Jaundice (Case 25)

Austin Hwang MD and Giancarlo Mercogliano MD, MBA, AGA

Case: A 60-year-old man presents with jaundice, 20-pound weight loss, intermittent nausea, and decreased appetite over the last month. He has a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes. There is no past surgical history. He takes hydrochlorothiazide, simvastatin, and metformin. His BP, cholesterol, and diabetes are under good control. He has drunk three beers each day and smoked half a pack of cigarettes per day for the last 40 years. He has no abdominal pain, but he has noticed that his stools have become lighter in color and his urine has become tea-colored. He presents in the outpatient office accompanied by his wife and three of his children, who have urged him to seek medical attention.

Differential Diagnosis

|

Hepatocellular Causes |

Extrahepatic/Obstructive Causes |

|

Viral hepatitis |

Choledocholithiasis |

|

Alcoholic hepatitis |

Cholangitis |

|

Drug-induced hepatitis |

Benign stricture |

|

Cirrhosis |

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma |

Speaking Intelligently

When asked to see an older patient with jaundice, we worry about cancer. A helpful start in patients with this clinical presentation is to decide whether the cause is hepatocellular or obstructive. These two categories serve as a useful framework to think about elevated serum bilirubin levels. Treatment of hepatocellular causes is generally supportive, while treatment of obstructive causes is with endoscopy or surgery. History taking allows me to create a diagnostic hypothesis. Laboratory values and imaging help me to corroborate this hypothesis. Liver function tests (LFTs) are crucial. Ultrasonography evaluates the hepatic parenchyma and biliary ducts.

PATIENT CARE

Clinical Thinking

• Use LFTs and imaging (ultrasound, CT, MRI) to help corroborate your hypothesis.

• Pattern recognition of LFTs aids in diagnosis. Please see below.

History

• History of associated pain or lack of pain is important.

• Past medical history is important: History of gallstones (choledocholithiasis), colon cancer (liver metastases), or chronic pancreatitis (bile duct strictures).

Physical Examination

• In the presence of fever, think cholangitis.

Tests for Consideration

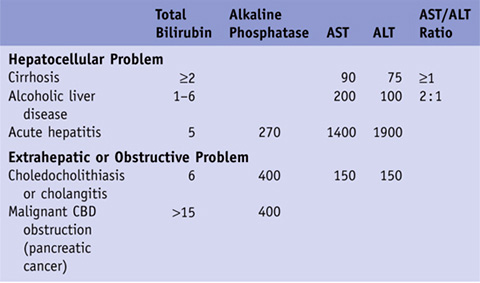

Table 32-1 Typical Laboratory Values*

*For clarity, we have chosen typical values that are representative of each condition. Those fields that are empty are either too variable to quantify or not useful as diagnostic guides.

CBD, common bile duct.

| Clinical Entities | Medical Knowledge |

|

Hepatitis |

|

|

Pφ |

Inflammation of the liver with many etiologies including alcohol, herbal drugs, medications, infection (hepatitis A/B/C/E, Epstein-Barr virus [EBV], and cytomegalovirus [CMV]). |

|

TP |

Patients present with right upper quadrant pain and significant elevations in AST and ALT. The alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin can also be elevated, but usually not as high as the AST and ALT values. Patient will complain of “flulike” symptoms such as malaise, nausea, weakness, decreased appetite, decreased oral intake, fever, night sweats, and chills. |

|

Diagnosis is often made by careful history. Ask about alcohol use, recent travel, new medications, herbal medications, recent sick contacts, acetaminophen usage, and high-risk sexual activity. If a viral etiology is suspected, blood sample should be sent for hepatitis A IgM, hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B core IgM antibody, hepatitis e antigen, hepatitis C RNA, and CMV and EBV serology. Acetaminophen levels are checked if there is suspicion of acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. Abdominal ultrasound will show an enlarged liver, and physical exam may reveal hepatomegaly. |

|

|

Tx |

If the source is viral, the treatment is usually supportive care. Most patients recover rather quickly with no remaining sequelae of disease. If hepatitis B or C is the etiology, some of these patients may go on to have chronic liver disease. If acetaminophen toxicity is the etiology, treatment can be initiated with N-acetylcysteine. Herbal drugs, alcohol, and inciting medications should all be stopped. If alcohol is thought to be the culprit, be wary of signs of alcohol withdrawal. See Cecil Essentials 43. |

|

Cirrhosis |

|

|

Pφ |

Long-standing liver disease secondary to either previous or ongoing insults (hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or alcohol) or a primary disease (autoimmune hepatitis, hemochromatosis, Wilson disease, amyloidosis, α1-antitrypsin deficiency, primary biliary cirrhosis [PBC], primary sclerosing cholangitis [PSC]). Hepatitis B is the most common cause worldwide. Hepatitis C and alcohol are the most common causes of cirrhosis in the western world. |

|

TP |

Patients with cirrhosis often do not realize they have the disease until they present with sequelae, such as ascites, encephalopathy, hematemesis, or pruritus. These patients are susceptible to infections (pneumonia, bacteremia, and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis) and deep venous thrombosis. |

|

Dx |

The AST/ALT ratio and total bilirubin can be either normal or elevated. Imaging with abdominal ultrasound, CT, or MRI will demonstrate a nodular liver contour with a coarse echotexture. Because of the prolonged inflammation and resulting fibrosis, the liver is often small and scarred, unlike the picture of acute hepatitis described above. Liver biopsy establishes the definitive diagnosis of cirrhosis. |

|

Treatment depends on the cause of cirrhosis. Clearance of the hepatitis B virus can be attempted with pegylated interferon, lamivudine, adefovir, or entecavir. Clearance of the hepatitis C virus can be attempted with combination therapy of pegylated interferon + ribavirin; the addition of a protease inhibitor (e.g., teleprevir or boceprivir) to standard therapy has been shown to increase response rates and improve outcome. Despite these attempts, clearance of the virus does not reverse the patient’s cirrhosis. Stop alcohol intake. Steroids aid in treatment of autoimmune hepatitis. Phlebotomy and deferoxamine have been used for hemochromatosis. Penicillamine has been used for Wilson disease. Ursodiol has been used to slow down the progression of PBC and PSC. Encourage a low-sodium diet. If the patient is retaining fluid in the abdomen or legs, a course of diuretics can be attempted as long as the kidney function is intact. Upper endoscopy is needed in cirrhotics to rule out esophageal and gastric varices. If encephalopathy is present, rifaximin and lactulose have been crucial in improving patients’ mental status. Ultimate treatment would be liver transplantation. See Cecil Essentials 45. |

|

|

Choledocholithiasis |

|

|

Pφ |

Choledocholithiasis is the presence of gallstones in the bile ducts. The gallstones originate from the gallbladder. Occasionally, stones may form in the bile ducts de novo, but this is difficult to prove unless the gallbladder has been removed for more than 1–2 years. Bile duct stones found less than 2 years from a previous cholecystectomy are referred to as “retained” stones. |

|

TP |

Patients present with RUQ abdominal pain and jaundice. Intermittent obstruction can occur several times before medical help is sought. |

|

Dx |

LFTs demonstrate an obstructive pattern. Ultrasound will often show dilated biliary ducts proximal to the obstruction. |

|

Tx |

The treatment depends on local expertise. Most centers perform a laparoscopic cholecystectomy with a pre- or postoperative ERCP. During the ERCP, stones are extracted with balloon dilatation and sphincterotomy. Another approach is cholecystectomy with bile duct exploration. This can be performed with good results, and it may be preferred by some patients as it requires only a single procedure. See Cecil Essentials 46. |

|

Pφ |

Cholangitis is usually preceded by choledocholithiasis. Stasis creates a medium for exponential bacterial growth, inflammation of the ducts, and ultimate infection. |

|

TP |

Patients with cholangitis may appear ill and present acutely with nausea/vomiting, fevers, night sweats, and chills. Decreased oral intake, abdominal pain, weakness, and malaise are common findings. Two eponyms have been associated with cholangitis: Charcot triad (fever, abdominal pain, and jaundice) and Reynold pentad (fever, abdominal pain, jaundice, septic shock, and mental status changes). |

|

Dx |

Bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase are typically more elevated than AST and ALT because of the location of the pathology. Leukocytosis is often present on CBC. Abdominal ultrasound shows dilated biliary ducts and can sometimes localize the area of obstruction. MRCP or EUS can localize the area of obstruction. ERCP is a diagnostic and therapeutic procedure that is the gold standard for biliary obstruction. |

|

Tx |

Initially, these patients should be kept on a regimen of nothing by mouth, given IV fluids, and treated with IV antibiotics primarily directed toward anaerobes and gram-negative bacilli. ERCP allows removal of the obstructing gallstone and debris, and decompression of the biliary tree. If the biliary obstruction is too high up in the biliary tree or the patient has had previous surgical procedures that make ERCP difficult, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) can be helpful in decompressing the bile ducts. See Cecil Essentials 46. |

|

Benign Stricture |

|

|

Pφ |

Benign stricture refers to partial obstruction of the biliary tract not due to stones or malignancy. Approach all strictures as if you suspect malignancy. Diseases that can cause strictures include sclerosing cholangitis, previous episodes of pancreatitis, parasites, or previous cholangitis episodes. After cholecystectomy, biliary duct injury (partial transection or cautery burn) can also cause strictures. |

|

TP |

Patients present with intermittent or progressive jaundice with occasional pain. Alkaline phosphatase is usually elevated. |

|

Dx |

Abdominal ultrasound is generally the first imaging test, but strictures will be better seen on CT or ERCP/MRCP. The latter two studies will allow for better delineation of the anatomy. |

|

Benign strictures require an exhaustive search for a cause. Via ERCP, the stricture can be stented and biopsy specimens and brushings of the stricture can be obtained. If malignancy can’t be excluded, a “blind Whipple” procedure may be necessary. See Cecil Essentials 46. |

|

|

Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma |

|

|

Pφ |

Risk factors for pancreatic cancer: age > 60 years, male sex, smoking, diets high in red meat, diets low in vegetables and fruit, obesity, diabetes, family history of pancreatic cancer, Helicobacter pylori infection, and chronic pancreatitis. |

|

TP |

Clinical presentation consists of nonspecific symptoms such as nausea, malaise, decreased appetite, decreased oral intake, and weakness. Weight loss is common. Patients may also note tea-colored urine, pale-colored stools, and diarrhea/steatorrhea. Abdominal pain starts in the epigastric region and radiates to the back, but some patients don’t have pain at all and present with “painless jaundice.” Development of diabetes may be an early sign of pancreatic cancer. Trousseau sign—migratory thrombophlebitis. Courvoisier sign—porcelain gallbladder. |

|

Dx |

AST, ALT, bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase will all be elevated. Imaging with abdominal ultrasound, CT of abdomen/pelvis, or MRI helps to visualize the mass. As with any cancer, it is crucial to have a tissue diagnosis to confirm disease. EUS gives a very good view of the pancreas, and one can obtain biopsy samples of the pancreatic mass or any surrounding abnormal lymph nodes. An elevated serum CA 19-9 has a 77% sensitivity and an 87% specificity for malignant disease. |

|

Tx |

If the cancer is localized, a Whipple procedure (pancreaticoduodenectomy) can be done. If the cancer has spread, chemotherapy and radiation are used for treatment. Gemcitabine, oxaliplatin, and erlotinib (Tarceva) are a few of the chemotherapeutic drugs used. Median survival from diagnosis is 3–6 months, and 5-year survival is less than 10%. See Cecil Essentials 40, 57. |

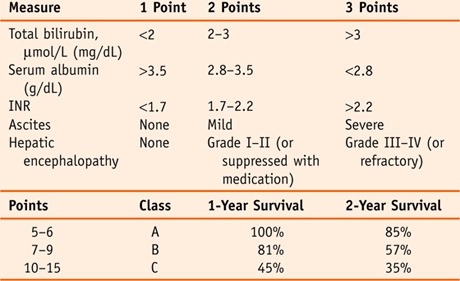

Practice-Based Learning and Improvement: Evidence-Based Medicine

Title

Transection of the esophagus for bleeding esophageal varices. Prognostic value of Child-Turcotte criteria in medically treated cirrhotics

Authors

Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, et al.

Reference

Br J Surg 1973;60:646

Problem

Predicting outcome in cirrhotic patients

Outcome/effect

In 1964, Child and Turcotte proposed a scoring system based on five criteria in an effort to classify the severity of liver disease in cirrhotic patients. Nine years later, Pugh et al. modified the scoring system by replacing nutritional status with PT/INR, thus removing one of the most subjective parts of the score. It was originally created to predict mortality during surgery, but it can also be used to determine necessity for liver transplantation.

Interpersonal and Communication Skills

Give Forethought to the Setting When Delivering Bad News

With a serious medical illness such as unresectable pancreatic cancer, there are times when patients will have little chance for meaningful recovery. In communicating a poor prognosis or bad news in general, it is often helpful to set up a family conference.

Before a family meeting occurs, here are some tips for basic planning:

Have your facts straight before you begin.

Have your facts straight before you begin.

Choose a setting that is private where everyone can sit down.

Choose a setting that is private where everyone can sit down.

Be sure that tissues are available.

Be sure that tissues are available.

Avoid carrying on such conversations at the bedside or in a busy hallway.

Avoid carrying on such conversations at the bedside or in a busy hallway.

Professionalism

Maintain Patient Confidentiality

As a physician, your responsibility is to the patient. There will be times when you walk into a patient’s room expecting to convey the results of a test, and the room is filled with family and friends. Resist any temptation to deliver the information; it would be essential to ask privately if the patient feels comfortable with the others in the room hearing the information. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996, effective April 2003, addresses the security and privacy of health data. HIPAA has resulted in health professionals and hospitals being more vigilant in protecting patient data from those not involved in the patient’s care. Specific tips for students and resident house staff include:

Do not discuss cases in public areas (elevators, hallways, cafeterias).

Do not discuss cases in public areas (elevators, hallways, cafeterias).

Do not leave computerized patient lists in areas shared by patients and their families.

Do not leave computerized patient lists in areas shared by patients and their families.

Respond courteously and appropriately to persons asking for information.

Respond courteously and appropriately to persons asking for information.

Procedures may be necessary in cholestatic cases of jaundice. In pancreatic cancer, for example, placement of a biliary stent can help to relieve obstruction in the bile ducts; in cholangitis, an ERCP can remove the stone or debris causing the biliary obstruction. These and all procedures require that an informed consent is obtained before the procedure can be performed. An informed consent signifies that the physician performing the procedure has explained to the patient what the procedure entails, why it is indicated, the potential benefits, the potential risks, and the therapeutic alternatives. The informed consent is a legal necessity that gives the physician a formal opportunity to discuss each procedure fully with the patient. When a patient is determined to be incompetent to make his or her own decisions, consent must be obtained from his or her power-of-attorney designee or next of kin.

Suggested Readings

Child CG III, ed. The liver and portal hypertension. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1964.

Oullette JR, Schmidt DJ. Surgery: cases in surgical oncology, Section III, 2007.

Be cognizant of who are the legal decision makers and the influential family members; this may help you anticipate the dynamics of the upcoming conversation.

Be cognizant of who are the legal decision makers and the influential family members; this may help you anticipate the dynamics of the upcoming conversation. If possible, invite other members of the health care team, including specialists and nurses, so that information and voices are consistent.

If possible, invite other members of the health care team, including specialists and nurses, so that information and voices are consistent. Avoid a seating arrangement that may be seen as confrontational or paternalistic, where the physician is on one side of the table and the family is on the other.

Avoid a seating arrangement that may be seen as confrontational or paternalistic, where the physician is on one side of the table and the family is on the other. Make arrangements to ensure that you will not be constantly interrupted (e.g., sign out your beeper, silence your cell phone).

Make arrangements to ensure that you will not be constantly interrupted (e.g., sign out your beeper, silence your cell phone). If the family is not primarily English speaking, arrange for an official hospital interpreter to be present or utilize a language line (if available). Avoid having family members translating for other family members, as it is difficult to assess how much they understand and whether the translation is correct.

If the family is not primarily English speaking, arrange for an official hospital interpreter to be present or utilize a language line (if available). Avoid having family members translating for other family members, as it is difficult to assess how much they understand and whether the translation is correct. Do not access information on patients that are not under your care (e.g., actors, politicians, sports figures).

Do not access information on patients that are not under your care (e.g., actors, politicians, sports figures).