107 Joint Disorders

• A white blood cell count higher than 50,000/mm3 is suggestive of a septic joint; however, lower counts do not rule out this diagnosis. If the index of clinical suspicion for a septic joint is high but the test results are nondiagnostic, the disorder should be treated as an infection.

• Severely painful acute monarticular arthritis, with or without fever, is highly likely to be a septic joint; it is an emergency requiring parenteral antibiotics and possible surgical intervention.

• Joint prostheses, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, concurrent infection, and age older than 80 years are significant risk factors for bacterial joint infections. Acute problems in a prosthetic joint merit immediate discussion with an orthopedic surgeon.

• A sexually active young adult with an inflamed, painful joint is considered to have gonococcal arthritis until proved otherwise and should be treated accordingly.

• Gout and pseudogout are crystal-induced arthritides that although benign, may cause significant pain and morbidity. The patient’s pain can be significantly improved by anesthetic and steroid injection after arthrocentesis.

• Overlying soft tissue infection may preclude arthrocentesis or warrant a different approach.

• Syncope may be a warning of high risk for sudden cardiac death in patients with systemic inflammatory arthritides.

• Cervical spine disease is common with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis and must be considered before any attempt at endotracheal intubation that involves forced flexion.

• Serious complications of arthritides are rare but may be life- or limb-threatening.

Arthritis

Epidemiology

An estimated 20 million people in the United States have osteoarthritis (OA), and 2 to 3 million have rheumatoid arthritis (RA). The total cost of medical care, lost work time, and disability for OA alone is estimated to run 2% of the gross national product. The most common cause of joint pain is OA, but the most crucial challenge is identification of a septic joint. Septic arthritis occurs in all age groups but is more common in children than in adults, and about 10% of patients with an acutely painful joint will be found to have infection.1

Pathophysiology

The structure of diarthrodial joints (the most common type) includes the synovium, synovial fluid, articular cartilage, intraarticular ligaments, joint capsule, and juxtaarticular subchondral bone. The delicate synovium provides oxygen and nutrients to cartilage and produces lubricants. Articular cartilage deforms under mechanical load to minimize stress and provides a smooth surface for joint motion with minimal friction. Causes of joint disorders (Box 107.1) often overlap. Cumulative microdamage and remodeling occur with use and aging. Mechanical or metabolic disturbances may lead to a secondary inflammatory response, or an inflamed structure (e.g., a tendon) may rupture. Arthrosis is due to a mechanical insult, whereas arthritis is due to inflammation of the synovium. With inflammation comes white blood cell (WBC) infiltration, release of cytokines (e.g., tumor necrosis factor-α [TNF-α], interleukins) and other inflammatory mediators, and proliferation of cells or tissue. Edema collects around the joint, which causes stiffness. With prolonged inflammation, erosion of bone and destruction of the joint eventually occur and can produce deformity and chronic disability.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

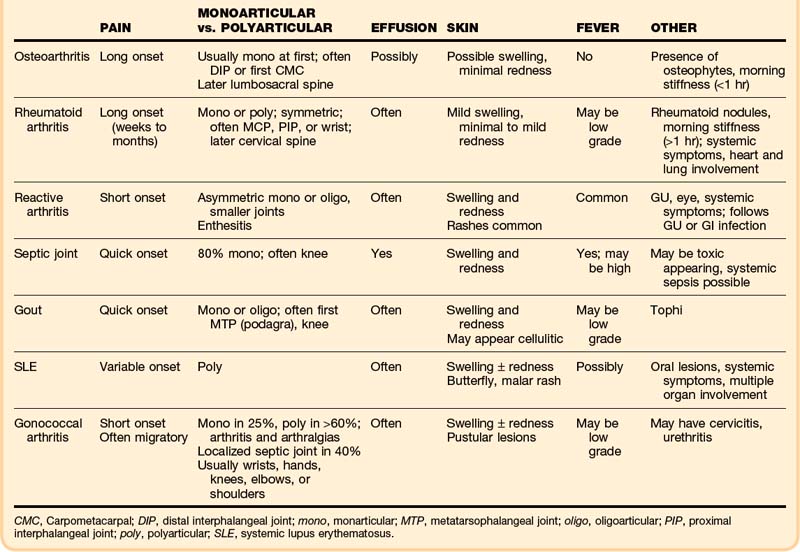

The clinical findings can narrow the potential cause of a patient’s symptoms (Table 107.1). Initial assessment must determine whether the anatomic site of the problem is the joint and then a general category of the disease, either inflammatory (septic versus aseptic) or noninflammatory (mechanical). A red, hot, swollen, painful joint is the classic finding with septic and other inflammatory arthritides. Arthritis patients may also have serious nonarticular complications of their disease or its treatment.

The onset and pattern of pain are important to determine (Box 107.2). Mechanical pain is worse with use, rapidly relieved with rest, and often least in the morning. If present, morning stiffness resolves quickly. Rapid onset over a period of minutes suggests trauma, internal derangement, or a loose fragment in the joint. Inflammatory pain is often worse with use as well, but not so quickly relieved with rest, and is commonly associated with morning stiffness (short duration with OA, prolonged with RA). “Gelling” (stiffness and immobility) after sitting in one position occurs with either type. Widespread pain with stiffness is typically due to inflammatory arthritis or fibromyalgia. Subjective pain without joint findings on examination is termed arthralgia. If the patient has tried medications without relief, the dosage should be determined because inadequate dosing is common.

Box 107.2 Key Historical Points

What is the source and type of pain?

What is the OPQRST (onset, palliation/aggravation, quality, radiation, severity, timing)?

Medications, especially thiazides (can increase serum uric acid), isoniazid, procainamide, and hydralazine (can precipitate lupus)?

Current and previous treatments? Nontraditional remedies? Results?

The musculoskeletal examination attempts to identify the exact site of the problem—joint versus bone, muscle, periarticular, or superficial skin pain. Particular joint involvement may aid in making the diagnosis (Box 107.3). True joint pain is usually diffuse on palpation and increases with active and passive motion. Periarticular inflammation (tendonitis, bursitis, cellulitis) is generally more focal, with pain reproduced only by certain movements—most often resisted active contraction or passive stretching of the involved muscles or tendons and usually only toward one side.

Box 107.3 Articular Diseases Associated with Joint Location

By Specific Joint or Joints

First metatarsophalangeal (MTP): Gout

Knee: Septic arthritis, pseudogout, gout, OA

Metacarpophalangeal, MTP, proximal interphalangeal, tarsometatarsal, and cervical spine: RA

Distal and proximal interphalangeal, first carpometacarpal, knee, hip, cervical and lumbosacral spine: OA

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Mechanical, inflammatory, or metabolic causes of arthritis may be present, and the whole picture must be considered in narrowing the lengthy differential diagnosis (Box 107.4). A new diagnosis of a specific type of inflammatory arthritis may not be possible in one visit, but recognition that the case is inflammatory is important for interim care. The severity of a patient’s discomfort will determine the urgency of analgesia, which may be initiated well before refining the list of possible diagnoses.

Box 107.4 Differential Diagnoses for Acute Arthritis

Noninflammatory Joint Disorder

Avascular necrosis of the hip (including Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease*)

Charcot (neuropathic) arthropathy

Hemarthrosis, hemophilic arthropathy

Hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy

Inherited storage diseases (e.g., Gaucher)

Liquid lipid microsphere disease

Pigmented villonodular synovitis

Inflammatory Joint Disorder

Connective tissue diseases: systemic lupus erythematosus, scleroderma, Sjögren syndrome, mixed connective tissue disease

Crystal deposition: gout, pseudogout

Drug reaction (serum sickness)

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis and subtypes*

Osteoarthritis, degenerative joint disease

Polymyalgia rheumatica with joint involvement

Diagnostic Studies

Blood tests are rarely diagnostic in patients with synovial disorders but may be ordered sparingly to assist in management decisions. A complete blood count (CBC) and basic chemistry profile will identify anemia, an elevated WBC count, and renal dysfunction (which affects selection of medications). The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) are nonspecific but useful markers of inflammation. Coagulation studies are needed only if a patient is taking anticoagulants or a bleeding disorder is suspected. Creatine phosphokinase is helpful if muscle pain or weakness is detected. If clinical assessment raises concern for other autoimmune or systemic diseases, additional screening for multiorgan involvement with urinalysis, liver enzymes, electrocardiogram, and chest films may help. Serologic testing (e.g., rheumatoid factor [RF], antinuclear antibody, and Lyme serology, depending on the clinical impression) is generally done in follow-up settings.2

Plain radiographs are ordered if a fracture, foreign body, septic joint, or tumor is suspected. If the initial films show no fracture but suspicion remains, films repeated in 1 to 2 weeks may show callus formation or abnormal alignment. Radiographic findings may also assist in diagnosing the type of arthritis (Box 107.5),3 although they may remain normal early in the course. The presence of degenerative changes in a painful joint supports the clinical suspicion of OA as the cause, but such changes also become common with age, even in asymptomatic joints; conversely, a normal film does not rule out OA. Similarly, calcified fibrocartilage is often found in patients with calcium pyrophosphate deposition (CPPD) disease but is common in asymptomatic patients as well. Ultrasonography is useful in confirming joint effusion, especially in joints that are difficult to assess, such as the hip. Other modalities are rarely indicated in the emergency department (ED). Although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can distinguish synovitis from effusion and identify rotator cuff tears or be used to evaluate ligament trauma, emergency MRI or computed tomography (CT) is indicated only if a severe joint complication is strongly suspected or if axial skeletal pain merits evaluation for stenosis or metastatic disease.

Box 107.5

“Seconds” Mnemonic for Radiographic Evaluation of Arthritis

Soft tissue swelling—Nonspecific, often seen with acute arthritides such as gout, pseudogout, and septic arthritis, as well as with tuberculous arthritis; also present in trauma

Erosions—May be present in late rheumatoid arthritis as a result of the pannus eroding into articular cartilage and bone

Calcification—In late pseudogout, there may be linear calcification in cartilage

Osteoporosis—Sometimes present in late septic arthritis as a result of joint destruction (about 8 to 10 days of disease before changes are evident on plain films). Osteoporosis or periarticular bone may be seen with late rheumatoid arthritis but not with pseudogout or osteoarthritis

Narrowing of the joint space—Present in late septic arthritis; asymmetric narrowing is consistent with late pseudogout and osteoarthritis; symmetric narrowing is consistent with late rheumatoid arthritis. Joint space is typically preserved with tuberculous arthritis

Deformity—In late septic arthritis, subchondral bone destruction and periosteal new bone may be visualized; in late pseudogout and osteoarthritis, changes may include sclerosis, osteophyte formation, and subchondral cyst formation

Adapted from Beachley MC, Franklin JW, Ostlund W, et al. Radiology of arthritis. Prim Care 1993;20:771-94.

Arthrocentesis with synovial fluid analysis is an important diagnostic and therapeutic procedure for joint disease (see the Tips and Tricks box and Box 107.6). It is the only reliable means to rule out a septic joint, and it is essential in acute monarthritis to look for joint infection, crystals, or hemarthrosis. Possible complications of arthrocentesis include introduction of infection into the joint space, hemarthrosis, and adverse reactions to medications. Arthrocentesis of prosthetic joints is best done with orthopedic consultation.

Box 107.6 Arthrocentesis

Indications

Diagnosis of nontraumatic joint disease by synovial fluid analysis

Diagnosis of ligamentous or bony injury by confirmation of blood in the joint

Establishment of the existence of an intraarticular fracture by the presence of blood with fat globules in the joint

Relief of pain accompanying acute hemarthrosis or a tense effusion

Local instillation of medications

Obtaining fluid for analysis (culture, cell count, crystal studies)

Tips and Tricks

Joint Fluid Collection

Identify and mark landmarks before infiltration with an anesthetic.

Preprocedure use of an ice pack will decrease pain.

Support the joint in a position of comfort during and after the procedure.

Contact the laboratory technicians before collecting the fluid to verify the following:

Use sonographic localization of joint fluid.

Prepare the area thoroughly with the antiseptic of choice. Use sterile gloves and equipment.

Use an 18- to 22-gauge needle depending on the size of the joint; smaller needles may not be sufficient to collect joint fluid.

Attachment of extension tubing between the needle hub and the syringe helps decrease movement of the needle in the joint space and makes changing syringes with large-volume arthrocentesis and injection of medications into the joint space easier. Tubing must be flushed when injecting corticosteroids so that the full dose actually enters the joint space.

Collect enough fluid for appropriate testing (this is not an easily repeated procedure).

Send fluid for a cell count and differential, Gram stain and culture, crystals, glucose, and viscosity.

Seeding the fluid into blood culture flasks immediately after aspiration may increase the yield.

Have the patient rest the joint for 12 to 24 hours after the injection of corticosteroids.

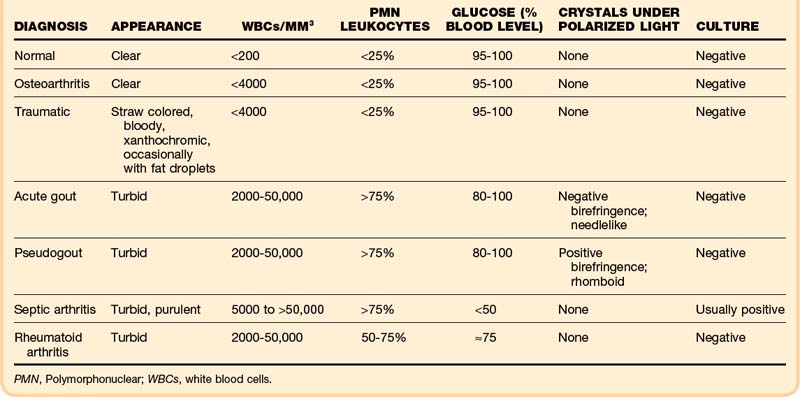

Normal synovial fluid is clear and yellow in appearance. In degenerative joint disease the fluid itself is normal and thus remains clear. Bloody fluid suggests hemarthrosis. Fat droplets may confirm a fracture. Turbid fluid is observed in inflammatory conditions: gout, pseudogout, and septic, rheumatoid and seronegative arthritides (Table 107.2).

Crystal analysis is performed under compensated polarizing microscopy. In patients with acute gout, monosodium urate crystals are present inside neutrophils in fluid from the affected joint. The crystals are typically needle shaped and appear yellow when parallel to the compensator; this is negative birefringence. Sensitivity is at least 85%, and specificity for gout is 100%.4 In pseudogout, the crystals are positively birefringent (blue when parallel to the compensator), usually rhomboid shaped, and also phagocytized by neutrophils. Acute gouty arthritis may occasionally coexist with septic arthritis or pseudogout.

Glucose may be decreased relative to serum glucose in severe inflammatory disorders: down to less than 50% of the serum glucose level in septic arthritis and 50% to 75% in rheumatoid and seronegative arthritides. However, evidence suggests that chemistry studies on joint fluid should be discouraged because their results may be misleading or redundant.5

Although a joint WBC count higher than 50,000/mm3 is generally said to be positive for infection, septic arthritis can occur with lower joint WBC counts, especially early in infection (36% of patients with septic arthritis had joint WBC counts lower than 50,000/mm3).6 In addition, patients with inflammatory arthritides such as RA, gout, and pseudogout may have very high joint WBC counts. Thus fluid must also be sent for Gram stain and culture. The yield is increased by immediate plating in the laboratory and perhaps by inoculating blood culture bottles with joint fluid in the ED. The serum WBC count, ESR, and joint WBC count are extremely variable in adults with septic arthritis.7 In the absence of a positive Gram stain, the ED clinician must consider the whole picture when determining the probability of septic arthritis.

Treatment

Removal of fluid from a joint effusion provides considerable relief. Intraarticular corticosteroids (e.g., triamcinolone hexacetonide, ranging from 5 mg in a finger joint to 40 mg in a large joint, or methylprednisolone, 2 to 5 mg in small joints and 10 to 25 mg in large joints) are recommended for effusions unless infection is suspected. The patient should be informed that the pain relief with corticosteroids typically begins in 1 to 2 days, peaks at about 1 week, and lasts for 1 week to a few months, during which time compliance with adjunctive measures helps prevent recurrence. Although minimal evidence supports the concern, repeated steroid use traditionally raises concern over cartilage damage, so use in the same joint is limited to every 3 to 4 months. Long-acting local anesthetic may be added to the injection for same-day short-term relief.8,9

Follow-up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

Serious situations may warrant admission (Box 107.7). Patients with joint infections require admission and early consultation with an orthopedic surgeon or rheumatologist.

Box 107.7 Emergency Department Disposition Decisions

When to Admit

Inability to control pain without parenteral analgesics

Acute inability to ambulate despite treatment in the emergency department (ED)

Inability to care for self at home (physical and occupational therapy; social, placement issues)

Need for urgent operative intervention

Need for parenteral medications

Possible infection in a prosthetic joint

High-risk complications (e.g., acute renal failure, systemic vasculitis, cardiac involvement, hypoxic lung disease)

Indications for Rheumatology or Orthopedic Outpatient Follow-up

Time Line for Follow-up

In 2 to 3 days: Significant inflammation, serious risk if diagnostic delay, culture results to be checked (if timely outpatient visit not possible, schedule return to the ED)

Within 1 week: Lupus flare (no central nervous system or renal involvement; laboratory results not seriously altered); consultation with a rheumatologist for a possible increase in steroids

In 1 to 2 weeks: Patient with rheumatologic disease sick enough to merit an ED visit but not severely ill; intraarticular corticosteroids administered in the ED; most inflammatory arthritides (not septic)

In 2 to 4 weeks: Chronic, mild, or noninflammatory complaints

Topical analgesics may help, especially if only a single joint is problematic. Topical NSAIDs (diclofenac or ketoprofen, but not salicylates) and capsaicin (thin film of 0.025% cream applied four times per day) have been shown in trials to be beneficial, but maximal relief may take 3 to 4 weeks. Topical NSAIDs avoid the GI and renal complications of oral agents.10,11 Lidocaine patches are another option, although unstudied.

Appropriate lifestyle recommendations for patients with chronic arthritis are to stay as active as possible with daily activities and reasonable exercise programs. Physical and occupational therapy12 may contribute greatly to improved quality of life and ability to maintain independence in self-care but are usually arranged by the continuity physician. Initial range-of-motion (ROM) and later strengthening and aerobic exercise regimens are recommended; swimming pool exercise programs are quite helpful. Obese patients with lower extremity arthritis should be educated about the importance of weight reduction.

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

At Discharge

Instruct patients to return to the emergency department (ED) for temperatures higher than 101° F or if the redness or swelling spreads; also state specific problems to watch out for—for example, patients given nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs should “stop the medicine and come to the ED if you have black or bloody stools.”

Educate patients about their specific condition. Examples of teaching points include the following:

Understanding plus compliance with the recommended medication dose and directions is important for a good outcome. Patients with inflammatory arthritis may benefit from continuing the antiinflammatory medications even after the pain improves.

Follow-up visits are important for a good outcome:

Preprinted discharge instructions and disease education pamphlets are helpful, especially if notes are added to adapt them to the specific needs of individual patients. Additional information is available at sites such as www.arthritisfoundation.org.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Epidemiology

RA is the most common inflammatory arthritis, with about 0.8% of the world’s population afflicted, and it has a 3 : 1 female preponderance. It begins most commonly in the 40s. Overall, life expectancy is only modestly reduced, but quality of life may be significantly impaired. The majority of patients experience chronic remitting but overall progressive disease, including about 10% with an aggressive, severely destructive pattern and 15% to 30% with intermittent remissions lasting up to 1 year; about 15% experience a long-lasting remission with excellent function.13

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

RA is characterized by symmetric polyarthritis persisting for more than 6 weeks, prolonged morning stiffness (>30 minutes), and systemic symptoms of fatigue, malaise, and weight loss. Diagnostic criteria are listed in Table 107.3.14 Arthritis typically starts in the small joints (metacarpophalangeal [MCP], metatarsophalangeal [MTP], and proximal interphalangeal [PIP] joints of the hands and feet but not the distal interphalangeal [DIP] joints) and later affects larger extremity joints. Migratory polyarthralgia occurs, and the symptoms may wax and wane. The onset of RA is typically insidious but can be abrupt. Cervical spine involvement is prevalent, although the rest of the spine is usually spared. RA increases the risk for a septic joint or tendon rupture, and temporomandibular joint (TMF) problems are common.

Table 107.3 2010 American College of Rheumatology Revised Criteria for the Classification of Rheumatoid Arthritis*

| FINDING | POINTS |

|---|---|

| A. Joint Involvement | |

| 1 large joint | 0 |

| 2-10 large joints | 1 |

| 1-3 small joints (with or without the involvement of large joints) | 2 |

| 4-10 small joints (with or without the involvement of large joints) | 3 |

| >10 joints (at least 1 small joint) | 5 |

| B. Serology (at Least 1 Test Result Is Needed for Classification) | |

| Negative RF and negative ACPA | 0 |

| Low positive RF or low positive ACPA | 2 |

| High positive RF or high positive ACPA | 3 |

| C. Acute Phase Reactants (at Least 1 Test Result Is Needed for Classification) | |

| Normal CRP and normal ESR | 0 |

| Abnormal CRP or abnormal ESR | 1 |

| D. Duration of Symptoms | |

| <6 wk | 0 |

| ≥6 wk | 1 |

ACPA, Anti–citrullinated protein antibody; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; RF, rheumatoid factor IgM.

* Score-based algorithm: Add the scores of categories A to D; a score of 6 or higher of a total of 10 is needed for to classify a patient as having definite RA.

Adapted from Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, et al. 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1580-1588.

See Table 107.3, 2010 American College of Rheumatology Revised Criteria for the Classification of Rheumatoid Arthritis, online at www.expertconsult.com

Examination in the early stages usually finds tenderness, swelling, and limited ROM in at least three joints, especially in the hands and feet.15 Warmth and erythema are uncommon. Palpation may reveal loss of the normal contour across joints (especially the MCP joints) because of pannus. Rheumatoid nodules are found in 20% of patients and can appear anywhere but especially over bony prominences, pressure points, and tendon sheaths. These nodules may be fixed or mobile with a rubbery or granular texture and are sometimes indistinguishable from gouty tophi. They are not a serious problem unless they occur in the vocal cords or cardiac conduction tissue. Typical later joint deformities are radial deviation at the wrist (usually the earliest deformity), ulnar deviation at the MCP joints (the most characteristic deformity of RA), swan neck or boutonnière deformities of the fingers, cock-up toes, loss of arches, and hallux valgus.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Studies may assist in the differential diagnosis. RA typically produces a mild normochromic normocytic anemia and thrombocytosis but normal WBC count (unless infected or Felty syndrome is present), an ESR of 30 to 60 mm/hr, and an elevated CRP level. On plain films, RA is characteristically associated with joint space narrowing (especially in the MCP, PIP, and wrist joints), marginal bony erosions, periarticular osteopenia, and soft tissue swelling (Fig. 107.1). Joint destruction (e.g., femoral head protruding through the acetabulum) occurs late.

Fig. 107.1 Ulnar deviation in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis.

(From Harris E, editor. Kelley’s textbook of rheumatology. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2005.)

Serologic testing (RF IgM or anti–citrullinated protein antibody [ACPA]) for a new diagnosis is generally best done in the follow-up setting. False positives and negatives occur, so the results must always be interpreted in the clinical context. Although a positive RF titer (>1 : 80) develops in 85% of patients with RA in the first year of the disease, unfortunately half are negative for the first 6 months, just when early intervention is most effective. RF is frequently positive in other settings, such as subacute bacterial endocarditis and rheumatic fever, and is present in low titer in 20% of elderly patients without disease. ACPA testing is newer, becomes positive earlier, but is not as widely available as RF.16

Follow-up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

The majority of RA patients will be discharged (see Box 107.7). Immunosuppressed patients warrant high suspicion for infection and a low threshold for admission. Follow-up visits with either a primary care physician or rheumatologist (if a new diagnosis or not responding to treatment) are essential. Chronic severe joint dysfunction merits orthopedic referral for potential surgical intervention (joint replacement, arthrodesis, synovectomy).

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDS) are essential for all RA patients to prevent joint damage17,18 and are now initiated as early as possible after diagnosis (but not in the ED). The mainstay remains methotrexate, alone or in combination.19 Leflunomide (an immunomodulatory drug) and sulfasalazine are alternatives.20 Exciting new and effective biologic agents include anticytokine therapies such as etanercept, anakinra, abatacept, and rituximab.21

Osteoarthritis

Epidemiology

OA is the most common cause of joint pain and frequently leads to chronic pain and disability. In the United States, symptomatic knee OA occurs in 6% of persons older than 30 years and hip OA in 3%. About one third of adults aged 25 to 74 years have radiographic evidence of OA in at least one joint group, most commonly the hands and then the feet and knees. Prevalence increases considerably with age, and OA is a major cause of disability, lost work time, and early retirement. Before the age of 50, prevalence in most joints is higher in men, but at older ages women are more often affected in the hands, feet, and knees.22

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

On examination, disease is found to be limited to the symptomatic joints. Joint tenderness, bone enlargement, and crepitus on joint motion are common findings. Heberden nodes (hard nodules on the dorsal aspect of the DIP joints) are commonly seen in older women with OA. Malalignment is found in about half of knees with OA, typically with a varus (bowleg) deformity and often with instability on excess ROM. Joints may be mildly warm, especially if an effusion is present, but not dramatically inflamed. Late in the disease course, significant joint disability is evident (Fig. 107.2).

Treatment

Initial attempts at pain relief in the ED include analgesics, ice, and support in a position of comfort. Acetaminophen or ibuprofen may be adequate. If a patient has already adequately tried and failed to obtain relief with these medications, tramadol or narcotic analgesics should be considered. If a significant effusion is causing pain and disability, removal of fluid provides considerable relief. Intraarticular corticosteroids are also effective, especially in the knee or MCP joints, with pain relief lasting weeks to months. Intraarticular hyaluronic acid injections have been used in the knee, but their efficacy is limited.23

Follow-up, Next Steps in Care, and Admission

As with other arthritides, the vast majority of patients with OA are discharged home with recommendations for primary care follow-up, whereas those with known or strongly suspected joint infection are treated and admitted to the hospital. Several options are available for discharge analgesia.24,25 Patients with mild symptoms may need only general care measures. Acetaminophen and NSAIDs are the first-line choices. In studies both have been shown to be effective in reducing pain, although NSAIDs or celecoxib is modestly better. However, acetaminophen has less risk for side effects and thus remains a good first choice. Effective additions or alternatives include tramadol or short-term use of narcotics.

Topical NSAIDs (not salicylates) are considered core treatment of OA of the knee or hands, and topical capsaicin is considered adjunctive to core treatment of these joints; strong evidence supports their benefits.10,11 Glucosamine sulfate (1500 mg/day) and chondroitin sulfate (1200 mg/day) may shift cartilage metabolism toward a positive balance and are widely popular among patients, but the overall evidence to date shows limited efficacy26,27; these over-the-counter preparations may vary considerably in composition.

General care measures and patient education are also important (see the Patient Teaching Tips box presented earlier and Box 107.8).28 Evidence supports the benefit of exercise regimens and weight loss in patients with knee arthritis. Correction of knee malalignment with a neoprene sleeve, valgus brace, orthotics, or a combination of such devices is beneficial.29 Evidence on the benefit of acupuncture is mixed.30 Surgical interventions are useful in selected situations; knee arthroscopy is beneficial if cartilage flaps, loose bodies, or meniscal disruption is causing mechanical locking or instability. Total joint replacement for knee or hip OA often dramatically improves severe refractory pain and disability, particularly if the patient has a relatively low body mass index. Chondrocyte transplantation is an exciting intervention for future care.

Box 107.8 General Treatment Measures for Chronic Arthritis

Painful Joint

Reactive Arthritis

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Cases of reactive arthritis seen in the ED are likely to be a new diagnoses. Typically, the patient reports one or a few sites of acute joint pain, often asymmetric and with sequential onset. Common sites include large joints (one or both ankles, wrists, knees) and small joints in the feet; the upper extremities may be involved later. Fever (up to 102.2° F [39° C]), constitutional symptoms (fatigue, malaise, weight loss), and mucosal problems are common findings (Box 107.9). Low back pain, back stiffness, or sacroiliitis occurs in half the patients.31 The involved joints are often inflamed. The classic triad that was formerly named Reiter syndrome includes acute peripheral arthritis (asymmetric, oligoarticular, additive), conjunctivitis (mild, usually several days before the appearance of joint pain), and nongonococcal urethritis or cervicitis (generally mild, precedes the joint pain).

Box 107.9 Classic Signs of Reactive Arthritis (Formerly Known as Reiter syndrome)

Enthesitis—periarticular, classically Achilles or plantar tendinitis

Peripheral arthritis pattern—may be a hot erythematous joint for which active infection must be ruled out; often asymmetric oligoarthritis

Conjunctivitis—bilateral or unilateral, usually painful

Circinate balanitis on the shaft or glans of the penis; vulvitis in women—ranging from vesicles to ulcerations

Keratoderma blenorrhagicum—painless papulosquamous rash on the palms and soles, similar to pustular psoriasis

Treatment

Full-dose NSAIDs are the mainstay of therapy for reactive arthritis—a good response is typical.32 General care measures are also appropriate (see earlier), especially encouragement of continuing exercise. Systemic corticosteroid therapy is not generally indicated, but intraarticular glucocorticoids may help in alleviating persistently problematic joints after ruling out infection. Second-line medications for nonresponders include sulfasalazine or methotrexate. Experience with anti-TNF agents is limited but promising.

Septic Arthritis

Epidemiology

The incidence (expressed per 100,000 per year) of septic arthritis varies between 2 and 5 in the general population, 5 and 12 in children, 28 and 38 in patients with RA, and 40 and 68 in patients with joint prostheses. Males are usually affected more commonly than females, although with underlying RA, females are affected more often. About 10% of patients with acutely painful joints will have septic arthritis.1

The organisms causing bacterial arthritis depend on the epidemiologic circumstances (Table 107.4). For example, monarthritis of a prosthetic joint is probably due to Staphylococcus species, whereas a migratory arthritis in a sexually active woman is probably due to disseminated gonococcal infection. Rarely, the cause may be fungal, protozoal, or mycobacterial, particularly in immunosuppressed patients. Viral joint infections are not considered part of the “septic” category.

Table 107.4 Most Common Organisms and Suggested Antibiotics for Various Patient Groups with Arthritis

| AGE/GROUP | MOST COMMON ORGANISMS | SUGGESTED EMPIRIC ANTIBIOTICS |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | Staphylococcus aureus most common; also streptococci, gram-negative organisms, anaerobes, Neisseria gonorrhoeae | At risk for STD—ceftriaxone; not at risk for STD—oxacillin/nafcillin + ceftriaxone |

| Infants (<6 mo) | Escherichia coli, group B streptococci | Oxacillin/nafcillin + cefotaxime/ceftriaxone |

| Children 6-24 mo | Staphylococci, Kingella kingae (no longer Haemophilus influenzae) | Oxacillin/nafcillin + cefotaxime/ceftriaxone |

| Pediatric (>24 mo) | N. gonorrhoeae, pneumococci | Oxacillin/nafcillin + cefotaxime/ceftriaxone |

| Intravenous drug abusers | S. aureus, gram-negative organisms | Oxacillin/nafcillin + ceftriaxone |

| Prosthetic joint | MSSA/MRSA, MSSE/MRSE, Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas | Vancomycin + ciprofloxacin |

MSSA/MRSA, Methicillin-sensitive/resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSE/MRSE, methicillin-sensitive/resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis; STD, sexually transmitted disease.

Major risk factors for septic arthritis in adults include age older than 80 years, diabetes mellitus, RA, prosthetic joint or recent joint surgery, skin infection or ulceration, alcoholism, intravenous drug use, and prior intraarticular corticosteroid injection.1 Previous joint damage from any cause also appears to increase risk.

Pathophysiology

Bacteria can infect the joint via hematogenous spread, direct inoculation (arthrocentesis, trauma, surgery), or contiguous contact (cellulitis, bursitis, tenosynovitis). Any microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and protozoa, may invade joints; however, the overwhelming majority of cases (90%) are caused by the pyogenic bacteria Staphylococcus and Streptococcus.33 Once the pathogen penetrates the joint space, it initiates a series of inflammatory reactions that may lead to joint destruction and permanent damage. Microorganisms or their products (or both) activate the release of proinflammatory cytokines, such TNF-α and interleukin-1, and proteolytic enzymes, such as metalloproteinases and other collagen-degrading enzymes. These proteins induce synovial membrane proliferation, granulation tissue, neovascularization, and infiltration by polymorphonuclear cells and may result, if untreated, in cartilage and bone destruction. The articular damage may progress even after eradication of microorganisms because persistence of bacterial antigens and metalloproteinases within the joint will continue to promote an inflammatory response.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The differential diagnosis for septic arthritis is focused on other inflammatory diagnoses.39 Although low-grade fever is common with many types of inflammatory arthritis, higher fevers are more commonly associated with a septic joint, and the physician must rule out a septic joint with joint fluid analysis (see Table 107.2).

Unfortunately, laboratory tests, including synovial fluid analysis, do not diagnose or rule out septic arthritis with accuracy. Therefore, if suspicion for septic arthritis is high in the setting of negative testing, the emergency physician should not hesitate to treat for infection while awaiting the results of bacterial culture.35 Imaging studies are indicated when trauma, bone infection, malignancy, or a foreign body is suspected and are recommended before arthrocentesis. Ultrasonography may assist in identification of joint effusion.

Treatment

Pain management should be initiated early. After appropriate material for culture is obtained, parenteral antibiotics should be selected to treat the most likely pathogens (see Table 107.4). Another reasonable approach is to treat according to Gram stain results (for gram-positive cocci, start vancomycin; for gram-negative organisms, start ceftriaxone or cefotaxime). If the Gram stain is negative, vancomycin is reasonable for an immunocompetent host and vancomycin plus ceftriaxone (or cefotaxime) for an immunosuppressed individual, injection drug user, or traumatic bacterial arthritis.

Gout and Pseudogout

Pathophysiology

Calcium-containing crystals in the pericellular matrix of cartilage are often deposited in the form of CPPD and therefore lead to a disorder termed chondrocalcinosis, pyrophosphate arthropathy, CPPD crystal deposition disease, or when associated with acute arthritis, pseudogout.36 Precipitation of CPPD crystals in connective tissue is most often asymptomatic. Acute attacks are generally self-limited and often triggered by trauma, surgery, or severe medical illness.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Acute inflammatory joint pain, swelling, erythema, and tenderness with painful limited ROM are typical. Inflammatory signs often extend beyond the involved joint and resemble cellulitis. Classically, acute gout affects the first MTP joint, but more than 50% of pseudogout attacks affect the knee. Eighty percent of first gouty attacks are monarticular. Low-grade fever is common in both diagnoses, and a previous history of the joint disease is common.37

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

A known history of gout, typical precipitants, or location in the great toe suggests gout. Chondrocalcinosis (radiographic evidence of calcification in hyaline cartilage, fibrocartilage, or both) is common in pseudogout; though highly suggestive of the diagnosis, it is neither absolutely specific nor universal. Leukocytosis with a left shift and an elevated ESR may be present but are more common in pseudogout than gout. An elevated uric acid level may or may not be found in acute gout and is nondiagnostic by itself. Normal to low levels are reported in 12% to 43% of patients with acute gout attacks.38,39 The pattern of symptoms in chronic pseudogout is often similar to OA and may sometimes mimic RA. A significant minority of patients have coexisting arthritides.

Evaluation for septic arthritis is the diagnostic priority in the ED. Joint aspiration with evaluation of synovial fluid for acute inflammation, crystals, or evidence of infection is necessary, and fluid must be sent for Gram stain and culture. Urate crystals inside neutrophils diagnose gout; phagocytosed CPPD crystals are seen in pseudogout. Some patients have concurrent gout and pseudogout, with both types of crystals being found. Coexistence of crystalline and infectious arthritis in the same joint is well reported. If joint fluid analysis cannot be done, a clinical diagnosis may be made from historical and clinical data,40 but specificity is reduced (Table 107.5).

See Table 107.5, Clinical Diagnostic Rule for Acute Monarticular Gout, online at www.expertconsult.com

Table 107.5 Clinical Diagnostic Rule for Acute Monarticular Gout (Without Synovial Fluid Analysis)

| Male sex | 2 points |

| Previous patient-reported arthritis attack | 2 points |

| Onset within 1 day | 0.5 point |

| Joint redness | 1 point |

| First metatarsophalangeal joint involvement | 2.5 points |

| Hypertension or at least 1 cardiovascular disease | 1.5 points |

| Serum uric acid level > 5.88 mg/dL | 3.5 points |

| Interpretation of total: | |

| High probability of gout | ≥8 points |

| Intermediate probability | 4-8 points |

| Low probability | <4 points |

From Janssens HT, Fransen J, et al. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1120.

Treatment

Although acute attacks will resolve spontaneously, antiinflammatory medications are essential for more rapid relief of pain. Even though colchicine has traditionally been used for the acute treatment of gout, rheumatologists prefer NSAIDs (other than aspirin), oral prednisone (30 to 50 mg/day for 5 to 7 days), or intraarticular corticosteroids. Low-dose oral colchicine (1.2 mg and then 0.6 mg in 1 hour or 0.5 mg every 8 hours for 1 day) is safe and effective and avoids the diarrhea and vomiting that were common with higher-dose regimens.41,42 Pseudogout is treated with NSAIDs or intraarticular cortisone (or both); effective prevention is often achieved with low-dose colchicines or NSAIDs.

Follow-up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

Drugs that lower uric acid production (e.g., allopurinol, febuxostat) or enhance excretion (e.g., probenecid) may be used as preventive therapy but can be started at follow-up visits.43 Adjunctive measures include a diet low in uric acid (decreased meat and seafood) plus lifestyle modification. Unless an infected joint is suspected, these patients are discharged home with primary care follow-up.

![]() Documentation

Documentation

Arthritis

Presence or absence of the following:

Clearly identify the specific anatomic sites of tenderness, swelling, and erythema

PQRST, Palliation/aggravation, quality, radiation, severity, and timing.

A discussion of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, juvenile idiopathic (rheumatoid) arthritis, and psoriatic arthritis can be found online at www.expertconsult.com

Carter JD, Hudson AP. Reactive arthritis: clinical aspects and medical management. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2009;35:21–44.

Lavelle ED, Lavelle L. Intra-articular injections. Med Clin North Am. 2007;91:241–250.

Margaretten ME, Kohlwes J, Moore D, et al. Does this adult patient have septic arthritis? JAMA. 2007;297:1478–1488.

Rott K, Agudelo C. Gout. JAMA. 2003;289:2857–2860.

Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:762–784.

Salzman BE, Nevin JE, Newman JH. A primary care approach to the use and interpretation of common rheumatologic tests. Clin Fam Pract. 2005;7:335–358.

1 Margaretten ME, Kohlwes J, Moore D, et al. Does this adult patient have septic arthritis? JAMA. 2007;297:1478–1488.

2 Salzman BE, Nevin JE, Newman JH. A primary care approach to the use and interpretation of common rheumatologic tests. Clin Fam Pract. 2005;7:335–358.

3 Beachley MC, Franklin JW, Ostlund W, et al. Radiology of arthritis. Prim Care. 1993;20:771–794.

4 Chen LX, Schumacher HR. Current trends in crystal identification. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2006;18:171–173.

5 Shmerling RH, Delbanco TL, Tosteson AN, et al. Synovial fluid tests. What should be ordered? JAMA. 1990;264:1009–1014.

6 Li SF, Henderson J, Dickman E, et al. Laboratory tests in adults with monoarticular arthritis: can they rule out a septic joint? Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:276–280.

7 Sox HC, Liang MH. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate: guidelines for rational use. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:515–523.

8 Carek PJ, Hunter MH. Joint and soft tissue injections in primary care. Clin Fam Pract. 2005;7:359–378.

9 Lavelle ED, Lavelle L. Intra-articular injections. Med Clin North Am. 2007;91:241–250.

10 Moore RA, Derry S, McQuay HJ. Topical agents in the treatment of rheumatic pain. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2008;34:415–432.

11 McCleane G. Topical analgesics. Med Clin North Am. 2007;91:125–139.

12 Macedo AM, Oakley SP, Panayi GS, et al. Functional and work outcomes improve in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who receive targeted comprehensive occupational therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:1522–1530.

13 Huizinga TWJ, Pincus T. In the clinic. Rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Intern Med. 2010;6:ITC1–1-16.

14 Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, et al. 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1580–1588.

15 Combe B, Landewe, Lukas C, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of early arthritis: report of a task force of the European Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:34–45.

16 Pincus T, Sokka T. Laboratory tests to assess patients with rheumatoid arthritis: advantages and limitations. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2009;35:731–734.

17 Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:762–784.

18 Smolen JS, Landewe R, Breedveld FC, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:964–975.

19 Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, DeVries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF, et al. Comparison of treatment strategies in early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:406–415.

20 Gaujoux-Viala C, Smolen JS, Landewé R, et al. Current evidence for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: a systematic literature review informing the EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1004–1009.

21 Nam JL, Winthrop KL, van Vollenhoven RF, et al. Current evidence for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: a systematic literature review informing the EULAR recommendations for the management of RA. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:976–986.

22 Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Dieppe PA, et al. Osteoarthritis: new insights. Part 1: the disease and its risk factors. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:635–646.

23 Felson DT. Clinical practice: osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med. 2006;136:896–907.

24 Dieppe P, Brandt KD. What is important in treating osteoarthritis? Whom should we treat and how should we treat them? Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2003;29:687–716.

25 Hunter DJ, Lo GH. The management of ostearthritis: an overview and call to appropriate conservative treatment. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93:114–130.

26 Miller KL, Clegg DO. Glucosamine and chondroitin sulphate. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2011;37:103–118.

27 Clegg DO, Reda DJ, Harris CL, et al. Glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and the two in combination for painful knee osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:795–808.

28 Glass GG. Osteoarthritis. Clin Fam Pract. 2005;7:161–179.

29 Gross KD, Hillstrom H. Knee osteoarthritis: primary care using non-invasive devices and biomechanical principles. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93:131–150.

30 Ernst E. Complementary treatments in rheumatic diseases. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2008;34:455–467.

31 Khan MA. Update on spondyloarthropathies. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:896–907.

32 Carter JD, Hudson AP. Reactive arthritis: clinical aspects and medical management. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2009;35:21–44.

33 Ho G, Jue SJ, Cook PP. Arthritis caused by bacteria and their components. In: Harris ED, Jr., Budd RC, Genovese MC, et al. Kelley’s textbook of rheumatology. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2005.

34 Coakley G, Mathews C, Field M, et al. for the British Society for Rheumatology Standards; Guidelines and Audit Working Group. BSR & BHPR, BOA, RCGP and BSAC guidelines for management of the hot swollen joint in adults. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006;45:1039–1041.

35 Mathews CJ, Coakley G. Septic arthritis: current diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2008;20:457–462.

36 Rosenthal AK. Pseudogout: presentation, natural history, and associated conditions. In: Wortmann RL, Schmacher HR, Jr., Becker MA, et al. Crystal-induced arthropathies: gout, pseudogout and apatite-associated syndromes. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2006:99.

37 Rott K, Agudelo C. Gout. JAMA. 2003;289:2857–2860.

38 Park YB, Park YS, Lee SC, et al. Clinical analysis of gouty patients with normouricemia at diagnosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:90–92.

39 Schlesinger N, Norquist JM, Watson DJ. Serum urate during acute gout. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:1287–1289.

40 Jansenns HJ, Fransen J, van de Lisdonk EH, et al. A diagnostic rule for acute gouty arthritis in primary care without joint fluid analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1120–1126.

41 Zhang W, Doherty M, Bardin T, et al. for the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies, Including Therapeutics. European League Against Rheumatism evidence based recommendations for gout. Part II: management. Report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies, Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1312–1324.

42 Terkletaub RA, Furst DE, Bennett K, et al. High versus low dosing of oral colchicine for early acute gout flare: twenty-four-hour outcome of the first multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, dose-comparison study. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1060–1068.

43 Laine C, Turner BJ, Williams S, et al. In the clinic: gout. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:ITC2–1-16.

44 Gladman D. Psoriatic arthritis. In: Harris E, ed. Kelley’s textbook of rheumatology. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2005:1155.

45 Warren R, Wilking A, Perez M, et al. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JRA. In: Koopman W, Boulware D, Heudebert G. Clinical primer of rheumatology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:116.

46 Weiss JE, Ilowite NT. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2007;33:441–470.

47 Royal Australian College of General Practitioners JIA Working Group. Clinical guideline for the diagnosis and management of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, 2009. pp. 1–39.

48 Anthony K, Schanberg L. Pediatric pain syndromes and management of pain in children and adolescents with rheumatic disease. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005;52:611–639.

49 Leung A, Lemay J. The limping child. J Pediatr Health Care. 2004;18:219–223.

50 Joseph B, Varghese G, Mulpuri K, et al. Natural evolution of Perthes disease. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23:590–600.

Psoriatic Arthritis

Pathophysiology

Onset is usually insidious, though sometimes abrupt. Trauma to a joint may precipitate a flare at that site. Several patterns of joint involvement occur, most commonly an asymmetric oligoarthritis similar to reactive arthritis or a symmetric polyarthritis similar to RA. Spondylitis may be prominent. Most patients with PsA do very well, with severe and progressive disease developing in less than 25%. A rare subtype includes pustular acne and osteomyelitis. HIV-infected patients manifest a more severe and destructive form of PsA.44

Juvenile Idiopathic (Rheumatoid) Arthritis

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

• Rash—evanescent, salmon-colored macules, often seen with a daily fever spike

• Serositis—pericarditis in more than one third, but tamponade is rare

Additional subtypes include enthesitis-related arthritis (4 : 1 male preponderance, usually age >8, often HLA-B27 positive, spinal involvement) and PsA (pauciarticular, skin psoriasis or family history, nail changes, dactylitis), which often precedes any skin lesions by years. Other children demonstrate overlap patterns.45

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Other rheumatologic possibilities include systemic lupus erythematosus, juvenile dermatomyositis, autoimmune hepatitis, sarcoidosis, and drug reactions. Joint pain occurs with hemoglobinopathies, hemophilias, and leukemias. Localized pain may be traumatic. Diffuse musculoskeletal pain and systemic symptoms (not fever) occur with childhood fibromyalgia.46

Legg-Calvé-Perthes Disease

Pathophysiology

The cause of LCP disease and its inciting factors remain unknown. Disruption of vascular flow (perhaps by a cartilage disorder) to the capital femoral epiphysis causes small episodes of infarction that lead to osteochondrosis and potential collapse of the epiphysis. Later revascularization allows reabsorption and replacement with new bone and cartilage, usually with complete healing over a period of 3 to 4 years. Residual deformity may result in disability or severe OA years later. The process is generally unilateral, but 10% have bilateral involvement, and effusions may be present.47

Differential Diagnosis

Several other entities may cause hip problems and limping,48,49 and distinction may not be possible in a single ED visit. Constitutional symptoms, fever, and associated disorders are not part of LCP disease. Radiographs are often tremendously helpful in making the diagnosis, as is nuclear scintigraphy. Septic arthritis or osteomyelitis must always be considered, especially with systemic symptoms or another site of infection. Severe pain, acute onset, ESR higher than 20 mm/hr, or temperature above 37.5° C suggests a septic hip. Transient synovitis of the hip is the most common cause of hip pain, with age at peak onset similar to that for LCP disease, but it usually resolves within a month; about half are initially seen in an acute stage, unlike LCP disease. Persistent synovitis may follow a course consistent with LCP disease. Other inflammatory diseases (JRA, rheumatic fever) usually have other joint involvement or systemic findings (or both). Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) tends to occur at older ages (12 to 16 in boys, 10 to 14 in girls). Those with stable SCFE have an intermittent limp and pain with a chronic onset, whereas unstable SCFE is often manifested acutely after a twisting injury. The diagnosis of SCFE is usually made with plain films, although CT or MRI is sometimes needed.

Treatment and Disposition

Mild analgesics may be used as needed. Further treatment of LCP disease is done in the outpatient setting, with orthopedic consultation. “Containment” refers to reducing the pressure force on the hip by varus repositioning, with the goals of keeping the femoral head contained in the acetabulum, assisting blood flow, and molding its shape on remodeling. This is usually achieved by braces, but operative intervention may be required. Occasionally, temporary periods of rest are needed.50