physical examination may reveal no tenderness or a deeper pain to palpation of the bone or pain out of proportion to exam findings. Malignant pain often awakens the child from sleep and may cause cytopenias. Because platelets are an acute-phase reactant, a high ESR with leukopenia and a low normal platelet count may also be a clue to underlying leukemia. In addition, the characteristic quotidian fever of JIA is absent in malignancy. Bone marrow examination is necessary for diagnosis. Some diseases, such as cystic fibrosis, diabetes mellitus, and the glycogen storage diseases, have associated arthropathies (Chapter 163). Swelling that extends beyond the joint can be a sign of lymphedema or Henoch-Schönlein purpura. A peripheral arthritis indistinguishable from JIA occurs in the humoral immunodeficiencies, such as common variable immunodeficiency and X-linked agammaglobulinemia. Skeletal dysplasias associated with a degenerative arthropathy are diagnosed from their characteristic radiologic abnormalities.

Laboratory Findings

Early radiographic changes of arthritis include soft tissue swelling, periarticular osteoporosis, and periosteal new-bone apposition around affected joints (Fig. 149-12). Continued active disease may lead to subchondral erosions and loss of cartilage, with varying degrees of bony destruction and, potentially, fusion. Characteristic radiographic changes in cervical spine, most frequently in the neural arch joints at C2-C3 (see Fig. 149-8) may progress to atlantoaxial subluxation. MRI is more sensitive than radiography to early changes (Fig. 149-13).

Treatment

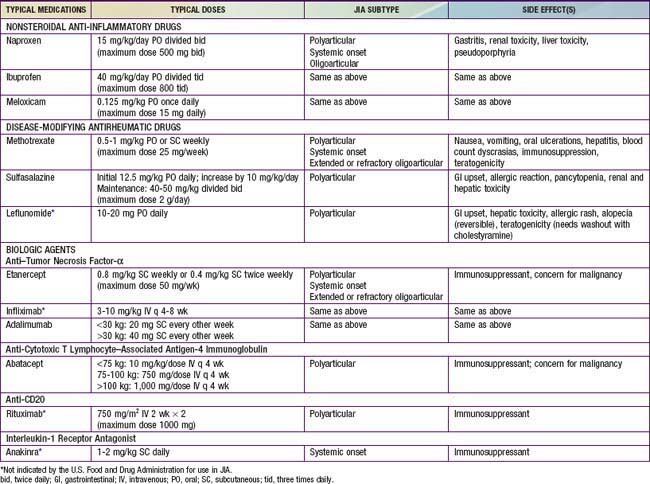

The goals of treatment are to achieve disease remission, prevent or halt joint damage, and foster normal growth and development. All children with JIA need individualized treatment plans, and management is tailored according to disease subtype and severity, presence of poor prognostic indicators, and response to medications. Disease management also requires monitoring for potential medication toxicities. Please see Chapter 148 for a detailed discussion of the medications used in the treatment of rheumatic diseases.

Children with oligoarthritis often show at least partial response to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), with improvement in inflammation and pain (Table 149-8). Those who have no response after 4-6 wk of treatment with NSAIDS or who have functional limitations, such as joint contracture or leg length discrepancy, benefit from injection of intra-articular corticosteroids. Triamcinolone hexacetonide is a long-lasting preparation that provides a prolonged response. A minority of patients with oligoarthritis show no response to NSAIDs and injections, so require treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), like patients with polyarticular disease.

Management of JIA must include periodic slit-lamp ophthalmologic examinations to monitor for asymptomatic uveitis (see Table 149-5). Optimal treatment of uveitis requires collaboration between the ophthalmologist and rheumatologist. Initial management of uveitis may include mydriatics and corticosteroids used topically, systemically, or through periocular injection. DMARDs allow for a decrease in exposure to steroids, and methotrexate and monoclonal antibodies to TNF-α (adalimumab and infliximab) are effective in treating severe uveitis.

Prognosis

Children with persistent oligoarticular disease fare well, with a majority achieving disease remission. Those in whom more extensive disease develops have a poorer prognosis. Children with oligoarthritis, particularly girls who are ANA positive and with onset of arthritis earlier than 6 yr of age are at risk for development of chronic uveitis. There is no association between the activity or severity of the arthritis and the chronic uveitis. Persistent, uncontrolled anterior uveitis (Fig. 149-14) can cause posterior synechiae, cataracts, and band keratopathy, and can result in blindness. Many of these children do well with early diagnosis and implementation of therapy.

Behrens EM, Beukelman T, Gallo L, et al. Evaluation of the presentation of systemic onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: Data from the Pennsylvania Systemic Onset Juvenile Arthritis Registry (PASOJAR). J Rheumatol. 2008;35:343-348.

Beresford MW, Baildam EM. New advances in the management of juvenile idiopathic arthritis—1: non-biological therapy. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2009;94:144-150.

Bongartz T. Tocilizumab for rheumatoid and juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet. 2008;371:961-964.

Cassidy J, Kivlin J, Lindsley C, et al. Ophthalmologic examinations in children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1843-1845.

Cohen SB, Emery P, Greenwald MW, et al. Rituximab for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial evaluating primary efficacy and safety at twenty-four weeks. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2793-2806.

Flatø B, Lien G, Smerdel A, et al. Prognostic factors in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: a case control study revealing early predictors and outcome after 14.9 years. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:386-393.

Foell D, Wulffraat N, Wedderburn LR, et al. Methotrexate withdrawal at 6 vs 12 months in juvenile idiopathic arthritis in remission. JAMA. 2010;303:1266-1273.

Furst DE, Breedveld FC, Kalden JR, et al. Updated consensus statement on biological agents for the treatment of rheumatic diseases, 2007. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(Suppl III):iii2-iii22.

Gattorno M, Piccini A, Lasiglie D, et al. The pattern of response to anti-interleukin-1 treatment distinguishes two subsets of patients with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1505-1515.

Hashkes PJ, Laxer RM. Medical treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. JAMA. 2005;294:1671-1684.

Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States: part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:15-25.

Hot A, Toh ML, Coppere B, et al. Reactive hemophagocytic syndrome in adult-onset still disease. Medicine. 2010;89:37-46.

LeBovidge JS, Lavigne JV, Donenberg GR, et al. Psychological adjustment of children and adolescents with chronic arthritis: a meta-analytic review. J Pediatric Psychol. 2003;28:29-39.

Lovell DJ, Reiff A, Jones OY, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of etanercept in children with polyarticular-course juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1987-1994.

Lovell DJ, Ruperto N, Goodman S, et al. Adalimumab with or without methotrexate in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. New Engl J Med. 2008;359:810-820.

Packham JC, Hall MA. Long-term follow-up of 246 adults with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: functional outcome. Rheumatology. 2002;41:1428-1435.

Petty RE, Southwood TR, Manners P, et al. International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR) classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:390-392.

Prince FHM, Otten MH, van Suijlekom-Smit WA. Diagnosis and management of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. BMJ. 2011;342:95-102.

Ramanan AV, Grom AA. Does systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis belong under juvenile idiopathic arthritis? Rheumatology. 2005;44:1350-1353.

Ranganathan P, Culverhouse R, Marsh S, et al. Methotrexate (MTX) pathway gene polymorphisms and their effects on MTX toxicity in Caucasian and African American patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:572-579.

Ravelli A, Magni-Manizoni S, Pistorio A, et al. Preliminary diagnostic guidelines for macrophage activation syndrome complicating systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Pediatr. 2005;146:598-604.

Ravelli A, Martini A. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet. 2007;369:767-778.

Reiff A. The use of anakinra in juvenile arthritis. Curr Rheum Reports. 2005:434-440.

Ruperto N, Lovell DJ, Cuttica R, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of infliximab plus methotrexate for the treatment of polyarticular-course juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3096-3106.

Ruperto N, Lovell DJ, Quartier P, et al. Abatacept in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled withdrawal trial. Lancet. 2008;372:383-391.

Scott DL, Wolfe F, Huizinga TWJ. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2010;376:1094-1106.

Silverman E, Mouy R, Spiegel L, et al. Leflunomide or methotrexate for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1655-1666.

Wittkowski H, Frosch M, Wulffraat N, et al. S100A12 is a novel molecular marker differentiating systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis from other causes of fever of unknown origin. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3924-3931.

Yokota S, Imagawa T, Mori M, et al. Efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in patients with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, withdrawal phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;371:998-1006.